Learn To Reload (Handloading Basics)

A Look at the Necessary Tools

feature By: John Haviland | February, 19

The press was mounted on one end of a work bench in the basement. The other tools and powder were stored in one drawer and primers in another.

As teenagers, we stumbled a few times when reloading, mostly with measurements, but nothing serious. As we gathered experience, we added additional tools. After all these years, handloading has remained a great pastime, made shooting and hunting more enjoyable and saved me untold dollars. Well, maybe I never saved any money compared to if I had remained an occasional shooter.

Robin Sharpless, vice president at Redding Reloading Equipment, said the demographic of people starting to reload has changed in recent years. “Used to be, people took up reloading to save money,” he said, “and they were satisfied if their reloads were accurate enough for casual shooting at the local gravel pit.” Redding’s surveys now show people interested in reloading are in their 40s and 50s and want to buy quality tools that will last a lifetime. “I call them ‘handloaders’ because they also want to save money and at the same time make better ammunition than factory-produced ammunition,” he said. These handloaders start with basic tools and later add specialty tools that refine their handloads and save time at the loading bench.

Lyman, Lee Precision, Hornady, RCBS and Redding sell reloading kits with almost all the equipment required to reload. They range in price from $200 for the Lee Breach Lock Challenger Kit to over $800 for the Redding Versa Pak Pro reloading kit.

Presses

Lyman’s Tom Griffin and Sharpless both recommend a single-stage press that can be used to load one cartridge at a time for new handloaders. Progressive presses that perform most, or all, loading steps with one pull of the press handle require exact attention to each station’s setup and constant monitoring of the reloading process. “Do you want to make one mistake at a time, or six or eight?” Sharpless asked.

Most single-stage presses are classified by their frame shape. C-frame presses, like the Lyman Brass-Smith Ideal Press, have an open front for an unobstructed view and hand access for inserting and removing cases from the shellholder that sits atop the ram, and placing bullets in a case mouth and guiding them into the die as the ram raises them into the seating die. “O” presses with a rectangular-shaped frame, like the Hornady Lock-N-Load Classic, are constructed with a front pillar that connects the base and top of the press, making the press rigid to withstand the force required to size rifle cases while keeping the shellholder and reloading dies aligned. The front column on most of these presses is offset to the right to provide a larger opening for the insertion and removal of cases. Positioning the front of the shellholder to the left, so cases can be inserted and removed from the side, provides even more finger room. The handle on the RCBS Rock Chucker Supreme press (and some others) mounts on the left or right for ambidextrous use.

The RCBS Summit single- stage press operates in the reverse of a regular press. A die threads into a base that rides up and down on a 2-inch diameter ram. Pulling downward on the press handle lowers the die onto a case. The whole idea of a die locked into a thick base on a central column is to ensure everything is in alignment. With no frame support brace required, the front of the press is completely open. The Summit press does not contain a primer seating tool.

Most single-stage presses, though, incorporate a primer arm. Placing a primer in the arm’s cup and pushing the arm into a slot in the ram aligns the primer with the case’s primer pocket and seats the primer on the down stroke of the press. Optional primer feeders like the Lyman Auto-Primer Feed include a frame that attaches to a press to hold tubes that dispense large or small primers one at a time.

Though Redding does not make a hand tool for seating primers, Sharpless said he much prefers using a hand tool to a press-mounted priming arm. “I like the feel a hand tool gives to let you know primers are seating to just the right depth,” he said.

Most shotshell presses look like a progressive press for centerfire cartridge with dies at different stations to complete each step of the reloading process. Some are progressive, and each pull of the handle rotates cases to the next station and performs a reloading step. Others are single-stage presses that require manually moving a shotshell case from one station to the next.

