It offers fast shouldering and effortless swinging on fast-fleeing quarry, as well as nearly identical downrange performance of the 12 gauge. Such attributes also enable it to perform well on the sporting clays course.

Frequently, shooters and hunters select a particular firearm and/or cartridge to be different. After all, why use what your compadre does, or is currently in vogue, right? But sometimes, the choice has more to do with fitting a specific set of criteria rather than being an individualist. Such is the case with aficionados of the 16 gauge.

Aaron evaluated the 16-gauge handloads using a Stevens 555E over-under shotgun equipped with factory, flush-fitting modified and improved-modified choke tubes. As can be expected, high-velocity 11⁄8-ounce and heavier loads produced noteworthy perceived recoil in the 6.45-pound shotgun.

“All too many shotgunners and manufacturers regard the 16-gauge shotgun as something of a novelty,” explained Ballistic Products Incorporated’s (BPI)

The 16-Gauge Manual, 6th Edition. “Those who know and love the 16-gauge know well the ‘sweet’ 16’s performance benefits and handling characteristics. The reason for this [Germany’s] devotion is mainly due to the 16-gauge’s unique niche and capabilities.” What are those? Read on.

History & Role

Of the prevailing gauges, the sixteen’s origins are among the least known and coherent. According to Cartridges of the World, 13th Edition, “In 1866, a rebated-rim, reloadable-steel, 16-gauge shell was patented by Thomas L. Sturtevant. Revolving magazine, four-shot guns chambered for this shell were offered by the Roper Sporting Arms Company, until the early 1880s.” Brief, I know. The above mentioned BPI manual details, “In Germany, where the 16 was first developed and given an identity … .” Regardless of its exact origin story, though, the 16 gauge is not a here today, gone tomorrow cartridge. It’s time-tested and still employed in the U.S., albeit to a lesser scale than in Europe, where it remains well-liked. In the past couple decades, the 16 gauge has experienced an uptick in admiration in the U.S. Still, its acceptance falls well short of the two gauges that bracket it, the 12 and the 20. Why?

Unsurprisingly, since the number of 16-gauge shooters is proportionally much smaller than those wielding a 12 or 20 gauge, fewer target/field wads are available for handloading the overlooked gauge. Still, excellent options exist including: Claybuster CB0100-16, BPI Z16 and BPI SG16.

Hunters in the U.S. like to discuss the one-gun solution for rifles ad nauseam but practice it for shotguns. Also, since the ubiquitous 12 gauge handles nigh on all shotgunning tasks, despite not being the best choice for each one, it’s often selected. This also applies to the 3-inch 20 gauge, which has further eroded interest in the superior 16 gauge. Flexibility wins the day.

“The post-World War II demands for the 12-gauge shotgun forced long-lasting, unbreakable habits of production and marketing into American ammunition manufacturers,” explains BPI’s guidebook. “Shooters didn’t have many options in the years following World War II; therefore, ammunition offerings were mainly confined to the shotguns that were available. [Since they’re employed for the same tasks], the 16-gauge competes head-to-head with the well-established 12 gauge for general shooting applications.” In addition, since less development is dedicated to 16-gauge loads, and their cost is exponentially more – not to mention that fewer 16-gauge shotguns are available – and we recognize the vicious cycle in which the 16 gauge is trapped. As you’ll see, it shouldn’t be this way.

Specifications & Capabilities

BPI’s dual-petal SG16 is incredibly versatile, as well as unique. The pins in the gas seal lift it above the propellant, thereby enabling it to work with a wider selection of them.

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) set the 2¾-inch 16 gauge’s maximum average pressure at 11,500 pounds per square inch (psi), the same as the 2¾- and 3-inch 12 gauge. The bore diameter is .665 inch +0.020 inch, placing it nicely between those of the 12 and 20 gauge. The 16 gauge isn’t available in 3 inch, and it doesn’t need to be. For its missions, it works masterfully as it is. Factory payloads of lead-alloy shot range from 1 to 1 1⁄8 ounce, with the latter being considered a “magnum load” as would be expected, steel shot charges are somewhat lighter. Only turkey loads featuring TSS exceed this. For instance, Apex Ammunition features 15⁄8 ounces of tungsten-based shot. Most shotshells are dedicated to upland hunting for a reason.

The ability of the 16 gauge to surpass 1,400 feet per second (fps) with a 11⁄8 ounce load is nothing special as the 12 gauge can easily equal such performance. It’s that faculty in a light, nimble shotgun that endears the obscure gauge to wing shooters. In a well-designed, scaled-down scattergun, the 16 gauge is delightful to carry for long jaunts, be it sidehilling for chukar, crossing ceaseless Conservation Reserve Program fields for pheasants, or navigating tangled laurel thickets for ruffed grouse. When the opportunity presents itself, the 16 gauge has every bit the capability of the 2¾-inch 12 gauge. That’s why shooters in the know select it. It’s unequaled for upland hunting.

For the loads accompanying this article, Aaron selected the most prevalent and highest-quality hulls that include (left to right): Fiocchi, Cheddite and Federal.

New, primed 16-gauge hulls sold as components for handloaders are available from Cheddite and Fiocchi. Sold in 100-count packages, the durable and versatile hulls are the optimal foundation for high-performance handloads.

As of this writing, online retailer MidwayUSA lists 14 lines of lead-base, upland-suitable, 16-gauge shells. There are more if you consider the various shot sizes available in each. Sprinkle in a few lead-free options and that’s all. Additionally, only 1- and 1 1⁄8-ounce lead loads are available, although those will work for all upland species, furred or feathered. But they’re expensive – even the target loads that can pull double-duty for small quarry retail for $17 or more per box, which approaches double that of the 12 gauge. Premium or magnum loads are around $30 per 25. For these reasons, as well as general availability, handloading the 16 gauge is wise.

