Cartridge Board

Evansville Chrysler World War II Steel-Cased .45 Auto (ACP) Ammunition

column By: Gil Sengel | February, 22

Within a week, the Evansville plant was approved for conversion to produce 5 million .45 Auto rounds daily. Chrysler engineers were then sent to the Frankford Arsenal to study its production methods and scale them up to reach their goal.

Immediately problems arose. All brass rolling mills were operating at capacity. They produced the brass sheet from which cartridge cases (and many other things) were made. In the spirit of the time, Chrysler was told to convert the plant; the brass would be found somehow.

Engineers had just gotten to Frankford when the Ordnance Department (OD) increased its order to 7.5 million rounds daily. Then, the following day, another phone call raised this to 10 million rounds. The reason for the increase was said to be the possibility of a land invasion on the East or West coast. No one mentioned where the guns to fire all this ammunition were going to come from! After the war, it was learned that the Japanese believed an invasion would fail because of all the hunting rifles in civilian hands.

Ninety days later, on June 30, 1942, EC test-fired the first full production .45 Auto cartridges. Brass was still almost impossible to get. The next day, representatives from the OD told Evansville Chrysler to continue brass production, but to immediately develop a steel case. This had probably been the plan all along because when the war started, the Frankford Arsenal began development of a steel .45 Auto case. By June 1942, steel cases were proven possible, but problems of cracking, splitting, failure to eject and corrosion remained.

Evansville Chrysler also tackled the corrosion problem. Frankford used zinc plating, then a wash coating of something called Cronak (sometimes spelled Kronak). EC found a double coating of Cronak worked better, though experimenting continued throughout the war.

Of more importance was the ammunition shipping container. At first, this was 50-round boxes inside a large, double-dipped, waxed paper box inside a wooden crate. This failed to stand up to shipping by sea, then the South Pacific heat and salt air when off-loaded onto beaches. General Douglas MacArthur wanted something better, so the army asked Evansville Chrysler if it could solve the problem. The answer was again “Yes.” A heavy gauge can made by American Can Company and hermetically sealed was quickly designed. It opened with a “key” like the later canned ham.

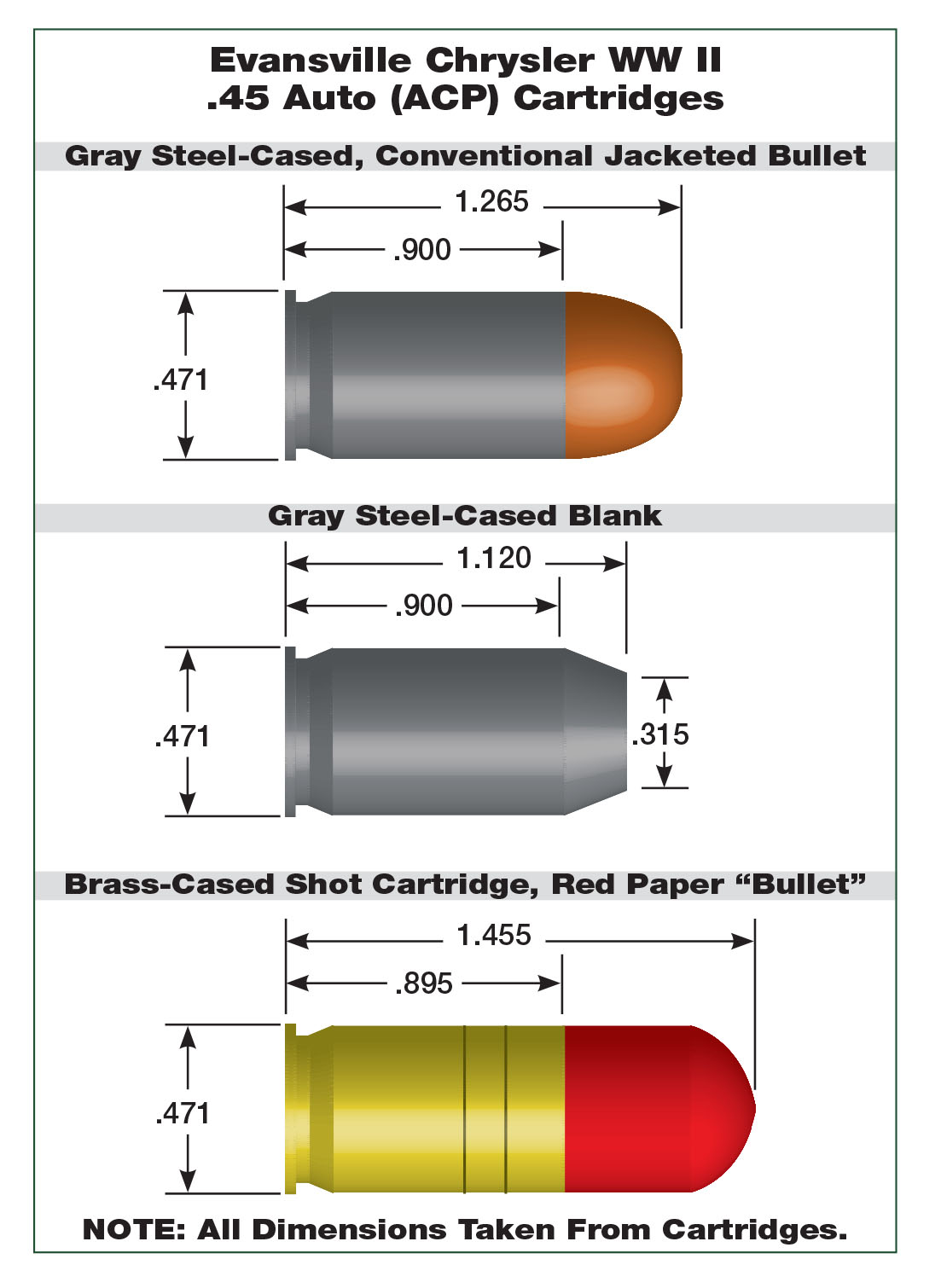

While all this was taking place, EC was asked if it could make 5,240,000 .45 Auto shot cartridges to be included in aircraft emergency survival kits. This was November 1943, with expected delivery by December 31! Fortunately, no development work was needed because the design had already been done by Remington. It consisted of a standard brass case (per U.S. Army Air Force) and a red waxed paper “bullet” containing 135 No. 7½ shot pushed by 6 grains of Bullseye pistol powder. The order was completed on time.

As if Evansville Chrysler wasn’t busy enough, later it received a request for 3 million blanks used by K-9 units to train the dogs not to fear gunfire. Next were 2 million dummy rounds, inert cartridges used for function testing when repairing arms. Both were completed quickly.

No space remains to cover the later manufacture of almost half a billion .30 Carbine brass- and steel-cased rounds. When asked to convert some of its machines, the first .30 Carbine cartridge was fired two weeks later! Nor can we cover the rebuilding of tanks and trucks used in training or firebomb production that occurred near the end of the war when ammunition needs could be cut back a bit.

Chrysler’s former auto plant produced nearly 3.5 billion cartridges for the war effort. If laid end-to-end they would circle the earth 2.8 times. The steel-cased rounds are seldom seen today, with most having been fired in anger and rusted into the sands of some now forgotten South Pacific island. Occasionally, single rounds are seen at gun shows. If so, pick it up. It was made at a time when America’s future was in grave doubt. The fact the little cartridge (and gun shows) exist today proves that we persevered. The lessons learned from this part of the past are of great value today.