.38 WCF

Really Old, but Still Capable

feature By: Terry Wieland | November, 22

When a cartridge approaches 150 years of age, it’s only reasonable to expect some problems. The .38-40 (originally known as the .38 WCF) was introduced around 1880, in the Winchester Model 1873, and soon after was chambered in the Colt Single Action Army. Since then, it has been chambered in a wide variety of both rifles and handguns, most of them long obsolete and many readers probably never heard of, much less seen them.

The guns may now be ghosts, but they are ghosts that continue to haunt the .38-40, limiting its ballistic performance in factory ammunition as well as the allowable handloads I can find in published load data.

The problem is that when the industry establishes standard maximums, it must always bear in mind that modern ammunition could find its way into old rifles that by design, metallurgy, or a century’s worth of neglect, will no longer take the pressure.

That, ladies and gentlemen, is only one of at least a dozen problems that continue to plague admirers of the .38-40 in this year of our Lord, 2022.

Way back in 1975, when the .38-40 was a spry 96 years old, Ken Waters wrote a “Pet Loads” article in these pages in which he went into detail about the problems that then existed. Some of these have faded, but they’ve been replaced by new ones. Waters’ article was reprinted in Wolfe Publishing’s massive compendium of his excellent work, Pet Loads, and I strongly recommend it if you can’t dig up your copy of the original Handloader No. 53 (January - February 1975).

The .38-40, aside from everything else, has been widely misunderstood throughout its lifetime – usually compared to its stablemate, the .44-40, and found wanting. In fact, both the .38-40 and the .44-40 are misnamed, and ballistically there is so little to choose between them that it’s pointless to try. The .38-40 is not a .38, it’s a .40, while the .44-40 is actually a .43; the former shoots a 180-grain bullet, the latter usually a 200-grain bullet, and the velocity difference is about 30 feet per second (fps). Hit a deer in the same place with either and I can promise the deer will never know the difference.

Both cartridges, like many of that era, were intended to be dual-purpose, chambered in both your rifle and revolver, and simplifying the ammunition problems as hunters ventured into the great unknown. Obviously, a round fired in the 26-inch barrel of a rifle is going to have greater velocity than one fired from a 71⁄2-inch revolver. However, factory ammunition must be safe to fire in either one.

Aside from the Winchester ’73 and black-powder Colt SAA’s, the round was chambered in a few single-shot rifles, like the Stevens on its weaker No. 44 action. Later, it was chambered in the excellent, and much stronger, Winchester Model 92. My test rifle is a 92. Waters divided his data into that suitable for his list of ‘weak’ and those suitable for the ‘strong.’ I’m not going to do that, since I don’t have adequate acquaintance with all the rifles in question. Instead, we’ll stick to Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) limits as shown in current load data, and trust readers to make their own judgments as to the strength of their firearms.

Let’s deal with the thorny question of data right off the bat. The original factory load was a 180-grain cast bullet ahead of 40 grains of FFg, at a velocity of 1,330 fps for 705 foot-pounds of energy at the muzzle. There was the usual bumpy transition to smokeless powder, and ammunition makers went to great lengths to offer hunting loads with expanding bullets at higher velocities, and handloaders attempted to do likewise on their own.

The earliest data I can find is in the Ideal handbooks (later Lyman) and some of their recommendations are hairy, to say the least. Ken Waters tried some of them, notably some really stiff loads with Alliant 2400 and IMR-4227 and experienced case separations. He recommended flatly that this data never be used, regardless of what rifle a shooter has.

Suggested maximum loads have been toned down considerably in recent years, but many will be thrown back on old data simply because there is no new data. Handloaders are unlikely to find formula using new hotshot powders because powder manufacturers are not likely to do the necessary testing for a cartridge of such limited demand. Hodgdon is a partial exception, offering data for such powders as Clays, Universal, Titegroup and Trail Boss.

At any rate, approach any data from before 1975 with extreme caution. Early data also included powders that are no longer with us, such as SR-4759. This is another limiting factor.

There used to be a general problem with brass, since handloaders might come across both ancient folded- head and balloon-head brass, both of which should be avoided. As well, some manufacturers fitted .38-40 brass with small primer pockets, which is more of an annoyance than anything. However, if you try to load modern, thicker brass with the original 40 grains of FFg, you’ll find it doesn’t fit. My Winchester-Western cases accept only 39 grains, and that is to the mouth of the case, leaving no room for a bullet. To the base of a typical bullet, it is 26 grains, which is a far cry from 40.

Black-powder devotees already know this, but it bears saying again: There are grains measured by weight, and grains measured by bulk, and although they can be very close, the relationship is not exact. For example, 40 grains of GOEX FFg (by weight) is about 38 grains bulk – in my tools at, least. Switch to a finer-grained powder (another confusing use of grains) and the difference can be much greater. Twenty grains bulk of Swiss FFFFg is about 23 grains by weight.

