.350 Legend

A Useful but Mysterious Cartridge

feature By: John Barsness | November, 22

This may seem puzzling to some of us, but almost every hunter has firm convictions about appropriate calibers, projectiles, etc. Game department bureaucrats are no different, though sometimes less ballistically sophisticated than the average Handloader reader. Some may even be victims of the Dunning-Kruger effect, a psychologically documented bias where people with limited knowledge greatly overestimate their own knowledge.

Even supposedly “wild Montana” contains several areas where high-powered rifles aren’t legal, including six square miles of public ground next to my small town, and for the same reason: The area borders the “city limits,” along with farms, ranches and subdivisions. Until recently, each of these rifle-free zones had different regulations, each being set by the local game warden. In our particular area, he proclaimed all saboted shotgun slugs illegal due to their higher muzzle velocity, when their low ballistic coefficient (BC) makes them no more likely to hit a distant human – or Hereford – than Foster slugs. (This responsibility was removed from the local wardens a few years ago, and now all such Montana areas have the same regulations.)

In 2014, Ohio finally allowed rifles chambered for “pistol” cartridges. In the state Department of Natural Resources regulations, these are defined as: “All straight-walled cartridge calibers from a minimum of .357 to a maximum of .50.” (One of the other oddities of the Ohio regulations is that such rifles are limited to a total of three rounds of ammunition in the chamber – though this does not mean their magazines can only hold two rounds. Instead, hunters are supposed to only load three cartridges, even if their rifle will hold far more.)

Some of the neighboring states also place restrictions on what “rifle” cartridges can be used on public land. For example, Indiana and Michigan have the same basic straight-case regulation as Ohio, but limit case length to 1.8 inches.

The .350 Legend was accepted as Ohio-legal, even though its bullets are not quite .357 inch in diameter. Instead, they measure .355, generally known among handloaders as 9mm. When Brian Pearce wrote his “Mostly Long Guns” column on the .350 Legend in Rifle No. 309 (March - April 2020), he asked Winchester about this, since originally the bullet diameter was supposed to be .357, “but no accurate responses were offered.”

I have my own notion on why this might have happened, which will be mentioned later, but if you Google “SAAMI cartridge drawing .350 Legend” on the internet, the official drawing from the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers Institute (SAAMI) appears, which shows bullet diameter as .357 inch. Yet, the two brands of factory ammunition purchased with my test rifle featured .355-inch bullets – as do the bullets listed in the small amount of pressure-tested .350 Legend loading data.

The rifle is a Savage Model 110 Apex Hunter XP, which happened to be sitting on the “new” rack at Capital Sports in Helena, Montana. I am always looking for new article ideas, so I phoned the Handloader editor from the store, asking if he’d be interested. (This is an old tradition. I first phoned the editor from Capital in 2010, asking if he’d be interested in an article on the then pretty-new 6.5 Creedmoor, since the store had several Ruger Hawkeyes that were selling quickly.)

Next, I broke down one round of each factory load, confirming both bullets were .355-inch in diameter. Slugging the Savage’s bore with a .357-inch cast bullet revealed the grooves spanned .355 in diameter, and the lands .348.

