Mike's Shootin' Shack

When to Slug Barrels

column By: Mike Venturino | February, 22

There are two questions involved. One is, “How to slug barrels?” The second is, “When to slug barrels?” On the surface, slugging barrels seems easy. Simply drive an oversized soft piece of lead down the rifle or handgun barrel. Actually, this should be done with some finesse lest a barrel is damaged along the way. We’ll return to that process shortly.

Upon purchasing my very first centerfire revolver, an S&W K38, I asked the fellows at my local gun club whether I should slug its barrel. After all, my brand new Lyman manual gave instructions on how to go about that. Those older gents laughed and in essence said, “Don’t worry about it. Smith & Wesson’s barrels are all the same per caliber. Besides, they have an odd number of grooves (five) so it is difficult to measure them unless you have a V-block and a solid grasp of mathematics.” I had neither, so for 55 years I’ve shot all smokeless-era S&Ws with nominal cast bullet diameters as in .358 inch for .38/.357 and .430 inch for .44 Special/.44 Magnum. With good quality handloads, accuracy has always been superb.

If your rifle or handgun is made by an American manufacturer of known reputation, its barrel bore dimensions will likely be right at its nominal specs. I feel this is also true for Italian and Japanese replicas of vintage American firearms. There is one exception to that. I’ve found that ’73 Winchester replicas coming from both those countries use .429-inch barrel groove diameters in their .44-40s. Winchester’s original ’73s and ’92s used .427 inch as their nominal specification. (I should note that very early ’73 Winchester barrels could vary widely. I’ve measured them from .425 to .433 inch and above.)

For example, if someone gets a Shiloh Model 1874 or 1877 Sharps from my friends over in Big Timber, Montana, you can bet the barrel’s land and groove diameter is going to be .400/.408 inch for .40 calibers and .450/.458 inch for .45s. If you purchase a Colt SAA made in the twentieth- or twenty-first-century, its barrel groove diameters will be .451/.452 inch for .45s and .426/.427 inch for .44s. On a below-zero Montana day a few years ago, I spent hours in my gun vault slugging all my .44 and .45 Colt SAAs. They varied in manufacturing years between 1904 and 2008. Those were my results. (I cannot say the same for Colt SAAs’ cylinder chamber mouths. They are apt to vary significantly.)

As for vintage military rifles, I’ve never slugged any of my Model 1903s or 1903A3s. Fired with .310-inch cast bullets, all have given suitable groups, likewise with my German K98ks. They have been fired with .325-inch bullets with fine results. I cannot say the same for my British, Soviet Union or Japanese made military rifles. Some have shot initial cast bullet loads well and some just tumbled bullets. I had a Finnish Mosin Nagant Model 39, which consists of a Russian-built action fitted with a Finish barrel by Sako on that particular rifle. It perhaps was the most accurate cast bullet military rifle of my experience. Its barrel groove diameter was said to be .310 inch and it shot .310-inch bullets almost to MOA groups from the very beginning.

Let me give a recent example of “shoot before slugging.” Recently, I was chronographing two Colt SAA .38-40s, one made in 1904 and one made in 1994 as confirmed by factory letters for each. The 1904 specimen gave velocities from 50 to 100 feet per second slower than the more recent one. My first thought was that perhaps its barrel groove diameter was a bit oversized as is sometimes the case with vintage .38-40s. Instead, I stuck it in my Ransom Pistol Machine Rest. It fired 17 five-shot groups at 25 yards with the average being less than 1.90 inches. Slugging the barrel wasn’t even considered then. Checking the barrel-cylinder gap showed why velocities were so different. The older .38-40 had a .011-inch gap to the newer one’s .005-inch gap. That reinforced my idea of shoot before slugging.

Here’s an instance when I doubted factory specifications. Some years back, I read where .38/.357 Colt barrels were nominally .353/.354 inch across their grooves. I said, “Huh, everyone knows that .357 inch is proper for .38 Specials and .357 Magnums.” So I slugged a Colt Detective Special from 1962 and a Colt SAA .357 Magnum from 1970. Sure enough their slugs were .354 inch. I can’t help but wonder how the “new” Colt Python .357 Magnum barrels slug?

