Learn To Reload (Handloading Basics)

Case Inspection and Preparation

feature By: John Haviland | April, 19

Peterson Cartridge uses a total of 22 different machines to make cases from start to finish, including draw presses, annealing ovens, washers and other machines to shape the brass. Three draws are required to form all of its cases. Brass is annealed a total of four times: twice during the drawing of the brass, once before the mouth of the case is tapered and once after the mouth of the case is tapered.

“Tooling for each individual caliber can look vastly different and more complicated than the rest,” he said. “For instance, the heading dies are shaped differently to form belted cartridges, and dies for drawing the brass vary depending on the size and length of the different calibers.” The size of cases also determines how fast the machines are able to run; longer cases require the brass to be drawn out slower.

Case Design

Rifle and handgun cases are formed into four basic head designs: rimmed, rimless, rebated rim and belted. The rim diameter of rimmed cases is substantially wider than the case body. These cases, like the .30-30 Winchester, have a rim to set headspace.

The rimless case name is sort of a misnomer because all cases have a rim for a gun to extract the case out of the chamber. The

Rimless cases, like the .30-06, usually have their headspace set on the shoulder. Rebated rims are narrower in diameter than the case body and include a notch in front of the rim for the extractor to engage. Belted cases are usually rimless with a belt in front of the rim about the same diameter as the rim. Headspace is normally set on the belt, but sometimes on the shoulder.

Cases are further identified as straight walled or bottleneck. Straight walled is an inexact term. The .45-70 Government is considered a straight-walled case. However, it tapers from .504 inch in front of its rim to .480 inch at its mouth. Bottleneck cases, well, look like a bottle. Their headspace may be set by a rim like the .30-30 Winchester, a belt like the .300 Winchester Magnum or a shoulder like the .30-06.

Inspection

A batch of new cases may appear ready to load. However, close examination often reveals dented and rough case mouths.

It should go without saying to make sure all cases are the same. A magnet can be used to weed out steel cases. A .250 Savage case looks similar to a 6.5 Creedmoor case, and a 6.5mm bullet easily seats in a .250 case. The resulting cartridge, though, has an extremely short headspace and would likely split when fired in a 6.5 Creedmoor chamber.

Cases with splits, cracks, torn and bent rims and corrosion should be tossed into the recycle bin. A

A narrow, bright ring around a case head is an indication of undue stretching from excessive headspace, resizing or both. Don’t mistake it for the wider mark where the sizing die stops. If in doubt, bend the tip of a paper clip and lightly pull the tip over the web section inside the case. The feel of a shallow depression indicates thinning – toss out such a case.

Headspace and Sizing

A handloader must understand headspace before sizing cases. The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) defines headspace as “The distance from the face of the closed breech of a firearm to the surface in the chamber on which the cartridge case seats.”

What headspace comes down to is clearance. Manufacturing necessitates cartridges, chambers and reloading dies vary some in dimensions. However, tolerances are minimal. Headspace for the 7mm-08 Remington cartridge is set on a point on the shoulder. That point is 1.634 inches from the face of the head of a 7mm-08 case. A 7mm-08 chamber at that point can vary from 1.630 inches minimum to 1.640 inches maximum, according to SAAMI. Say the chamber of a 7mm-08 is on the maximum side, and a sizing die is set to full-length size cases and pushes shoulders back to 1.630 inches or even shorter. That .01 inch or more doesn’t sound like much, but it is. A sizing die I once used set shoulders back .011 inch on 7mm Remington Magnum cases. Screwing the die out a partial turn would not correct that, because then the case body was not sized enough. That much sizing, then stretching on firing, resulted in cases splitting in front of the belt after they had been fired three times. A new die sets shoulders back only .003 inch, and cases last much longer.

A neck-sizing die does away with the worry of proper shoulder position because it sizes only the neck, leaving the shoulder in its fired position. A cartridge with only its neck sized will fit back in the chamber it was fired in. However, cases spring back a little less each time they are fired. After a case has been fired and its neck sized a time or two, it becomes hard to chamber and will require full-length sizing to correctly fit in a chamber.

Straight-walled handgun cases are normally full-length sized so they will drop into a revolver’s cylinder chamber or feed smoothly from the magazine into the chamber of an autoloading pistol.

Straight-walled handgun and rifle case mouths are flared slightly to ease bullet seating. The expander die in a three-die set expands the case to the proper diameter to accept the bullet, and flares the case mouth. The same goes for bottleneck cases that are loaded with lead-alloy bullets. A Lyman M-Die accomplishes this by expanding the inside of the case neck to just below bullet diameter, and slightly bells the mouth. Case mouths should be flared just enough for a bullet’s base to fit inside it. This keeps a case mouth from shaving material off the bullet heel or snagging the heel and crumpling a case when a bullet is seated. There is no sense in over-working cases with an excessive amount of flare, because it eventually causes a premature split on the mouths.

Primer Pockets

Except for an occasional bad case, primer pockets in cases are uniform in depth and width. Nevertheless, some handloaders prefer to uniformly cut pockets so primers seat exactly the same depth to receive the same amount of strike from the firing pin. They also chamfer the inside of flash holes, so the primer’s flame is unobstructed to ignite powder.

I conducted an experiment to determine if conditioning primer pockets and flash holes is worth the work. I loaded 10 plain Winchester .243 Winchester cases with 38.0 grains of VV-N140 powder and Sierra 70-grain HPBT Match bullets. The same load went in 10 other cases with their primer pockets cut with a Redding Primer Pocket Uniformer, and the inside of the flash holes were chamfered with a Redding Flash Hole Deburring Tool. At most, the tools removed a few flecks of brass from the prepared cases. The plain-case loads provided five-shot groups of .25 and .61 inch at 100 yards using a Cooper Firearms Model 22. The carefully prepared cases provided five-shot groups of .69 and .82 inch. So, there really was no significant difference in accuracy between the plain and prepared cases.

