Some foreign references refer to the .45 caliber as the American handgun caliber. This is despite the fact that American .45 caliber handgun barrels have .442-inch bores and .451-inch grooves, making them much closer to .44 than .45 caliber. Caliber has always been defined as bore (land–to–land diameter). Incidentally, riflefolk got it right: .45 caliber rifles have .450-inch bores and .458-inch grooves. Anyone finding this too complicated can wait until the ammunition industry converts to mickey-metric like the optics industry. Then, a box of 45 Auto will be marked 11.455x22.8mm, 14.9 grams. Simple!

Understanding caliber has always been necessary to some degree.

Cowboys, settlers and explorers on the plains of nowhere needed to be certain ammunition for their revolvers would fit and fire reliably, putting a large hole in whatever, or whomever, was currently annoying them.

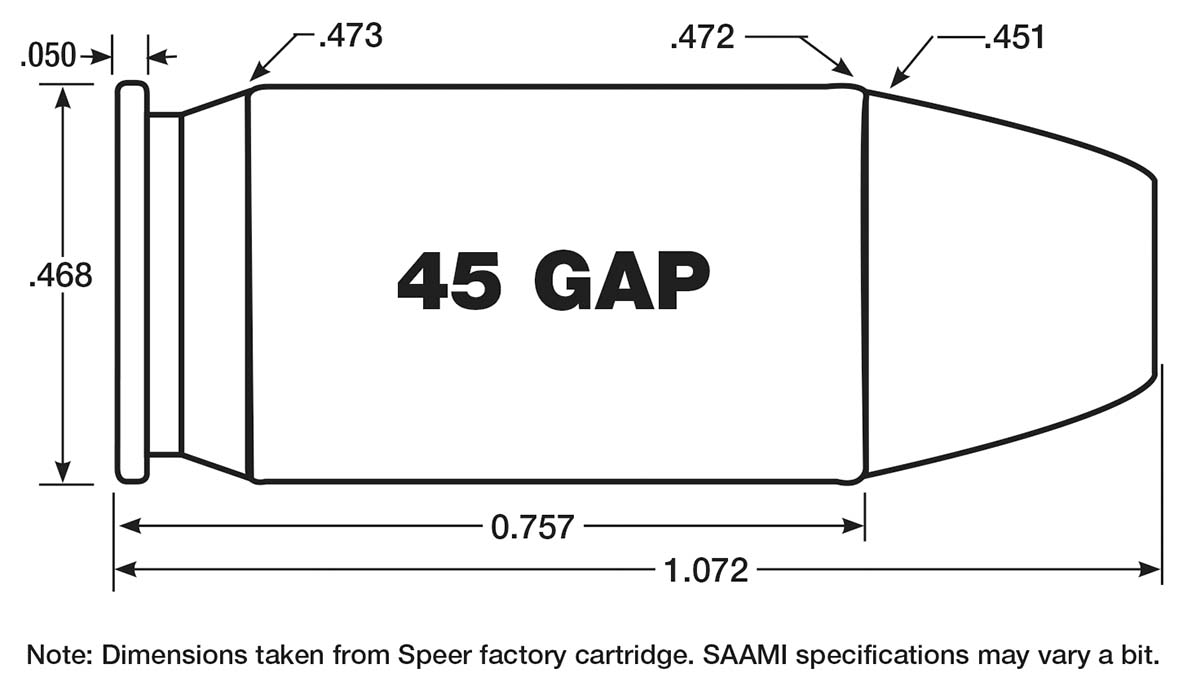

Starline makes cases for those who must handload to keep their 45 GAP shooting.

The first so-called American .45 caliber was the 45 Colt chambered in the Colt SAA of 1873. This may not have been planned because the Army wanted a powerful centerfire revolver badly. Smith & Wesson (S&W) had their No. 3 in 44 American. Colt had the 44 Colt round. Both were outside lubricated. Colt wasn’t worried because its new revolver had a longer cylinder than the S&W and could take a more powerful .44 caliber, if that was what the Army wanted. However, the Army then decided it wanted an inside-lubricated .45 caliber. This caused some excitement at Colt as there was some indication the SAA was scaled for a .44 outside lubed cartridge.

Colt quickly specified an inside-lubed round using a .451 inch diameter bullet, the largest possible in the small cylinder. That left a rim only .030 inch larger in diameter than the case base.

The cartridge was the full length of the cylinder. The Army approved, thus setting .451 inch or so in stone as .45 caliber for the Army. The new 45 Colt cartridge and slightly shortened 45 Colt Government (S&W Schofield length) remained in service until 1892, when the Army adopted the useless Colt Model 1892 double-action revolver firing the equally useless 38 Colt Army cartridge.

With the same overall length, the (1) 9x19mm, (2) 40 S&W and (3) 45 GAP all fit into the same magazine. The (4) 45 ACP is much longer.

The 38 Colt was so underpowered that in 1904, the Army sent two colonels, Louis LaGarde and John Thompson, seven handguns in “calibers” .30 to .476, a couple of buckets of ammunition, and a sergeant to do the shooting at the Chicago Stock Yards. The unlucky targets were a couple of dozen steers, two horses, ten human cadavers and a penguin.

