The Smith & Wesson Model 610 10mm Auto test revolver includes a frame-mounted firing pin and transfer-bar safety – opposed to the hammer-mounted firing pin of yore. It can be locked with a special key to prevent unauthorized use.

I carried a 44 Magnum through 23 years of guiding/outfitting to avert goat ropes initiated by the occasional client’s nervous glitches and the dicey recoveries that followed. I also used that 44 Magnum to bag all manner of big game, from feral hogs to whitetails to a Boone & Crocket Alaska caribou. In recent years, my 44 Magnum hasn’t seen much action. Today, I prefer a Springfield Armory 1911 Ronin in 10mm Auto for “wilderness” backup.

I won’t waste space here recounting the history of the 10mm Auto, as I have covered that in great depth over the years. Besides, anyone who cares to know this stuff would find that information readily available.

Shown for comparison are: (1) a 9mm Luger +P load, (2) the 10mm Auto under discussion here, (3) 45 ACP, (4) 38 Special, (5) 357 Magnum and (6) 44 Magnum revolver rounds.

The 10mm Auto provides approximately 45 percent less muzzle energy than the 44 magnum but does provide ample kinetic energy for most needs, while also introducing distinct advantages. The 10mm Auto makes a more practical personal defense gun than a magnum wheel gun, and in an autoloading handgun it holds more ammunition. The 10mm is also versatile and substantially more powerful than common pistol rounds such as the 9mm Luger or 45 ACP. The 10mm is also more pleasant to shoot than Remington’s 44 Magnum.

