Vihtavuori Rifle Powders

Often Overlooked, Always Accurate

feature By: John Barsness | April, 21

They also often say that a loss of 100 fps results in only slightly more bullet drop at 400 yards. This is also true – but the problem with cold-sensitive powders is not trajectory, but a significant change in impact at 100 yards, which can be in any direction. My tests have found a shift of up to 3 inches at 0 degrees Fahrenheit, after the rifle was sighted-in at 70 degrees Fahrenheit – which amounts to a foot at 400 yards. I have yet to see any noticeable change in impact with powders advertised as temperature resistant, or change in muzzle velocity at zero Fahrenheit of over 30/35 fps.

Many handloaders also believe decoppering agents are a recent development, and perhaps even marketing fiction. In reality, decoppering originated over a century ago in artillery shells, due to fouling so severe that strips of copper sometimes hung from cannon muzzles.

Vihtavuori also claims less lot-to-lot variation than occurs with most other powders. I have been using them for over a dozen years now, and have yet to find more than about one percent variation in different batches, while many other rifle powders vary 2⁄3 percent, and occasionally even more.

Such high tech powders are highly regarded by target shooters, who buy a LOT more powder than hunters, definitely affecting marketplace trends. Accuracy is far more consistent at varying temperatures, and when shooting dozens or even hundreds of rounds during a match, it’s the major reason so many new powders appeared in the last quarter-century.

Today, more and more hunters also use such advanced powders for the same reason – consistent accuracy. I am primarily a hunter, and have grown quite fond of “temp-resistant” powders, due to mostly hunting in my native Montana, which happens to be the American state with the widest recorded range of temperatures, from -70 to 117 degrees Fahrenheit. While those all-time readings are obviously unusual, I have personally experienced Montana temperatures from -58 to 113 Fahrenheit, and have hunted deer at -40 and prairie dogs at 105 Fahrenheit.

Today, even more handloading hunters are becoming obsessed with finer accuracy, often due to handloading becoming popular as an off-season, “adjunct hobby” to hunting. Even some deer hunters who rarely shoot beyond 200/250 yards like to work up super accurate handloads, because they compete formally or informally with their handloading/hunting buddies.

Now, we can debate the ethics of “long-range hunting” forever, but one aspect that cannot be debated is how it resulted in specialized target games such as the Precision Rifle Series, where competitors shoot at unknown ranges out to well over 1,000 yards. This, of course, resulted in even more hunters trying (and burning) more “target” powders.

So far, both “temp-resistance” and decoppering are not absolute. Several manufacturers make powders that result in the same muzzle velocity at “normal” temperatures of around 70 degrees Fahrenheit and cold down to below zero. However, as temperatures rise over about 80/85, every powder I have ever tested gains velocity. However, temperature-resistant powders do gain less velocity (and hence pressure) in warmer weather, sometimes a lot less.

The same caveat applies to decoppering agents. I have yet to encounter a decoppering powder that eliminates any trace of copper fouling, as revealed by my Hawkeye borescope, except in those unusual barrels that almost refuse to copper-foul in the first place. Still, decoppering agents do reduce copper buildup considerably, exactly how much depending on the individual barrel and bullet, and the amount of powder relative to the bore. A 7mm Remington Magnum, for instance, uses far more powder (and hence decoppering agent) than a 7mm-08 Remington, so it tends to build up less copper.

The first decoppering agent was lead wire or foil placed on top of the powder charge. During the heat and pressure of firing, the lead combined with the copper to produce a brittle mix, which blew out of the muzzle along with the hot powder gas. Soon it was discovered that bismuth and tin resulted in the same effect, the reason they’re used as decoppering agents in today’s smokeless powders: Both are environmentally safe.

The first Vihtavuori powder to gain significant traction among American target shooters was N133, probably still the leading powder among short-range benchrest shooters, a sport almost completely dominated by the 6mm PPC-USA cartridge. While some shooters use other temperature-resistant powders such as Accurate LT-30 and LT-32, or Hodgdon H-322 or Benchmark, N133 still tends to lead the list at most shoots.