Some handloaders remove fired primer residue left in pockets and others don’t. Some handloaders think the deposits prevent primers from fully seating. Others feel such a miniscule amount is of no concern.

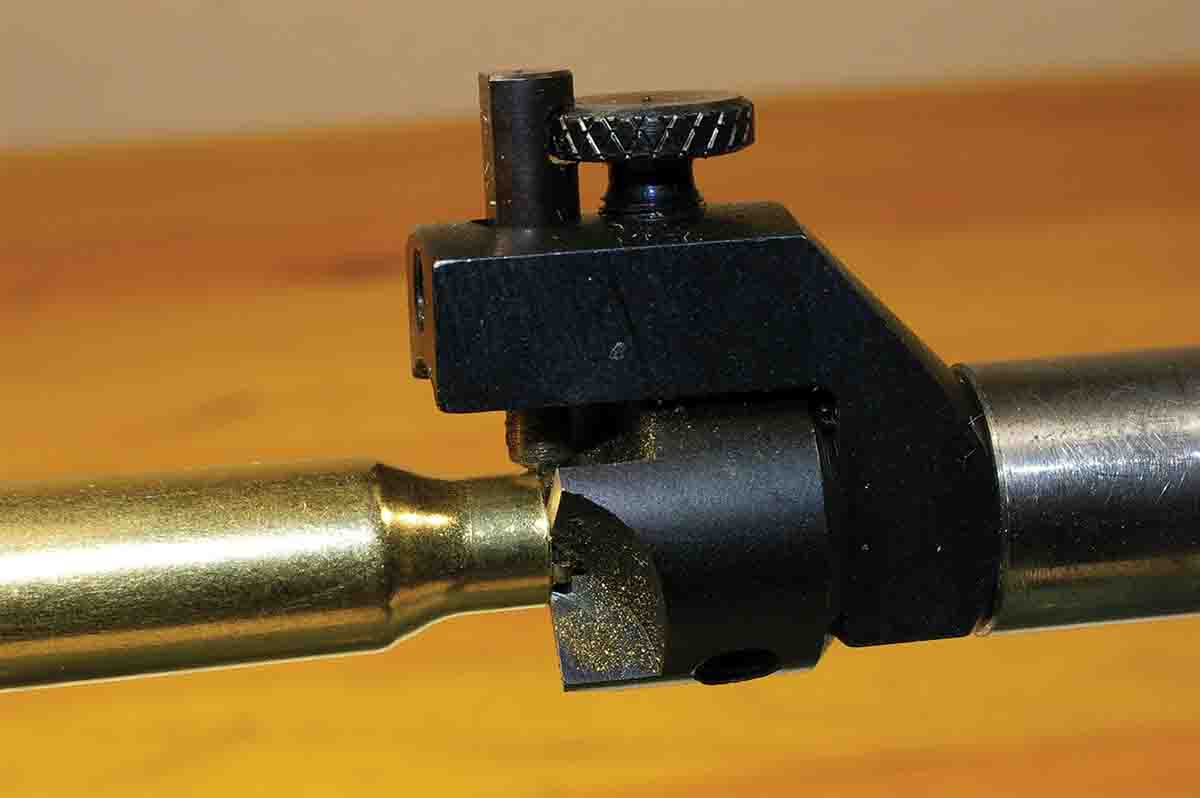

Trimming

How the burrs left from trimming brass on case mouths is removed is one factor in building an accurate load. The curl of brass on the outside must be completely

Cleaning

Although clean cases are technically unnecessary, they are a sign a handloader has taken the steps to produce top-quality cartridges. Vibrating or tumbler case cleaners use ground corncob or walnut shells to polish away fouling. The biggest problem with corncob or walnut is it gets stuck inside small-caliber cases like the .17 Hornet. Kernels plug up primer pockets and flash holes and must be picked out.

In the last few years, sonic cleaners have taken case cleaning to a new level. Sonic cleaners “scrub” the inside and outside of cases by creating high frequency vibrations that produce tiny air bubbles in the cleaning solution. The air bubbles burst on the surfaces of submerged cases to loosen dirt, powder fouling and sizing lubricant. Cleaned cases have a dull look. Cases must be rinsed and dried before moving on to the next loading step.

Case Life

Zach Aaron said case life depends on multiple factors, most notably pressure level. “Higher pressure causes the primer pocket

A while back I set out to determine how long rifle cases last. I took my reloading tools, two once-fired Remington .270 Winchester cases, a pound of H-4831 powder, a flat of primers and a box of 130-grain bullets to the range. I loaded one case with the minimum powder charge and the other with the maximum charge listed in a handloading manual. I fired each cartridge through a bolt-action Ruger M77 .270. Each case was full-length sized after it had been fired and loaded again and again. The cases were trimmed when required.

The longevity winner is a shoebox full of .30-06 cases with an “SL 43” headstamp. I fired these World War II cartridges and reloaded and fired them again several times with full-power hunting loads. In the past 30 years, I have loaded and shot them with cast bullets and Unique powder using a charge that develops about 25,000 copper units of pressure (CUP), or nearly half that of full-power loads. They have been fired about 30 times and are still going strong.

Preparing and keeping those cases in suitable condition took only a short while each time they were reloaded. Consider that time an investment in safety, quality handloads and saving money.