.25-20 Single Shot

An old star can still sparkle.

feature By: Terry Wieland | February, 19

By the 1880s, long-range target shooters had come to the conclusion that smaller calibers were better than larger ones. What they lacked in down-range ballistic performance they more than made up for in reduced recoil. As a result, the popular .40s of the 1870s gave way to the .38-55, which in turn was replaced by the .32-40, with more forward-looking shooters turning to the earliest .28s, and Pope (among others) looking at the .25.

F.J. Rabbeth, one of the foremost Schützen competitors of his day and a member of the famous Walnut Hill club near Boston, is generally credited with creating the original .25-20. As told by Ned Roberts and Ken Waters in The Breech-Loading Single-Shot Rifle (Wolfe Publishing, 1988), Rabbeth had worked for Remington Arms and, around 1886, the company built a special rifle for him in .25 caliber using a cartridge created by necking down the .32 Wesson.

In 1889 Rabbeth published an article about his experiments with the .25 in Shooting and Fishing. First offered in the Maynard rifle, the .25-20 was put on the market with ammunition from Union Metallic Cartridge. Later, because it was too long to work through its new Model 1892 lever rifle, Winchester shortened it, gave it a sharper shoulder and created the .25-20 WCF; thereafter, the original, longer cartridge was known as the .25-20 Single Shot.

Other .25 calibers followed, including the .25-21, .25-25 and .25-35, but the one that became the target- shooting stalwart was the .25-20 SS. One of the most famous companies to adopt it was Stevens Arms, which chambered it in thousands of its Model 44 single shots, for both target shooting and small game. It was offered by ammunition companies well into the twentieth century, and one of the most successful of .22 wildcats, the R-2 Lovell, was based on its case. So popular was the R-2 Lovell, and so great its demand, in the 1930s Griffin & Howe prevailed upon one ammunition company to produce a large run of .25-20 SS brass just for producing R-2 Lovell

Today the .25-20 Single Shot is almost forgotten – until someone stumbles on a lovely old single-shot rifle chambered for it and starts searching for a way to put it back into action. Since it was a standard chambering for a long time in rifles by Stevens, Winchester and just about everyone else, there is no shortage of those old rifles around.

Although originally a black-powder cartridge, the .25-20 adapted well to smokeless powder. It did not, however, fit well with jacketed bullets, mainly because the steel in older barrels would not take the wear. If you want to keep gilt-edged accuracy in a .25-20 SS, it is best to stick to cast bullets. They are generally more fun to shoot anyway and are considerably cheaper. As well, there are all kinds of older bullet moulds around, designed specifically for the .25-20 SS. If you cast your own, you are in your element.

The first and biggest problem is brass. Rule out any original brass you might find. Aside from being a collector’s item, its uncertain history might include black powder and corrosive primers, which will make it unreliable at best. In recent years, B.E.L.L. produced a run (around 1988) and its successor, Jamison Industries, also produced some; Bertram Brass of Australia still makes it, and it’s usually available from several sources. It retails for more than $3 per round, including shipping, but if a handloader is careful it should last a long time.