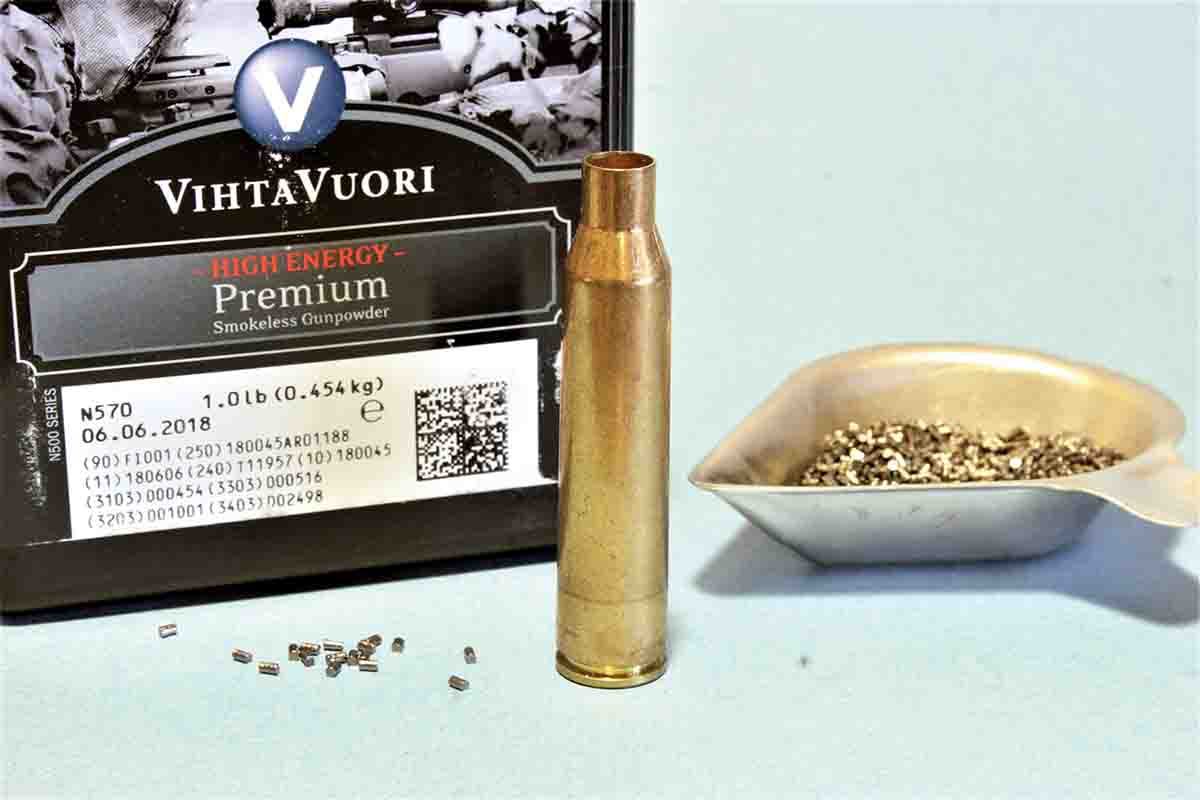

In fact, Vihtavuori’s success in target competition led the company to introduce powders designed for specific cartridges. One of the first I tried was N570, introduced about a decade ago, a very slow-burning powder specifically designed for heavier bullets in the .338 Lapua Magnum. N570 eventually proved to be the most consistent performer in a Savage 110 BA I had long enough to learn as much about the .338 Lapua as I could tolerate.

With one exception noted later, Vihtavuori does not give its powders catchy names suggesting possible uses or super powers. Instead, the company uses numbers, with higher numbers indicating slower burn rates. The 100-series rifle powders, such as N133, are single-based, containing only nitrocellulose as the fuel. The 500 series, such as N555, is double-based powders with added nitroglycerine for extra energy and hence velocity.

The 500s are all strictly rifle powders, while the fastest burning 100 powder, N110, is “suitable especially for small rifle cases like [the] .22 Hornet [and] .30 Carbine, but also Magnum pistol and revolver cartridges like .357 Smith & Wesson Magnum, .41 Magnum, .44 Magnum, .454 Casull and .500 S&W.” (Vihtavuori also manufactures powders specifically designed for handguns, shotguns and rimfire ammunition, designated as the 300 series. These include Tin Star N32C, a smokeless powder designed for Cowboy Action Shooting, that simulates the burn characteristics of black powder – the company’s only “named” powder.)