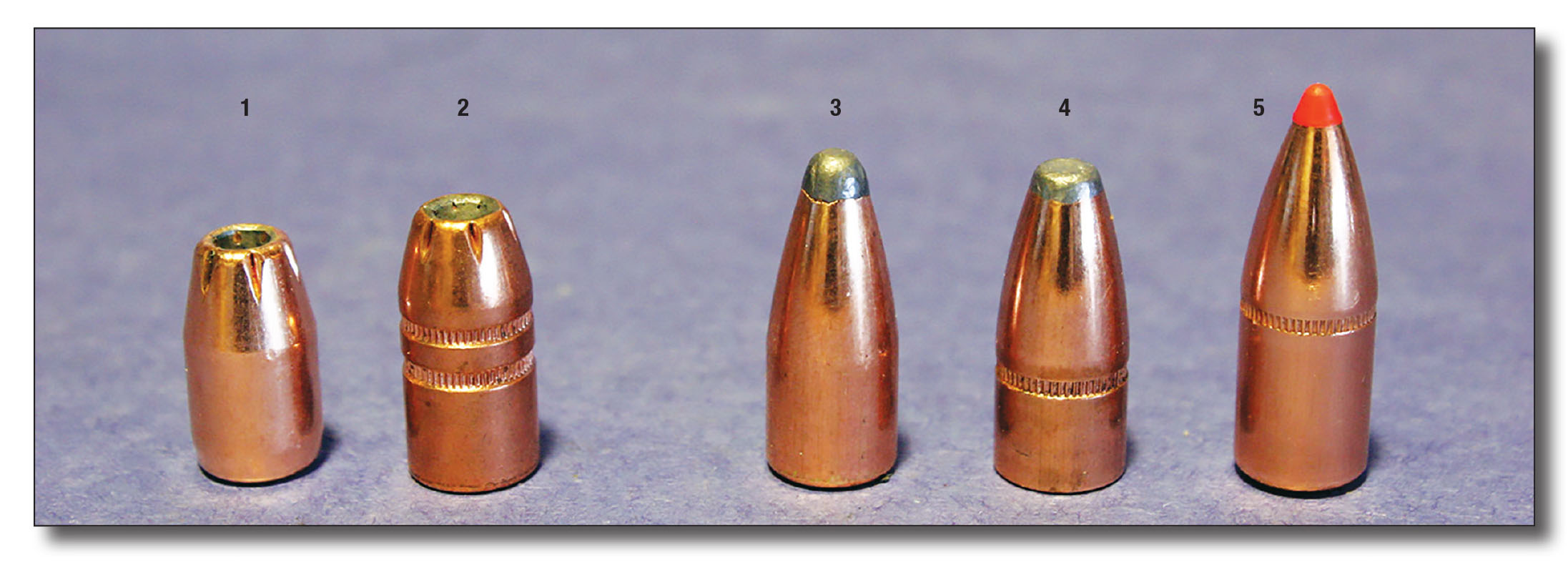

This choice of 9mm seemed very odd, especially since so many .357-inch handgun and .358-inch rifle bullets already existed. For years, one of my favorite .35-caliber hunting bullets has been Speer’s 180-grain Speer Hot-Cor flatnose, which has worked great in various moderate-velocity cartridges, expanding and penetrating very well on deer, even when started at less than 2,000 feet per second (fps).

I experimented by seating a Speer 180-grain bullet in one of the empty cases, then trying to chamber the dummy round in the Savage. As expected, there wasn’t enough clearance at the front end of the chamber.

While waiting for the handloading stuff, I mounted a 3-9x 40mm Trijicon AccuPoint scope on the Savage to range-test the factory ammunition, which would also provide some empty cases to load. Over the years, I’ve taken quite a few big-game animals with AccuPoints, including one of my biggest mule deer, some African plains game, and an Alaskan grizzly, and I really like their battery-free illuminated aiming points, made of a combination of tritium and fiber optics. The reticle in this particular 3-9x is the TR20 Amber Triangle Post, which works very well for whitetail hunting, the primary purpose of the .350 Legend.

Official SAAMI .350 Legend test- barrels are 16 inches long, no doubt due to AR-15s. The advertised velocity for the Winchester 145-grain load is 2,350 fps, but from the “long” 18-inch barrel of the Savage, it averaged 2,427 fps over a light-screen chronograph at 15 feet, the standard SAAMI distance. The Hornady 170-grain load is listed at 2,200 fps, but also ran faster, averaging 2,323 fps. Three-shot groups at 100 yards ranged around 1 to 1½ inches, more than sufficient at typical Midwestern whitetail ranges.

After the other stuff arrived, I set up the Lee bullet sizer in my stoutest press, a Redding Big Boss, then lightly applied Redding Imperial Sizing Die Wax to the shanks of a few 180-grain Speer Hot-Cors. They squeezed through the die with less effort than full-length sizing .223 Remington cases.

However, they did not measure .355 inch, instead averaging .3564, as measured with my pair of Starrett micrometers, an old vernier-scale model and a more recent digital. I thought this might be due to spring-back of the jacketed bullets, so I tried sizing a 158-grain .357-diameter cast bullet, which measured .3561.

