.357 Remington Maximum

Loading a T/C Contender for Deer

feature By: John Barsness | December, 20

Remington and Ruger eventually coordinated to bring out a commercial version, with Remington making the ammunition and Ruger introducing a larger version of its Blackhawk revolver. However, the Maximum’s average pressure was set at 40,000 PSI, an increase of 5,000 PSI over the .357 Magnum. Combined with the increased powder charge, the Maximum resulted in quick gas-cutting of the Blackhawk’s frame, and only about 7,700 left the factory.

The gas-cutting problem did not apply to the single-shot Thompson/Center, and eventually the .357 Maximum became reasonably popular in the Contender, especially among hunters, which is how I got involved with one. Eileen and I live near a wildlife management area (WMA) administered by the Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife & Parks, along both sides of the Missouri River where it flows into a reservoir. The WMA provides public hunting for a variety of game from mourning doves to moose, but Eileen particularly loves to hunt white-tailed deer, and public riverbottom whitetail hunting is relatively scarce in Montana, because the land along most rivers is often private farm and ranchland.

However, since farms, ranches and an increasing number of subdivisions surround the public WMA, centerfire rifles are not allowed. Instead, hunting is limited to archery, muzzleloaders, shotguns, and “traditional handguns, not capable of being shoulder-mounted,” with a barrel less than 10.5 inches long chambered in a straight-walled cartridge not originally developed for rifles.

Since we moved here in 1990, she has primarily hunted the WMA with shotgun slugs, taking not only whitetails but a cow moose. Around 2007, however, she started getting recoil headaches – and slug guns tend to kick pretty hard. Eventually, we narrowed the problem down to more than about 15 foot-pounds of recoil, so she switched from a 12-gauge pump to a 20-gauge single shot, using Winchester saboted ammunition loaded with 260-grain, .45-caliber Partition Gold bullets at a listed 1,850 fps (a load I had previously used on a good-sized whitetail buck in Iowa, using a T/C Contender Carbine with a rifled slug barrel).

She shoots handguns pretty well, partly because she uses them quite a bit to hunt small varmints, especially the Richardson’s ground squirrels (locally called “gophers”) that can devastate hay and grain fields. A typical gopher weighs less than a pound, a pretty small target for an open-sighted .22 rimfire revolver or semiauto.

