In The Black

All is Not Equal in the World of Black Powder

feature By: Terry Wieland | December, 20

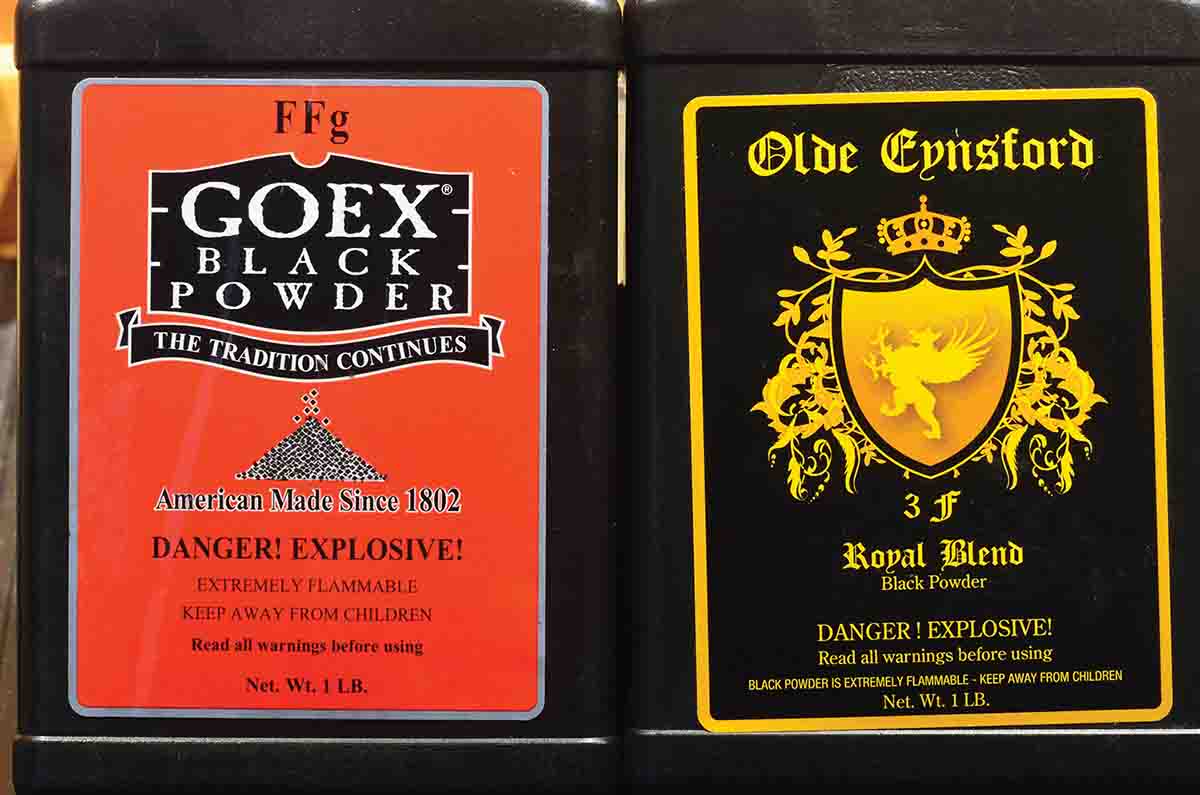

A few years ago, I found myself in a gathering that included a GOEX executive. GOEX is the American black-powder company, now owned by Hodgdon, successor to a long line of explosives manufacturers stretching back to DuPont, Hazard’s and Laflin & Rand. In the course of our conversation, this gentleman became insistent – and later forcefully insistent – that his company’s products were not only the best available today, they were as good as any black powder ever produced. The basis for his position, apparently, was the results of various laboratory tests. Any idea that Curtis’s & Harvey’s No. 6 was better, he simply dismissed as myth and folklore.

Evaluating them is tricky. It’s not at all like comparing different types of smokeless powders, for a number of reasons. First, smokeless powders are chemical compounds. Without getting much further into it than that, we can say that what differentiates smokeless powders are their relative burning rates, which are dependent on such factors as grain size, shape and coating, as well as their chemical makeup.