The .356 diameter of the Lee sizer might be due to cast-bullet shooters preferring bullets slightly larger than bore diameter, but the resized Speers were still small enough to allow loaded rounds to chamber easily, my primary desire. (Anybody who’s measured different brands of jacketed bullets for a specific caliber also knows they can vary .001 – or even more – in diameter.)

Both brands of brass weighed almost exactly the same, and produced essentially the same velocity when I tried one bullet/powder combination in both brands. Since the .350 Legend “headspaces” on the mouth of the case like rimless pistol cartridges, I trimmed them to the SAAMI 1.710-inch length after every firing.

While .350 loading data is scarce, there proved to be enough to indicate that Hodgdon Lil’Gun is the most popular choice, though slightly slower-burning Alliant Power Pro 300-MP also works well. While some sources, including Hodgdon, list higher maximum charges than those in the load table, I stopped adding powder when muzzle velocities approximated the two factory loads.

Like the .223 Remington, the .350 Legend uses small rifle primers. I used CCI 450 Magnums, partly because they have slightly thicker cups than “standard” small rifle primers, and partly due to very good results in other rifle cartridges, ranging up to the 6.5 Creedmoor with Lapua small primer cases.

This is considerably higher than the 40,000 psi MAP for the .357 Maximum handgun cartridge. Yet, while surfing the internet for information on the .350 Legend, I came across a handloading forum where one guy insisted the .350 Legend was “nothing more than a rimless .357 Maximum.” This is obviously incorrect, due to both pressure and powder capacity: The .350 Legend’s case is more than .1 inch longer than the .357 Maximum’s, and the Maximum’s SAAMI MAP is only 40,000 psi. (This is only one of many examples of nitwits posting on internet handloading forums.)

The resized Speer 180-grain shot almost as accurately as the Hornady 170-grain Spire Points. This success led me to experiment with the Hornady 200-grain FTX bullet, which has worked well for me in the .358 Winchester. Hornady’s most recent Handbook of Cartridge Reloading 11th Edition lists this FTX as one of three 200-grain bullets suitable for handloading the .35 Remington, indicating the FTX should expand well in the .350 Legend. (This is not surprising, since the 200-grain FTX was primarily designed for use in tube-magazine, lever-action .35 Remingtons.)

While no published .350 data listed bullets weighing over 180 grains, I felt confident in starting with powder charges a couple grains lower than those listed for 180s. The charges in the table are just slightly compressed by the relatively long 200-grain FTX, and none showed a hint of excess pressure.

It should also be noted that, like most other Hornady cup-and-core big-game bullets, the FTXs feature the Interlock ring on the inside of the jacket, which helps hold the core in place during bullet expansion. I wouldn’t be surprised if the .350 with 200-grain FTXs worked pretty well on timber elk, partly due to once knowing an older Montana elk hunter who did fine with his .35 Remington and 200-grain Core-Lokt factory ammunition.

After working up the rifle bullet loads, I ran their numbers through the Berger Bullets online ballistic calculator, at 35 degrees Fahrenheit and 1,500 feet above sea level. While the .350 Legend is definitely NOT a long-range round, the bullets listed – including the flatnose Speer, essentially a flat-tipped spitzer – fly pretty well at typical whitetail ranges. When sighted-in 2 inches high at 100 yards, the calculator showed them landing 3-4 inches below point of aim at 200 yards, even the 200-grain FTX, because it has a listed BC of .300. This might not seem like much to a long-range hunter, but it definitely works for the intended purposes of the .350.

The downside of the pistol-bullet loads is they would not feed from the Savage’s three-round detachable magazine, though all the rifle bullets did, even the flatnose Speer. I also have several brands of AR-15 magazines on hand, and tried pushing the pistol-bullet loads from them manually, which didn’t work. All the other loads easily slipped out.

After doing all the shooting, I started to suspect Winchester might have gone to the 9mm/.355-inch bullet diameter to get just a little more taper in the cases for surer magazine feeding. While .002 inch more taper isn’t much, in a 1.7 inch case, it might make a difference, though this is obviously still a guess about Winchester’s somewhat mysterious cartridge. What is not a mystery is how well it works for its intended purpose, since the .35 Remington has been doing basically the same thing for well over a century – even without spitzer bullets.

.jpg)