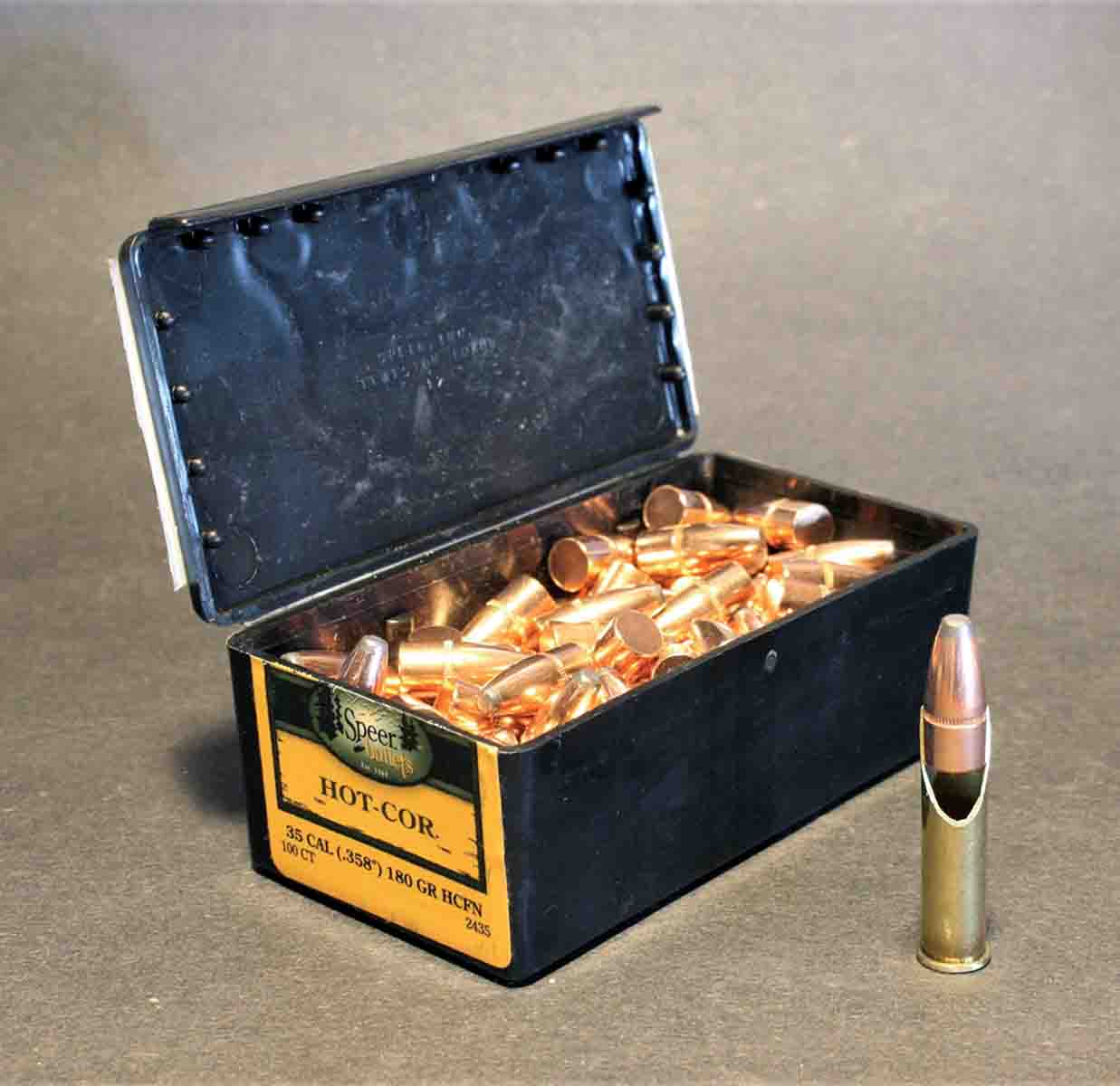

However, she preferred a scoped handgun on the WMA because the deer, like hard-hunted whitetails everywhere, tend to move most in the dim light of dawn and dusk. After talking it over, I suggested a Thompson/Center Contender in .357 Maximum, partly because I had always been somewhat intrigued by the cartridge. She wondered how a .35 caliber would work on deer, and I reminded her of the several whitetails she had dropped very quickly with Speer 180-grain Hot-Cor bullets designed for the .35 Remington, started at a velocity similar to the Winchester 20-gauge sabot loads.

She did not use the 180s in a .35 Remington, but in an old German over/under combination gun she fell in love with at the Wisdom, Montana, gun show. It had a 16-gauge shotgun barrel underneath a rifle barrel. The seller claimed the rifle barrel was for the 9.3x72R, a long, straight, rimmed black-powder round that appeared in the 1880s, then made the transition to smokeless.

The gun’s marks showed it had been proofed for smokeless powder, and I assured her I could load some ammunition. She bought it – and got lucky because the rifle barrel was actually for the 9x72R, a similar cartridge supposedly using a 9mm-diameter bullet, about .354 inch. However, when I slugged the barrel, the bore and grooves turned out to be essentially .35 caliber. After measuring the case capacity and making some calculations, I handloaded the 180-grain Hot-Cors with IMR-4895, settling on 40 grains for around 1,800 fps.

It really thumped whitetails, including a couple out around 150 yards, whether she put the bullet through their shoulders or ribs. Plus, all had exited, leaving good-sized exit holes – and copious, but short blood trails. As a result, she already had plenty of confidence in at least one moderate-velocity, medium-weight .35-caliber bullet.