Black powder, on the other hand, is a mechanical mixture of charcoal, sulfur and saltpeter. It’s an explosive (for lack of a better term) that releases all of its energy in one big bang. (It is not quite that way, technically, but it doesn’t matter.) Unlike smokeless powders, however, much of this energy is turned into smoke and solid compounds left behind to foul the bore. In theory, at least, the only thing that determines black powder burning rates is grain size, with Fg being the largest and FFFFg the smallest, with some almost dust used only for priming pans and such.

To an experienced black-powder shooter, this explanation may be simplistic to the point of absurdity, but for newcomers to the game, overly technical explanations may be incomprehensible. The purpose here is to give some practical guidance. In my own case, my experience with smokeless powders goes back 55 years, but I’ve been using black powder in various guns and rifles for only a decade or so. What I’ve found is that black powder is fascinating in its own right, but you have to check preconceptions at the door and approach it as a whole new field of endeavor.

Black powder’s three components – sulfur, saltpeter and charcoal – do not vary too much, although there are differences in the charcoal, and to a lesser extent in the saltpeter. If there is a difference between, for example, Curtis’s & Harvey’s No. 6 and today’s Olde Eynsford, it almost has to be in the charcoal, and the only real difference there can be in the wood used to produce it. The one explanation I’ve heard most often is that the better powders of old were made with charcoal produced from alderwood or, sometimes, willow. My acquaintance from GOEX, quoted earlier, dismissed that as fairy tales and quoted, again, lab test results. I offer that for what it’s worth.

Being possessed of a chronograph, several percussion revolvers and an inquiring mind, I decided to see how some of the currently available powders compared.

