Cartridge Board

.300 Weatherby Magnum

column By: Gil Sengel | December, 20

Of equal importance is that Weatherby was a sterling example of the free enterprise capitalism ingrained in American culture. He built a business, shouldering all responsibility for success or failure, with no approval or assistance from any government agency.

Weatherby also experienced a bit of good luck in that in 1937, Winchester had announced its new Model 70 would be chambered in .300 H&H. When World War II ended, it was soon possible to get a hot, new .300 WM for just the cost of a standard grade Winchester M70, plus a few dollars for rechambering.

This was not the first attempt at greatly increasing the velocity of heavy, .30-caliber hunting bullets. Cartridge designer Charles Newton created the .30 Adolph Express (later called the .30 Newton) in 1912 on a case having a base diameter almost equal to the .375 H&H belt diameter. Also, sometime prior to 1940, a Los Angeles gunsmith named Ralph Miller created a wildcat he called the .300 PMVF (Powell-Miller-Venturified-Freebore). Built on a full-length .300 H&R case, it had a concave (“venturified”) shoulder and a chamber cut with .750 inch of freebore to lower pressure. It has been said this is the origin of the Weatherby cartridges because they too were said to use a lot of freebore early on, which negatively affected accuracy.

I don’t know about accuracy, but early original Weatherby rifles I have chamber cast do show varying amounts of freebore. None have been .750 inch. We hear nothing about this today, probably because our more strongly constructed bullets seem less affected by bullet jump.

O’Connor had his own .300 H&H rechambered by Weatherby, but included no freebore. Using 77 grains of the same powder in this rifle caused primers to fall out, so he dropped down to 75 grains. O’Connor had no way to measure velocity, but a steel plate at 200 yards that was only dented by a factory .300 H&H round “offers about as much resistance to the 180-grain Weatherby Magnum bullet as a piece of cardboard.” No comment!

By 1955, Weatherby was publishing figures showing a 110-grain bullet achieving 3,997 fps muzzle velocity, a 150 grain at 3,660 fps, a 180 grain at 3,400 fps and 220 grain showing 3,000 fps. All ammunition had been loaded in Weatherby’s shop from fireformed Winchester .300 H&H brass. Now, Norma in Sweden was producing cases, and in a year or so, would take over all ammunition production. This was a godsend for Weatherby.

High velocity is Weatherby’s trademark, which in the .300’s case meant bullets traveling about as fast at 350 yards as .30-06 bullets at 100 yards. Results were fine at long range, but bullets of the time often could not stand the impact velocity at 100/200 yards. Reports came in of animals wounded due to bullet breakup and lack of penetration.

The company wrestled with this problem for years, first offering factory ammunition loaded with Nosler Partitions in 1965. Other custom bullets were added as they proved themselves. Today there are nine. Five are 180 grains at about 3,240 fps muzzle velocity. Two are 165 grains at 3,350 fps and 3,390 fps. One is 150 grains at 3,540 fps and one 200-grain bullet is listed at 3,000 fps. This is more than any other Weatherby round and shows why the .300 WM is, and has always been, the company’s most popular cartridge. Bullet failure is a thing of the past. Using today’s custom bullets, the .300 Weatherby is adequate for any North American big game, including the white bears of the frozen north and the brown bears of the semi-frozen north. Virtually all African game can be included as well.

