Shooting The .300 Ham'r

Handloads for a Feral Hog Zapper

feature By: John Barsness | February, 19

Twenty-first-century America seems to be crowded with “trending” lists, and for many hunters feral pigs rank right up there. Despite being highly edible, over the past couple of decades pigs have become the biggest varmint in the country. Once considered a problem in the South, their numbers are increasing in northern states, where some biologists thought winters would kill them off: Colorado, Michigan, New Hampshire, Oregon, Vermont and Washington. This should not have been totally surprising, as Europe’s truly wild “boars” (Sus scrofa, the ancestor of domestic pigs) live as far north as southern Finland, Norway and Sweden.

Wilson Combat recently introduced another tool for feral pig hunting, AR-15s chambered for its new .300 HAM’R cartridge, essentially an elongated version of the .300 Blackout. Before delving deeper, it should be noted that Bill Wilson is a pig-huntin’ fool, so he had plenty of experience to help design the new cartridge. (In this instance, “fool” is a compliment, not an insult.)

I know this from hunting pigs with Bill on his Circle WC Ranch back in 2010, near the tiny town of Cuthand in northeast Texas. He was already well into his search for the perfect AR-15 pig cartridge and at the time was concentrating on the 6.8 SPC. I shot several pigs during three days and one night, when we ventured forth with Bill’s night-vision binoculars and one of his suppressor-equipped 6.8 SPCs with a night-vision scope. He had determined Barnes TSX bullets designed for the 6.8 were most effective on pigs, especially big boars, and 110-grain TSXs worked very well on the sizeable black-and-white boar I shot that

At the time I had been hunting feral pigs since 1989 in California, Missouri and other parts of Texas. That night near Cuthand we eventually stalked within 100 yards of a boar, the closest of a loosely scattered herd rooting in a cattle pasture. While the suppressor muffled the report, the rest of the pigs immediately ran for the nearest brush due to hearing the rifle’s action cycling.

