The Great Three-Eighty

A Browning Invention Comes of Age - 110 Years Later

feature By: Terry Wieland | April, 21

Having less powder capacity, the .380 naturally propels a lighter bullet (typically 90 or 95 grains) at a lower velocity (rated at 955 fps) than the Luger, which has a factory rating with a 115-grain bullet at 1,140 fps. Twenty grains and 200 fps is a big difference in a small pistol. Does that make the .380 useless? Hardly.

For one thing, it can be chambered in a smaller, lighter, more compact gun. Aside from the Colt 1903 and Browning 1910, probably its most famous chambering was in the Walther PPK, and the list of other companies and models goes on, seemingly forever. At least five European countries regarded it highly enough to make it their official military round, and a couple retained it as late as 1945.

Pistols, cartridges, powders and bullets have all come a long way since 1945, and the fact that the .380 has hung on throughout that time suggests it has something to offer that can’t be found elsewhere. Instead of comparing it to more powerful rounds like the 9mm Luger, it should be considered alongside the .25 and .32 ACP, which are the rounds typically chambered in small pistols like the PPK. Looked at that way, the .380’s ballistics suddenly seem pretty good: Its 95-grain bullet at 955 fps for 192 foot-pounds eclipses both the .25 (50 grains, 810 fps, 73 foot-pounds) and the .32 (71 grains, 960 fps, 145 foot-pounds).

The .380 has always been far more popular in Europe than the U.S., and this is reflected not only in the number of companies that have chambered it, but in the pistols to be found, new or used, today. Aside from Colt, High Standard, Remington and Savage made .380s, but they don’t seem to have made many considering how few show up for sale.

As is always the case, progress in one area sparks improvements elsewhere, but the changes don’t always keep pace with one another. Ammunition manufacturers generally produce runs of different calibers according to a schedule based on previous sales patterns. A sudden surge in popularity of .380s does not immediately lead to a surge in ammunition production. Accustomed to modest sales for the better part of a century, the big ammunition companies seem to have been unprepared for the rush to buy .380 that took place throughout the latter half of 2020. As a result, not only is ammunition in short supply, so are all the components necessary for loading your own.

For example, on October 28, 2020, I received an email advisory from an ammunition dealer announcing that it had found some supplies of .380 hidden away, and was prepared to sell it at $199.00 for 100 rounds (two 50-round boxes). That is two bucks a cartridge, plus shipping. At the same time, a quick review of both Graf’s and Midway USA revealed that they did not have a single .380 bullet in stock. They still had some heavier bullets suitable for the 9mm Luger, but none of the 65- to 100-grain slugs for the .380.

Let’s start with all the limitations. First, the cartridge is small for its caliber, which places a limit on bullet weight. Anything more than 100 grains cuts into powder capacity and reduces velocity. As well, overall cartridge length is critical in order to fit the typically single-stack magazines. Anything more than the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) specification of .984 overall cartridge length is likely to hang up.

Since .380s are 99.99 percent self-defense guns (the other 00.01 percent being rather expensive plinking), reliability of feeding, chambering and ejecting is of paramount importance. No possible ballistic or accuracy advantage to be gained by goosing loads or changing overall length can trump operational reliability. Period.

Something very much to keep in mind is that .380 pistols are small semiautos designed to function based on the standard factory specs of the round. If you use a bullet that is too light, regardless of velocity, you may find there is insufficient recoil to cycle the action. This can cause a failure to eject and/or chamber a new round, and/or failure to cock the gun and/or a stovepipe jam. I experienced all of the above (extremely rarely), but always with the lightest bullets or a very light load.

Historically, the .380 was loaded with a round-nosed jacketed bullet – maybe not the best in terms of stopping power, but easily the most reliable for feeding both in the magazine and into the chamber. Bullets with odd-shaped noses can grab the side of the magazine and jam, or dig into the feed ramp. Again, close attention to maximum overall length is critical.

The .380 was designed as a true rimless cartridge (unlike the semi-rimless .32 ACP) and was intended to headspace on the case mouth. I experienced no case stretching, but it’s a point to remember, especially if mixing different makes of brass.

This brings us to the brass itself. I ended up using a wide variety, some of which was never intended by the manufacturer to be reloaded. While it all used Boxer primers, some of the primer pockets were so tight that primers could not be seated. This was a particular problem with Aguila brass, but I found that as soon as I encountered resistance, I could take out the case, ream it slightly to chamfer the pocket and all was well. Attempt to force the primer in, however, and you can find yourself with a very tricky problem involving a jammed case and a live primer.

