.22-250 Remington

A New Twist on Bullets

feature By: John Haviland | December, 20

While the .22-250 has been a popular commercial cartridge for 56 years, it’s time to put a new spin on its bullets to

bring the cartridge abreast of the times. A faster rifling twist than the .22-250’s standard 1:12 or 1:14 rate enables it to shoot the entire range of .22-caliber bullets, including today’s long and heavy target bullets and lead-free and mono-metal bullets.

I’ve been a fan of the .22-250 since I started shooting a Ruger M77 rifle nearly 40 years ago. Back then and for years afterward, the only bullets available to handload had a hollow point or a lead tip in weights that topped out with Speer’s 70-grain bullet with a nose as blunt as a flat tire. I mostly handloaded 50- and 55-grain bullets, and they shot fine through the Ruger’s 1:14 rifling twist and knocked the heck out of prairie dogs, marmots, coyotes and occasionally an antelope.

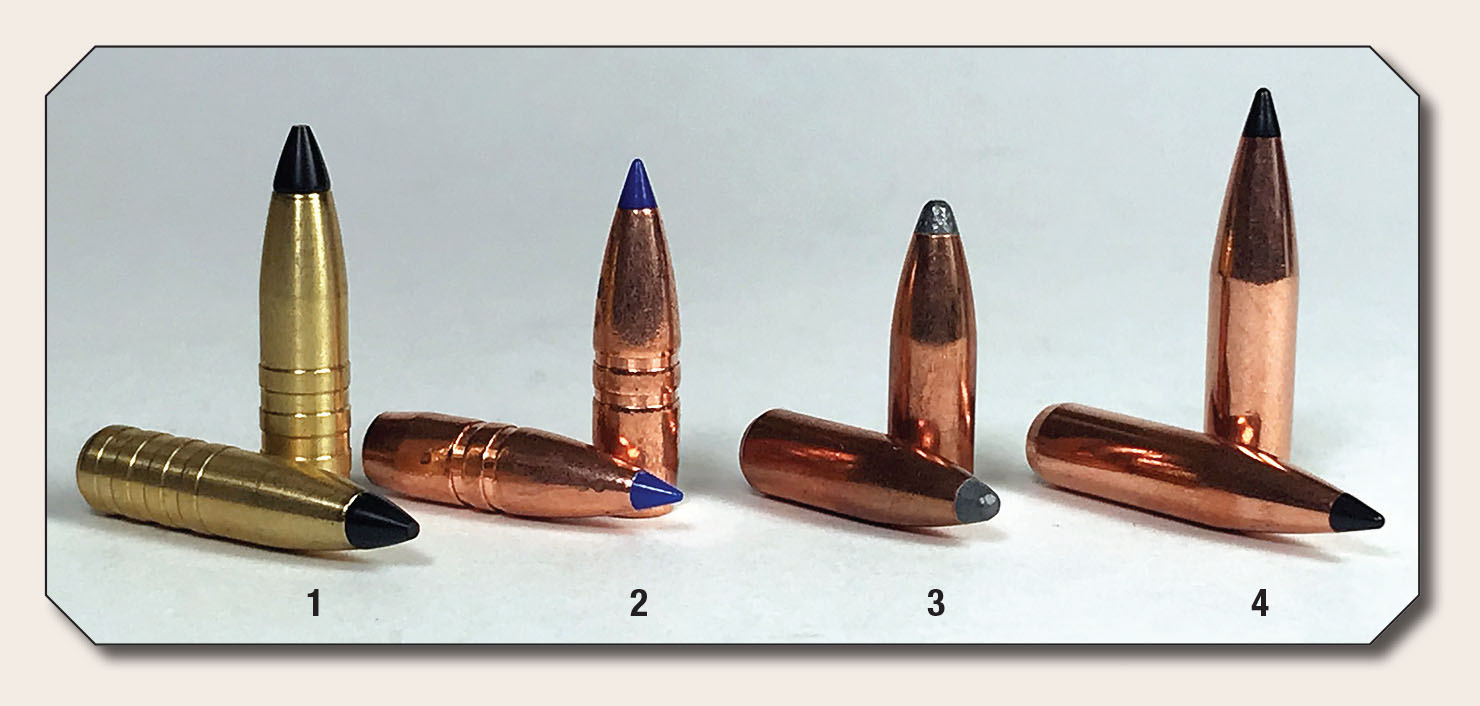

Nosler started me wishing for a .22-250 with a faster twist when it introduced its 60-grain Partition. Its accuracy was adequate when shot from my Ruger M77 and other .22-250s with a 1:14 twist, but it hung on the edge of stability. Sierra opened the floodgate of longer bullets with its slender 69-grain and heavier MatchKing bullets that were seemingly as long as a newly-sharpened No. 2 pencil. Then came Barnes and its X-bullets, then its 55-, 62- and 70-grain Triple Shocks and Tipped Triple Shocks; Hornady with its 60-, 75- and 80-grain A-MAX and now 73- to 88-grain ELD Match bullets; Swift with its 62- and 75-grain Sciroccos and Berger with its 70- to 80-grain Target and VLD bullets.