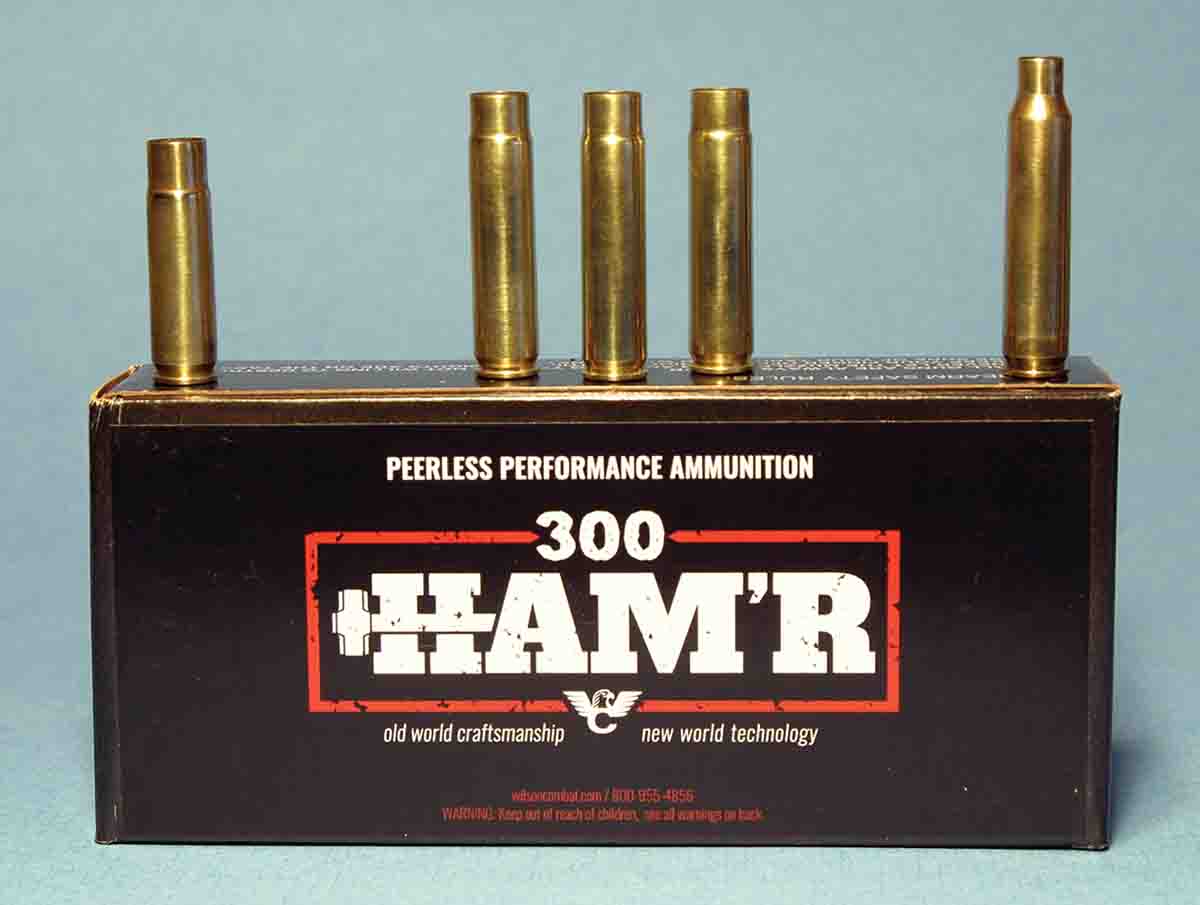

Bill also tried the .300 Blackout extensively, finding it no more effective on pigs than the 6.8 SPC, and not nearly as flat-shooting, even with lighter bullets. Despite the effectiveness of the 6.8 SPC, however, he eventually believed larger-caliber, heavier bullets would work better on big boars, and eventually ended up “stretching” the .300 Blackout case about .23 inch. A piezoelectric pressure laboratory did a bunch of testing with various powders, eventually settling on 58,000 psi as maximum, about halfway between the .223 Remington and 5.56 NATO. The new cartridge was then field-tested on more than 200 pigs, and it worked better on larger boars than the 6.8 SPC.

The .300 HAM’R also has a magazine capacity advantage over the 6.8 thanks to its somewhat thinner case body. Contrary to what a few shooters assume, the 6.8 SPC is not the 5.56 NATO/.223 Remington necked up. Instead it uses a case .044-inch larger in diameter, reducing AR-15 magazine capacity about 17 percent.

Unlike some other light rifles, however, the balance was equally impressive. Even with an 18-inch fluted barrel, the balance point fell right between my hands. Aiming offhand at 100 yards turned out to be easy, a quality perhaps even more helpful than light weight in a rifle designed for rapid shooting at moving animals.

In my eagerness to shoot the Lightweight Hunter, I took it to the range with four of the Wilson factory loads before reading the extensive background information Bill had e-mailed. Three-shot groups averaged .96 inch at 100 yards, and it occurred to me that the rifle was the twenty-first-century equivalent of a Model 94 Winchester .30-30 carbine, both in ballistics and weight/handling. I let Bill know how well the rifle performed, mentioning this insight.

In a far more polite way, he replied, “Duh,” suggesting I read the background information. It turned out he had actually considered naming the new round the “.30-30 AR,” but as a good friend pointed out, “Only us old guys know and care much about the old thutty-thutty!” (Apparently I qualify as one of those old guys.) Wilson had previously introduced his .458 HAM’R cartridge for AR-10s – a cartridge somewhat more powerful than the .458 SOCOM – and had trademarked the name. His son Ryan suggested reusing HAM’R, a perfect double entendre for a pig-hunting round.

During the .300’s development it became apparent very few powders would be appropriate for the case. This is not unusual in “mild” rifle cartridges, as pointed out in my article on .22 Hornet-based rounds in Handloader No. 314 (June 2018). These days we have plenty of powders for zippy rifle rounds, but relatively few for more moderate cartridges.