As with the .32 ACP, the .380’s tiny case is tricky to handle. It is also rather delicate and can be damaged easily with too much pressure applied. Most people think that it’s simply the 9mm Luger, only 2mms shorter, but in fact it is dimensionally smaller everywhere. Try putting a 9mm Luger case into a .380 shellholder and you’ll see what I mean; conversely, using a 9mm Luger shellholder for the .380 gives an insufficient grip on the rim, which can cause damage, leading to feeding, chambering and ejection problems.

Since the .380 headspaces on its case mouth, this needs careful attention. Particularly, it should be very slightly belled – so slightly you can barely see or feel it – just enough to allow the bullet to enter the case. Then, when it’s seated, the case provides all the grip necessary to hold the bullet, and generally needs no extra crimp – which is good, since .380 bullets rarely have a cannelure or crimping groove anyway.

If loading ammunition for defense purposes, I would use either new or once-fired (and carefully conditioned) brass. When I began work on this, however, there was no supply of new factory brass available, so I used a mixture of different brands, mostly once or twice fired. Some of it was brass picked up on the range, of indeterminate origin. An interesting point is that there were remarkably few malfunctions of any kind. Using a Smith & Wesson M&P Shield EZ, at one point on the range I fired 190 rounds and had a grand total of four malfunctions, as noted above, all with either the lightest bullets or a very light load. Overall, the reliability was exemplary.

Most .380 pistols have rear sights that are either fixed or minimally adjustable. My approach is to sight-in with my defensive load, then try to find a practice load that prints fairly close to it. My preference is factory Hornady Critical Defense with the 90-grain FTX bullet. This is not to say a handloader can’t load his own tactical load, only that I prefer not to, especially in a semiauto.

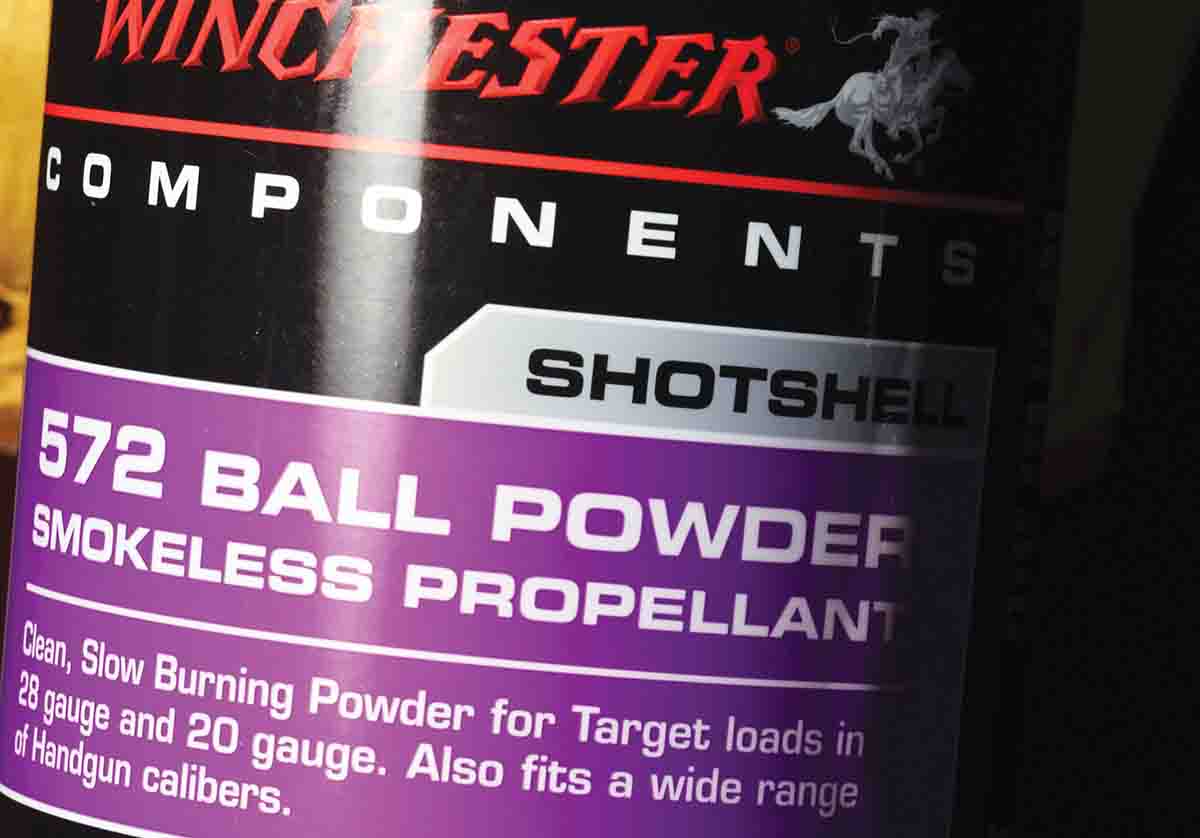

As the table indicates, some of the loads delivered admirable accuracy. The single best group was with Winchester’s W-572 and the 100-grain X-TREME – a tight cluster of four shots measuring 0.6 inch, with one flyer expanding it to 1.64 inches. Winchester 572 also did well with the 95-grain Speer.