Handloading the 16 Gauge

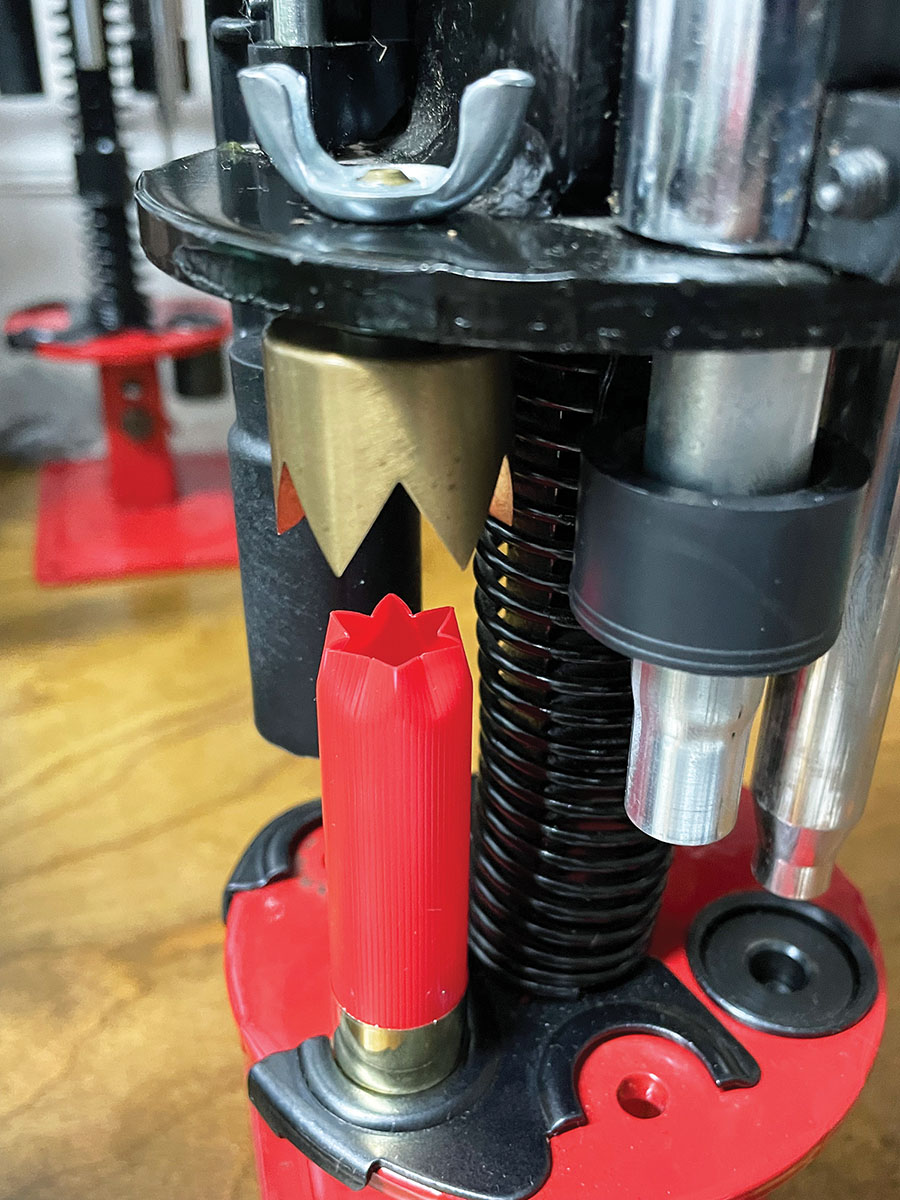

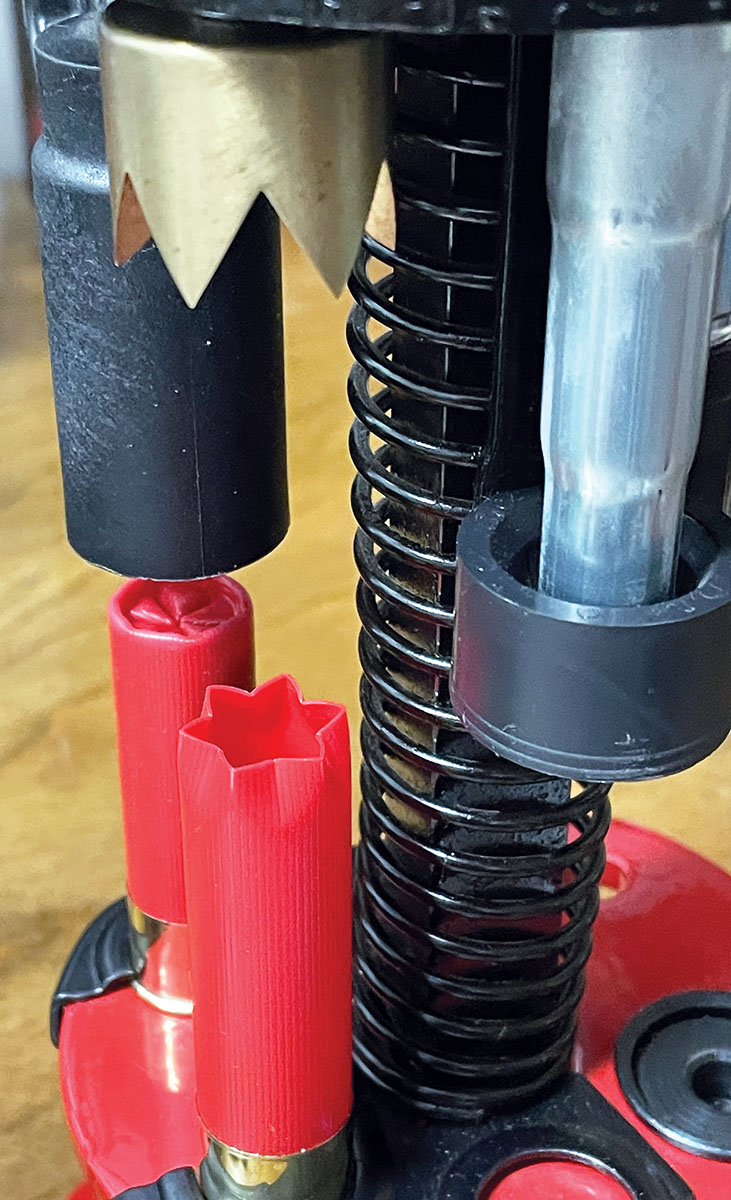

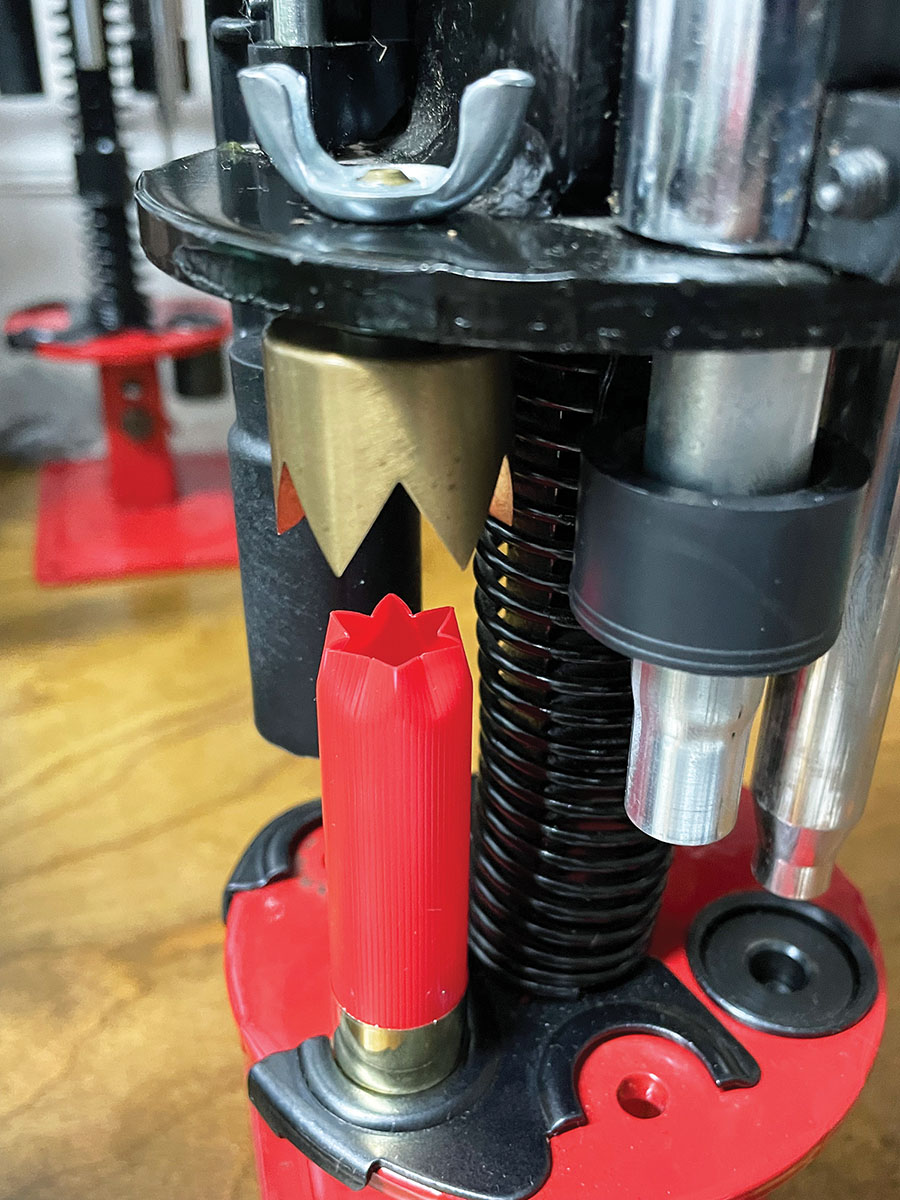

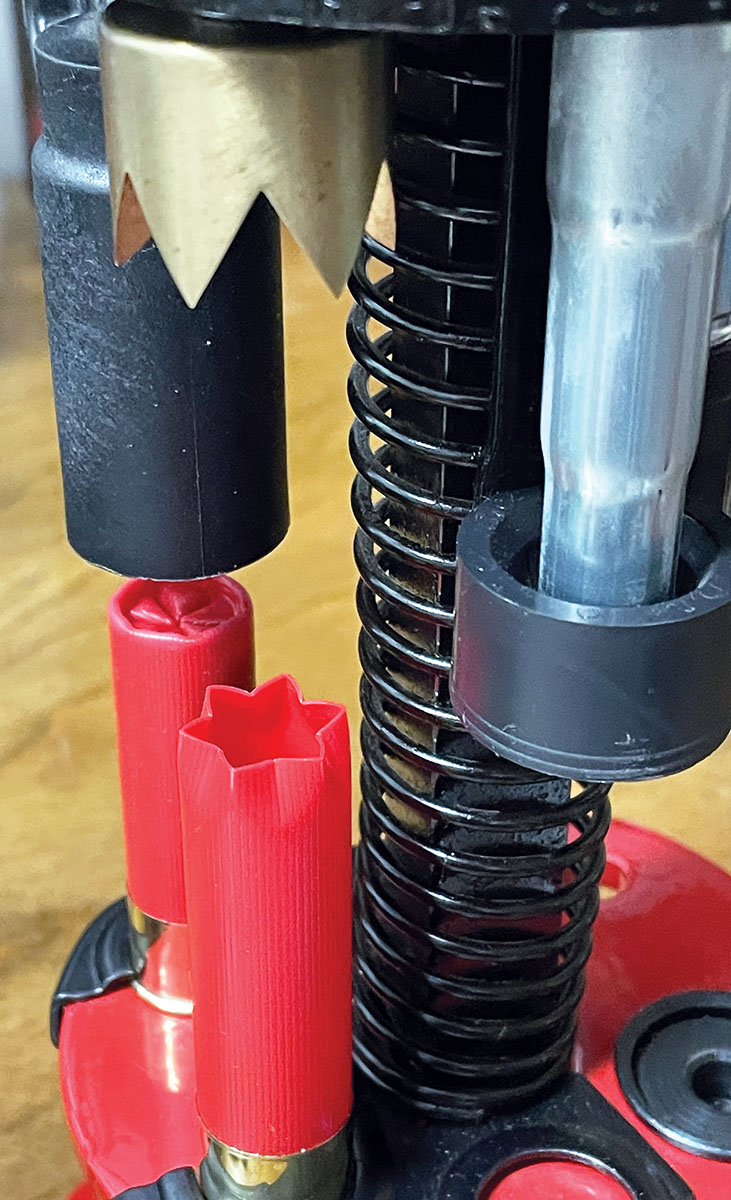

Unless you’re an ardent upland hunter, practice devotedly, or press your 16 gauge in registered skeet or sporting clays tournaments, which I have done successfully, a single-stage press is likely all that is needed for handloading. I opted for the uncomplicated, time-tested MEC 600 Jr., Mark V. As is often the case, I swapped the factory-installed Spindex Star Crimp with a BPI Super Crown Crimp Starter (large bore, six point). Why? While you’ll have your once-fired hulls and can occasionally scrounge some from shotgun ranges (double-check these for quality, though), you’ll likely use new, primed hulls and the BPI unit does a superior job in creating consistent crimps with staying power.

Although non-plated lead-alloy shot works well for furred and feathered upland game, it’s inferior to nickel- and copper- plated shot for the task. Plated shot produces denser patterns and penetrates deeper, both of which are desirable for escaping game.