At the conclusion of this circus of gunfire, smoke and plunging terrified animals, Col. LaGarde commented, “. . . a bullet which will have the shock effect and stopping power at short ranges necessary for a military pistol or revolver should have a caliber not less than forty-five.” That was that. John Browning, who was working on a .38 automatic pistol for the government, scrapped the project and told Winchester to come up with a 45 caliber semiautomatic pistol cartridge.

Someone at Winchester shortened the 30-03 Winchester rifle round to .900 inch, thinned the case walls, seated a 230-grain cupronickel jacketed bullet, and called the job done. Velocity was around 800 feet per second (fps). Browning perfected the Model 19II pistol, and the rest is history.

This lineup includes: (1) a 30-03 case, (2) an early 45 ACP using the 30-03 extractor groove dimensions, (3) a modern 45 ACP with current extractor groove and (4) a 45 GAP, which appears to have gone back to its original form.

As time went by, the 45 Automatic Colt Pistol (ACP) attracted quite a following. Close-range encounters were its forte. Eventually, Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) was set at 21,000 pounds per square inch (psi transducer). Of course, there was soon a +P pressure set at 23, 000 psi. These pressures gave 230-grain bullets at about 850 seconds and 950 fps, respectively.

Then something strange happened. The chronicles tell us that Glock, a supplier of semiautomatic pistols to much of law enforcement in the U.S., detected a desire for a new handgun. This was to be of .45 caliber, duplicate 45 ACP power and have a double stack magazine. With a frame and slide the same size as a 9mm! That was all!

The .45s used in American revolvers: (1) English .450, (2) 45 Webley, (3) 45 Colt, (4) 45 ACP, (5) 45 Auto Rim and (6) 454 Casull.

Actually, the cartridge was not too much of a problem. Glock partnered with Speer/ATK to develop it. With that type of support, most anything is possible, so long as you are sure of what you want. A .45 caliber with a 10-round magazine in a 9mm package should have caused a rethinking of the situation.

The obvious place to begin was shortening the 45 ACP round to 9mm/40 S&W length. When this was done, it was discovered that due to their thickening to form the web of the case, 230-grain bullets could not be seated without bulging case walls. When new cases were drawn, 45 ACP ballistics could not be obtained unless pressure was raised to the 45 ACP +P level of 23,000 psi. Surprise? Even then, bullet weight was limited to 200 grains. The 45 Glock Automatic Pistol (GAP) cartridge was born. Its pistol was the Glock 37, identical sizewise to the 9mm Glock 19. Full 45 ACP velocities with 230-grain bullets would come quickly.

American 45 Auto cartridges are: (1) 45 ACP, (2) 45 GAP and the largely forgotten (3) 45 Winchester Magnum.

The first factory loads came from Federal in 2004. They were 185-grain full metal jacket and 185-grain Hydra-Shok bullets, both achieving 1,090 fps from a 5-inch test barrel. Sounds a bit like a 40 S&W. That same year, Winchester offered a 185-grain Silvertip hollowpoint at 1,000 fps and three, 230-grain slugs – a full metal jacket listed at 850 fps, a jacketed hollowpoint listed at 880 fps and WinClean having a full metal jacket bullet with brass enclosed base at 875 fps – all from 5-inch barrels.

Within a few years, factory rounds numbered eighteen. Ten of those used bullets ranging from 160 to 200 grains, the same bullets used in the 45 ACP, and at the same velocities. The same for eight 230 grainers. Same bullets, same velocities (850 - 875 fps) as standard pressure (non +P) 45 ACP loads. The situation was not perfect. The problem was not the ammunition. It performed exactly as Glock wanted. The problem was the gun. The original idea was to chamber the 45 GAP in a pistol of exactly the same size as the 9mm Glock 17. This turned out to be impossible because the new round began damaging Glock 17-size frames. Weight was added by making the slide wider. This required an extended slide release. These changes meant the Glock 37 would no longer fit Glock 17 holsters. Not good for departments having hundreds of such holsters in inventory.

The 45 ACP (left) uses large pistol primers, the 45 GAP (right) is fitted with small pistol primers. however, some 45 ACP brass will utilize small pistol primers.

Then there was the magazine. Having the same dimensions as the 9mm Glock 17, but with modified feed lips for the larger diameter 45 GAP round, getting ten rounds in the box was just a tad short of impossible for most folks. Loading nine or even eight was common. If ten rounds were forced into the magazine, the spring totally collapsed. There was no space to push down further when snapping a full magazine into a gun with the slide forward! A couple of reviewers mentioned turning the gun upside down on the ground, dropping it in the magazine, and then standing on it until it clicked into place. This was probably hard on the sights. Hardly a fast tactical reload.

A plug gauge in the bore of a 45 Colt shows .442 inch – essentially a .44 caliber. Thus began from 1873, a new definition of .45 caliber for U.S handguns.

Of course there was still what happened when the trigger was pulled: the lighter weight, smaller-sized gun kicked harder than a 45 ACP. Qualification was harder. Other annoying problems surfaced as well. It’s bad enough fighting a dangerous situation without having to fight a gun as well. Eventually, sales dropped off until, and while some police departments still use it, the 45 GAP is considered dead.

Used guns will be available for a while, reloading dies are listed, and good ol’ Starline makes quality cases so handloaders can always make ammunition. The 45 GAP was an engineering exercise that was way too specialized for virtually everyone. It’s hard to believe it got as far as it did. It will probably be the last new American 45 automatic.

.jpg)