Dies

Sharpless and Griffin suggest buying a two-die set that includes a seating die and full-length sizing die to reload bottleneck rifle cartridges. A full-length sizing die is versatile. For full-length sizing cases, the die is

As the press ram’s mechanical linkage cams over, it removes any space between the die and the shellholder. The setting completely sizes the case neck to hold a bullet tightly, and it also sizes the case body so it fits in any appropriate chamber. A full-length die can also be set a partial-turn away from contacting the shellholder to set case headspace to match a specific chamber. Another slight upward turn of the die sizes part of the neck without setting the shoulder back. A cartridge loaded with such a case provides a close fit in the chamber it was originally fired in. Cases must be lightly lubricated before sizing. Griffin suggests using specific case lubricants that are applied to a lube pad on which cases are rolled.

A regular seating die aligns a case and bullet with the die’s bullet-seating stem to seat bullets straight within the case. The die can be positioned to only seat the bullet, or it can be threaded inward a slight amount to also crimp the case mouth to the bullet’s cannelure.

For five times the cost of a regular two-die set, specialty seating dies can be bought, like the RCBS Gold Medal Match or Redding Competition dies. Hornady and

Reloading manuals list the overall cartridge length of specific bullets seated in different cartridges. When I first started handloading, I seated bullets in .30-06 cases so cartridge length was the same as a factory cartridge. The first cartridges I loaded with roundnose bullets fit in my rifle’s magazine with room to spare, and cartridges chambered freely. But when I opened the bolt to remove a loaded round, the bolt handle required extra pull. All that came out was the case, and powder spewed all over. The bullet remained stuck in the rifling because the bullet had not been seated deeply enough.

A dial caliper solved that problem. The caliper precisely provided an exact cartridge length in .001- inch increments. Eventually I used the caliper for measuring all cartridge dimensions like case lengths and bullet diameters. Electronic calipers with a digital display are especially easy to read – until the batteries die.

A three-die set is required for straight-wall cases like the .45-70. An expander die is a necessary third die, and its expander ball widens the inside of the case to the proper diameter to accept the bullet, and it slightly flares the case mouth to prevent shaving off jacket material or crumpling the case when seating a bullet.

One die set can also be used to handload several cartridges such as the .38 Special and .357 Magnum cartridges. The same goes for .44 Special and .44 Magnum cartridges and the .40 S&W and 10mm Auto. All that is required is adjustment to properly flare case mouths, seat bullets to a specified depth and apply a proper crimp.

When a cartridge is fired it expands to seal the chamber. Sizing fired cases lengthens their necks because the brass flows forward. Cases from nearly every factory rifle I have shot over the years have stretched past their maximum length the first time they were sized. A distance of only .01 inch from trim length to maximum length seems small, but a cartridge with a case over that maximum length will pinch into the front of the chamber, and on firing the mouth cannot expand to release the bullet. The result is excessive chamber pressure, something a handloader should obviously try to avoid.

Most new handloaders use a manual lathe-type trimmer when starting out, like the Hornady Cam Lock trimmer. If your hand cramps after turning the handle

A deburring tool removes brass burrs on the case mouth created by the trimmer. Double-ended hand tools make short work of this drudgery with outside and inside deburring tools and small and large primer pocket cleaners. Some of these allow the bits to be stored inside the handle. If your hands tend to cramp up, consider an electric tool like the Lyman Case Prep Xpress or Hornady’s Lock-N-Load Case Prep Trio.

