In Range

Data, Knowledge and Wisdom

column By: Terry Wieland | June, 25

To be blunt, I found Dr. Brownell’s writings almost impenetrable. Limited as to space, he preferred to publish yet another incomprehensible block of equations rather than summarize his conclusions in a paragraph of plain English.

Determined to try, however, I forced myself to read each section of the book and try to figure out what was what; and there, like a small plum in a large pudding, I found a nugget of information that has stuck with me ever since.

In one experiment, Dr. Brownell found something inexplicable. A 105-grain roundnose Speer bullet, in an otherwise perfectly safe load with similar bullets of the same weight, delivered seriously dangerous pressures. This happened every time, to the point that Dr. Brownell inserted a warning against mixing the 105 Speer with anything resembling it.

Baffled, he made several trips to the Speer factory in Lewiston, Idaho, to consult with Speer’s ballisticians. They finally concluded that the anomaly was due to the jacket material combined with long parallel jacket walls that gripped the bore tightly.

I mention this not to warn specifically about the bullet, which was still being made in 1987, when the Speer Reloading Manual Number 11 was published, but was gone a decade later, according to the Speer Reloading Manual Number 13. Earlier Speer manuals stated the 105 roundnose was created specifically for the 244 Remington, whose 1:12-inch twist would not stabilize the longer 105-grain spitzer. (For the record, the 105 roundnose catalog number was Number 1223, should you happen across a box.)

Information about the whole affair is sketchy, and to the best of my knowledge, no other warnings have ever been published. I mention all this to illustrate the value not only of accurate data and reliable information but also the need for caution and always playing it safe.

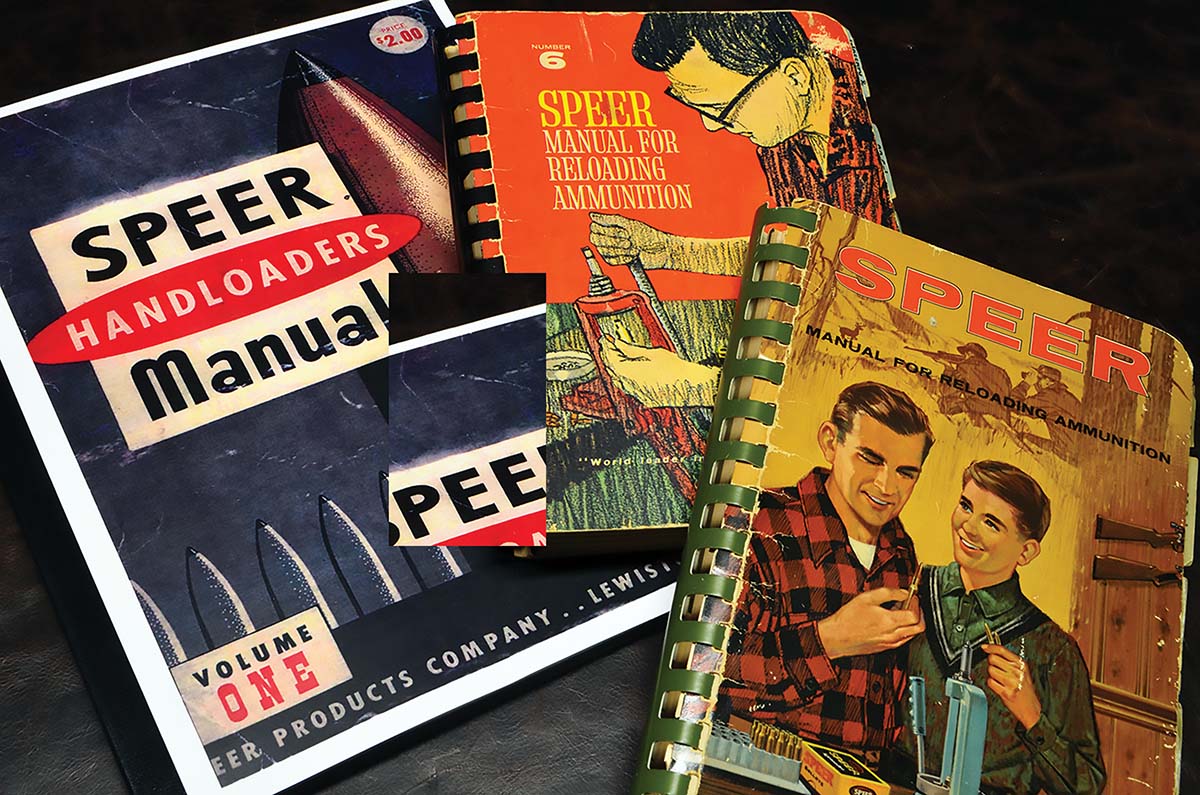

Speer has been publishing loading manuals since 1956, when the Speer Handloaders Manual Volume One came on the scene, and over the years have proven to be among the best. For a long time, all you could get were the Lyman and Speer books, until the 1980s when every bullet and powder manufacturer, it seemed, felt they needed one.

