New Brass

Improved Consistency and Concentricity

feature By: John Barsness | April, 19

Other brands eventually came and went, including Federal, which is again in the component brass market. Most handloaders stuck with Federal, Norma, Remington and Winchester brass, though Norma’s brass often came headstamped with another name.

Fast-forward, and in 2019 we can buy so many new brands of American-made brass (along with several established foreign brands)

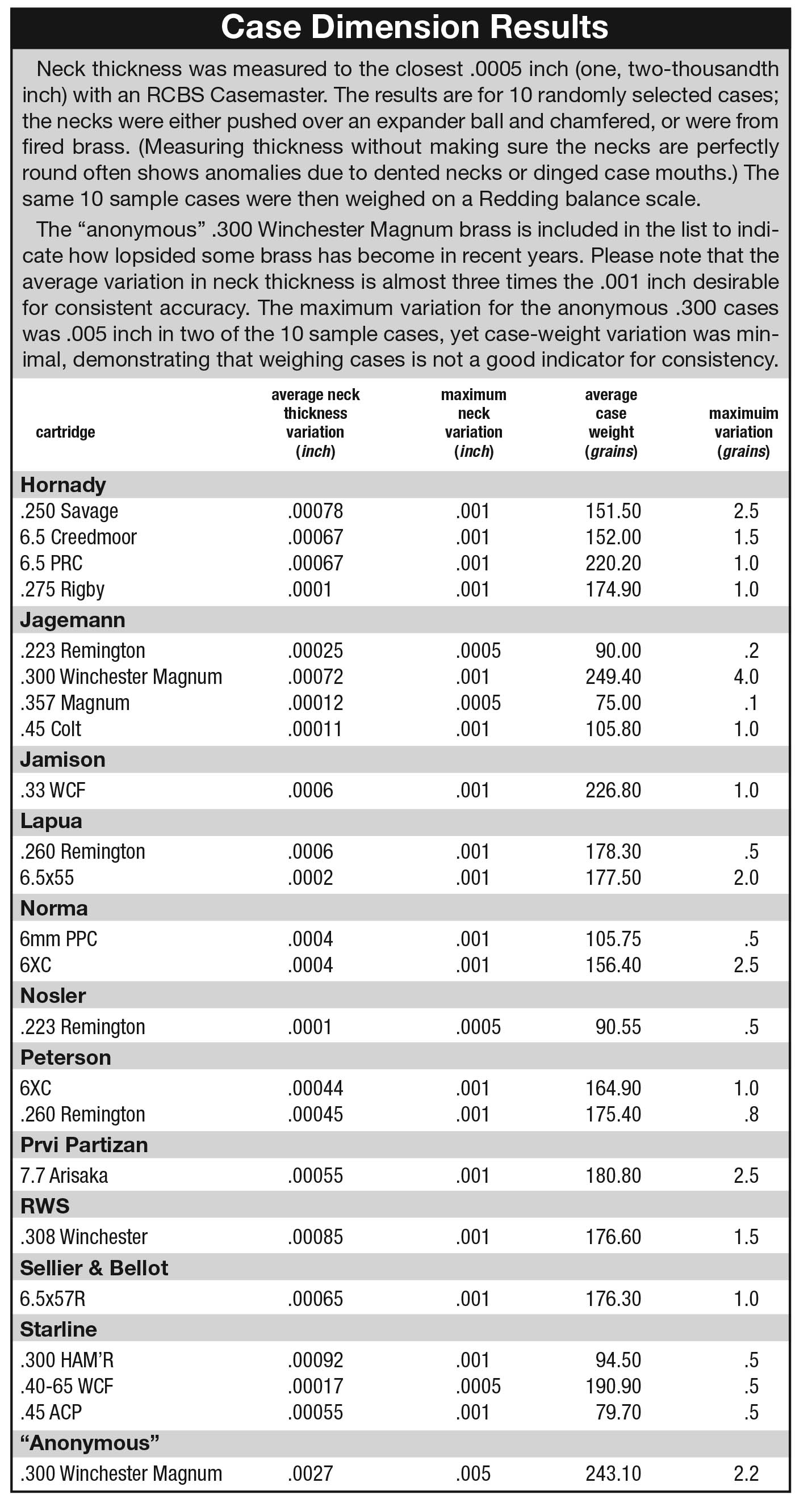

Longer-range shooting became popular due to the availability of affordable laser rangefinders. As a result, many handloaders became even more obsessed with accuracy and “discovered” brass with more consistent, concentric dimensions was among the most important factors. Essentially, cartridge cases function as part of the rifle. No matter how precise the chamber, if the case is lopsided, then the chamber is also lopsided. Case necks of even thickness result in bullets entering the bore straighter and also indicate consistent case walls, which result in straighter brass after firing and resizing.