Most of those bullets were initially intended for 5.56 NATO/.223 Remington rifles with 1:9, 1:8 and 1:7 twist barrels. They too shot great out to 500 yards from several .223 AR and bolt-action rifles with those twists. I figured firing these bullets from a .22-250 would considerably increase their velocity and thus expand shooting fun.

So I started searching for a quick twist .22-250 rifle. I found that Browning, Kimber, Remington and Winchester put a 1:14 twist in the barrels of their .22-250 rifles. Cooper and most Savage rifles have a 1:12 twist, although Savage’s heavy LRPV rifle and the Ruger American have a 1:9 twist. Nosler also puts a 1:9 twist on its rifles.

I finally told custom gunsmith Charlie Sisk what I wanted. Sisk is no fan of a fast twist for the .22-250. He believes a slower twist, like 1:12, provides better accuracy with the most commonly shot .22-caliber bullets that weigh up to 60 grains. But I insisted, and he relented. He started to work on the rifle with a Lilja barrel with a 1:8 twist and a 22-inch long sporter-weight contour threaded into a Sisk action based on a Stiller’s Precision Firearms Predator action. He screwed the barreled action into a High Tech Specialties classic synthetic stock. I mounted a Nikon Titanium 5.5-16.5x 44mm scope in Talley steel fixed rings on the rifle and the whole outfit with a sling weighed 8.5 pounds.

Bullet Selection

There is a lot of talk about faster than normal rifling twists over-stabilizing some bullets and ruining accuracy. Such factors exist but will not appear within the distance a .22-250 can fire a bullet. Examples include Berger 40-grain Flat Base Varmint and Hornady 40-grain V-MAX bullets that require a twist rate to stabilize them nearly two times slower than the 1:8 twist in my Sisk rifle. At 100 yards, the Berger bullets grouped as tight as .60 inch, and Hornady bullets .29 and 1.28 inches at 300 yards. If over-stabilization was going to rear its ugly head, it would have by the time the bullets reached 300 yards.

The only bullets to avoid are those with an ultrathin jacket. The rapid rotation from a quick twist and the .22-250’s relatively high velocity tears bullets, such as the Sierra Blitz and Hornady SX, to bits when they leave the confines of the bore. When such a bullet rips apart, it looks like a puff of pepper in front of the muzzle. The solution to that is to shoot bullets with a thicker jacket. The Sisk rifle shot Hornady 40-grain V-MAX bullets at nearly 4,300 feet per second (fps) with great accuracy.

A short-action has plenty of length to contain a .22-250 cartridge with a

A barrel bore with a fast twist requires a correspondingly extended throat to accept cartridges much longer than the .22-250’s established maximum of 2.350 inches. For instance, Nosler 69- grain Custom Competition bullets

contact the start of the rifling in the Sisk rifle with a cartridge length of 2.555 inches. Seating the bullets slightly deeper, to a cartridge length of 2.520 inches, resulted in a perfect fit with the base of the bullet even with the bottom of the case neck and cartridges that fit in the rifle’s magazine with plenty of room to spare.

Powders

Powders with a burn rate of IMR-8208 XBR on the fast side to CFE 223 on the slow end shot 50-grain and lighter bullets the fastest from the Sisk .22-250. Varget performed well with several lighter bullets. For instance, 36.0 grains of Varget paired with Sierra 53-grain MatchKing bullets produced an extreme velocity spread of 29 fps over 30 shots, and six five-shot groups measured an average of .76 inch at 100 yards.

Top velocities with heavier bullets required relatively slower burning powders like Reloder 17, SUPERFORMANCE and IMR-4831. A case filled with 38.0 grains of Reloder 17 fired Nosler 69-grain Custom Competition bullets at 3,375 fps, and 41.5 grains of SUPERFORMANCE fired the Nosler bullets at 3,464 fps. AR-Comp grouped five of the Nosler bullets in slightly over an inch at 100 yards with an extreme velocity spread of 23 fps.