Some of my past results with Vihtavuori powder are listed in the handload table. While working on this project, however, I tried some powders not tested previously, and retested several older loads by playing with bullet-seating depth, primers, etc. Here are specific comments on some of the loads.

The .17 Hornady Hornet load using N120 is listed in Hornady’s manual, but was originally tried with a newer .17-caliber bullet rather than the 20-grain Hornady V-MAX used. The maximum charge of 10.8 grains resulted in fine accuracy but a muzzle velocity only a little over 3,300 fps while Hornady lists 3,600 fps.

This time I tried the 20-grain V-MAX, seated to Hornady’s listed maximum overall length of 1.720 inches, but also switched the primer to the Winchester Small Rifle Hornady used in its tests. Winchester does not make a “magnum” small rifle (SR) primer, but its standard SR primer is hotter than many, including the Remington 7½ used in my original trial. Accuracy was similar, but velocity jumped to a little over 3,600 fps, despite the barrel on my CZ 527 being a couple inches shorter than the Savage Model 25 used by Hornady. (The .17 Hornet is not listed in Vihtavuori’s load data, but many other sources include its powders, often for cartridges not listed on Vihtavuori’s website at vihtavuori.com.)

One powder I had never used before was N110, in my latest .22 Hornet, a BSA Model 15 Martini single-shot converted from .22 rimfire. The average velocity was just about exactly the same as Vihtavuori’s data, but accuracy was not quite as good as with Hodgdon Lil’Gun powder. I suspect switching to a hotter primer, such as the CCI 450 Small Rifle Magnum used in my Lil’Gun loads, might enhance both velocity and accuracy, but the testing took place during a far windier November than normal, limiting range time, so the primer retest will have to wait.

The N133 test for this article was also limited due to windy conditions, plus the fact that Berger discontinued the 65-grain flatbase target bullet used in my previous 6mm PPC target loads. Instead, I substituted Berger’s 68-grain flatbase target bullet, seating it as closely as possible to the same land distance as the 65-grain bullet. Five-shot groups averaged .200 inch – not bad, but not quite as good as the best loads with the 65-grain bullet.

However, it had been a while since I shot the rifle, and the 8-ounce trigger got away from me now and then, resulting in one “flier” in each group. The other four shots in each group averaged .149 inch, a little better than any of the loads worked up with the 65-grain bullets. With a little tweaking I suspect this might be the rifle’s new top load.

The 6.5 Creedmoor load featured N555 with Hornady’s 135-grain A-Tip bullet, which I reported on in Handloader No. 323 (December 2019-January 2020). For the A-Tip article I tried three popular 6.5 Creedmoor powders, all resulting in very good accuracy. With N555 I seated the same bullet to the same depth, and they grouped significantly better than any of the other three powders and also matched the highest velocity from any of them as well.

The Vihtavuori handloads for the two aperture-sighted rifles, an M1 Garand and Lee-Enfield, happen to be the most accurate in both rifles. The Garand, however, shoots significantly better than the Lee-Enfield, no doubt due to its very good barrel. The Lee-Enfield’s bore is relatively rough, probably due to hard use with Cordite ammunition before my father’s brother bought the “sporterized” .303 at a local hardware store in the 1950s.

The listed 8x57IRS handload is the only one tried in the Sauer drilling. I purchased the gun a couple years ago, primarily for hunting ruffed, blue and spruce grouse in the local mountains, where grizzly bears have increased considerably over the past few years. While I always carry bear spray, the option of a 200-grain Nosler Partition feels comforting and would also work fine on elk.