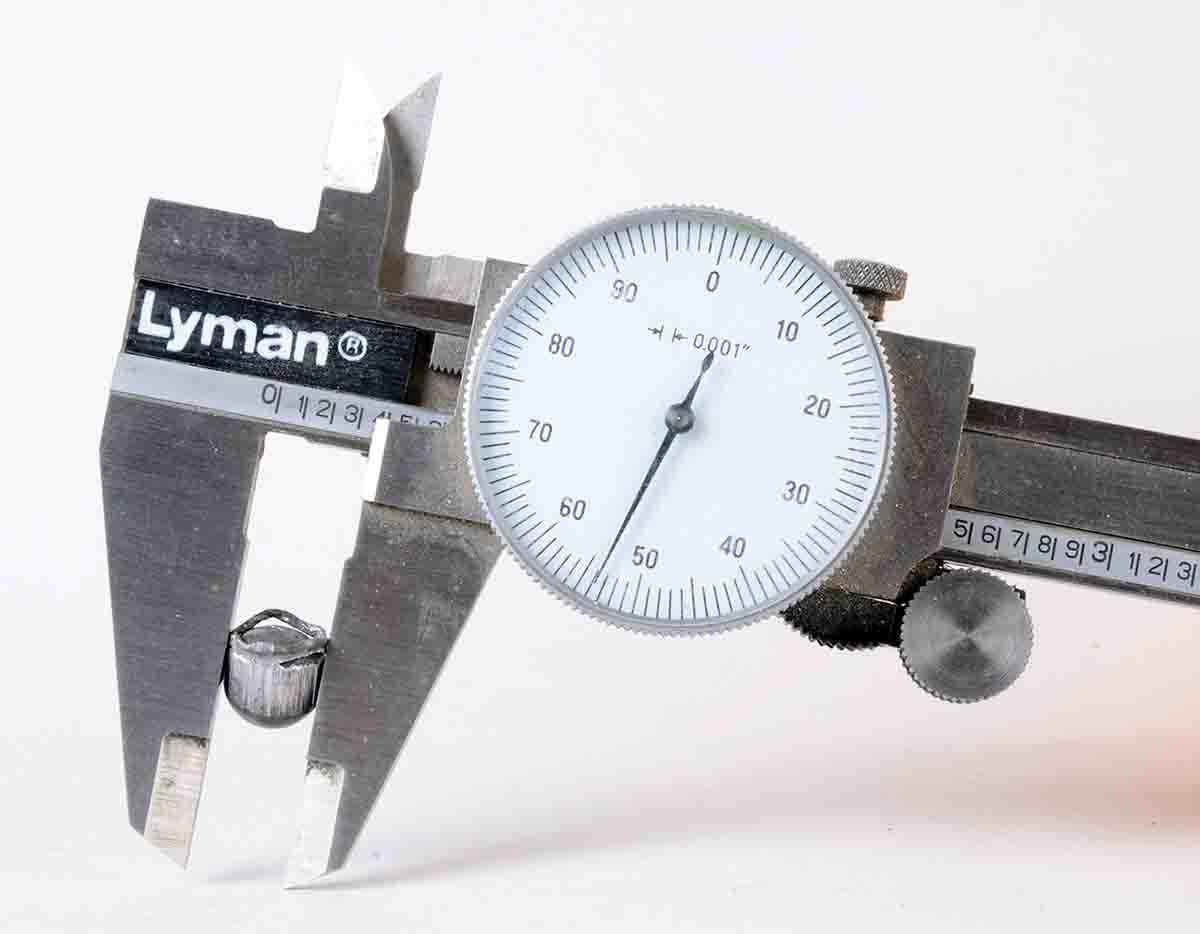

However, when slugging a barrel is necessary, it should be done with care. For slugs, I keep on hand a variety of Hornady and Speer pure lead round balls as intended for muzzleloaders and cap-and-ball revolvers. For example: if I’m slugging a .44-40, rifle or revolver, I will use a .454- to .457-inch roundball. It is tapped until flush into the firearm’s muzzle using a plastic or wooden mallet. This will leave a ring of lead at the muzzle, and using a large slug ensures its sides are parallel for accurate measuring. Once the slug is flush at the muzzle, it is then tapped about 6 inches further into the barrel using a short piece of hardwood dowel. Then it is pushed on through with a suitably long piece of dowel of the proper caliber.

With modern-made barrels, I have encountered some that had tight and loose spots. A slug might be sliding easily and then come to a stop, only to be pushed further by some considerable “taps” on the wooden dowel. In a couple of instances, there were about a half dozen such spots. Incredibly, in my thinking, those barrels shot cast bullets very well if they were matched to the slugs’ diameters. Another bit of advice is to catch the slug when it exits from the barrel’s breech end. Falling out on a concrete floor does nothing for close measurements. For slugging semi-auto handguns such as the Model 1911, it’s far easier to work with them dismounted.

My final word is, “Shoot first, slug second and then slug carefully.”