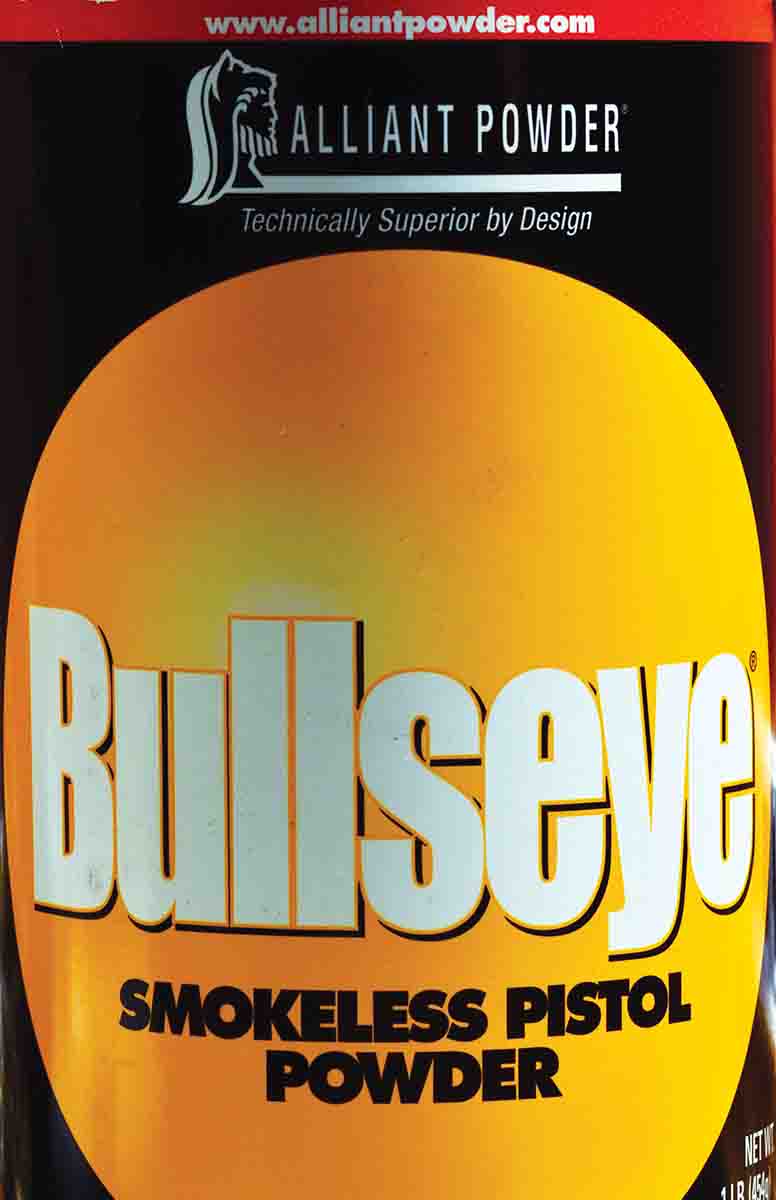

Overall, the best powder with all bullet weights was Titegroup. Although all the loads were Hodgdon’s listed maximums, ballistic performance was midrange. Accuracy was consistent and there were no malfunctions of any kind. If I had to use just one powder for the .380, Titegroup would be it.

Of the five bullets used, Speer’s 95-grain TMJ (Total Metal Jacket) stood out for both its accuracy and reliability in all phases of feeding and operation. Its margin of superiority is razor-thin, however, and no bullet was bad in anyway. The two Lehigh bullets are intended for defensive use and priced accordingly. The Lehigh 65- and 90- grain bullets appear outwardly identical, with a nose like a Phillips screwdriver, but the lighter bullet has a machined hollow base, which accounts for the price difference.

If there is one overall impression I have from the testing that took place, it’s that the .380 as chambered in the S&W Shield EZ is remarkably reliable with a wide variety of loads, bullet types and different makes of brass. During the one long (190-round) testing session, there were only four failures, and all four could be attributed to the load being not quite powerful enough to cycle the action properly.

Altogether, with the bullets and powders available today, the .380 ACP is a far cry, ballistically and tactically, from where it began in 1908, or even what it was as recently as 1980. For a small, easily-concealed pistol that packs enough power to handle most situations but is also manageable for almost anyone, it’s a hard little cartridge to beat.

.jpg)