The Lee Loader

Genius Lies in Simplicity

feature By: Terry Wieland | April, 24

When the Lee Loader came on the market – for shotshells in 1958, followed by handgun and rifle kits in the early sixties – you could load your own for less than five bucks. This was no small thing: The post-war shooting boom brought in several million new shooters, but handloading equipment of the time was not only expensive, but much of it also required a permanent setup with a solid bench.

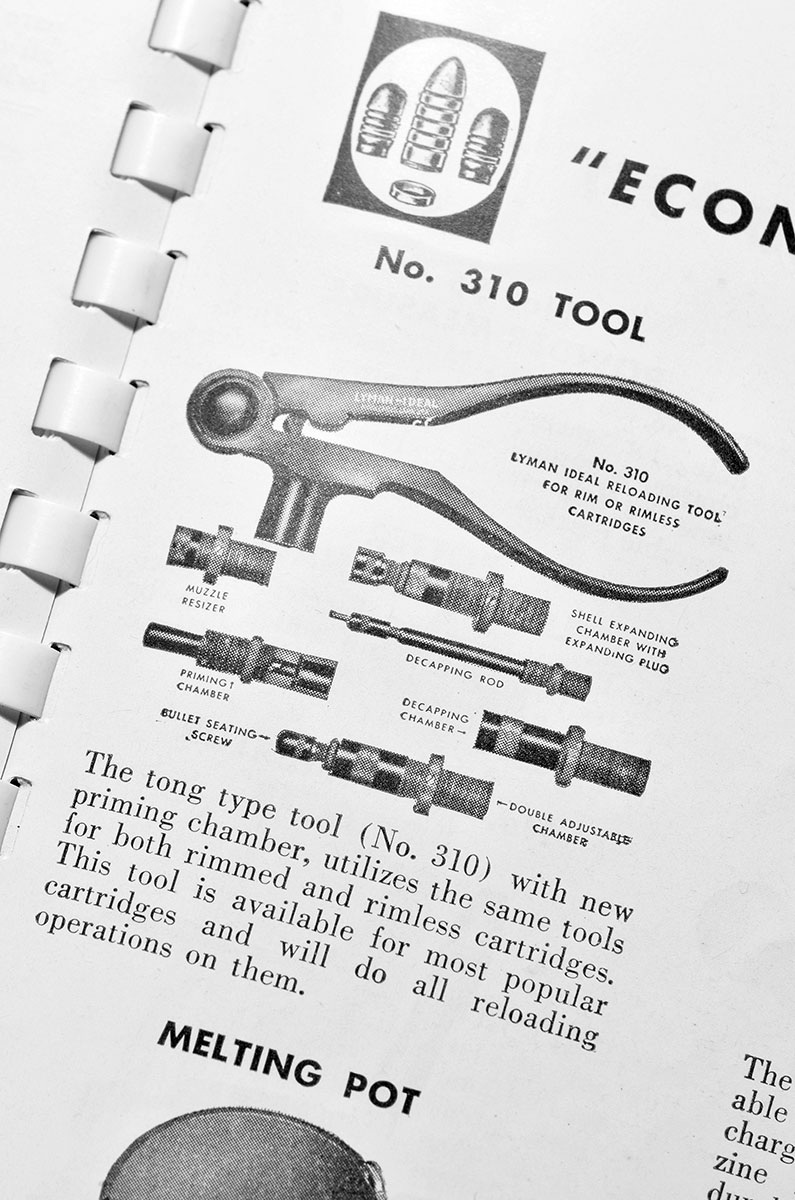

The exception was the various tong-type tools, the best-known being the Lyman-Ideal Model 310, but even it was relatively expensive and somewhat complex.

This may seem like a puzzling requirement in today’s world of large houses, but consider this: In the 1950s, Americans were in the midst of the postwar baby boom, having kids left and right, yet many were living in wartime housing. These were mostly small bungalows, with minimum space for even the essentials of living. Some had a garage, some didn’t. Just finding room to do a little handloading was a major consideration.