Utilitarian, straight-walled Fiocchi and Cheddite hulls are generally available from BPI and other sources. These are pre-primed with Fiocchi 616 and Cheddite 209 primers, respectively. One hundred hulls will cost around $19. Considering the value of the primers, let alone loaded 16-gauge ammunition nowadays, it’s a solid deal. The hulls also have significant internal capacity, making them capable of handling a wide range of loads. They’re long-lasting too. The hulls from Federal’s Game Loads (with paper base) are also good for a cycle or two of reloading.

If you’re using the European hulls, be sure to have matching primers on hand due to the size difference between them and domestically produced primers. A loose fit can result in lost performance or make a semiautomatic firearm inoperable due to a rogue, loose primer.

The greatest load diversity is offered by straight-walled hulls, such as these from Cheddite. Given the correct components, they’ll handle everything from low-recoil target loads up to those pattern-filling, hard-hitting magnums.

Propellants that are advantageous to the 16 gauge are the same as those that can be employed in 12-gauge heavy target and hunting loads. Options abound, too. Among the best for light (5⁄8, ¾ and 7⁄8 ounce) to standard (1, 11⁄16 and 11⁄8) loads are: Alliant Green Dot, Herco, 20/28, E3, Unique and Pro Reach; Hodgdon HS-6, International, Universal, Clays, Longshot and Hi-Skor 800-X (discontinued); and Winchester WST. Some offer more flexibility than others. To propel payloads 1¼ ounces or heavier, Alliant Steel and Blue Dot, as well as Hodgdon Lil’Gun and Longshot get the nod. My favorites include Alliant Green Dot, 20/28, Herco, Hodgdon Universal and Longshot. These give me a range of velocities and duplicating 1,165 fps factory 1-ounce loads is easy, as is surpassing 1,400 fps with 1- and 11⁄8-ounce shot charges.

As with other uncelebrated gauges, wads for the sixteen are limited in selection. However, despite the lack of diversity, you can find what you need. This is particularly true for upland hunting, practice at the clays course and competition. BPI sells two of the best options, the SG16 (and SG16S short sibling) as well as the Field Commander Z16.

Not all shot sizes are a good fit for the 16 gauge. The best options, particularly for upland hunting, are found between – and including – No. 8 and No. 5. Shown here are (left to right): No. 8, No. 7½, No. 6 and No. 5.