Most of these are oriented toward the company’s own products, but Lyman and Speer have always taken a more catholic approach, which is why Speer is the one I generally consult unless I have good reason to look elsewhere.

I don’t have every edition, only numbers 1, 6, 7, 11, 13, 14 and 15, which is the latest. As new books come out with additional information and new cartridges, older material is inevitably dropped.

For example, my feature article in this issue is about the 22 Savage Hi-Power, which was introduced around 1911 and dropped from just about everyone’s cartridge line by 1990. To find load data of any kind, I had to consult some very old manuals.

However, it is not just data for obsolescent cartridges that fall by the wayside. Often, bits of information that could be vital if you knew them are mentioned once and then forgotten.

Twenty years ago, working with a custom 22 K-Hornet on a Martini action, I pulled the trigger on what should have been a perfectly safe load and locked up the action to the point where it required a gunsmith. It was a British Martini 22 rimfire action that had been converted – badly – and was a problem waiting to happen. The action was so sufficiently damaged that over the next 15 years, it visited four different gunsmiths, each with a different solution until finally, Lee Shaver took it on and resolved it once and for all.

What I didn’t know at the time was that around 1950 brass makers redesigned the Hornet case to make it stronger. Thicker walls reduced case capacity, which caused excessive pressures with what would previously have been safe loads. Philip B. Sharpe’s Complete Guide to Handloading (Third Edition, Second Revision, 1953), in its supplement, carried a warning about this change, but the load data in the earlier part of the book remained unchanged. Not having seen the warning, it was there that I got the data that proved hazardous. Thanks, Phil.

Dean Grennell, long-time editor of Gun World and author of several books on handloading, referred to publications before about 1975 as the “intrepid” manuals because their recommended loads were much hotter than those found in later editions. In most cases, this was due to a switch to pressure barrels rather than actual rifles, coupled with more sophisticated measuring techniques and an explosion of product-liability suits in the U.S.

Look in an older Speer manual, and with each cartridge, you will see the rifle in which it was tested. Later, you will find details on the pressure barrel instead. Since rifles vary, even among the same model from the same manufacturer, it’s obvious why every manual warns users to start low and work up rather than begin with a load marked “maximum.”

Older powder designations can be a problem, too. Early manuals mentioned powders such as 4831, 4895 and 4350 without specifying the manufacturer for the simple reason that, at the time, there was only one. Both 4831 and 4895 were surplus powders sold by Hodgdon, and the IMR equivalents came along later; the same was true, in reverse, of 4350. None of these – none! – are interchangeable, load for load.

Speaking of H-4895, one of the all-time great rifle powders, the first Speer manual (1956) carries a warning. Bruce Hodgdon got into the business after the war when he purchased a load of government surplus 30-06 powder. It was made by Du Pont (IMR). When that ran out, Hodgdon found some more, but there were slight variations in the burning rate. The Speer manual assured us that any powder shipped since 1952 was from a blended lot to ensure uniform burning rates. In a lifetime of reading everything I can find on this stuff, I’d never heard that.

Brass? A couple of years ago I was working with a 270 Winchester and decided to try some very old “Pet Loads.” In the early issues of Handloader, the editor elicited pet loads from prominent shooters. In the case of the 270, it was Jack O’Connor.

I wanted to try the load O’Connor had used all over the world, to great and glorious effect and found I could not physically get it all into a case, much less seat a bullet. I knew O’Connor liked them hot, and was from a buccaneering age, but still. I then found a 270 case from the 1960s and compared its capacity with a new one from the same company. There was a significant difference in capacity and even more with other brands.

This is not surprising since machinery wears out and is replaced, and brass from the new machine, while still meeting SAAMI standards, may differ from the old.

Warnings? I know of none, which doesn’t mean there weren’t any. You can’t read everything published, and it’s up to the individual – in this case, me – to take precautions.

By the way, I tried to get as close as I could to O’Connor’s pet load and it was, in my rifle, nothing to write home about for either velocity or accuracy. Still, it was a learning experience.

When working with cartridges that were obsolete when Eisenhower was president, older manuals are essential, and as many as you can get. Cornell Publications can provide Speer Handloaders Manual Volume One as a reprint, and many of the later editions can be found online at eBay or Amazon. I particularly recommend Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition Number 6 (1964) which includes articles by O’Connor, Grennell, Hodgdon himself on powders, Warren Page, Pete Brown, Kent Bellah, Bob Steindler, Capt. George Nonte (he of the waxed mustache) and Francis Sell.

All are worth reading and there is always more to learn, as even Lloyd Brownell, Ph.D., discovered.