.284 Winchester

The Phoenix of Rifle Cartridges

feature By: John Barsness | February, 22

This was because 1955’s Model 88 had been designed around the .308, along with the first commercial .308 variations, the .243 and .358 Winchesters. Its one-piece walnut stock and sleek “hammerless” action, designed for easy scope mounting, supposedly appealed to “modern” hunters, rather than traditionalists who stuck with iron-sighted, outside-hammer, tube-magazine lever rifles. The similar Model 100 semiauto appeared in 1961, also chambered for the .243, .308 and .358 Winchesters.

To attain .270 ballistics required more powder capacity than the .308, so Winchester created a slightly fatter and longer case. Its rim was the same diameter as the .308’s – and the rims of the .30-06 and 8x57 Mauser, the case the .30-06 was based on. However, the .284’s case in front of the extractor groove measured .500 inch, tapering only slightly to a steep 35-degree shoulder.

This approximates the present trend toward shorter, sharper-shouldered “accuracy” rounds. At the time, the .284 was considered somewhat odd, but it did increase powder capacity approximately 20 percent over the .308 and allowed .284 cartridges to function in the 88 and 100 magazines. (At least it did most of the time. Handloader’s Ken Waters found the .284 fed erratically in his 88.)

All this occurred due to changes in the hunting rifle scene during the post-World War II economic boom. Some marketing theorists claimed hunters who used the semiautomatic M1 Garand during the war, would prefer quick repeat shots – and follow-up shots were a staple of pre-war hunting for white-tailed deer.

The .284’s two factory loads were Winchester Power Point spitzers, a 125-grain bullet at a listed 3,200 feet per second (fps) and a 150 at 2,900 fps. Back then, factories mostly used 26-inch barrels to chronograph ammunition and the 22-inch barrels of the 88 and 100 resulted in somewhat slower velocities – though not by much. My SPEER NUMBER 6 MANUAL FOR RELOADING AMMUNITION, published in 1964, lists the velocities of factory ammunition chronographed in its lab. Winchester’s 125-grain .284 load got 3,067 fps and the 150 2,811, both from a Model 88.

By the 1960s, most hunters used scopes, and often shot deer at longer ranges. Whitetails reproduce rapidly if given the chance and were more abundant. Hunters started sitting still more often, whether near natural openings or in elevated stands. Better scopes also allowed more accurate shooting in the dim light around dawn and sunset, when whitetails tend to move. Thus the new trend (which continues today) turned out to be more precise shooting at stationary deer, rather than faster repeat fire.

While the 88 and 100 looked modern, their trigger pulls and accuracy were generally inferior to bolt actions. I know this partly due to once owning an 88 in .308 Winchester, one of the world’s most accurate big-game cartridges. With factory and handloaded ammunition, three-shot groups averaged 1.80 inches – plenty for woods deer, but not nearly as accurate as typical bolt-action .308s. Winchester discontinued both rifles after 1973, and never did chamber the .284 in a bolt action, even after short-action Model 70s appeared in 1984.

The .284 became primarily a cartridge for rifle loonies, though many believed the .284 was severely handicapped because its deep-seated bullets reduced powder room. I can specifically recall reading at least three magazine articles about the potential of the .284 in longer bolt actions (including one by Ken Waters) with the “bullets seated out where they should be.”

Back then, many handloaders believed bullets “protruding” below case necks reduced powder room considerably, and increasing powder room would result in a similar increase in muzzle velocity. This is not true at the same pressure; instead, the velocity gain is approximately one-fourth as much as powder capacity. This is easily demonstrated by comparing the .308 Winchester with the .300 Remington Ultra Magnum (RUM), which has almost exactly twice the powder room: The .300 RUM does not double the velocity of the .308; instead it gets about 25 percent more.

Back then, the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) used copper-crusher equipment for measuring pressure. Today, SAAMI has transitioned to piezoelectric transducer testing, though it still lists both CUP (copper units of pressure) and psi (piezoelectric transducer) pressures for many rifle cartridges. The present SAAMI CUP Maximum Average Pressure (MAP) for the .284 is 54,000, and the piezoelectric MAP 56,000 psi. They also list the standard muzzle velocity of 125-grain factory loads as 3,125, and 150s at 2,845, recorded 15 feet from the muzzle from 24-inch barrels.

These are relatively low pressures and velocities compared to similar bolt-action cartridges, especially the .270 Winchester. The .270’s piezoelectric MAP is 65,000 psi (as high as SAAMI allows for any rifle round), and the top factory ammunition velocity allowed with 150-grain bullets is 3,000 fps.

My only experience with Winchester .284 factory ammunition occurred in 2009, while briefly owning a Savage 99-C. (Apparently, Savage was the only other American firearms company to offer mass-manufactured .284s during the cartridge’s early years.) I bought 150-grain ammunition at a local store, which averaged 2,669 fps when chronographed 15 feet from the muzzle. However, handloads with 150-grain Sierras and Hodgdon’s maximum listed 150-grain load of 59 grains of H-4831 got 2,826 fps from the 99’s 22-inch barrel, very similar to Hodgdon’s listed 2,852 fps from a 24-inch barrel.