Consequently, during the 1990s I started measuring the neck thickness of each new batch of brass, culling cases with a thickness varying more than .001 inch. This made a measurable difference in accuracy, but many handloaders started bragging about Lapua cases made in Finland. These not only had consistent dimensions but also tough case heads, preventing primer pockets from expanding with stout powder charges often used by long-range shooters. As a result, Lapua cases lasted longer, justifying their higher price.

The Lapua .243 brass was also very consistent in weight, which many handloaders apparently think is more important than neck thickness. It is not, because necks are the “steering wheel” for bullets.

Minor variations in case weight primarily affect muzzle velocity, often so slightly the difference cannot be measured on a typical chronograph. Yet quite a few handloaders sort every batch of brass by weight while never measuring neck thickness.

Before the Internet, any handloader desiring specialized brass had to persuade a local sporting goods store to order some, or search the paper catalogs of the few mail-order companies offering such brands. The Internet changed all this; new brass companies could also sell directly to customers, resulting in lower prices.

The third factor was the 2008 presidential election. Many people have called Barack Obama the greatest salesman the American

Since traditional brass suppliers of primarily made ammunition, empty cases were available only after ammunition production. Component brass became scarce because manufacturers could sell almost all the ammunition they made.

Also, making brass for dozens of different cartridges requires extra time to switch tooling and in manufacturing, time is money. As a result, factories concentrated on making brass for popular factory rounds such as the .223 Remington, .243 Winchester and .30-06. Less popular cartridges like the .25-35 Winchester or the 7mm Remington Ultra Mag, were produced “seasonally,” which meant rarely.

Factories also tended to run their case-forming dies longer before replacing them, so neck and case-wall thickness started varying more. Until the early 2000s I could neck-sort new brass and, at most, reject around 20 percent of the cases. A few years later the rejection rate was often 50 percent and sometimes much higher.

Cases were also occasionally made of softer brass because it was easier on tooling yet strong enough for most factory loads. One example from my experience was a new 50-round bag of .257 Roberts brass that stuck firmly in chambers when fired with published +P data which, despite the designation has even lower pressure than .30-06 data.

As a result, many sporting goods stores now stock Hornady cases, one reason I have used a bunch over the past few years for handloading various rounds from the 6mm Creedmoor to the .275 Rigby and .300 Weatherby Magnum. In each cartridge, necks have never varied more than .001 in thickness. (See accompanying table for neck measurements and weights of various brands.)

In more traditional cartridges, one notable Hornady addition is .250 Savage cases. Many knowledgeable .250 handloaders started using necked-up .22-250 cases because some factories run their .250 forming dies too long, resulting in lopsided brass and mediocre accuracy. The Hornady .250s are very consistent, resulting in fine accuracy with my present Savage Axis with an after-market Shaw barrel.

Jagemann Sporting Group has been making component brass for years, but usually for other companies. After starting to market cases under its own name, .223 Remington and .300 Winchester Magnum samples were provided, along with .357 Magnum and .45 Colt, the two handgun cartridges I load most often. All were exceptionally consistent and, best of all, the .300 Winchester brass turned out to be tougher than the brand usually used in my Heym SR-21.

Jamison Brass & Ammunition primarily makes cases for older cartridges. I most recently used some for a Handloader article on the .33 WCF that resulted in fine accuracy with a Marble’s aperture sight and the factory front bead on a takedown Model 1886 Winchester. Yes, uniform brass can shrink groups even in such an antique rifle.

Lapua continues to make excellent brass. I’ve used it regularly in several rifles, but perhaps most notably with a custom 6.5x55 based on an FN Mauser commercial action, using warmer data for “modern rifles” rather than old Krag-Jorgensons or pre-’98 Mausers. Despite higher pressures, all the cases still have tight primer pockets, and the rifle shoots very accurately since the 1:8 rifling twist Lilja barrel was chambered with a minimum-throat reamer from Pacific Tool & Gauge.