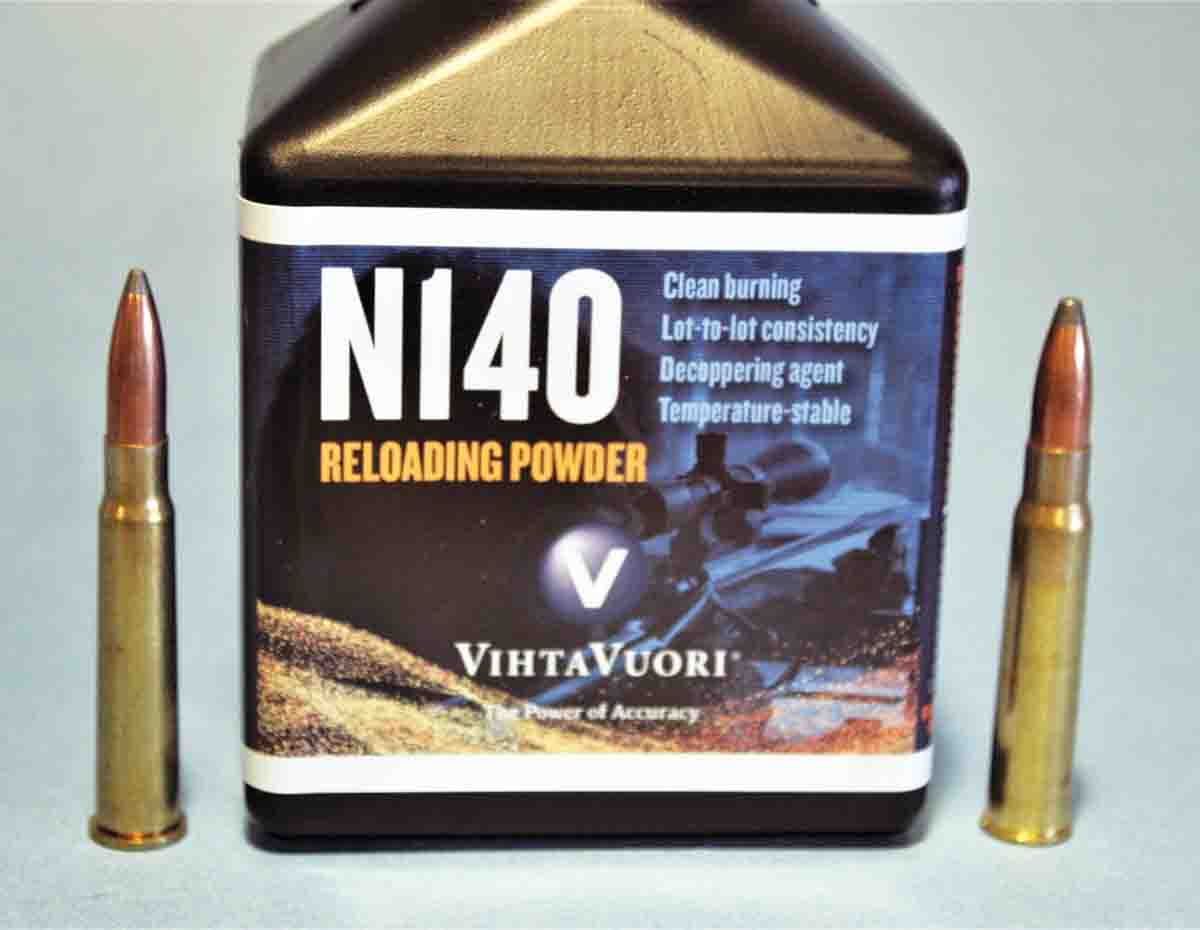

I tried N140 primarily because Vihtavuori’s online loading data includes quite a bit for rimmed European cartridges designed for break-action guns while data for the 8x57IRS is largely absent from American loading manuals. Mostly, I wanted the bullets to “regulate” with the drilling’s fixed open sights at 50 yards, since any shots at a bear, elk or deer encountered while grouse hunting would be close. The fine accuracy is a bonus.

The 100-yard accuracy level of the N570 .338 Lapua load held out to 1,000 yards, where the load grouped three shots into an average of around 7 inches. I suspect, however, that a different shooter might have squeezed even smaller groups from the combination.