My preference for across-the-board use is the SG16. The distinctive wad has a gas seal featuring 24 pins around a central one that lifts it above the propellant charge, thereby making it fit better with a range of propellants and payloads. Its forte is 7⁄8- to 1-ounce loads. Moreover, it has a G-ring crush section and tear-away petals, the latter of which can be removed. Why? If so desired, the petal-less SG16 can be combined with an X-Stream spreader insert to foster rapid shot dispersion for fast, close-flushing quarry.

Thanks to its distinctive crush section, the Z16 will accommodate 7⁄8- to 1¼-ounce payloads. Light loads often require a filler wad, such as cork or felt, thereby increasing cost. The 1.50-inch wad has an arched dome gas seal, as well as four thick petals. The latter increases constriction when traversing the choke, resulting in denser patterns and greater effective range. Truth be told, both wads will suffice for all ethical shots on upland game.

Wads from domestic ammunition makers cannot be found; the same is true with the 410. Fortunately, the Claybuster makes an excellent clone of the vaunted WAA16. An economical replica, the four-petal CB0100-16 wad is good for 1- to 1 1⁄8-ounce loads in a variety of hulls. Its sibling, the CB0078-16, also a four-petal design, was created for low-recoil 7⁄8-ounce loads that could multitask for dove, quail and other small birds, as well as squirrels and rabbits.

Given that factory 16-gauge shotshells are few in number, and even less are good candidates for reloading, new, primed hulls will be the foundation for most handloads. To ensure a satisfactory, factory-like crimp, Aaron recommends adding a BPI Super Crown Crimp Starter to your press.

Quality crimps demand attention to detail in component selection and equipment. The addition of BPI’s Super Crown Crimp Starter to a MEC 600 Jr., Mark V single-stage press is a perfect example. Note that the non-crimped hull was placed there for illustration purposes.

There are several 16-gauge wads capable of withstanding the rigors of extra-hard, non-lead shot. However, since this article focuses on lead loads, I’ll omit them here. For more information on them, you can visit ballisticproducts.com.

The shot selection for the 16 gauge isn’t so straightforward. Upland game varies greatly in size, and the environment in which they’ll be encountered in differs considerably. Know that due to the 16 gauge’s reduced capacity (when compared to the 12 gauge), it works best with No. 8 to No. 4 shot. For most upland species, No. 7½, 6½ or 6 shot are the best choices. This is due to sufficient pellet quantities being found within 1- to 1 1⁄8-ounce payloads and the pellets will have adequate energy remaining to down game at ethical shot distances. Nickel- or copper-plated lead shot is preferable due to its increased penetration and improved patterns.