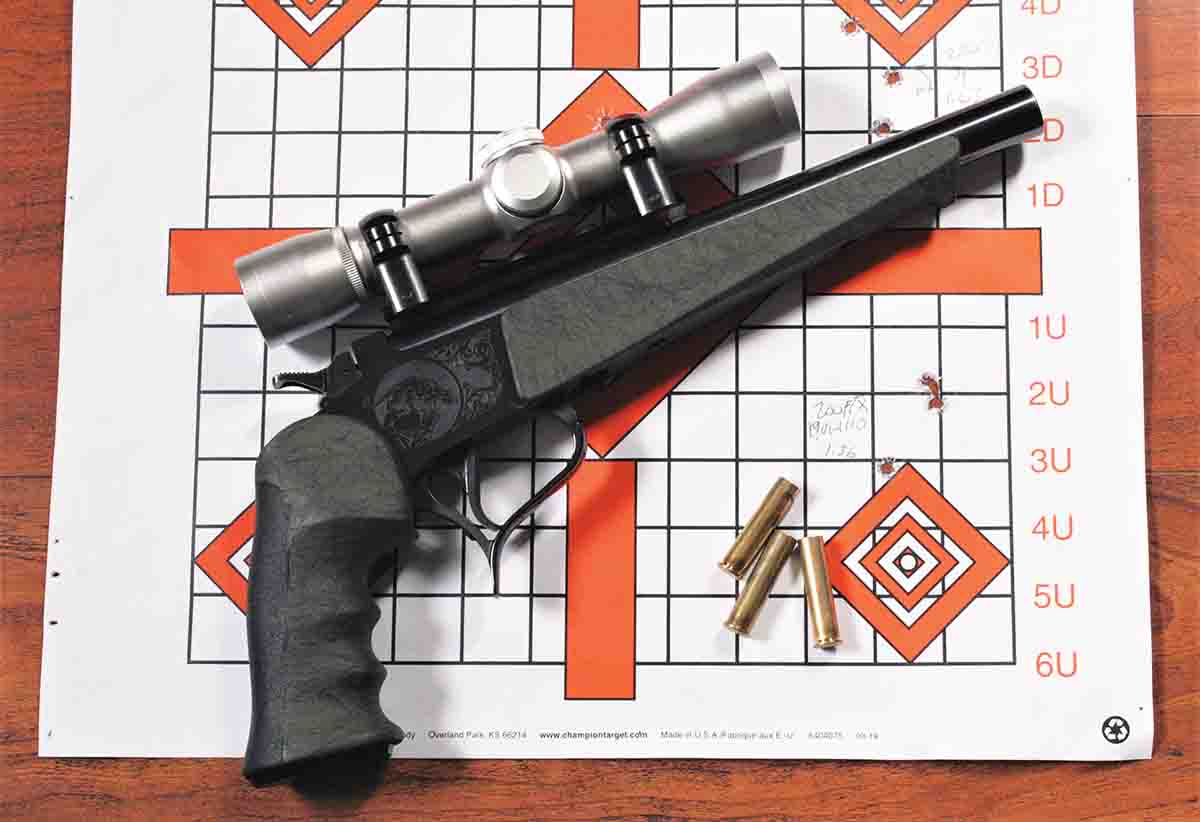

I posted an ad on the internet site 24hourcampfire.com, and within a few days I bought a synthetic-stocked Contender with a 10-inch Bullberry custom barrel, and a silver-finish 2x Weaver handgun scope. Our local friend, Bob Jeffrey, saw the ad, and while he had already sold his .357 Maximum Contender, he still had a bag of new Remington cases and most of a box of Hornady 180-grain XTP bullets. (One of the missing XTPs had worked well on a doe on the WMA, leaving a good-sized exit hole on a 40-yard rib shot.)

When the Contender arrived, I decided to try some of the heavy- bullet .357 Magnum factory ammunition on hand, partly to see if the scope was sighted-in. A Remington load with 165-grain Core-Lokts got around 1,400 fps, with three-shot groups averaging about 2.5 inches, right at point-of-aim at 50 yards. Winchester 180-grain Partition Gold ammunition chronographed about 1,350, and groups averaged under 2 inches, with one measuring 1.25 inch. Neither load would do a whitetail any good – but unfortunately neither is still available, and of course any self-respecting handloader would expect to do better.