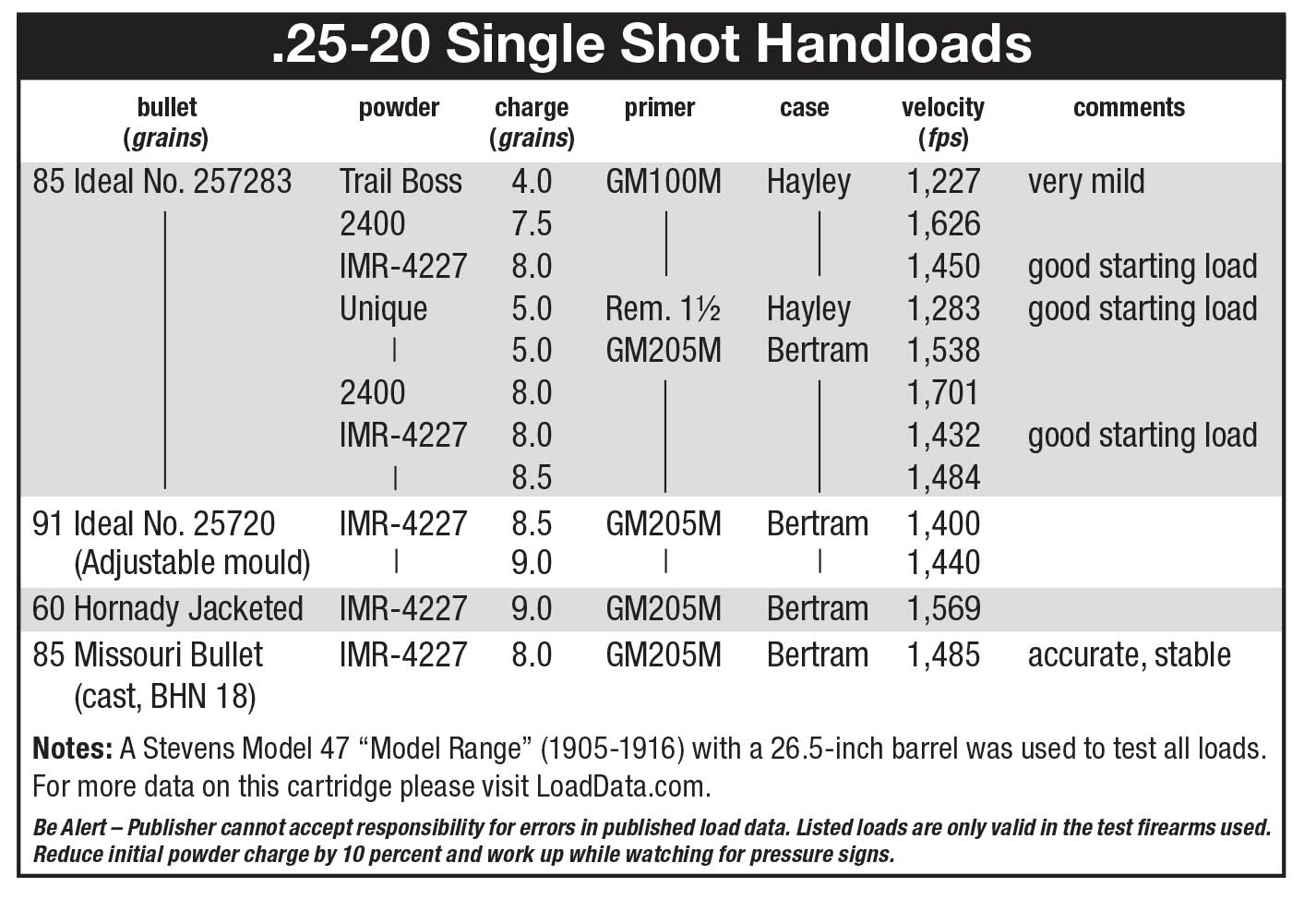

To see how drastic the difference is, I compared two cases. The new, primed Bertram case weighed 69.4 grains while a sim-ilar Hayley case weighed 85.3 grains; the Bertram, filled to the mouth, held 18.5 grains of 2400 powder while Hayley brass held only 16.4 grains. Working with new Hayley brass, I had about a 10 percent failure rate (case splitting) until I backed off starting charges significantly. A load that is mild and works well in Bertram brass might be too hot in the reduced-capacity Hayley brass, so loads should be worked up independently for each.

Another consideration is that while Hayley brass might fit your chamber, standard-dimension dies might be too tight. I sent some fired cases to Redding, which tailored a sizing die to my dimensions. This not only promotes accuracy, it reduces work-hardening and extends case life.

Primers can be either small rifle or small pistol. Bob Hayley recommends small pistol primers in his brass as a way of helping to keep pressures down, and I used

One should plan to devote some time to case preparation, especially with Hayley brass. It needs to be carefully conditioned, with flash holes checked for obstructions, the neck carefully opened up and then slightly belled. Because of his production process, Hayley brass has thicker neck walls that can actually swage a soft lead bullet down to a smaller diameter if not sized to .257 first. The necks can, of course, be reamed to thin the brass.