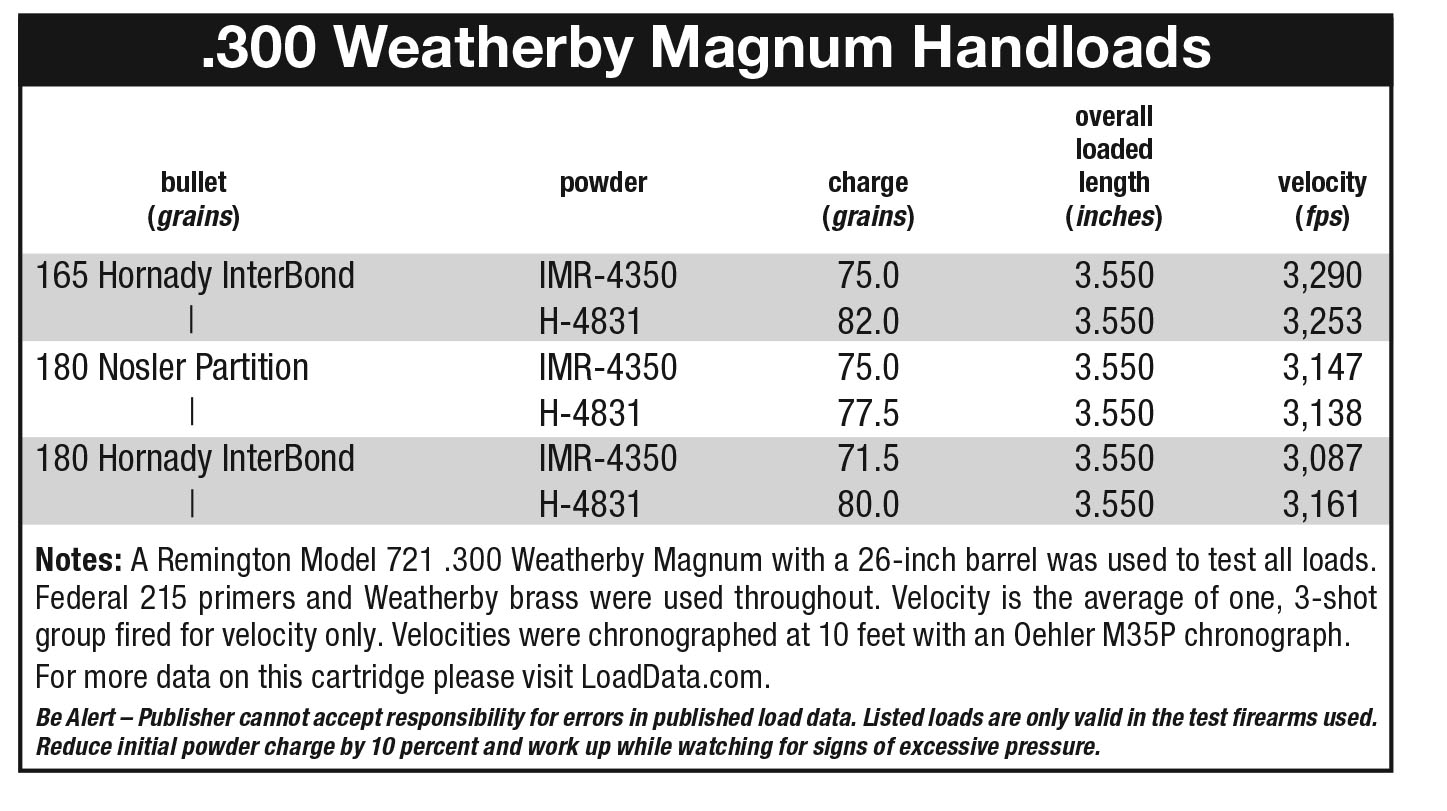

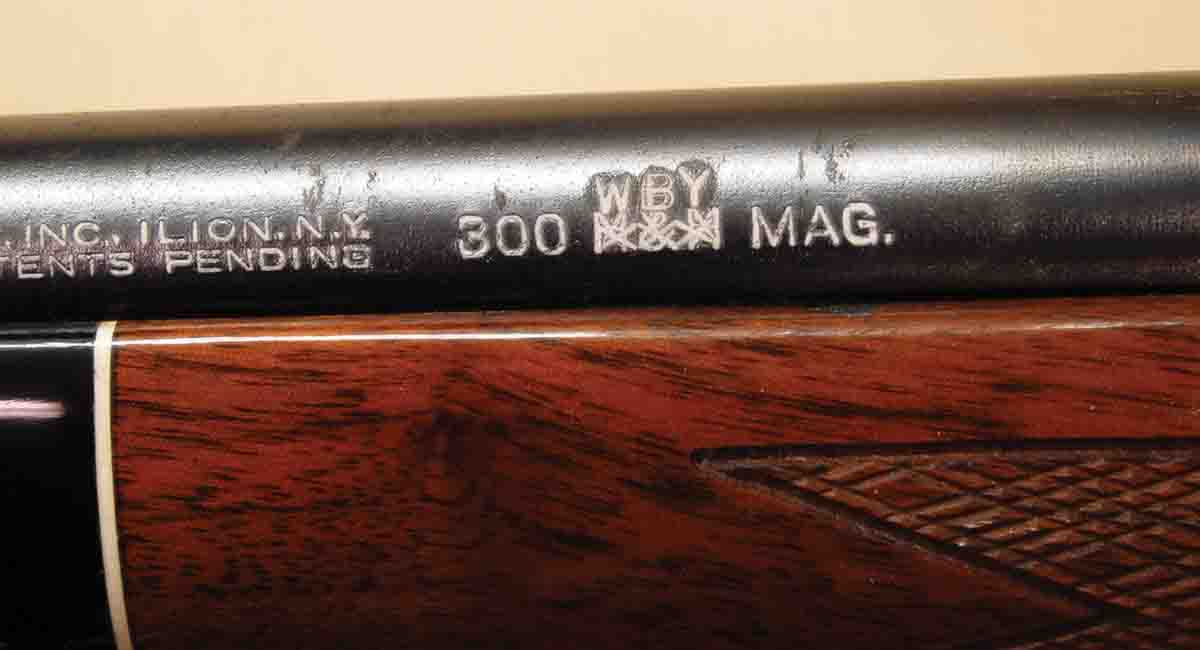

The .300 Weatherby shot here is an interesting early rifle. Originally a Remington M721 in .300 H&H Magnum it was rechambered by well-known gunsmith and barrelmaker W.T. “Bill” Atkinson in Prescott, Arizona, perhaps in the 1970s. Freebore is .290 inch. It was then fit into a Remington 700 BDL stock, creating what was sometimes called a “New York Weatherby” since Remington was in Ilion, NY.

Using current Weatherby factory ammunition containing 180- grain Hornady InterBond bullets, it is easy to see why the .300 WM is so popular with hunters who need the power and long-range performance. Sighted at 250 yards, trajectory is equal to my .22-250 with 55-grain bullets. One shot, however, makes it obvious the

rifle is no .22-250! Recoil is quick and about 30 percent greater than a .30-06 with the same bullet weight, but it’s easily controlled once one knows what to expect. It’s also noisy. Sighted at 300 yards as Weatherby does in its data, the bullet is only down 8.7 inches at 400 yards. That’s a very long way to shoot big game; wind, weather and light become more important than simple bullet drop at such a distance. The .300 WM also delivers more energy at 400 yards than the .243 Winchester or 6.5 Creedmoor do at the muzzle!

One doesn’t hear much about the .300 WM today. Perhaps because it’s not a new round and there is nothing to complain about. Yet, at last count there were 27 total factory loads available from Weatherby, Nosler, Hornady, Remington and Federal. That says a lot about the .300 Weatherby Magnum, which one gun writer (probably in a weak moment) recently called “the king of big-game cartridges.”