Reloader's Press

.45 Colt Myths Part II

column By: Dave Scovill | August, 19

I asked Pete deCoux, a neighbor, world cartridge authority and expert in such matters, the same question. Pete suggested the obvious. To paraphrase, just because no one has, or has not seen, an inside-primed case with 40 grains of black powder in a collection doesn’t mean they don’t exist.

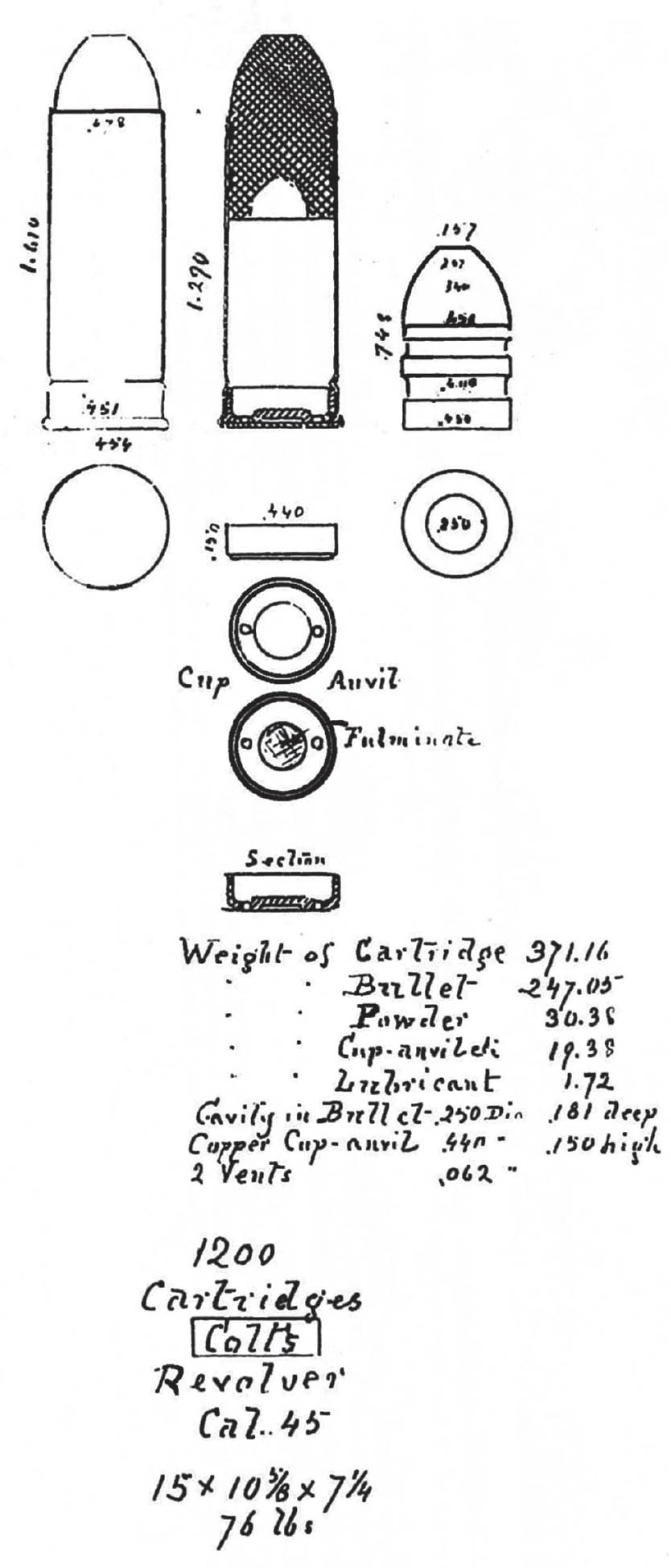

Pete rummaged through a couple of reference books and came up with drawings dated October 15, 1910, (see illustration) for the Frankford Arsenal 1873-1874 load using an inside-primed (Benét) case with a 247.05-grain conical flatnose (RNFP) lead bullet seated over 30 grains of black powder. Total weight of the cartridge was 371.16 grains. The U.S. government was using inside-primed copper cases – not outside-primed copper or brass cases – in those days, so the cartridge we are looking for would have 40 grains of powder in an inside-primed (Benét) copper case weighing 10 grains more than the

Pete had a few of those 30-grain loads, so I purloined two and weighed them at 371.3 and 369.0 grains on an RCBS electronic scale. Considering all the components that make up the total cartridge, it is interesting that the samples were so close to the total weight of all the components in the drawings – case, bullet, primer, priming compound, powder charge, anvil, etc. – using an electronic scale roughly 145 years after they were manufactured.