Despite Norma selling brass in the U.S. for a very long time, some comments seem in order. The very first component brass I purchased was Norma 7.62x54R “Russian” for a Mosin-Nagant rifle I sporterized at age 13. At the time, Norma was the only company offering Boxer-primed 7.62x54 cases, and the Powder Horn in Bozeman, Montana, ordered two boxes. Since then Norma brass has fed my rifles in at least several dozen chamberings.

Some handloaders claim all Norma brass is “soft,” and while cases for older, low-pressure rounds might tend to be, probably to ensure sure they seal the chamber, Norma cases in several higher-pressure rounds have proven quite durable. A good example is my 6mm PPC benchrest rifle made by now-retired gunsmith Arnold Erhardt. When purchased in 2010, Lapua PPC cases were in short supply, so I bought 100 new Norma cases instead. The neck thickness and weight proved very consistent, though the necks still had to be lathe-turned because of the chamber, like most benchrest 6mm PPCs requiring cartridges with necks no thicker than .262 inch.

Aside from the PPC, I have also used the same batch of Norma/Weatherby cases in a pair of .257 Weatherbys since 2004, and the same batch of Norma 9.3x62 cases in a CZ 550 since 2001. The Weatherby cases have always been loaded right up there, lately with the maximum Hodgdon-listed charge of H-1000 and Nosler 100-grain E-Tips. The 9.3x62s have been loaded to lab-tested pressures of 60,000 psi and often shot in Africa in temperatures of 90 to 105 degrees Fahrenheit. Their primer pockets remain tight as well, and both rifles are very accurate.

Nosler started offering component brass over a decade ago, but at first it was all made by other companies, including Norma. Eventually, however, Nosler’s expanding line of ammunition and component brass required a more consistently available supply, so Nosler bought Silver State Armory, a brass manufacturer in Washington, and moved the equipment to Oregon. The eventual goal was to produce all Nosler brass in-house, and as of mid-2018 the majority is made there, headstamped both Silver State and Nosler. The .223 Remington Nosler brass tested, a box of its pre-sorted and “prepped” cases, proved to be among the most consistent brass measured.

Peterson is a new U.S. brand sold exclusively by Graf & Sons from which I order a lot of my handloading components. Peterson makes brass primarily for rifle cartridges used for longer-range shooting, from the 6mm Creedmoor on up to the .408 Chey-Tac. Peterson provided a couple of boxes of .260 Remington brass, which proved so good I ordered 100 6XC cases from Graf & Sons (apparently a “special run” since 6XC brass is not listed on the Peterson website). As the table reveals, the 6XCs are very consistent.

Starline originally made only handgun and black-powder cartridge brass. I started using Starline cases because as one friend put it, “They’re the Lapua of handgun brass.” They proved to be very consistent, as did some .40-65 rifle cases I reformed to .33 WCF.

Starline recently entered the modern rifle market. So far my only experience is with the .300 HAM’R, Bill Wilson’s new feral pig cartridge that was covered in Handloader No. 318. The brass proved to be extremely consistent, one reason the 7-pound Wilson AR-15 shot so well.

I also tested several European-brand cases, both in foreign cartridges and various other rounds such as the .308 Winchester. The RWS .308 cases came from some factory ammunition loaded with UNI 180-grain Classic bullets, which in several rifles proved to be the most consistently accurate .308 hunting ammunition I have ever tested. The brass from this factory ammunition proved to be as consistent as match brass, and as somebody once commented, “RWS cases are as hard as woodpecker lips.” They may cost a lot, but they basically last forever.

One semi-surprise in the Eurobrass was Prvi Partizan cases purchased recently for an upcoming article on the 7.7 Japanese Arisaka. I must confess not anticipating anything great, not because Prvi Partizan is a Serbian company, but because I wondered, why would any company bother to make good brass for a cartridge that is not normally used in modern, super-accurate rifles? The 7.7 cases, however, turned out to be very consistent.

The Sellier & Bellot 6.5x57R cases on hand are from factory loads available from several Internet sites, including Graf & Sons. After handloading for a Sauer drilling, they resulted in five-shot, 100-yard groups in the one-inch range, and not just with one bullet but several. This is unusual accuracy for a drilling, but I bought it from my drilling-loony friend Bruce Cunningham, who reported it was among the most accurate of the more than 200 three-barrel guns he has owned.

From the evidence, it appears handloaders are now living in a golden age for rifle brass. I’m looking forward to trying more in the future!