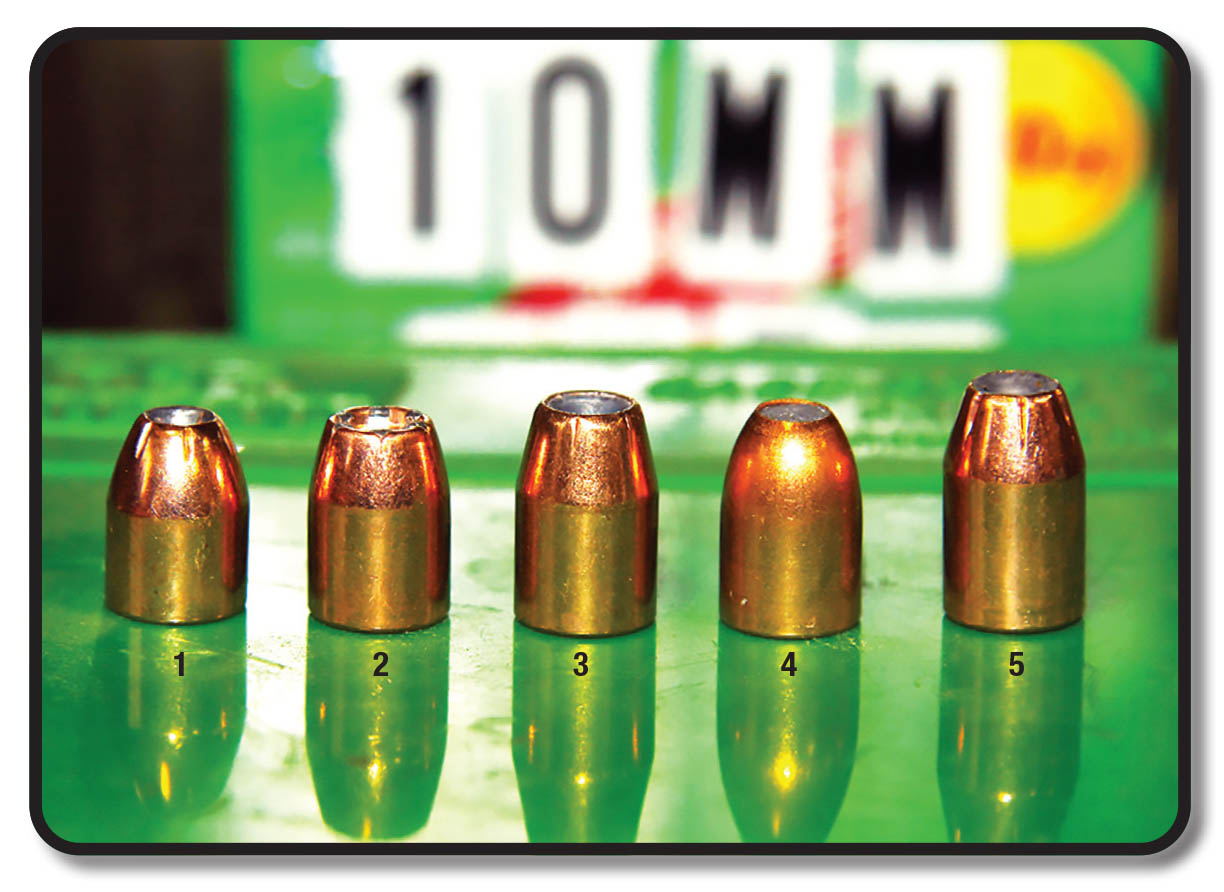

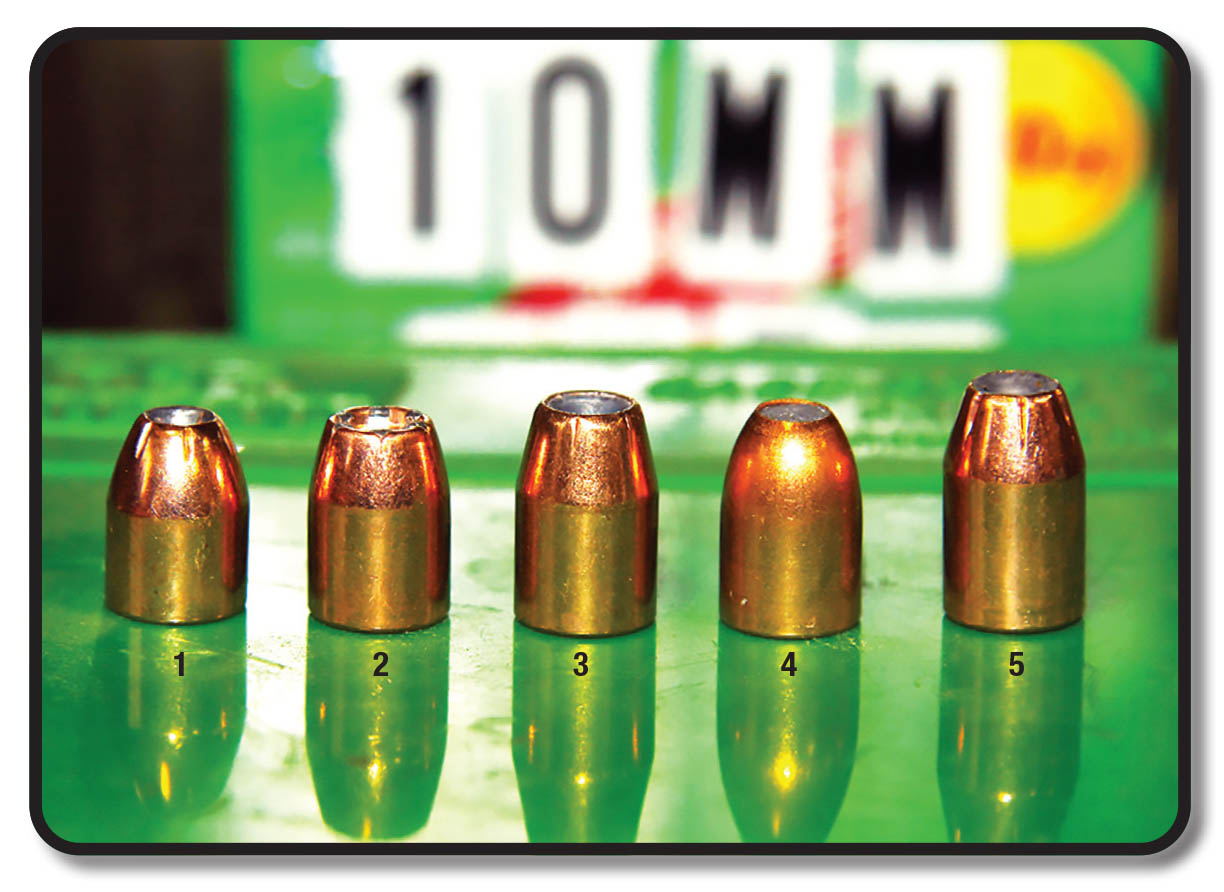

Versatility is accessed through the wide variety of .40/10mm-caliber bullets offered today. Though I’ve never auditioned them in the 10mm Auto, .40-caliber bullets as light as 125 to 135 grains can be found. I believe this powerful cartridge is better served by 155-grain bullets on the light end. The Hornady 155-grain Extreme Terminal Performance (XTP) – found in the accompanying load table – would constitute my personal preservation choice for two-legged hostiles. Speer’s FBI-pedigreed 165-grain Gold Dot (also included in the load table) would likewise offer excellent personal protection. I’ve deployed them quite successfully against sizable feral hogs.

Bullets used for testing included: (1) Hornady 155-grain XTP JHP, (2) Speer 165-grain Gold Dot Plated HP, (3) Sierra 180-grain SportsMaster JHP, (4) Northern Precision 180-grain Round Nose Flat Tip (non-bonded) and (5) Nosler 200-grain ASP JHP.

The original 10mm Auto load, developed by Norma, used a 200-grain bullet, whereas 180-grain bullets have become more popular in modern 10mm loads based on superior velocity and energy delivery. In this round, 180-grain bullets strike an optimum balance. A 180-grain bullet with a G1 ballistic coefficient of .164 and leaving the muzzle at 1,200 feet per second (fps) produces about 624 foot-pounds of kinetic energy. A 200-grain (.199 G1 BC) sent at 1,100 fps produces about 537 foot-pounds. Still, a case is to be made for 200-grain bullets in the “Big Ten.” I have used them to great effect on scads of Texas feral hogs encountered in very tight cover where shot opportunities are better measured in feet instead of yards and where deflections are numerous. That said, in an average stalking or stand scenario, the 180 offers more advantages.