It’s probably no coincidence that, according to the company history, Richard Lee developed his new product working out in his own garage, and he was not alone in this. Bill Ruger and his partner, Alexander Sturm, worked in a garage while designing their 22 semiauto pistol, and look where that led.

Richard Lee died in 2018, leaving behind a substantial company that produces a wide range of handloading equipment, including presses, dies, and bullet moulds. But, more than 60 years later, they are still making the kitchen table Lee Loaders, essentially unchanged from the originals.

But back to the Lee Loader, and here I will deal mainly with those for metallic cartridges.

I bought my first one in 1968 (30-06), another in 1975 (300 Weatherby) and a third in 1976 (222 Remington Magnum). For the next decade, I did all my loading with those three kits. The latter two were the “deluxe” sets, which included extra tools for such operations as case trimming, and neck and flash hole reaming. The standard kits came in the familiar red and black box, while the deluxe kits had larger cardboard boxes with a wood grain pattern. Very spiffy.

Aside from the tools in the kit, and of course, the necessary components, all you needed was a mallet or, failing that, a chunk of hardwood kindling. (If you were working on your mother’s prized walnut dining room table, a wooden cutting board helped to forestall outraged screams.)

Handloading took a hit, however, when black powder gave way to smokeless, and suddenly the amount of propellant put in a case became critical. Instead of simply filling the case to the base of the bullet, it was necessary to weigh or carefully measure a set amount – and doing otherwise could do you in, or your rifle, or both.

Of course, handloading did not die out entirely. The tool that most typifies the first part of the twentieth century is the “tong” tool, of which the Ideal (later Lyman) is the most famous. It looks like a set of plier handles to which various implements, including sizing and seating dies, cappers and decappers, and even in some cases, bullet moulds, are incorporated or can be attached. This evolved into the Lyman 310, which was only recently discontinued.

They did, however, have some drawbacks. One was their complexity; another was the fact that if one function broke, you were out of luck. Plus, all were dependent on the pliers-type handle. Some companies attempted to improve on the Lyman 310, notably Modern-Bond and Yankee. Modern-Bond’s tool was heavier and more expensive, but no better in any way.

Lee’s individual tools were highly economical because all were cylindrical, with most manufacturing operations carried out on a lathe. This is the most consistently precise, and also the cheapest, method of producing precision implements. There is no milling, casting, or forging involved. A Lee Loader undercut the Lyman 310 in price – less than five dollars compared to six to 10 – while producing ammunition precise enough that many serious benchrest shooters produced their match ammunition with a Lee Loader. Some even used the same cartridge case over and over – a target shooter’s trick since the 1890s – and loaded each round, at the range, during the match, with the Lee.