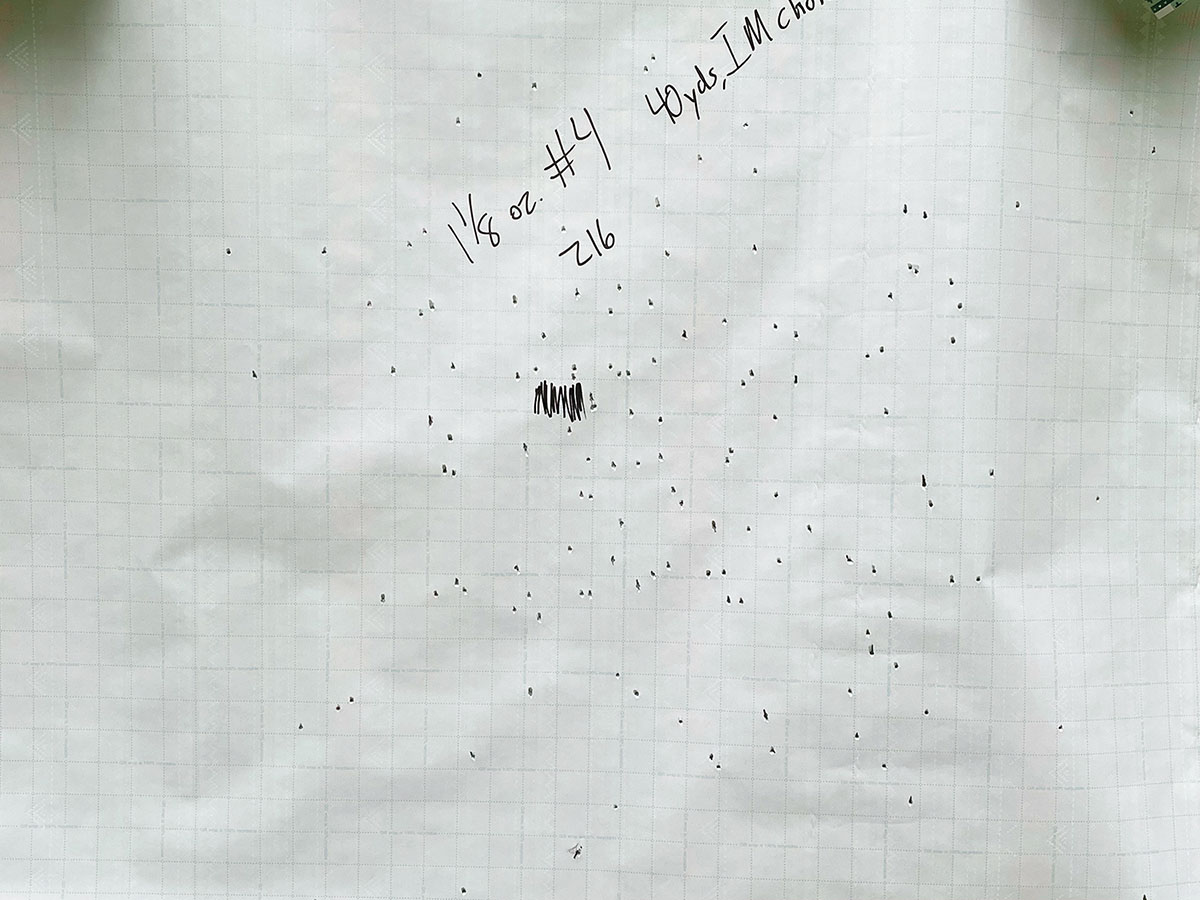

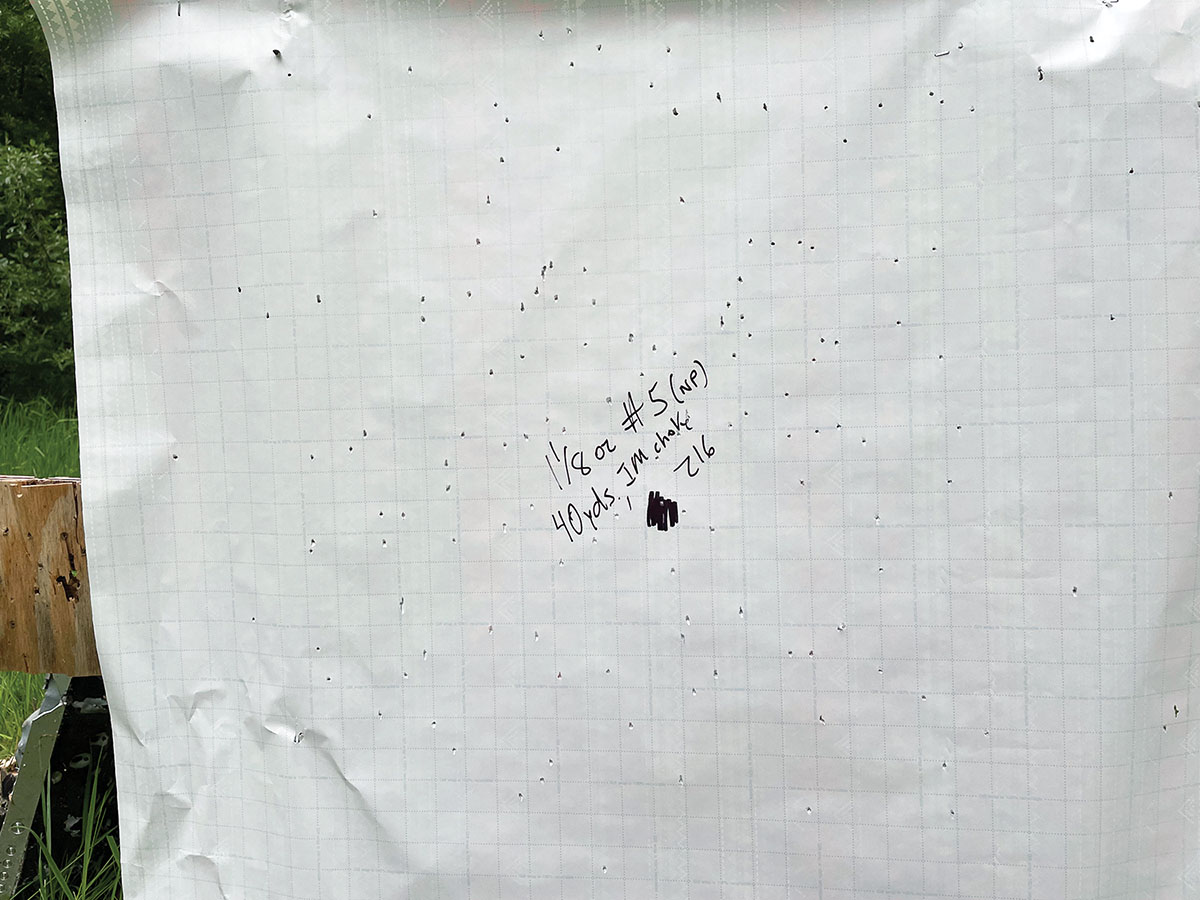

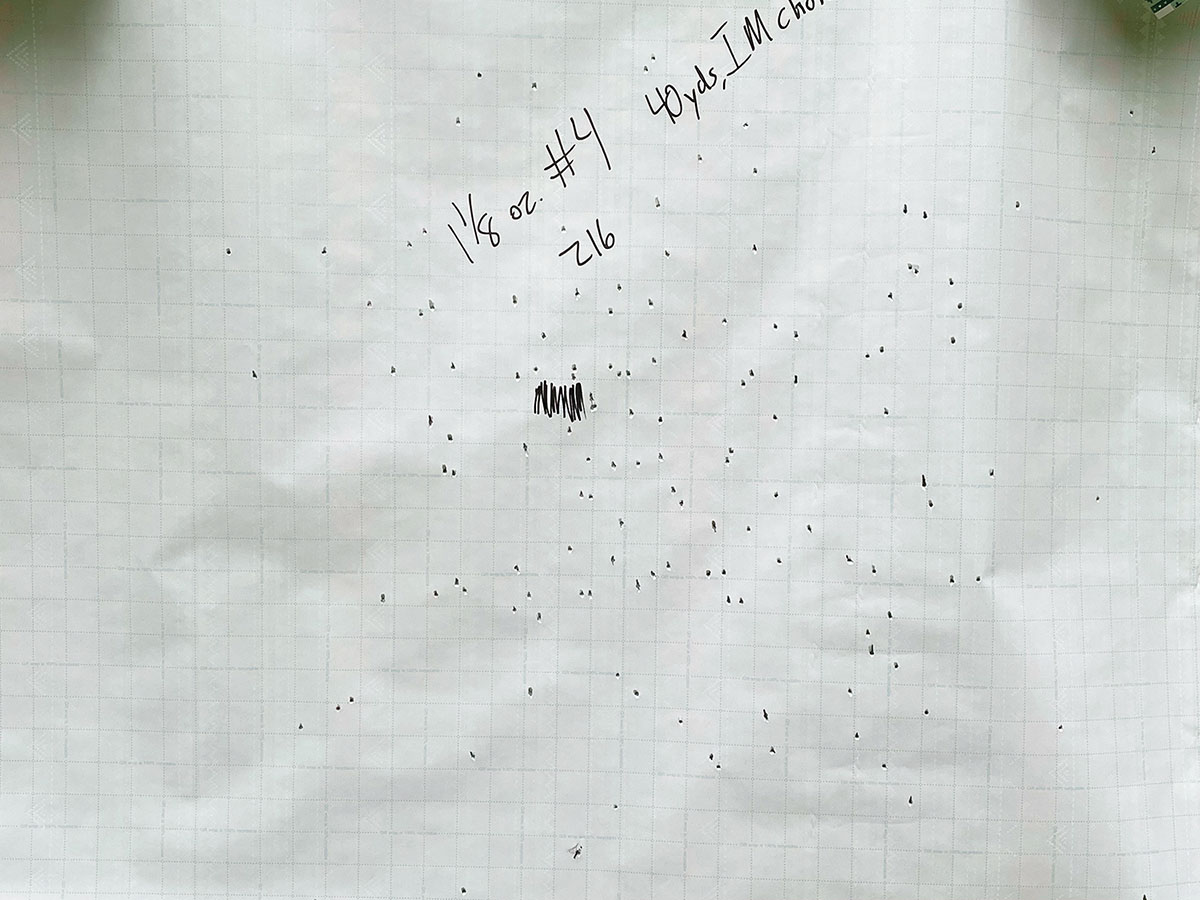

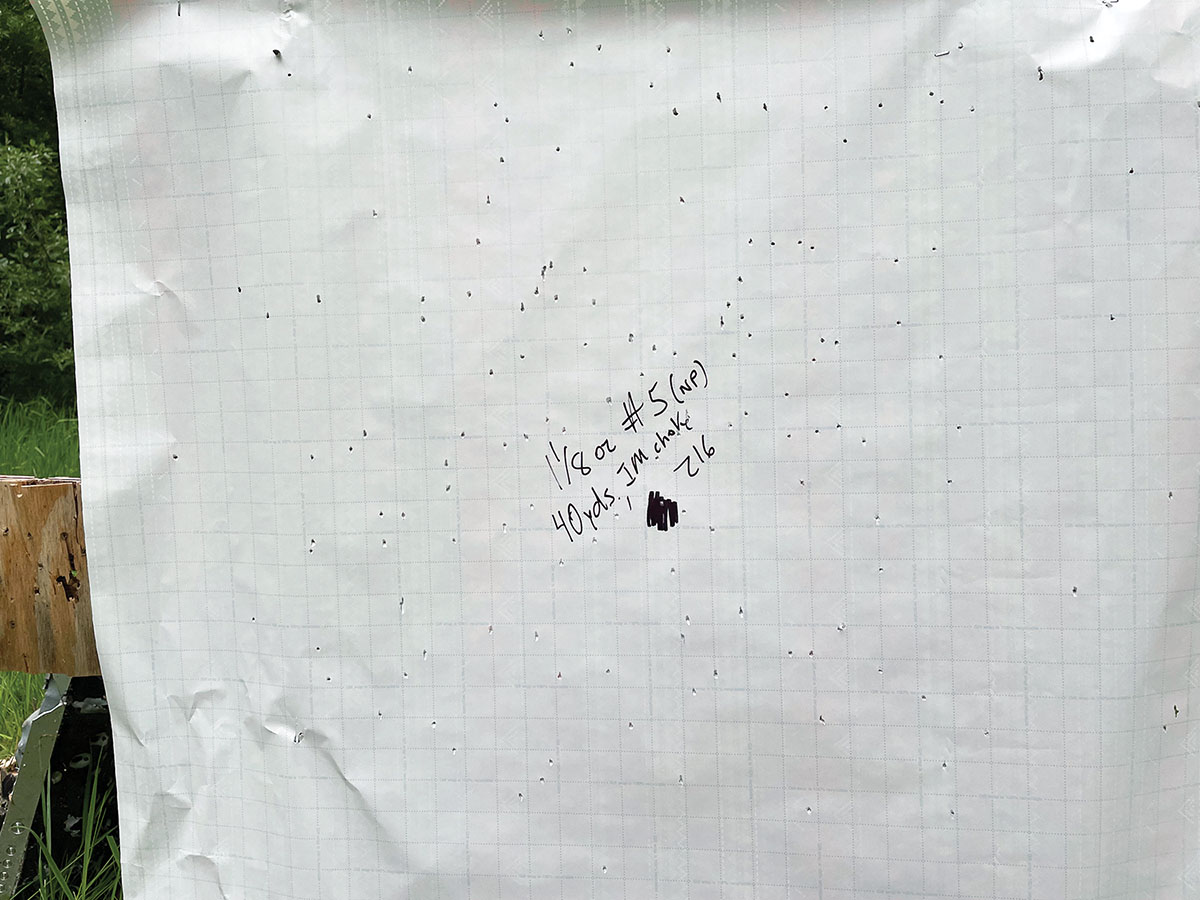

When hunting larger species of grouse and/or pheasants, particularly the latter later in the season, upsizing to No. 5½, 5 or 4 shot is a sensible decision. A 11⁄8-ounce payload of No. 5 nickel-plated shot contains 191 pellets, while the same weight of No. 5½ contains 226. Conversely, the same weight of No. 4s, which is often utilized when hunting larger gamebirds, only has 151 pellets. If 1 ounce is selected, that equates to 134 pellets. For comparison sake, 170 and 201 pellets No. 5 and 5½, respectively, are contained in a 1-ounce shot charge. Generally, the larger the shot, the tighter the pattern compared to smaller shot, and through the right choke, 1 1⁄8-ounces of No. 4s can create very dense patterns at distance. Shot size is a matter of personal preference. I do recommend patterning the load(s) to evaluate performance before heading afield.

The 16 gauge is equally as capable as the 12 gauge on the sporting clays course and for upland species. When practicing, though, it’s advisable to use loads featuring 1 ounce or less of shot propelled to moderate velocities, as the cumulative effects of magnum-like loads is counterproductive to building wing-shooting skills.

Given the wide variance of payloads that the 16 gauge is capable of handling, as well as the diversity of propellant designs, it makes sense that no wad is ideally suited for every combination. Many of the loads found in the accompanying table have overshot cards. If a larger pellet size is selected, these may occupy too much room for a solid, reliable crimp. In such cases, they can be omitted without detriment. Otherwise, the load must be followed exactly. I encountered little of this while assembling those loads for this article. Most were loaded with magnum-lead No. 7½ shot, though some featured plated and non-plated No. 6s, 5s and 4s for patterning.