My Ronin 1911 has become part of my uniform while in Texas, helping friends with hog-culling chores or traipsing in local bear habitats. It is a handgun I shoot especially well with, and I’ve worked diligently to develop accurate, task-specific loads around. Though I had no real reason to delve deeper into the 10mm Auto, discovering Smith & Wesson’s Model 610 10mm revolver piqued my curiosity. How would the 61⁄2-inch barrel compare to the 5-inch barrel of my 1911 and closed system affect velocity? Would the heavier revolver offer more effortless accuracy? Perhaps as importantly, would the stout revolver allow wringing a bit more performance from the 10mm cartridge?

Patrick fired all shots by hand from a benchrest using an MTM Case-Gard Predator Shooting Rest. Cold weather required wearing gloves, so some of the larger groups no doubt involved shooter error.

Smith & Wesson’s double-action Model 610 revolver certainly helps make the most of modern 10mm Auto loads. Springfield, Massachusetts-based

Smith & Wesson (S&W) needs no introductions, remaining a revolver mainstay for nearly a century. The Model 610 is built on the company’s big-bore N-frame, the cylinder accepting 10mm Auto as well as lighter 40 S&W ammunition. These rimless rounds require moon clips in the revolver cylinder; three are provided with each handgun.

S&W produced some “Gen-1” 10mm Model 610 revolvers between 1990 and 1992, manufacturing about 4,500 firearms with 5- or 61⁄2-inch barrels and fluted cylinders. In 1998, S&W revisited the Model 610-1, and then the Model 610-2 in 2001, the latter including a distinctive unfluted cylinder and 4-inch barrel. The Model 610 was discontinued shortly afterwards but returned again in the spring of 2019 due to the recent renaissance of the 10mm Auto round.

