70 Years and Counting

The .222 Remington is Not Old Yet

feature By: Terry Wieland | February, 22

The .222 Remington is now 70 years old – venerable by any standard except geologic time – and its praises have been sung (by my count) by three generations of writers. It’s unquestionably the most influential small-caliber rifle cartridge of the twentieth-century, ranking with the .30-06 and .375 Holland & Holland in terms of impact and progeny.

That being the case, one wonders, what on earth is left to say about it? The truth is, not much, except that many of today’s riflemen, especially new shooters, probably have not read everything that’s gone before. In fact, many have either never heard of the .222 or dismissed it as an octogenarian has-been. If that’s the case, they’re missing a bet, because the .222 Remington is one of the sweetest little numbers ever created, still excellent for a range of uses, some of which did not even exist when Remington unveiled it in 1950.

The .222, or “triple deuce” as some “slangsters” like to call it, was introduced into a world that was vastly different than today. Even five years after the end of the war in Europe, American factories had still not returned to full civilian production, and shooters had a vast appetite for anything that would go “bang,” as well as the wherewithal to keep doing so.

The 1930s had seen a proliferation of what were then termed “varmint” cartridges, the varmint in question being primarily the eastern woodchuck. The fad for high-velocity .22 centerfires began with the .22 Hornet in the 1920s, and went on to include the .220 Swift and a rash of wildcats. All had one problem or another. Some had rims, which were old-fashioned; others were chambered in rifles with tubular magazines, requiring ballistically-inferior flatnose bullets; as for the Swift, the cartridge that broke the 4,000 feet per second (fps) barrier, it was just too much for most shooters: Too loud, too powerful, too hard on barrels.

When the dust settled after the war, Remington decided to start with a completely clean slate and design a brand-new cartridge and a modern, accurate rifle to go with it. Remington designer Mike Walker was put on the project, and after looking at what was available as a “basic” case to start from, decided to design one that was completely new. The result was a trim little rimless cartridge, with slight body taper, a sharp shoulder, and enough neck to hold bullets firmly without crimping. Many have called it a scaled-down .30-06, and the comparison is not inapt, as the accompanying photograph shows.