Redding supplies two dies in its standard set. These are fine if you are starting with Bertram brass, but not with Hayley’s. For that you need a die to open the neck up to .257, and Lyman makes one for that purpose. There are several other approaches that can be used, such as the K&M neck-sizing iron. None of these are terribly expensive – not when saving time, effort and the cost of hard-to-find brass is considered.

Your first load in a new Hayley case should be considered part of the case-conditioning operation – a very gentle load that will expand the brass to fit the chamber and allow you to see how everything fits together. After that you can neck-size only.

There is not much in the way of modern load data for the .25-20 SS, and what can be found in old manuals may be limited to powders that are no longer available. However, data for the .25-20 WCF can be used; in fact, older manuals (like Ideal Handbook No. 34, from 1940) often combine the two.

As with any cartridge originally intended for black powder, it is best to stick to mild loads using middle-of-the-road powders. The two 4227s (IMR and Hodgdon) are probably the best powders for the .25-20 SS, and since they are identical, data for either can be used. Trail Boss works, but velocities are low; Unique also works but can be a little violent.

The key considerations for accuracy and reliable operation are bullet weight and velocity, and the need to get enough velocity for the slow rifling twist to stabilize long bullets. The original flatnose bullet for the .25-20 SS was about 87 grains, depending on the alloy. Anything heavier than 90 grains is unlikely to work well. My ideal velocity range is 1,450 fps to 1,650 fps; anything faster adds nothing except recoil and wear and tear.

There are so many variables involved in loading the .25-20 SS that it’s difficult to cover them all. However, there are a couple of things to keep in mind. First, attempting to boost velocities beyond what is needed for bullet stabilization is pointless. Doing so can, and usually does, result in sticky extraction and occasional brass splitting. Second, excessive velocity combined with pure lead bullets and the shallow rifling often found in target rifles can result in the bullet stripping in the rifling, leading to heavy lead fouling and tumbling bullets. A certain amount of experimentation is required to see what hardness of bullet your rifle prefers. I found that some pure lead bullets (Ideal No. 25720) were stripping and tumbling, but the Missouri Bullet Company’s Brinell-18 hardness bullets, available from Graf & Sons, work beautifully.

Bertram and Hayley brass not only demand different case conditioning to begin with, they require a different process in reloading.

Conditioning Bertram brass: The neck is oversized for .257-diameter bullets, so run them into a full-length resizing die first, then into an internal neck die to open up necks to correct diameter and slightly bell the mouth. Ream the flash hole and chamfer the mouth inside and out. They are then ready to prime and load. After shooting, they can be full-length resized. I prime Bertram brass with small-rifle primers.

Conditioning Hayley brass: The neck is far too tight, to the point of swaging down soft cast bullets if force is used in seating. As well, when new, the mouth is slightly crimped from the swaging process. Tap gently with a K&M neck-sizing iron to open them up just enough to allow the inside neck die to enter. This then sizes the neck completely as well as slightly belling the mouth. Ream the flash hole and chamfer the mouth inside and out. You may want to ream the inside of the neck to thin the brass. When reloading Hayley brass, I neck-size only, and prime with small pistol primers.

Since the majority of .25-20 Single Shot rifles are intended for targets and cartridges are loaded one at a time, crimping is not only unnecessary, it’s actually detrimental. Here we run into a problem because most seating dies either impart a crimp or leave the mouth untouched. Since the mouth must be belled slightly to accept the bullet without damage, you need a way of ironing out the mouth so that the neck is straight and chambers easily. Redding made up a special die for me that seats the bullet and also un-bells the case mouth, leaving it perfectly straight.

As I write this, my three main sources for arcane brass (Graf & Sons, Huntington Die Specialties and Buffalo Arms) are all out of stock on Bertram .25-20 SS brass, although Buffalo Arms still lists its custom-loaded ammunition in this caliber. This gives an idea of how many shooters are still happily shooting the .25-20 Single Shot. That is also a measure of how much fun these rifles are to shoot.