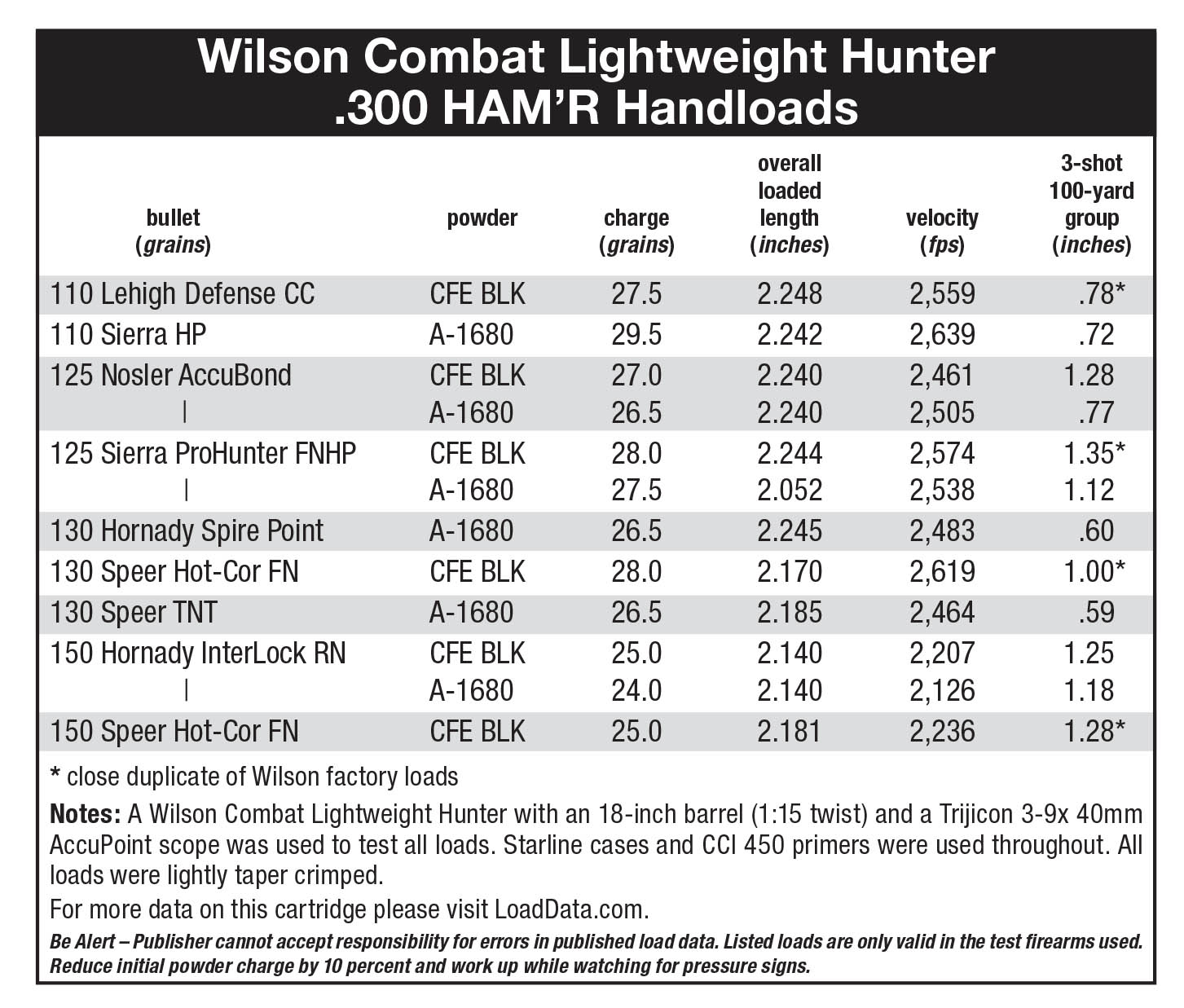

The two powders that really worked well turned out to be Hodgdon CFE BLK (designed for the .300 Blackout) and Accurate 1680, with CFE BLK slightly edging out A-1680 in most loads. “CFE,” of course, stands for “copper fouling eraser.” All the Wilson ammunition was loaded with CFE BLK, and after the range session I took a look inside the barrel with a Hawkeye bore-scope. Only a faint hint of copper showed along the edges of the lands, certainly not enough to affect accuracy.

