Reloader's Press

Bullet Seating Depth

column By: Dave Scovill | April, 19

Every now and then a reader writes to ask about bullet seating depth with cast or jacketed bullets, mostly concerning revolvers and, occasionally, semiautomatic pistols. The question concerns pressure. As a rule, seating the bullet deeper causes pressure to increase somewhat, and seating the bullet out a bit reduces pressure. The problem is that readers who contact the office almost never mention the overall loaded length (OAL) they want to use in relation to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) or quoted standard for the bullet in question. That is, OAL compared to what?

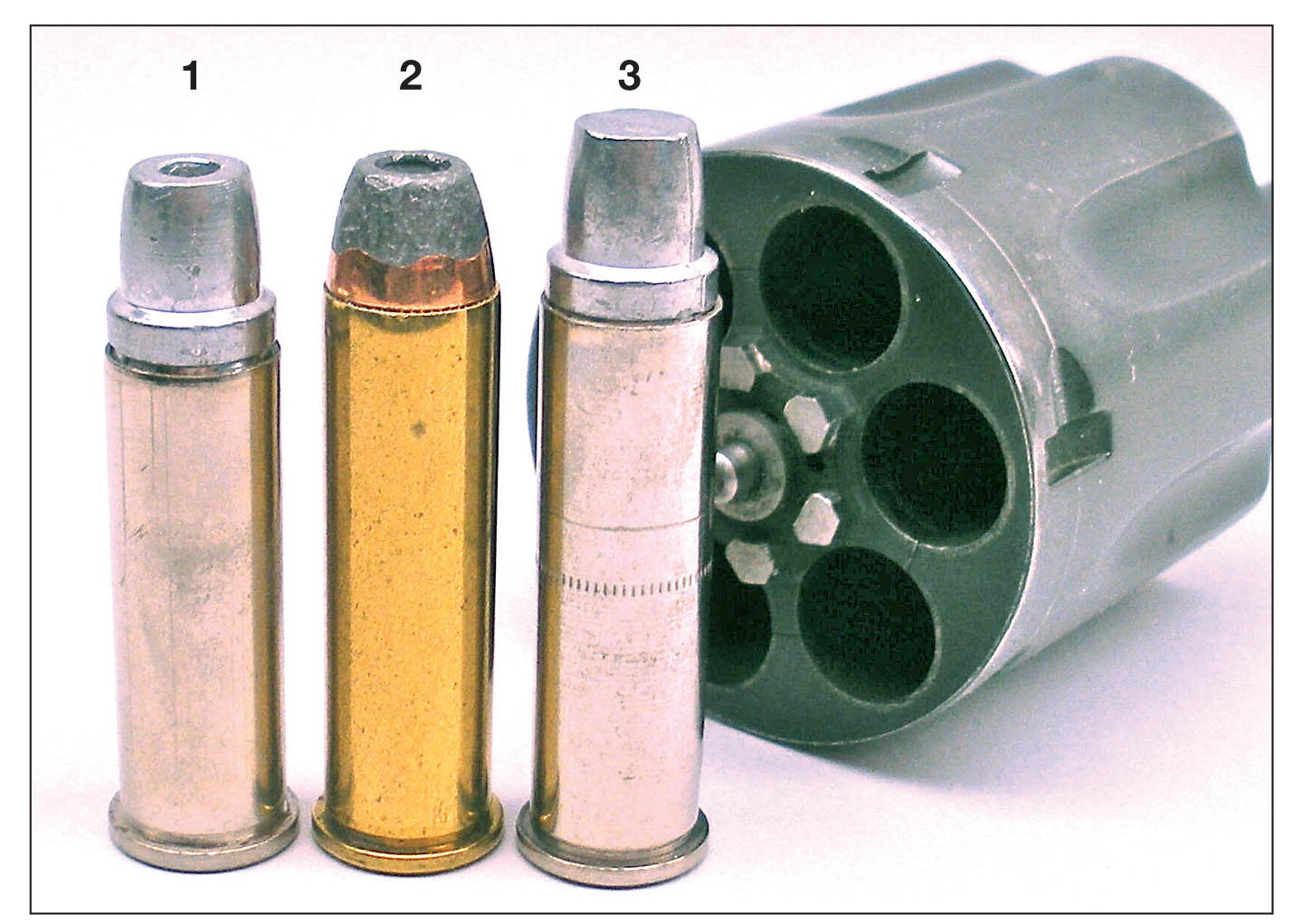

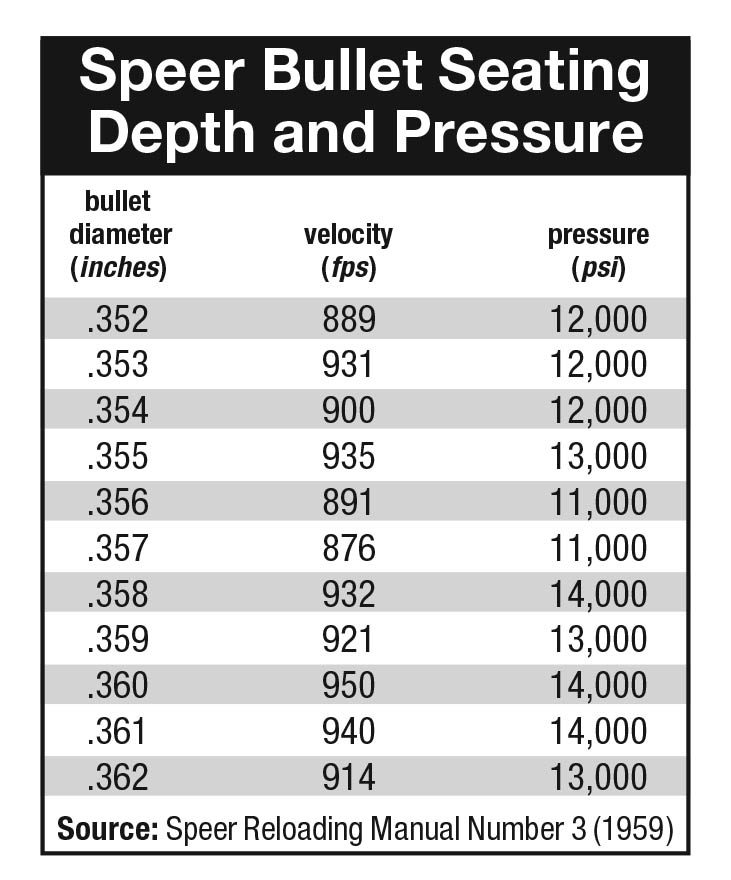

Back in 1959 Speer addressed the subject of pressure as it relates to bullet seating depth and published the results in its Reloading Manual Number 3. That was also the year Speer introduced its half-jacket semiwadcutters in .38 and .44 calibers, both in hollowpoint and softnose configuration. Using the then-new .357-inch bullet design in the .38 Special, Speer crimped the bullet at the base of the nose (in) and at the front edge of the half jacket (out) 1.370 inches. Using 5.0 grains of Unique, the bullet seated in produced 16,000 psi. Seating the bullet out produced 12,000 psi. Velocities were 967 and 861 fps, respectively. For whatever reason, OAL for the two seating depths was not given. The OAL listed above is taken from Speer Reloading Manual, 14th Edition.

Speer went on to conclude “ . . . (1) bullet diameter may often have a considerable effect on accuracy but evidence so far indicates it has little effect on pressure and velocity. (2) Bullet seating depth into the cartridge case has more effect on pressure and velocity than does a crimp or lack of crimp on the bullet. (3) Loads with semi-jacketed bullets result in more uniform velocity and pressure than loads with cast bullets. (4) Conventional crimp-seating methods applied to semi-jacketed swaged bullets do not result in optimum accuracy. Bullets should be seated in one operation and crimped in a second operation.”

by Bill Caldwell have been reprinted a couple of times, and I have summarized those tests in my book, Colt’s Single Action Army, Loading and Shooting the Peacemaker (2013). It would appear the subject of pressures and seating depth with the Speer half-jacketed semiwadcutter came up in 1959 because the bullet did not have a crimping groove, and the majority of cast revolver bullets did. Most factory loads for handguns at the time had plain base or hollowbase lead, and/or lead with gas check bullets.