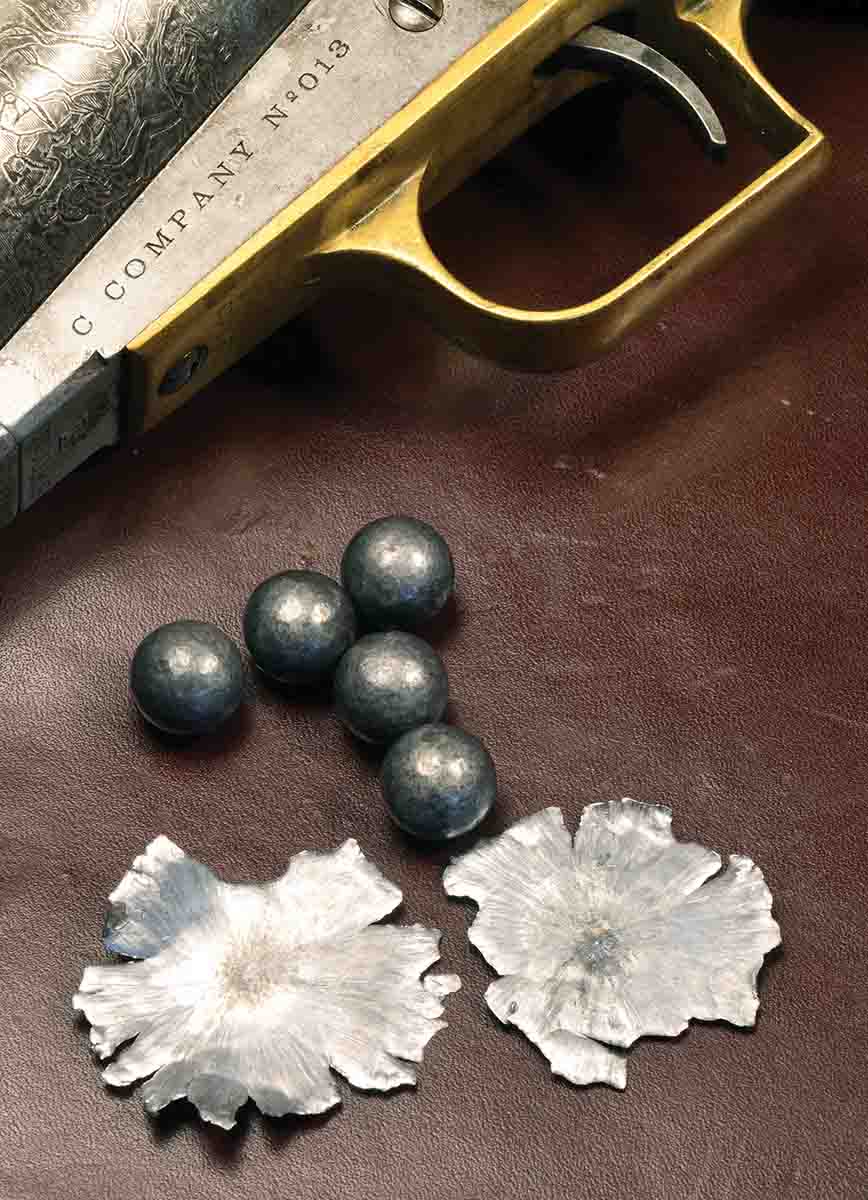

The Walker is one of the most famous guns in American history. It was the cornerstone on which the Colt empire was built, changed the history of Texas and shaped the way cavalry was used from 1850 onward. There were only 1,100 made, of which only about 200 are known to still exist. One described as “most desirable” to collectors sold at Rock Island two years ago for about $1.8 million. Obviously, an owner of one is not about to take an original Walker out and use it for a test gun.

A better reason for not using an original is the design of the cylinder and the quality of the steel. The steel was the best available at the time – Samuel Colt would not use any other – but it still left something to be desired. Of the 1,100 Walkers manufactured, 239 were known to have been destroyed early on by cylinders bursting. Various explanations have been offered. One, the cylinder was very long (27⁄16 inches), which allowed too much powder to be stuffed into it. Two, each gun was issued with a bullet mould that cast both a roundball and a cylindrical bullet. The latter were too difficult to load, so some of the soldiers loaded them upside down. This supposedly resulted in excessive pressures and destroyed cylinders.

The quality of the steel is not a problem with either the 1,500 Walkers that Colt produced as commemoratives in 1981, nor with reproductions like the Cimarron Arms.