Despite being a fan of Savage 99s, the 99-C was a later tang-safety model with a detachable magazine and Monte Carlo buttstock. While accurate enough, it weighed around 8.5 pounds with a lightweight scope. The trigger pull also wasn’t great and far less easily fixed than the original trigger.

The .284’s first revival occurred primarily in short-action bolt rifles, usually designed to save weight compared to long-action rifles in, say, .270 Winchester. Robert-Chatfield Taylor, a part-time gun writer, had Griffin & Howe build a .284 with a fancy walnut stock on a short Remington 700 action. As Jack O’Connor pointed out in The Hunting Rifle (1997), “It was to be the lightest, deadliest, mountain and saddle rifle in captivity. As it turned out, however, it weighed with scope exactly the same as his .270…. I am doubtful if it was worth all the trouble.”

In reality, short-bolt actions don’t save much weight. The short 700 action, for instance, weighs 35 ounces, only 3 ounces less than the long action – and less than walnut stocks vary in weight. However, there are other ways to save serious ounces and in the 1980s, a West Virginia gunsmith decided to make his own actions and synthetic stocks, both designed to be lighter, yet very strong. In the action, this was accomplished by putting steel in the locking lugs, where it mattered, and minimizing it elsewhere.

Melvin Forbes’ short action weighed only 20 ounces, including the magazine, which he made a full 3 inches long, about 0.2 longer than the 700s. The first rifle he built was a .284 Winchester, which weighed less than 6 pounds with a light scope and a 22-inch Douglas barrel. His Ultra Light Arms rifles were among the forefront of the “new” mountain rifle movement, and the .284 remains one of the more popular chamberings.

However, by then, there wasn’t much demand for .284 factory ammunition or brass, and Winchester had started running its case-forming dies longer than with more popular cartridges. Brass quality suffered, and while it could be “uniformed” by a knowledgeable handloader, for average handloaders, accuracy tended to be so-so. Forbes started advising potential .284 customers to order a 7mm-08 Remington instead, because good-quality factory ammunition and brass were readily available.

However, eventually that changed. First, Norma adopted one of many .284-based wildcats as a factory round, naming it the 6.5-284 Norma. The case had exactly the same dimensions as the popular 6.5-284 Winchester wildcat, but the Norma’s overall length is 3.228 inches, allowing bullets to be “seated out where they should be.” The Norma brass was very good, as was 6.5-284 brass made by Lapua and could be easily necked up to .284. This resulted in the odd reversal of buying 6.5-284 brass to make .284 cases.

Another brass breakthrough resulted due to the popular target sport F-Class, which involves shooting at 1,000 yards from prone with a bipod. “Open” F-Class rules allow any rifle cartridge up to .35 caliber, and while the 6.5-284 Norma proved plenty accurate, it resulted in relatively short barrel life. Some shooters started using the standard .284 instead, which extended barrel life and proved popular enough for brass manufacturers such as Lapua and Peterson to start making high-quality .284 cases.

I decided to try a .284 again one day while talking with Tyler Hansen, a top-notch gunsmith for Capital Sports in Helena, Montana. I asked if the gunsmithing department had a .284 reamer, and Tyler smiled and said yes. I decided to have him rechamber the semi-custom 7mm-08, based on a short Ruger 77 tang-safety action, mentioned in “Mystery Rifles,” an article in Rifle No. 314 (January-February 2021).

However, the present handloading component/equipment shortage had begun, and neither .284 brass nor dies could be found. However, I did find 100 Lapua 6.5-284 cases in another local store, no doubt still hanging around due to “sticker shock,” since the price was $100.