I decided to gather all available .357 Maximum data, then try loads listed as producing the highest velocity, or flagged for accuracy. This turned out to be interesting, because not all reloading data sources include the Maximum, and a few had even dropped it from more recent manuals. (Another interesting discovery occurred while searching local stores for .35-caliber bullets – a total absence of .357 Maximum factory ammunition.)

By far the most common powder listed in the available data turned out to be Hodgdon H-110, which is also Winchester 296 poured into a different canister. Some listed other spherical powders, or very fine-grained extruded powders.

All the data used small rifle primers, most often Remington 7½s, partly because of the high pressure of the Maximum, which can be too much for the thinner cups of small pistol primers, and partly because small rifle primers are “hotter,” so work better with larger powder charges. (Some sources also suggested a “heavy” crimp for a more consistent powder burn.) I decided on the CCI 450, probably the hottest American small rifle primer, partly due to having very good luck with 450s and spherical powders in several rifle cartridges, including the .22 Hornet.

The handloads were put together with carbide RCBS .38 Special/.357 Magnum dies, which have not only loaded those two rounds for decades but also the 9x72R, which might be considered a “.357 Ultra-Maximum” (though the rim is a little wider, taking a .30-30 shell holder). The only problem occurred when I discovered none of the several seating plugs in the box were shaped correctly for the three rifle bullets.