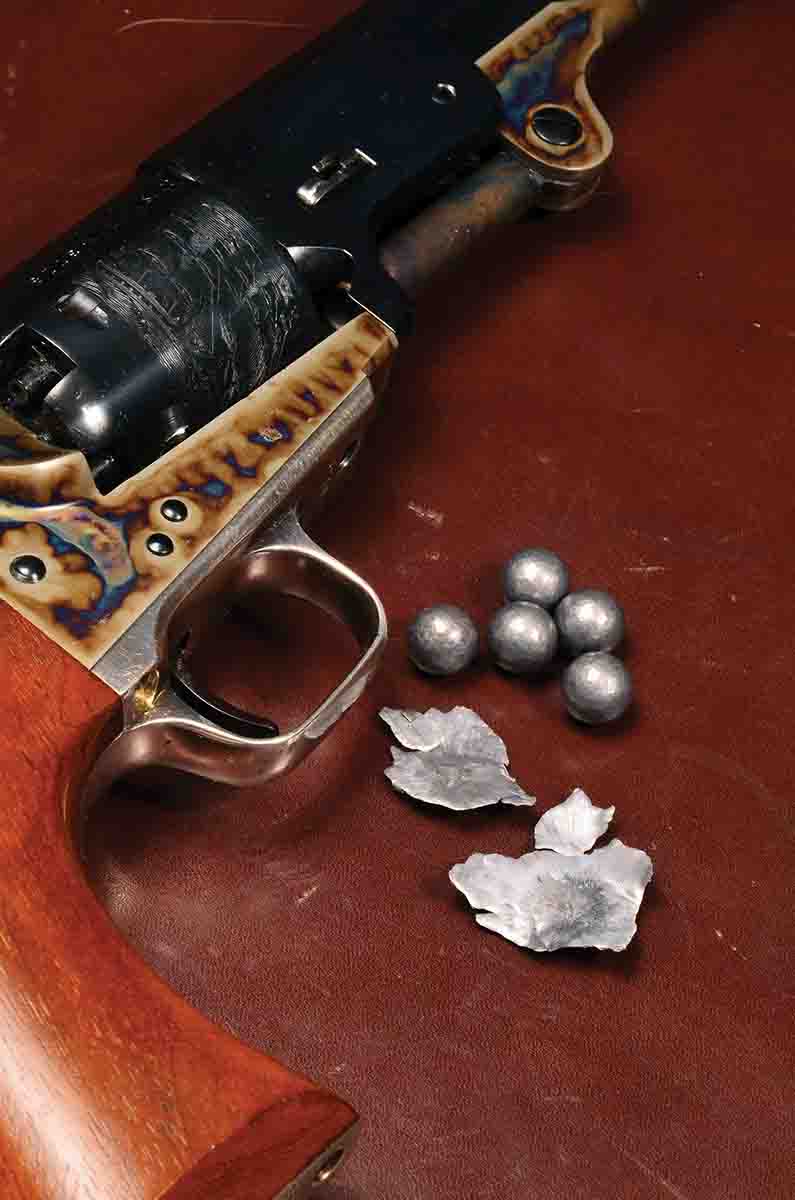

It was found early on that a pure lead roundball was the most effective projectile, as well as easiest to load, and no one can argue with their accuracy. For this test, I used .44- and .36-caliber Hornady balls. (Nomenclature aside, the .44 is actually a .454, and the .36 is a .375.)

The Colt Navy, made in 1971, came with an interesting set of instructions. It essentially said to stuff it with any black powder of any grade, using any projectile, and rest assured nothing bad would happen; the projectile would leave the muzzle on schedule, in a cloud of smoke. I didn’t push it, being a fainthearted type when dealing with explosives. Suffice to say, the Hornady balls in front of prudent loads of black powder produced some very gratifying results.

The powders I was able to acquire early this year were somewhat restricted by the global lockdown, which hampered both supply and delivery, but combined with what I had on hand, it added up to a good cross section.