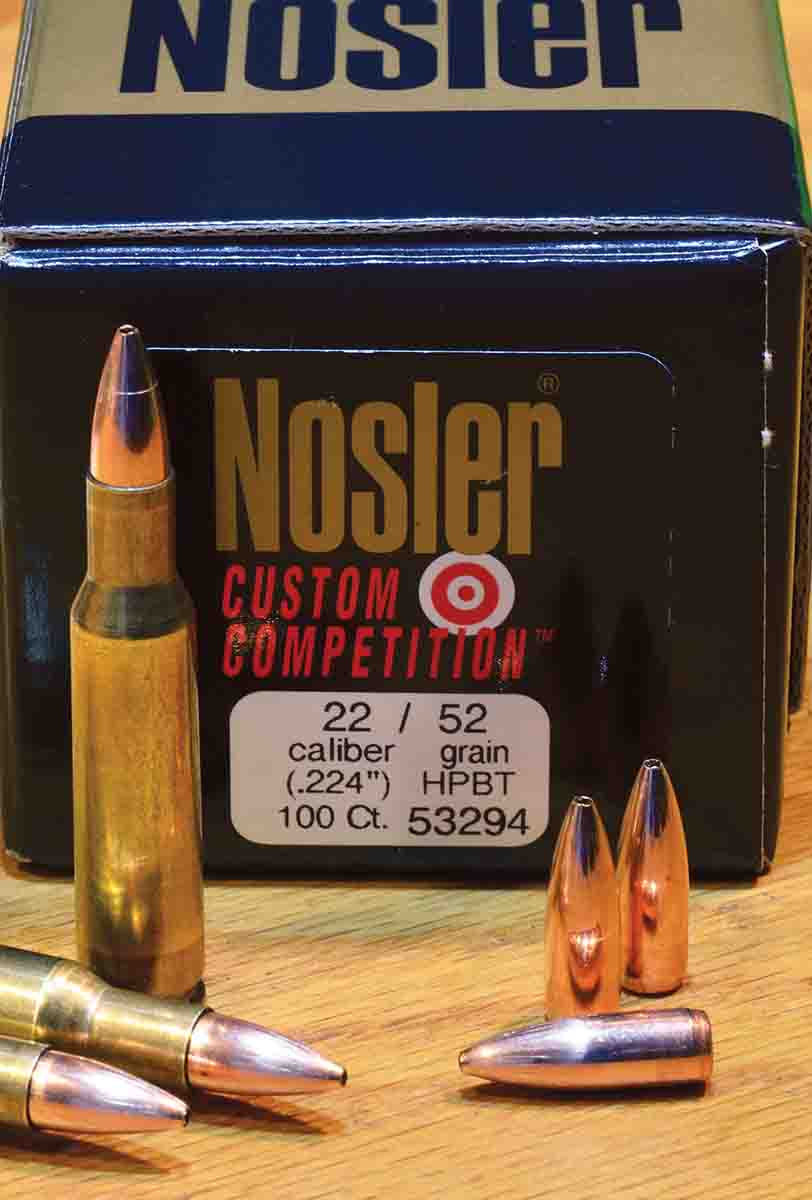

Unsurprisingly, the new cartridge had some teething problems. Its original 48-grain bullet was prone to ricochets. Remington thinned the jacket, which allowed more room for lead, and the resulting bullet weighed 50 grains. That became the standard, and the usual touted velocity was 3,200 fps. Some loads were slower, others faster, but 3,200 was the benchmark.

Not coincidentally, Mike Walker was one of the prime movers in the sport of benchrest shooting, then in its infancy, and the .222 Remington quickly established itself as the king of benchrest. For the next 25 years, it was noteworthy if someone won a match with anything other than a .222. It was not finally dethroned until the early 1980s, with the development of the 6 PPC.

Meanwhile, the little cartridge had fathered the longer .222 Remington Magnum (1958) and .223 Remington (around 1960) and the shortened .221 Fireball (1963). These in turn went on to be necked up, down, and sideways to create a host of wildcats and factory rounds. The .223 was adopted as a military cartridge in the AR-15 and is still the most common chambering in that rifle.

In Finland, a largely unknown company called Sako had introduced a short bolt action in 1949. Originally intended for the .22 Hornet, the Sako Vixen (L46) proved to be ideal for the .222, and it was available as a finished rifle or as an action or barreled action for custom gunsmiths. The Vixen in .222 established Sako as a high-end player in the accuracy game.

It also introduced Americans to the (now) fabled Sako trigger – easily the best factory trigger available for many years. It has been likened to a “glass rod breaking” by more writers in more publications than one could count. Whoever came up with it, it’s a perfect description. The Sako trigger became such a selling point, it prodded American gunmakers to improve their own triggers, as well as encouraging independent makers to provide replacements. Even the best of these – Timney, Miller, Dayton-Traister, you name it – were hard-pressed to match the factory Sako.

European hunters took to the .222 Remington, but not for benchrest or varmint shooting, neither of which is very common there. They found it was a perfect cartridge to chamber in a compact, easy-to-carry rifle for two species that cause European hunters to swoon: capercaillie and roe deer.

The capercaillie is a huge member of the grouse family, traditionally still-hunted and shot with a small-caliber rifle while perched in a tree. To European hunters, they are a big deal: In the 1980s, the trophy fee for a capercaillie in Austria was $25,000! Roe deer, like chamois, constitute almost a religious object in Alpine hunting, shot at close range from a blind. They are little bigger than a well-fed coyote, and require precise shot placement, but not a great deal of power.

Previously, two other American cartridges had been eagerly adopted for this purpose: first was Savage’s .22 High Power (1912), and a few years later, the .22 Hornet. Both were rimmed cartridges that work beautifully in the double rifles and single-shots preferred by traditional Europeans. They gave them metric designations (5.6x35R for the Hornet, 5.6x52R for the .22 HP) and chambered them in a wide range of rifles. Both brass and ammunition are still produced in Europe.

By 1950, even the most traditional of European hunters were ready for something new, given the disruption and dislocation of the war and its effects on rifle and ammunition makers. Since that something would most likely be a bolt action, a rimless cartridge was preferable and the .222 Remington was ideal. Along with the Sako Vixen, other companies that began chambering it included Steyr in Austria and Brno in (then) Czechoslovakia. Norma, RWS and others began making ammunition.