At first I was somewhat doubtful the Nosler 125-grain AccuBond would leave enough room for the powder charge because it’s a relatively long plastic-tipped boat-tail, but it worked fine. This is a great bullet in the .308 Winchester, with full-power loads duplicating 130-grain .270 Winchester muzzle velocities, trajectory and wind-drift out to 400 yards, yet it also works well with somewhat re-duced loads for recoil-sensitive hunters.

While muzzle velocity in the .300 HAM’R was about 200 fps slower than the reduced loads I’ve used in the .308, the 125-grain AccuBond has a relatively high ballistic coefficient for a light .30-caliber bullet, so it retains downrange velocity very well. According to Nosler, AccuBonds expand at velocities down to 1,800 fps, and a little calculating with a ballistic program indicated the .300 HAM’R load should expand easily at 200 yards, and probably 250.

Sighted-in 1.5 inches high at 100 yards, the bullet lands 1.5 inches below point of aim at 200, and 6 inches down at 250. For interested readers, kinetic energy at 250 yards is right around 1,000 foot-pounds, which is generally considered plenty for game like pigs and deer. So while the .300 HAM’R is not a long-range hunting round, it works beyond “woods ranges.”

Bill also sent along some new Lehigh Defense 110-grain Controlled Chaos monolithic hollowpoints designed specifically for the .300 HAM’R. I reported in Handloader No. 314 (June 2018) on the excellent results achieved with Lehigh’s 18-grain Controlled Chaos bullet in a .17 Hornet, and this bullet proved to be equally impressive, grouping into less than an inch at just about 2,500 fps.

I set the stack of paper 25 yards from the muzzle, where impact velocity would be high. Not surprisingly, the monolithic Lehigh 110-grain bullet penetrated deepest (9 inches) while retaining 89 percent of its weight. However, the other two bullets also performed very well, as I expected after field experience with both. The Nosler 125-grain AccuBond penetrated 8 inches and retained 78 percent of its weight. While the Hornady retained only 42 percent of its weight, it was the heaviest bullet so it still penetrated 7 inches. (Hornady InterLocks I’ve recovered from big game have retained an average of about half their weight, give or take 10 percent.)

None of this was totally surprising, since one of the virtues of the .30-30’s moderate muzzle velocities has always been consistent bullet performance on big game. Bill has also had great field results with the Speer 130- and 150-grain Hot-Cors.

Of course, one advantage of the .300 HAM’R over, say, the .458 HAM’R, is lighter recoil. The calculator in Sierra’s Infinity program computed the recoil energy of the tested loads from 7.2 to 8.1 foot-pounds in the Lightweight Hunter; about half that of a typical 150-grain .308 Winchester factory load in an 8-pound rifle. This not only makes practice very pleasant, but it allows much faster repeat shots if somebody runs into a bunch of pigs. Of course, a muzzle brake or suppressor would reduce recoil slightly more, though the relatively small powder charges in the .300 HAM’R will not result in as much reduction compared to larger-capacity rounds.

The five .300 HAM’R models offered by Wilson come with barrels from 16 to 20 inches long, and all but one has a threaded muzzle. They vary from 6 pounds to 6 pounds, 7 ounces in weight without a scope and mounts, though one model, the Ranch Rifle Package, comes with a 3-9x 40mm Trijicon.

Another factor in any rifle’s shootability, of course, is the trigger. In this instance the trigger is a Wilson Combat Tactical Trigger Unit (TTU) listed at 4 pounds. Like many AR triggers, it has a two-stage pull, but the take-up is very light and short, and the trigger on the test rifle broke extremely crisply at an average of 3 pounds, 11 ounces as measured with a Timney trigger scale. I would have guessed the pull at somewhat less before measuring, which is typical of very crisp triggers.

The dies provided were Lee Precision, which worked fine, produced ammunition with minimal bullet run-out and also included a length/sizing gauge for insuring resized cases would chamber easily. Redding also makes dies, and along with the Wilson ammunition, the Hunting Shack in Montana also makes HSM .300 HAM’R loads with Sierra 135- and 150-grain bullets. Black Hills Ammunition in South Dakota plans to offer ammunition in early 2019. Seekins Precision will also be making AR-15s and barrels in .300 HAM’R.

Bill Wilson said he spent more time on this single project than any other in his long career, and it looks like the .300 HAM’R will be a hit – except among feral pigs.