Whereas a 1 1⁄8-ounce load is considered a heavy target or field load in the 2¾-inch 12 gauge, while in the 16 gauge, it’s more akin to a magnum. For most non-migratory gamebird hunting, 1-ounce loads should suffice; however, the additional 8-ounce shot could prove handy, when wily birds increase the distance at which they flush.

Moreover, although no loads with extra-light shot charges are contained within the table, know that many require the use of space fillers, such as a nitro card. A few loads employ a combination of an obturator gas seal, nitro card and hard card wad. The best source for low-recoil “light” loads is the most recent edition of BPI’s The Sixteen Gauge Manual.

Evaluation and Reflection

The beauty of a lightweight, true-to-scale 16-gauge shotgun is only recognized through the handling of one. The ability to hastily shoulder and engage fast-fleeing targets is something to behold, as is the reduced fatigue come the end of the hunt. But the delightful heft that makes said shotgun point and swing like a wizard’s wand also makes zippy 11⁄8- and 1¼-ounce shells less enjoyable. In the field, the punchy perceived recoil will likely go mostly unnoticed, but on range, it quickly becomes unpleasant. Therefore, save the 1 1⁄8-ounce or heavier loads for hunting and train with 1-ounce (or lighter) loads at sensible velocities. I’ve yet to encounter a clay target that No. 7½ lead-alloy shot at a docile 1,165 fps won’t break.

The load diversity of the 16 gauge is greatly increased through handloading. BPI’s The Sixteen Gauge Manual is an invaluable resource for assembling high-performance shells and it was extensively used for this article.

Since the shotgun ranges I visit prohibit shot larger than No. 7½, I used that size solely for all loads except those that I’d pattern elsewhere. All shells functioned flawlessly in a Stevens 555E (equipped with improved-modified and modified chokes) and many targets were dusted (some seemingly vanished into a fine cloud of dust). Predictably, those loaded with the Z16 tended to have better effect on fast-steeping, angling and crossing targets at distance, as well as springing teal at longer ranges. Under most conditions, the SG16, Z16, and Claybuster CB0100-16 all performed well across the target presentations and would serve the 16-gauge owner well in the field.