Based on black-powder charges dug out with a plastic pick from .45 Colt and .45-70 factory loads over the years, the 369.0-grain cartridge weight is likely within plus or minus whatever allowance, and standard deviation criterion for ammunition produced on automatic loading machines of the period. Also note the bullet weight in the sample is 247.05 grains, vice 250.

It is quite likely that the copper case, which was essentially a rimfire case with inside centerfire priming, was not suitable for holding pressures developed by a heavier powder charge. Military records from the U.S. and Canada are full of comments from officers regarding recruits’ complaints about excessive recoil of some cartridges, such as the .45-70 with 70 grains of powder and a 500-grain bullet, and large-caliber revolver loads, and help explain the changeover from the .45 Colt to the .38 Long Colt in 1892. History also suggests the standard .38 S&W Special generates about all the recoil most post-1900 law enforcement personnel don’t object to.

In his book, Moore cites a letter from General Franklin to Lt. Gen. J.G. Benton dated May 8, 1875. It reads, “After our trials at Springfield just after the adoption of the pistol, we concluded to drop the 32 grs & have considered 30 grs. powder & 250 grs. ball 9/10 lead and 1/10 tin, our standard.”

Extrapolating from C. Kenneth Moore’s research in the Colt records at the Connecticut State Library, it appears Frankford did not make .45 Colt ammunition in the 1.25-inch case after 1875 until the changeover from the .38 Long Colt to the Model 1909 .45 Colt smokeless load. This raises the question of which load Roosevelt’s Rough Riders took to Cuba in 1898.

The question is answered by a letter in Moore’s book from Colt, cautioning the government to not use smokeless loads in the refurbished black-powder-era .45 Colts that made up the majority of handguns going to Cuba. From records, it appears the majority of ammunition in the 1.25-inch case with the 250-grain bullet and 30 grains of black powder was shipped to San Antonio, Texas, for storage in 1875-76, and issued to Roosevelt’s troops in 1898 upon arrival in San Antonio, prior to shipping out for Cuba.

Apparently, some former authorities after 1890 or so assumed the “UMC,” “Rem-UMC” and “Rem.” headstamps and outside-primed brass cases with the 40-grain powder charge had been around since the inception of the .45 Colt in 1873. According to Colt records reviewed by Moore, and referring to G.G.’s query above, there is no reference to suggest Frankford Arsenal manufactured a 40-grain, .45 Colt black-powder load in a brass outside-primed case. By process of elimination, that leaves us with the 40-grain 1880 UMC load with outside priming in a brass case as the earliest known – so far.

A few readers asked why I questioned what “everybody” knew was the standard load with 40 grains of black powder in the .45 Colt cartridge in the first place. As it turns out, a Mr. Johnson, a collector of older black-powder-era rifles and handguns was employed – semi-retired – as a watchman and lived in a camping trailer onsite at Associated Plywood logging operations on weekends or during work shutdowns. As legend had it, he was armed with a Winchester Model 71 .348 WCF and an old Colt .45.

I rode my bicycle by the Johnson house on the 13-mile ride after Little League baseball practice and games, and his wife sometimes offered a glass of iced tea to fortify me for the last leg of the trip home. In the summer of 1955, while I drank tea in the Johnson’s living room, he handed me a Colt SAA .45 Colt with a 7.5-inch barrel and stated, in so many words, that the sights on those old guns weren’t any good for modern ammunition. The front sight was too short, and factory loads hit high at any reasonable distance. I assumed he was talking about those 250- or 255-grain loads that were sold in general stores in the area.

Over the years, I heard other collectors echo Mr. Johnson’s statement, except they often claimed the guns were sighted for 100 yards with 40-grain, black-powder loads and heavy bullets, which by the time I actually owned a Colt .45 with a 7.5-inch barrel in 1973, seemed about right. What I didn’t pay enough attention to was the post-World War II front sights were taller than pre-1890s sights. Either way, I let it drop, mostly because a 20-something know- nothing doesn’t ask stupid questions or challenge a collector with a dozen or so Colt SAAs on the table at a gun show.

It wasn’t until I actually measured the height of the front sight on a circa 1880 Colt .45 several years ago at approximately .25 inch tall and .5 inch front to back that I realized Mr. Johnson had it right, the front sight on black-powder military Colts were for the S&W (.45 Colt Government) load with a 230-grain bullet seated over 30 grains of powder in the 1.10-inch case that was sighted for 25 yards. Apparently, he was the only “expert” of the day who still used those guns on the job, to ward off trespassers and would-be thieves.