Velocity was somewhat slower than expected shooting Sierra 77-grain MatchKing and Berger 80.5-grain BT Fullbore bullets. Still, accuracy was great with the MatchKing bullets paired with IMR-4831, with five bullets grouping in .62 inch at 100 yards, and another five in 2.42 inches at 300 yards.

All the bullet choices present a fortunate problem when shooting a quick-twist .22-250. To start, you can shoot a lightweight bullet, like a Hornady 40-grain V-MAX, at upwards of 4,300 fps to thin hordes of ground squirrels infesting farm fields. Such extended shooting, though, is hard on rifling. A Berger 40-grain Varmint bullet fired 1,000 fps slower pushed by a light amount of IMR-3031 or W-748 extends barrel life and shooting fun.

Whether .22-caliber bullets are suitable for hunting big game the size of deer and antelope is always debatable. My family has had good luck shooting Nosler 60-grain Partition bullets from various .22-250s to take deer and antelope over the years. Ranges were not all that far, perhaps 250 yards or so at the outside. The .22-250’s flat trajectory makes it possible to shoot much farther, but that would steal from the excitement of the stalk.

I loaded a batch of Cutting Edge 55-grain Flat Base Raptor bullets with Varget powder the first hunting season with the Sisk .22-250 rifle. My son fired a Raptor bullet at a whitetail buck walking toward him at about 40 yards. The bullet was traveling about 3,600 fps when it hit the buck in the base of the neck and the deer dropped dead right there. The only sign of a bullet hole was a slight leak of blood. Skinning the deer exposed a small piece of brass stuck on the outside of the shoulder. The front petals of the Raptor bullet are designed to break off on impact and leave the shank of the bullet to continue to penetrate, and that’s what it did for about 10 inches.

.jpg)

The next fall, I loaded Barnes 55-grain Tipped Triple Shock bullets with 37.0 grains of Varget for a muzzle velocity of 3,687 fps from the Sisk rifle’s 22-inch barrel. With the bullets hitting 2 inches above aim at 100 yards, they dropped 1.5 inches at 300 yards and 10 inches at 400 yards.

My son again took the rifle hunting, this time for antelope. Thomas crawled to the crest of a ridge and spotted a buck below. His rangefinder displayed a distance of 305 yards. Thomas aimed tight behind the buck’s shoulder and fired when the buck turned broadside. The little bullet carried only 900 foot-pounds of energy at that distance, yet the buck jumped ahead a few steps and fell over. The bullet had punched out the far side ribs and left a hole the size of a quarter.

Most hunters carrying a .22-250 pursue coyotes and red fox. Most of the time these predators run up close to the call and present a short shot. Other times, though, suspicion causes them to stop and stare at a distance. The movement of using a rangefinder or dialing up elevation on a scope will spook them. So I mainly shoot 55-grain bullets, like the Nosler Tipped Varmageddon or Sierra BlitzKing, with a muzzle velocity of 3,700 fps. With those bullets hitting 2 inches above aim at 100 yards, I can aim right on the money out to 325 yards.

One winter I sat on a snowdrift with my back against a fence post. After a few minutes of blowing my best rendition of a cottontail rabbit in distress, two coyotes ran out of the sagebrush toward me. Something looked suspect, though, and they stopped far down the fence line. I estimated the range somewhat over 300 yards and fired. One coyote dropped and the second nearly turned itself inside out to run back into the sagebrush.

I entered the ballistic coefficient and velocities of several bullets into a ballistics program to determine what, if any, advantage heavier bullets provide over 55-grain bullets. Turns out, high velocity contributes a lot to creating a flat trajectory. Sierra 55-grain BlitzKing bullets with a muzzle velocity of 3,700 fps drop about 3 inches less at 500 yards than Nosler 69-grain Custom Competition bullets starting out at 3,400 fps, and 8 inches less than Sierra 77-grain MatchKings that start their journey at 3,050 fps. The heavier bullets do drift a couple inches less in a 15-mph crosswind and carry about 15 percent more bullet energy at 500 yards than the 55-grain BlitzKing. That makes the heavier bullets a good bet shooting coyotes across the incessant wind of a wide prairie basin.

Over the decades, the .22-250 Remington has shown it is truly an everlasting cartridge, and it’s even more versatile with quick-twist rifling that provides a wide choice of bullet designs and weights. Mine has become a constant companion throughout the year. During the spring and summer I shoot 40-grain bullets at a mild velocity to shoot ground squirrels and the occasional marmot. The rifle is still in hand and loaded with a big-game bullet, like a Barnes Tipped Triple Shock, come fall when the leaves shiver gold on the quaking aspen. To sweep out the cobwebs of winter, the rifle takes hikes across the snowy foothills in hopes of fooling a coyote.

.jpg)