Weighing Powder

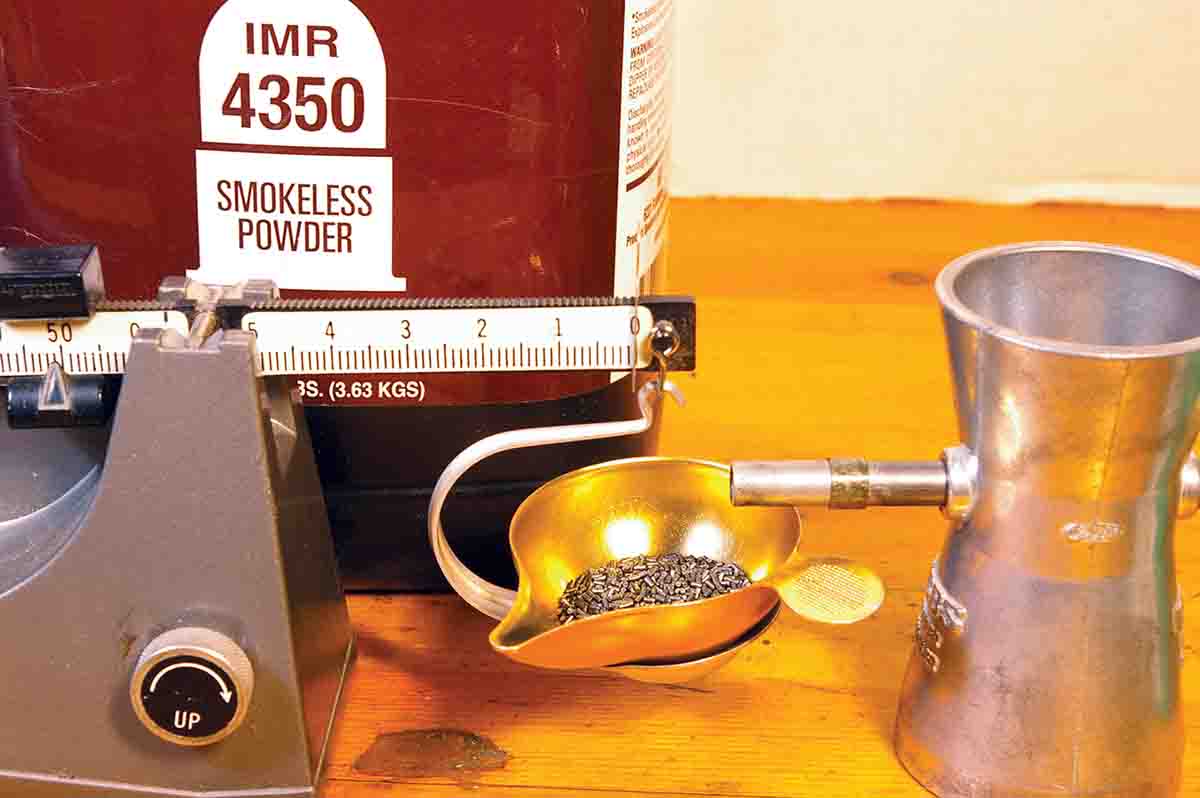

Powder charges must always be weighed. A balance beam scale is the traditional instrument to weigh powder, and it weighs powder to within .1 grain. Choose one with a 500-grain capacity, because eventually it will be used to weigh bullets and cases.

Expensive electronic scales weigh powder precisely, but more money will be tied up in such a scale than all your other reloading equipment combined. Sharpless is skeptical about how precisely inexpensive electronic scales weigh powder. “Electronic scales measure by pressure, not weight,” he said. “If air pressure changes, so do powder charge weights. A balance beam scale gives you true weights.” A powder trickler conveniently dribbles the last few granules of powder into the scale pan to bring the charge up to the correct weight. Make sure the trickler’s tube is long enough to reach the powder pan if using an electronic scale. A powder funnel with a wide spout to fit a variety of case mouths is essential for pouring powder into cases.

Weighing each powder charge for big batches of handgun cartridges is tedious. Sharpless recently loaded 200 9mm Luger cartridges. “I’d have been there all night weighing powder for each case,” he said. Instead, he saved time by adjusting his powder measure to drop a charge of HP-38 powder in the cases. He checked the weight of every tenth throw of powder on a scale to make sure they remained unchanged. With all the cases filled with an exact amount of powder and standing in loading blocks, bullets were seated to complete his handloads.

Take a moment to admire the first finished cartridge removed from your press. It represents the learning curve of following instructions and proper use of basic tools. Ensuing cartridges will soon pay for your reloading tool investments and be the start of an enjoyable hobby.