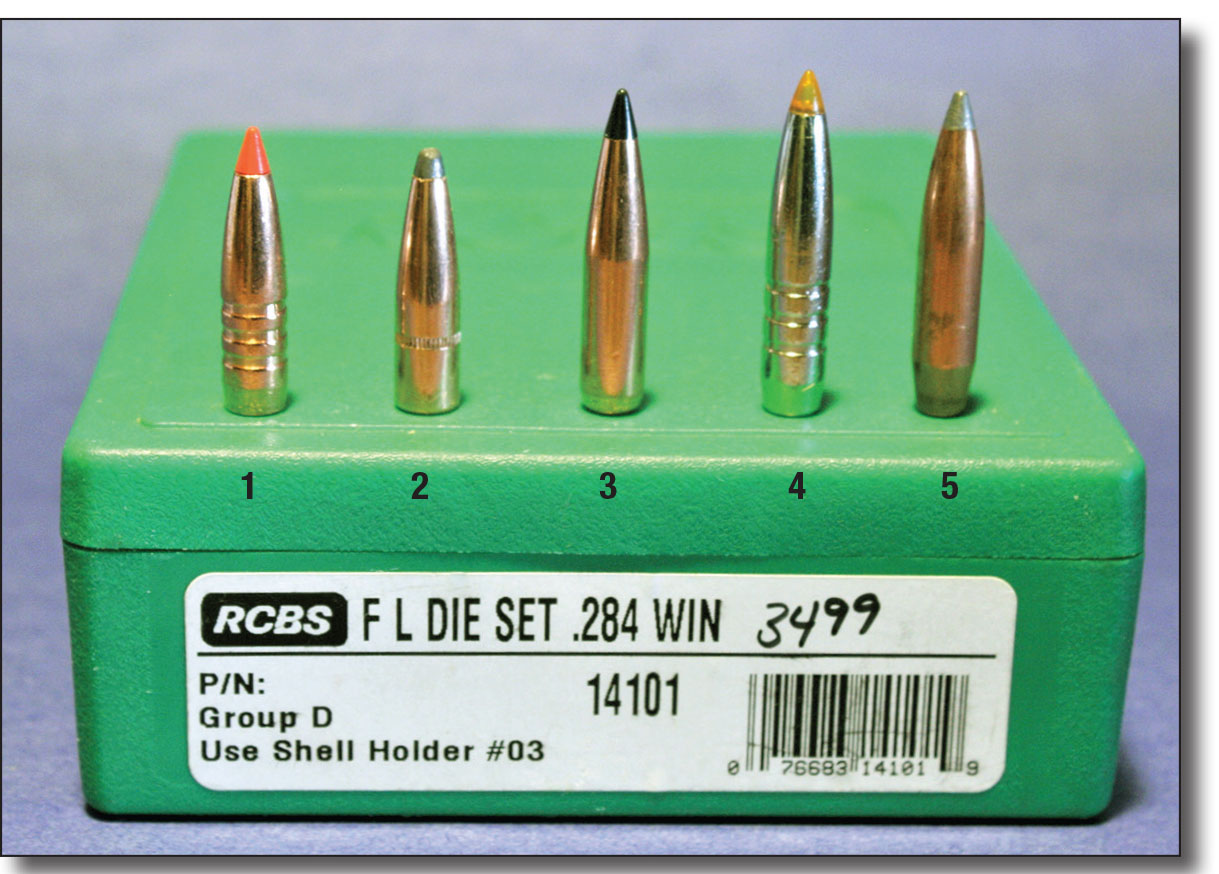

After finding the brass, I posted an ad for a set of .284 dies in the “Free Classifieds” in a chat room. One of my fellow members, David Walter, offered to send me a set of RCBS dies free, because I had helped him out a few times.

The RCBS expander ball was used to open the necks after inside chamfering the case mouths and applying Redding Imperial Sizing Die Wax. They resulted in good accuracy even on the first firing, though groups shrank slightly when using fired brass.

The handloads tried were selected by checking all available current data for powders producing the highest velocities with various bullet weights. This brought up a difference between American and European data: While the standard SAAMI maximum average pressure is 56,000 psi, the .284 maximum for the European equivalent of SAAMI, the Commission Internationale Permanente (CIP) is 63,817 psi – probably partly because of a distinct lack of Winchester 88s and 100s east of the Atlantic Ocean.

While some handloaders claim SAAMI and CIP pressures differ due to the different location of the transducer in CIP pressure barrels, my friends at Western Powders in Miles City, Montana, ran an experiment some years ago. They plugged the transducer hole in one of the SAAMI barrels they made in their shop, then redrilled the barrel with the CIP placement. There essentially was no difference in pressures with the same loads.

After shooting some .284 handloads, I compared the water capacity of the fired Lapua brass with a fired .280 Remington case, using 139-grain Hornady and 175-grain Sierra bullets seated to overall SAAMI length. (This is the most accurate way to measure powder capacity, NOT filling the case to the mouth.) The .280 held 4 percent more water, which translates to a 1 percent gain in muzzle velocity, about 35 fps with loads getting around 3,000 fps.

My rechambered .284’s 22-inch barrel tends to produce close to same velocities as published data from 24-inch barrels – something it also did as a 7mm-08. The only listed load resulting in any traditional “pressure” sign was a maximum Vihtavuori N560 charge and the 175-grain Sierra GameKings, which left a slight impression of the ejector hole on the case heads. The listed load is 1.4 grains below Vihtavuori’s maximum.

Accuracy remained the same as before the rechambering, with three-shot groups averaging around .75 to 1.5 inches. This may not seem very good to those handloaders with rifles that shoot “half an inch all day long,” but with a 12-ounce Swarovski 3-9x 36mm scope in Ruger factory rings the rifle weighs 7 pounds, 10 ounces, a fine weight for all-around big-game hunting in Montana and many other places on planet Earth.

.jpg)