The test revolver could then be labeled a Model 610-3, representing a hybrid of the models already touched on above. The stainless steel, rubber-gipped revolver can be ordered with a 4- or 61⁄2-inch barrel, the latter chosen for testing here. The design includes a full underlug and a fluted cylinder. The 610’s barrel is one-piece forged, the cylinder release has been redesigned and the hammer and trigger use Metal Injection Molded (MIM) technology. The MIM parts include the look of case-coloring, and the trigger shoe is wide and smooth. Mirroring other recent S&W revolver designs, the new Model 610 includes a frame-mounted firing pin and transfer-bar safety instead of the hammer-mounted firing pin of yore.

The Smith & Wesson Model 610 will shoot 10mm Auto rounds without the provided moon clips but fired cases must then be plucked out one at a time with a fingernail.

The 610 sports an internal lock allowing owners to “switch the revolver off” with the turn of a special key for those with children in the house. I considered the 6 1/2-inch barrel on the test revolver ideal for the accuracy testing I would be conducting and for the hunting that interests me most. In any case, its 50-ounce weight would make it ill-suited as a carry gun. Shooting the 610 in single-action mode, the trigger broke cleanly at about 4 pounds, while the double-action trigger pull was closer to 10 pounds, though it remained impressively smooth.

Though the Model 610 will apparently safely fire 10mm Auto rounds without the provided moon clips (40 S&W rounds require the moon clips for headspacing), I nonetheless used the clips in the hopes that accuracy would be maximized, and because fired cases are then easily extracted using the spring-loaded ejector rod. Without the moon clips, each case must be plucked out individually with a fingernail.

The test handgun was Smith & Wesson’s Model 610, an ergonomic stainless steel, rubber-gipped revolver with 61⁄2-inch barrel. The design includes a full underlug and a fluted cylinder.

I gave each round a standard taper crimp as a separate step to produce proper head spacing. It also aids with consistent and uniform powder burn while helping to lower standard deviations. In short, I loaded all rounds as I would for my 1911 autoloader. Loading the stainless-steel moon clips was best accomplished by laying rounds on a flat surface and pushing the clip openings over the rebated rim until they clicked into place. In general, the loaded moon clips didn’t drop into the cylinder as smoothly as a speed loader, often requiring jiggling to coax all rounds into place.

A Redding Titanium Carbide die set, Federal Champion 300 Large Pistol primers, previously-fired Starline brass and an Aero 419 Zero Reloading Press were used to assemble all loads. Bullets included Hornady’s 155-grain hollowpoint XTP, Speer’s 165-grain Gold Dot hollowpoint, Sierra’s 180-grain Sports Master jacketed hollowpoint (JHP), Northern Precision’s roundnose Flat Tip (non-bonded) and Nosler’s 200-grain Assured Stopping Power (ASP) jacketed hollowpoint. As a hard-core hunter with little interest in plinking, powders were chosen on the promise of top performance and energy delivery – and from what I had on hand. That left out some excellent options – Alliant Power Pistol, Accurate No. 7, and Hodgdon Longshot, for instance – but included Alliant Blue Dot, Herco and 2400, Accurate No. 9, Ramshot Silhouette, Shooters World Ultimate Pistol and Major Pistol and Vihtavuori 3N37.

Patrick used previously-fired Starline brass for all loads. The Smith & Wesson Model 610 required moon clips to shoot the 10mm Auto cartridge, which also allows it to shoot 40 S&W rounds.

As mentioned, I consider the Hornady 155-grain XTP by a self-defense bullet, though I’d imagine it would hold up well on average-sized hogs at close range in a pinch. It certainly offered some serious velocity from the 6 1/2-inch revolver barrel. It includes a skived and protected hollowpoint and a controlled expansion design. It was combined with Alliant Blue Dot and Accurate No. 9. Blue Dot delivered the smallest group with this bullet (.58 inch) using 12 grains of powder. Velocity was also an impressive 1,502 fps. Groups grew larger as more powder was added. Accurate No. 9 produced two sub-MOA groups. Fourteen grains of powder resulted in a .96-inch group at 1,423 fps, while a maximum/compressed load of 15 grains produced a .74-inch group at a hard-hitting 1,513 fps.