For hunting roe deer and capercaillie, a bullet requires different characteristics than one for woodchucks, prairie dogs or crows. For roe deer, a bullet must penetrate to the vitals and not destroy much meat; for a capercaillie, which might become a full-body mount, a precise shot is required with a minimum of damage. European hunters were not looking for maximum velocity; in fact, a little lower velocity was sometimes preferred. European bullets were less explosive than American varmint bullets, and the cartridge was sometimes loaded with 52- or 55-grain bullets, including some full metal jackets.

From the beginning the favorite powder for the .222 Remington was 4198, either IMR (introduced in the 1930s) or Hodgdon’s (1946). The two were identical, since Hodgdon was repackaging surplus IMR. Modern H-4198 is newly manufactured, however, and is rated slightly faster than IMR-4198. This is something to keep in mind if using older load data.

Another wrinkle is that sometime in the early going, Remington decided to strengthen the .222 case by thickening the walls. This reduced powder capacity, which in turn produces higher pressures with the same load. The date of this change is vague. I have also found variations in case capacity from one manufacturer to another, and even in cases from the same manufacturer. For all these reasons, anyone starting to load .222 Remington with older data is advised to start at the bottom and work up.

Over the years, various writers have found other powders to be superior to 4198 in the .222, but these always seem to disappear into the netherworld of the “discontinued” list (Herter’s 102 and 103, for example, and a couple of early Norma numbers) while 4198 soldiers on. It’s safe to say that 4198 is never a bad place to start.

Still, newer powders do offer some advantages, whether or not they are more accurate. For example, 4198’s long, extruded grains do not meter terribly well. Hodgdon H-322, which became the darling of the benchrest crowd in the 1980s, shouldering 4198 aside, has shorter grains and meters beautifully. So does CFE 223 and IMR-8208 XBR, which is super short. Hodgdon Benchmark, which as the name implies, was intended for benchrest shooting, is another strong candidate.

One drawback of 4198, not surprising in an 85-year-old powder, is that it has no particular resistance to changes in temperature. If you work up a winning benchrest load in Maine in November, and then enter a match in Phoenix in May, it’s not likely to perform the same way. Of the alternatives suggested, IMR-8208 XBR is the most temperature-stable and consistent.

CFE 223’s big advantage is reducing cuprous fouling – a consideration for anyone intending to go West and fire thousands of rounds at prairie dogs.

For my part, in the past I’ve had great luck with Vihtavuori N120. In fact, the company recommends it specifically with a Lapua 55-grain FMJ bullet for birds like capercaillie. “We guarantee it’s a winner,” says the company, in writing. Can’t argue with that. Also, it’s especially good with short or light-barreled hunting rifles. Alas, I had no VV-N120 to include here.

A quick glance over several loading manuals of varying vintages found that, over the years, “accuracy” recommendations have included Hodgdon BL-C(2), 4895 (both IMR and Hodgdon), IMR-3031 and IMR-4320 among others – and this is just for 50- or 52-grain bullets. Obviously, over its lifetime, everything has been tried and it has proven to be extremely tolerant of different powders.

The accompanying table does not show every powder I’ve tried, only the ones that worked best in my current test rifle, a Blaser R8. As can be seen, the accuracy results are very uniform. Most of the loads are maximum, according to Hodgdon data, and no attempt was made to tailor a super-accurate load for that rifle.

The Blaser would be just about ideal for both capercaillie and roe deer, being superbly engineered, beautifully made, and with an extremely ergonomic (if rather futuristic) composite stock. My major complaint about composites over the past 35 years is that advertising claims aside, most are not ergonomic. Blaser has conquered that problem.

As for North American game for a .222 Remington, I can think of few things better for pursuing the current “most wanted” varmint, at least where I live, and that’s the armadillo. In fact, armadillos are increasing all over the south and moving rapidly north, devouring quail, grouse and pheasant eggs as they go. Just a hint. The eastern woodchuck may no longer occur in the numbers it once did, and few people shoot crows out of trees anymore, but the armadillo will do, and gives an excellent excuse for carrying a neat rifle when going for a walk in the woods.

There are few neater rifles, historically, than the .222 Remington. In a country which is increasingly populated, and where noise and ricochets are an issue, the “triple deuce” (forgive me, I had to call it that at least once) is just about ideal, and it can be found in some seriously fine rifles, old and new.

.jpg)