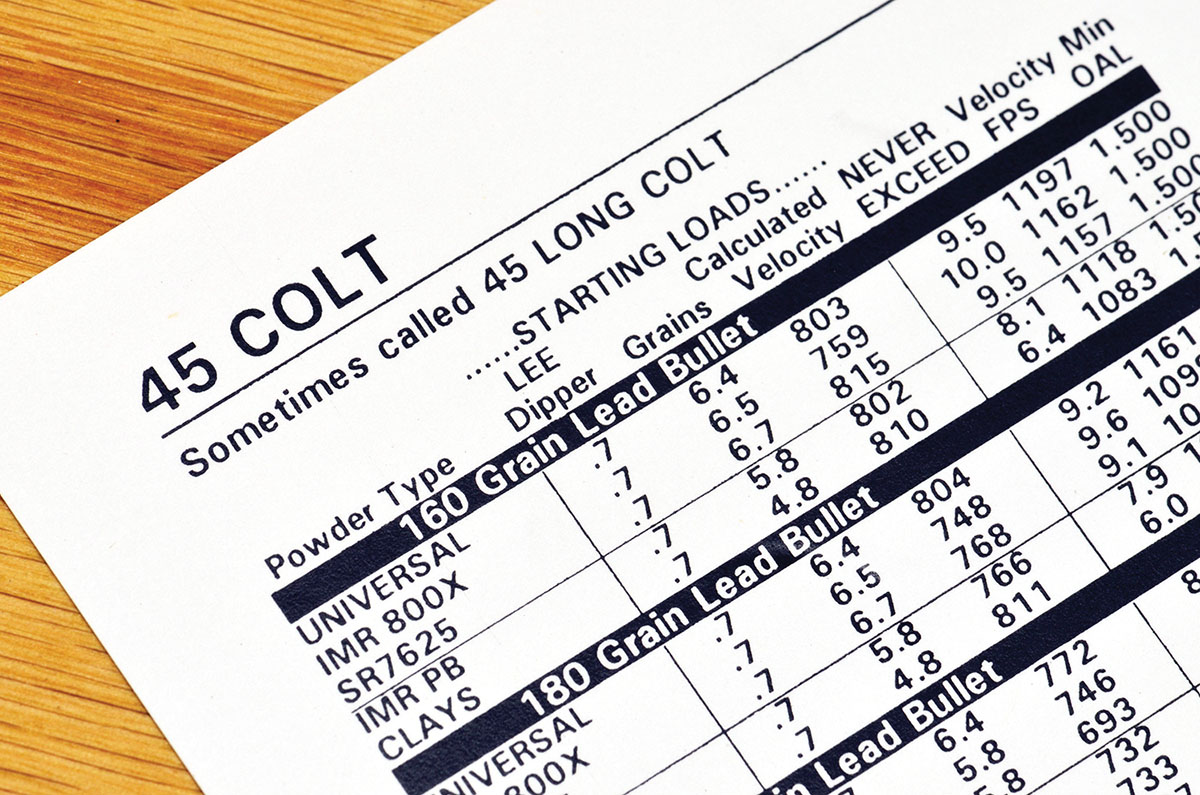

At first, I thought this was rather crude and inexact, but it’s surprising how accurate and consistent they are. The scoops are numbered, and Lee later began selling complete sets. Today, a set of 15 scoops, accompanied by a slide chart, can be purchased for less than $10.

Understandably, the powder charges recommended with each set, and delivered by the accompanying scoop, are quite light – down near the starting loads given in loading manuals. If you want heavier loads, you simply invest in a set of scoops and tailor your loads to whatever you want.

The 45 Colt set comes with a .7cc powder measure, which is supposed to produce a charge of 6.4 grains of Hodgdon Universal. A heaped scoop consistently measures 6.7 grains. With a 230-grain cast bullet, Hodgdon’s load data recommends a starting load of 6.5 grains and a maximum of 8.1.

The 38 Special kit has a .5cc scoop. It is supposed to deliver 4.7 grains of Vihtavuori N340, suitable for a 158-grain bullet, and it did exactly that most of the time. With Trail Boss, it scoops 2.3 grains, varying a tenth of a grain either way about one scoop in five.

As with most handloading operations, it takes a little practice to get the feel of what you’re doing. The key with the powder scoops is consistent motion: Do it exactly the same way every time, and the scoop will deliver almost exactly the same charge every time.