Hornady’s 155-grain XTP shot best seated over 12 grains of Alliant Blue Dot, printing three shots into .58-inch and with a muzzle velocity of 1,502 fps.

The Speer 165-grain Gold Dot is a skived hollowpoint designed to meet FBI protocols for penetration and expansion. It includes a lead core and electromagnetically applied copper jacket to produce beautiful mushrooms and maintain high weight retention. The Gold Dot was paired with Shooters World Major Pistol, Accurate No. 9 and Alliant Herco. No. 9 struggled with this bullet, though it did produce a 1.30-inch group at 1,428 fps using 14.5 grains of powder. Major Pistol didn’t produce the extreme group sizes of No. 9, but its best group was just 1.55 inches at 1,380 fps using 11.5 grains of powder. That leaves Herco, which produced the best group with this bullet, measuring .92-inch at 1,384 fps and with a very low extreme velocity spread. Velocity maxed out at 1,494 fps using 9.5 grains of powder and produced a 1.52-inch group.

Sierra’s 180-grain Sports Master JHP has been around for a while, undergoing a handful of refinements over the years to improve terminal performance. This is typically an accurate bullet, making it suitable for target shooting. Accurate No. 9, Vihtavuori 3N37 and Ramshot Silhouette were paired with this one. Vihtavuori 3N37 flailed with this bullet, producing a couple of dismal groups and then redeeming itself with a maximum load of 10 grains. The group measured 1.20 inches at an impressive 1,509 fps. No. 9 also followed that path; two unimpressive groups followed by a .87-inch group sent at 1,433 fps using the maximum/compressed load of 14 grains. In keeping with the maximum-load trend, Silhouette waited until the last load to produce this bullet’s smallest group, .64-inch at 1,387 fps and with a very low extreme velocity spread using 8.5 grains of powder. The Sierra loved the velocity!

Nosler’s 200-grain Assured Stopping Power (ASP) bullet paired best with 9 grains of Alliant Blue Dot, producing the best group of the entire test at .45-inch and with a velocity of 1,234 fps.

Bill Noody, owner of

Northern Precision, made these 180-grain roundnose Flat Tip bullets for a 400 Legend rifle project, but though a relatively pointed bullet the S&W revolver allowed me to utilize them here. Noody also produces bonded versions of this lead-core bullet, which would make a great backup option for bear. I used Alliant 2400, Blue Dot and Shooters World Major Pistol with this bullet. Alliant 2400 produced from impressive velocities without pressure signs – 1,375 to 1,447 fps with 12 to 13 grains of powder – but accuracy proved poor. It shouldn’t be dismissed, as it might fare better with a different bullet. Blue Dot managed 1.05-inch (9 grains, 1,199 fps) and 1.07-inch (11 grains, 1,347 fps) groups with respectable velocities. The easy winner was Major Pistol, producing the .93-inch best group with this bullet, sent at 1,312 fps.

Nosler took the 200-grain slot, providing their excellent ASP JHP. This bullet includes a protected hollowpoint and skiving to ensure consistent expansion. Fueled by Accurate No. 9, Ramshot Silhouette and Alliant Blue Dot, this bullet was responsible for both the very best group of the entire test and some of the worst groups produced. Silhouette faired worst, producing the largest group of the test (nearly 4 inches), but also a 1.32-inch group at 1,202 fps. No. 9 did well overall, producing a .90-inch at 1,277 fps and 1.21-inch group at 1,308 fps using 12 and 12.5 grains of powder. Blue Dot produced two ho-hum groups, but also the test’s .45-inch best, sent at 1,234 fps. That group was produced by 9 grains of powder.

My overall impression of the S&W Model 610 revolver versus my 1911 10mm Auto is a conspicuous increase in felt recoil. Just 1 1/2 inches of extra barrel increased muzzle velocities by 150 to 200 fps on average, sometimes slightly more. That is a fairly significant boost in energy delivery in a hunting or backup situation.

The Model 610 from Smith & Wesson weighs 50 ounces and the trigger broke crisply at 4 pounds in single-action mode. Trigger pull was about 10 pounds when fired double-action, but likewise smooth.

.jpg)