As a rule, when using cast bullets with a crimping groove, crimp the bullet in the groove. For jacketed bullets with a crimping cannelure, crimp the bullet in the cannelure. If a cast or jacketed bullet does not have a crimping groove or cannelure, chances are it was designed to be seated in a semiautomatic cartridge, in which case it needs to be seated to the recommended OAL listed for that bullet in references and/or loading manuals using a taper crimp. Examples that are exceptions to that are original .38 and .44 WCFs, .44 Special and .45 Colt lead bullets, sans crimping groove, that were designed to be seated over a full charge of black powder and crimped on the forward edge of the ogive.

Assuming a loading project begins with the bullet of interest seated to the suggested or published OAL, stick with that length and don’t change it. If the OAL is changed, go back to the starting load and begin again while watching for signs of excessive pressure, such as cratered primers or exceptionally high velocity, etc.

Prior to the 1940s, Elmer Keith came up with cast bullet designs with crimping grooves for the .38 Special (Lyman No. 358429) and .45 Colt (Lyman No. 454424). When the .357 Magnum came out, the nose of the .38-caliber semiwadcutter was too long to be crimped in the appropriate groove and still chamber in some magnum cylinders. The only choice was to seat the bullet deeper to crimp over the forward edge of the first driving band.

The same problem cropped up with Keith’s .45-caliber semiwadcutter that was designed for the Colt .45 Colt SAA, and pre-1978 Smith & Wesson cylinders were too short,

It is also important to bear in mind that nearly all .38- and .44-caliber jacketed bullets made currently are designed with a crimping groove established for an OAL in the .357 and .44 Magnums, i.e., maximum of 1.590 and 1.610 inches, respectively, whereas maximum OAL for the .38 and .44 Specials are 1.55 and 1.615 inches. The crux of this is that most .38- and .44-caliber jacketed bullets are seated deeper than necessary in .38 and .44 Specials because of the placement of the crimping cannelure to facilitate the proper OAL in magnum revolvers.

It is also significant to note that the vast majority of .38- and .44-caliber jacketed bullets are designed to withstand higher impact velocities of 1,300 fps maximum and pressures of 35,000 and 36,000 psi, respectively, than they would be subjected to when loaded in the Specials. As a result, jacketed bullets do not expand to form a gas seal in somewhat oversized chamber throats at 17,000 to 21,000 psi in .38 Special chambers and 15,500 psi in .44 Specials. Neither do these “magnum” bullets expand appreciably at Special velocities in test mediums such as ballistic gelatin or soaking wet newsprint. The exceptions are those .38- and .44-caliber jacketed component bullets that were generally manufactured for the .38 and .44 Special factory loads, e.g., personal protection, or short barrel loads.

It is possible to establish an additional crimping cannelure on .38- and .44-caliber jacketed bullets to avoid seating them so deeply in shorter Special cases, but all published load data is developed at the stated OAL in various loading manuals.