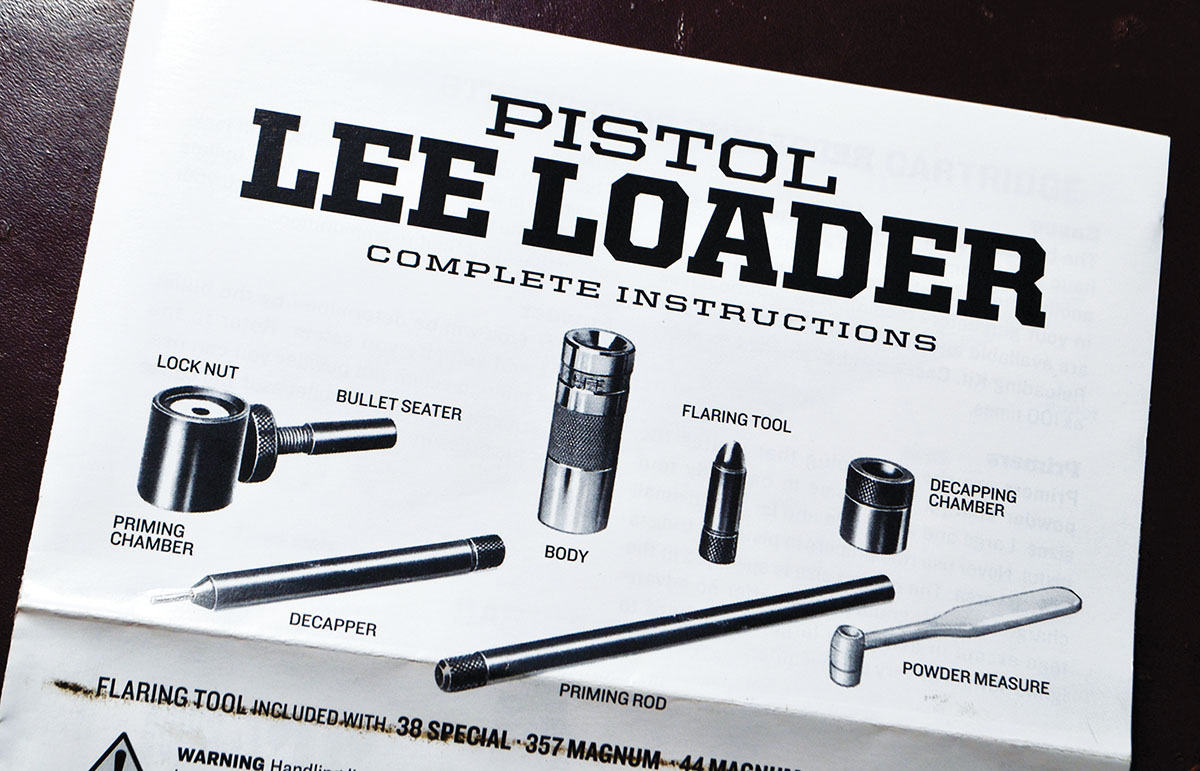

The sequence for reloading a case is as follows: Using a punch and the decapping chamber (a steel cup with a hole in the base) the case is de-primed. It is then resized by tapping it into the sizing die with a mallet or stick of hardwood, then tapped back out of the die with a steel rod, using the decapping chamber as a base. The case is primed in the priming chamber (another steel cup with a spring-loaded platform to accept the primer and allow the case to be tapped down onto it) using the mallet and steel rod.

There are a couple of differences between dies for bottleneck cartridges and straight handgun cases. The bottlenecks are neck-sized only and require no case lubrication; straight cases, like the 38 Special and 45 Colt, are full-length resized and require case lube. As well, these straight revolver cases are provided with a flaring tool, and there is a crimping function incorporated in the other end of the sizing die. (If you’re thinking, “Wow, that Richard Lee thought of everything!” you’re pretty much right.)

I found that with straight cases, especially the 45 Colt, it took a generous amount of case lube and some serious hammering to get it all the way into the sizing die. This, of course, depends a lot on the chambers of your gun. If you do not press it all the way in and resize completely, however, you may find the neck has not been resized sufficiently to grip the bullet.

Not surprisingly, having not used a Lee Loader for the better part of 20 years, it took a little practice to get back into it. Since I was moving to a new house, and my loading bench and tooling were out of operation, it was an opportunity to try the Lee Loader exactly as it would have been used by a newcomer to handloading in the 1950s. Except for using a digital scale to check the charges thrown by the scoops, I used only the tools included with the kits and the same mallet I bought for the purpose in 1975.

The lock nut on the bullet seater tends to come loose in spite of having a rubber washer that is supposed to prevent this. A minor quibble.

It is now 60 years since Lee Precision introduced its loaders for metallic cartridges. In a 1965 Gun Digest, a test article reported it was then available in 68 different calibers, rifle and handgun, as well as the shotshell kits. Today, it is made in far fewer calibers, but includes the obvious ones like 308 Winchester, 38 Special and so on. Occasionally, older ones from years gone by, for more obscure cartridges, appear on eBay or GunBroker.

In the meantime, more sophisticated handloading equipment has appeared and a newcomer can get into the game at a higher level for not much money. Also, Lee Precision itself offers a wide range of loading presses and dies, often at a much lower price than its competitors – fulfilling the goal Richard Lee set for himself in 1950.