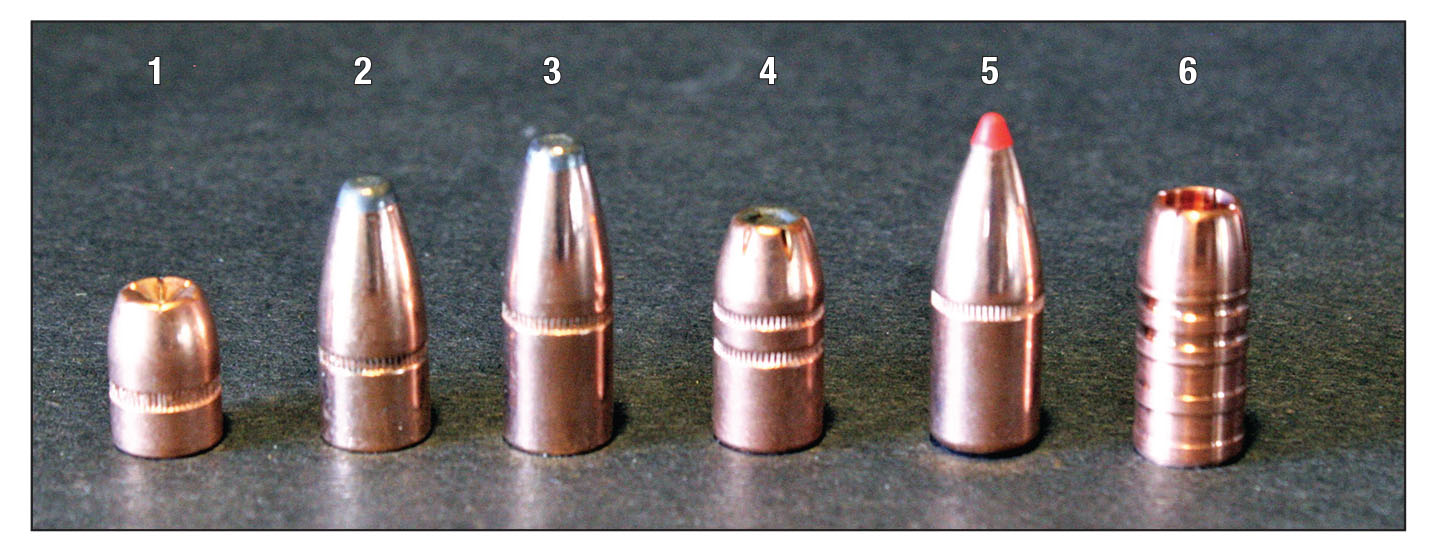

The 180- and 220-grain Speers are essentially flat-nosed spitzers. (In fact, the Speer website lists the 180 as a “Spitzer Soft Point,” but the 220 as a “Soft Point Flat Nose,” even though they have exactly the same profile, or at least they did on August 14, 2020, when I checked the site.) The core is pretty soft, the reason the 180s expand well down to at least 1,400 fps, and a typical flatnose seating plug often started to “mushroom” the flat tip. The 200-grain Hornady FTX is a real spitzer, with a soft plastic tip for safe use in tube-magazine rifles, which also tended to flatten when seated.

I am sure spitzer seating plugs are available from several handgun die makers for .357 Maximum handloaders, but with a surfeit of seating plugs, I decided to make one by drilling out a round-nosed plug with increasingly smaller drill bits. I then polished the “stepped” hole with a piece of medium-grit emery cloth spun with a Phillips- head screwdriver bit mounted in my old DeWalt drill.

Another difficulty occurred with larger powder charges due to over-compression with some bullets – and not necessarily heavier bullets. The 140-grain Cutting Edge Raptor handgun bullet is a copper monolithic, around 50 percent longer for its weight than a typical lead-core 140-grain hollowpoint. To fit the Contender chamber, the Raptor also had to be crimped on its forward groove, with about 0.5 inch of the shank inside the case. The 180-grain Speer flat-nosed spitzer, however, ended up with about 0.3 inch of the shank inside the case, and the 200-grain Hornady’s shank was only slightly longer, due to not being designed to fit inside a revolver cylinder.

With longer-shanked handgun bullets, the compressed powder often pushed the bullet forward a little, even after heavy crimping. None of the H-110 charges required much (if any) compression, one reason it shows up so often in .357 Maximum data.

The powder charges I settled on are generally a grain or two less than listed as maximum in manuals for the same bullet weight, yet get approximately the same velocity. This may be due to tighter internal dimensions in the custom Bullberry barrel or using CCI 450 primers, though at least one manual used 450s.

Of course, bullets also vary in hardness and friction, which can be due to the material, shank length, or both. The pure copper of the Cutting Edge Raptor is “grabbier” than the typical jackets of lead-core bullets made of a mild brass called gilding metal made by alloying copper with 5/10 percent zinc.

The 140 Raptor, in fact, resulted in the greatest disparity between published muzzle velocities and my chronograph results. Hodgdon lists 26 grains of H-110 for the 140-grain Speer jacketed hollowpoint for 2,001 fps out of a 10-inch barrel. However, even the company’s starting load of 24 grains proved too hot with the Raptor, resulting in sticky cases and chronographing 2,150 fps! Reducing the charge to 22 grains approximated Hodgdon’s velocity, and the cases quit sticking.

The Raptor did not group as well as most other bullets, even though my Smith & Wesson Model 66 .357 Magnum likes it fine. That said, the Raptor .357 Maximum load still shoots well enough for big game and can be used in California, or other places requiring “non-toxic” bullets.

Overall, the Bullberry barrel preferred heavier bullets, even though the rifling twist is 1:16, while factory Contender barrels in .357 Magnum are 1:14. In general, point-of-impact at 50 yards shifted relatively little, especially considering the wide disparity in bullet weights. Several of the loads could be used interchangeably without tweaking the scope adjustments, including the cast-bullet load, which not only works great for inexpensive practice but would not shoot up much meat on edible small game, such as one of the cottontail rabbits inhabiting the WMA. (You will not find that in any manual. Instead, I picked it up on the internet, and loaded some test rounds after cross-checking it with .357 Magnum data. One three-shot group at 20 yards – a typical range for woods bunnies – ran around an inch.)

By the time this article is published, Eileen will have practiced considerably with the Contender, perhaps partly by hunting bunnies with the cast bullet load. The cottontail population seems to be peaking this year, and we both prefer their pale meat to pheasant.

I do not know which of the deer loads she might choose, but suspect it might just feature the 180-grain Speer. We shall see…

.jpg)