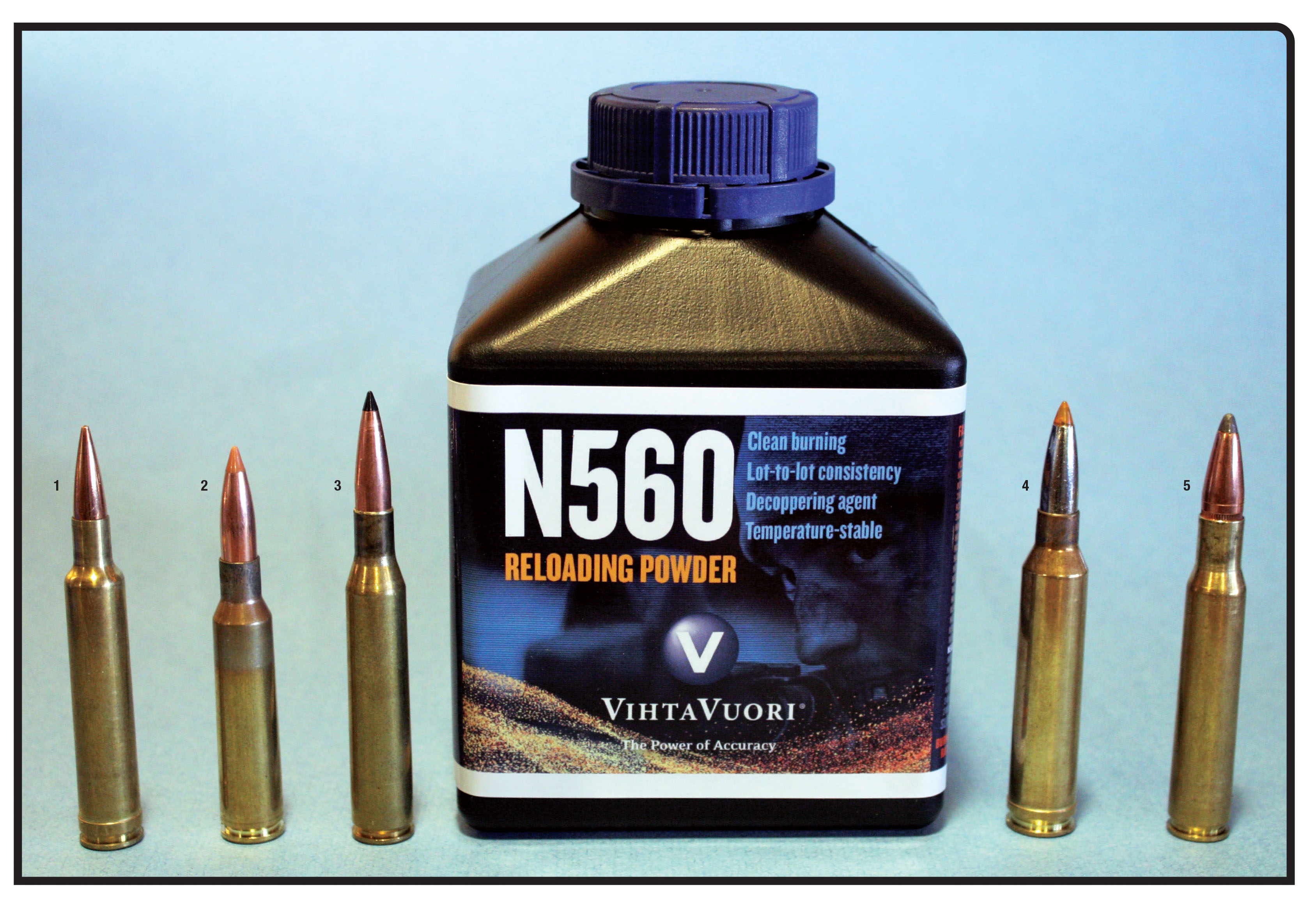

One thing I discovered when looking over the data table is that more of the handloads used N560 than any other powder. This is not totally surprising, since N560 is in the general “4831” burn-rate range, which works very well in a wide variety of modern big-game cartridges.

The relatively few average American handloaders aware of Vihtavuori powders tend to think they cost too much, meaning somewhat more than what we think of as “American” powders. (Not much smokeless rifle powder is actually made in the U.S. anymore. Instead, most is imported from factories in countries as far-flung as Australia, Canada and Switzerland.)

Handloaders have probably noticed that smokeless rifle powder tends to cost somewhat more than a few years ago, with retailers charging around $30 a pound. Right now many brands cannot be found, either in brick-and-mortar stores or on the internet, due to yet another politically-fueled buying frenzy – and each one seems to last longer. An internet search found more Vihtavuori rifle powder available than any other brand, at an average cost of $35 to $40 a pound, with 100 series powders generally priced lower than the 500s.

Personally, if a powder used for years cannot be found, I am willing to spend a little more for a different, but similar powder.

.jpg)