The 16 gauge isn’t particularly finicky with regard to propellants. Those employed in heavy target and field loads in the 12 gauge, such as Alliant Green Dot and Hodgdon Universal, are great choices. Hodgdon Longshot offers incredible flexibility.

Although all loads were utilized on the sporting clays course, select ones were patterned elsewhere at 40 yards using No. 6, 5 and 4 shot. The 555E’s top barrel, which was fitted with an improved-modified choke, was used. While there, I witnessed how careful component selection is essential, particularly as it pertains to payload and shot size. If a larger shot size, such as No. 4, is selected for the 16 gauge, then upping the payload to 1 1⁄8-ounce (versus 1 ounce) is prudent. Make no mistake, a charge of magnum or even better, plated No. 4s can easily create a full pattern at 40 yards, provided that the correct components, shotgun and choke are selected. I was surprised by what said loads achieved. That being said, other than for doves, I still prefer No. 5, No. 5½ or 6 shot for my across-the-board 16-gauge upland shells. Each gun and load perform differently, though, so the only way to know if one meets your expectations is to test it.

“Don’t be afraid of being different. Be afraid of being the same as everyone else.” This anonymous quote is absolutely accurate. Sure, the 16-gauge owner is different but that’s because the shooter understands the benefits and limitations of the lesser-known shotgun – and through careful handloading, its advantages only increase.

Although No. 4s are few in number in the 16 gauge, they pattern densely. This 40-yard patternwas created by a 1 1⁄8-ounce payload propelled by a Z16 wad.

A great all-around upland load in the 16 gauge is 11⁄8-ounces of nickel-plated No. 5s. This 40-yard pattern from an improved-modified choke shows good overall pellet distribution.

.jpg)