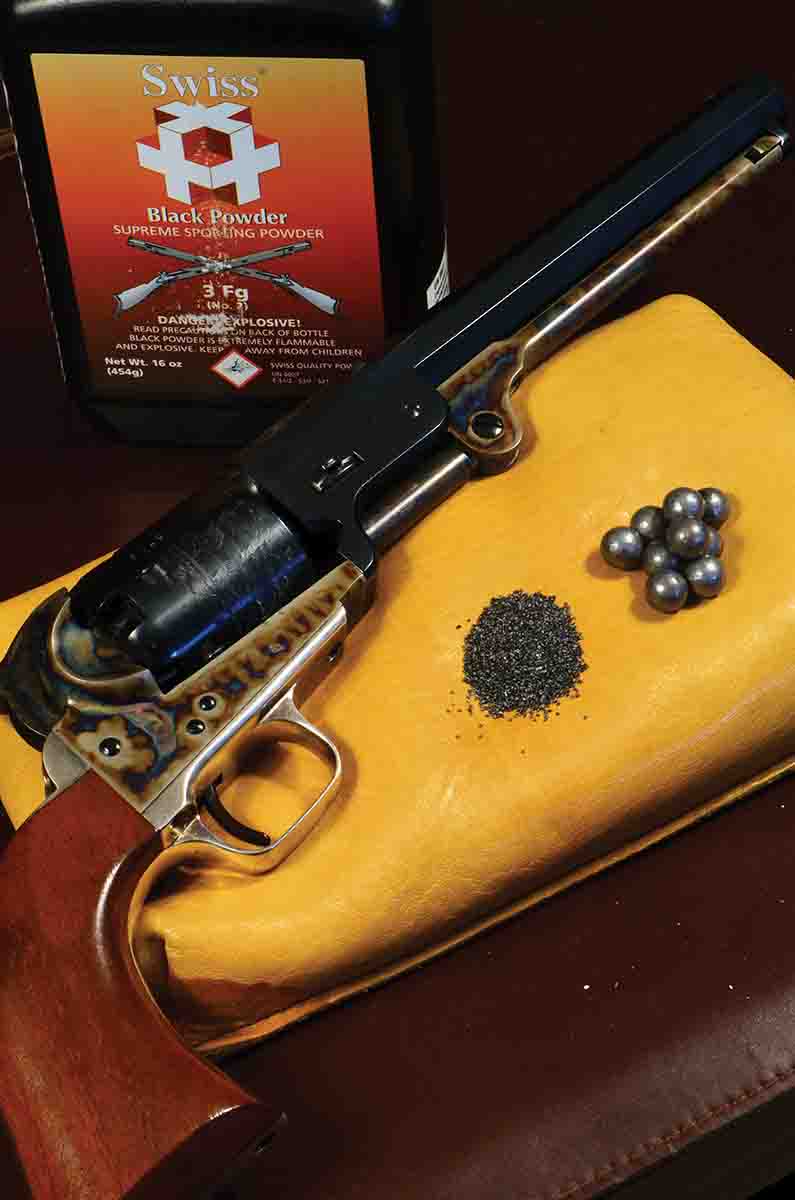

James Kirkland at Schuetzen Powders contributed both his Schuetzen brand and the famous Swiss, which has been described as the standard of excellence.

As a general comment, it’s fair to say that the original Walker, while universally admired, had some flaws, which Colt corrected in subsequent models, and that the 1851 Navy was a vast improvement in several ways. The table for the Navy is self-explanatory. Using 17 grains of powder in each load, I fired six shots over the chronograph to get velocity and extreme spread. Everything worked well, with no real surprises except the difference in velocities.

All the GOEX products were very consistent. Because I had some on hand from before they disappeared from the GOEX line, I tried loads with GOEX Express and GOEX Black Rifle. These have apparently been superseded by Olde Eynsford. All four GOEX products delivered velocity in the 750/780-fps range, and extreme velocity spreads ranged from 39 to 66 fps. Ignition was reliable.

The big surprises were the Schuetzen and Swiss powders. Schuetzen delivered the lowest velocity while Swiss was by far the highest. At 17 grains, there was still room in the chamber to increase the load, so these should not be taken as maximum velocities in any case.

The Walker was somewhat more complicated. Load recommendations range from a low of 30 grains to a high of 60. I settled on 49 as a comfortable medium. At least, it was comfortable until I shot it with Olde Eynsford FFg and Swiss 1½ F. Those both delivered velocities over 1,000 fps, but every shot resulted in the loading ram snapping down. This was recognized as a problem with Walkers and corrected in the Dragoon and all subsequent Colt revolvers by having a catch to hold the loading ram in position. Having the ram snap down in the midst of a gunfight could jam the cylinder, with dire consequences. This was one more reason to keep Walker loads on the modest side, but as you can see, even a modest load with a 140-grain ball would be something to contend with.

Incidentally, the cylinder can accommodate more than 49 grains of powder if higher velocity is desired. For subsequent shooting, I used GOEX FFg, and it performed with admirable consistency, the loading ram stayed in place, and it was comfortable to shoot. At more than four pounds, however, shooting a Walker is pretty tiring.

It’s important to remember that manufacturers of black powder may be seeking something more than velocity. For example, for target use, high velocity is rarely the goal, whereas cleaner (or moister) burning for cleaning the bore between shots very much is.

With both guns, I used Wonder Wads between the powder and the ball to guard against chain firing – an ever-present hazard with percussion revolvers.

Another area in which modern components don’t compare with those of old is percussion caps. They come in two sizes: too big and too small. Standard Remington No. 11 primers fit the Walker all right, as well as its successor Third Model Dragoon, but are decidedly loose on the smaller Navy. Having a percussion cap drop off the nipple, down into the innards of the mechanism, can tie up a gun pretty well, too.

I developed a method of squeezing the caps slightly before putting them on, which kept them in place. Unfortunately, the various capping tools cannot accommodate a slightly flattened cap. You can squeeze the cap with your fingers, but applying enough pressure to get the cap to flatten at all usually caused it to flatten too much. Now I pick up a cap with needle-nose pliers, set it on a .125-inch Allen key and squeeze it down. Once you get the hang of it, 100 caps can be ready in a few minutes, then keep them separate for use on smaller nipples.

.jpg)