There were vagaries with chamber dimensions from manufacturer to manufacturer and .38-40s are notorious for having imaginative chambers. My rifle is no exception: The brass that goes in looks quite different from the brass that comes out, with the shoulder much more pronounced. Redding dies do not resize it to original dimensions, however, so maybe the chamber of my 92 is more or less standard.

Now for bullets. The traditional bullet is cast, with Lyman 40143 producing a flatnosed bullet weighing about 172 grains, depending on the alloy. These are supposed to be sized to .401 to .403 inches, sometimes depending on your bore diameter. There seem to be lots of moulds floating about, if you want to cast your own. Twenty years ago, when I began loading the .38-40, there was little around in the way of commercial bullets in the .401 range; today there are many more, both cast and jacketed, but most are intended for the 10mm semiauto and lack one critical feature: a cannelure or crimping groove.

Most authorities insist the .38-40 must be crimped solidly, but this is mainly because, in the lengthy tubular magazine of the 92, which holds about 15 rounds, during the course of a shooting session, they can get pounded, seating bullets deeper into their cases and potentially affecting feeding. There is the opposite concern with revolvers, where bullets can creep forward under recoil and prevent the cylinder turning. Obviously, neither is a problem with a single shot.

Years ago, I bought a cannelure tool to impress a cannelure on the 180-grain swaged bullets I obtained, and that worked well enough, though it was tedious. Related to this, the cannelure has to be in the right place; cartridges that are too long or too short do not work well in the Winchester and Marlin rifles with tubular magazines. The cannelure on a bullet for the .38-40 can’t be thrown on just anywhere: It has to be exact.

This requirement also places limitations on bullet weight. Practically speaking, the .38-40 is at its best with bullets ranging between 160 and 200 grains, with 180 – the original – offering the fewest problems. While we’re speaking of tubular magazines, they demand bullets with either round or flatnoses. No spitzers, to ensure no unscheduled firing of the primer in front under recoil.

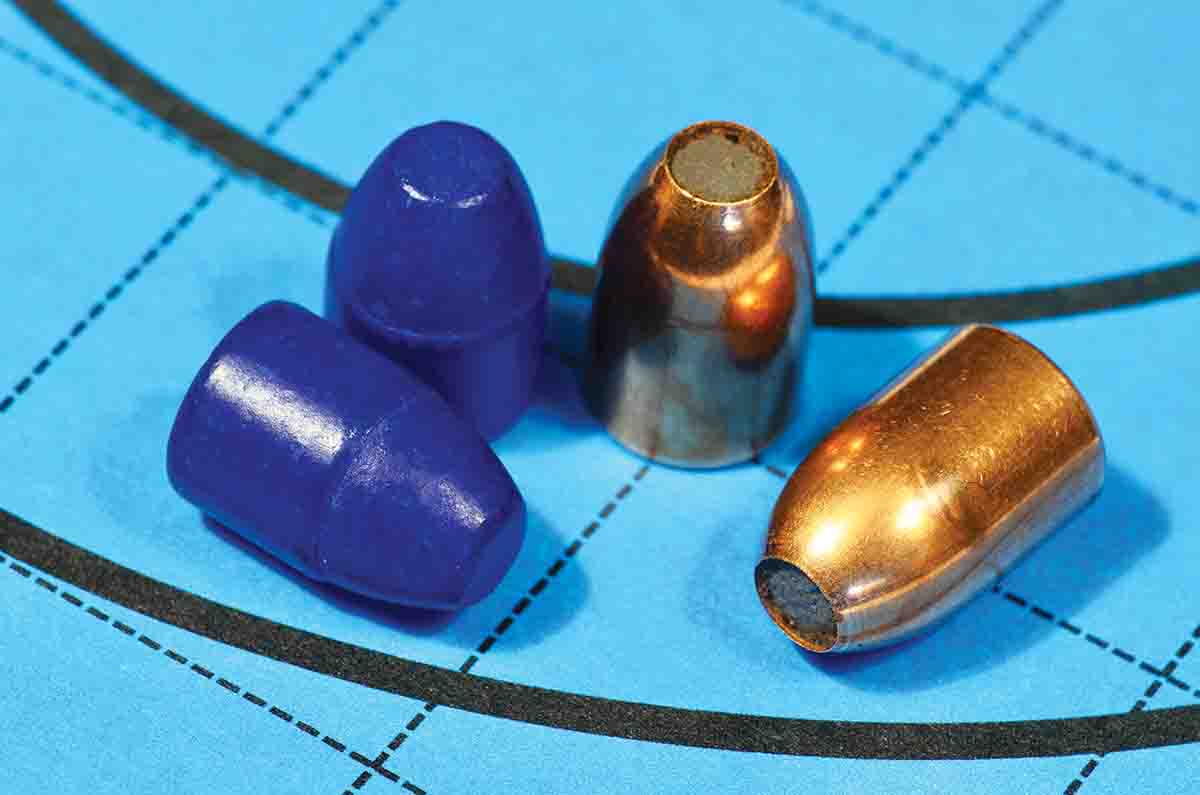

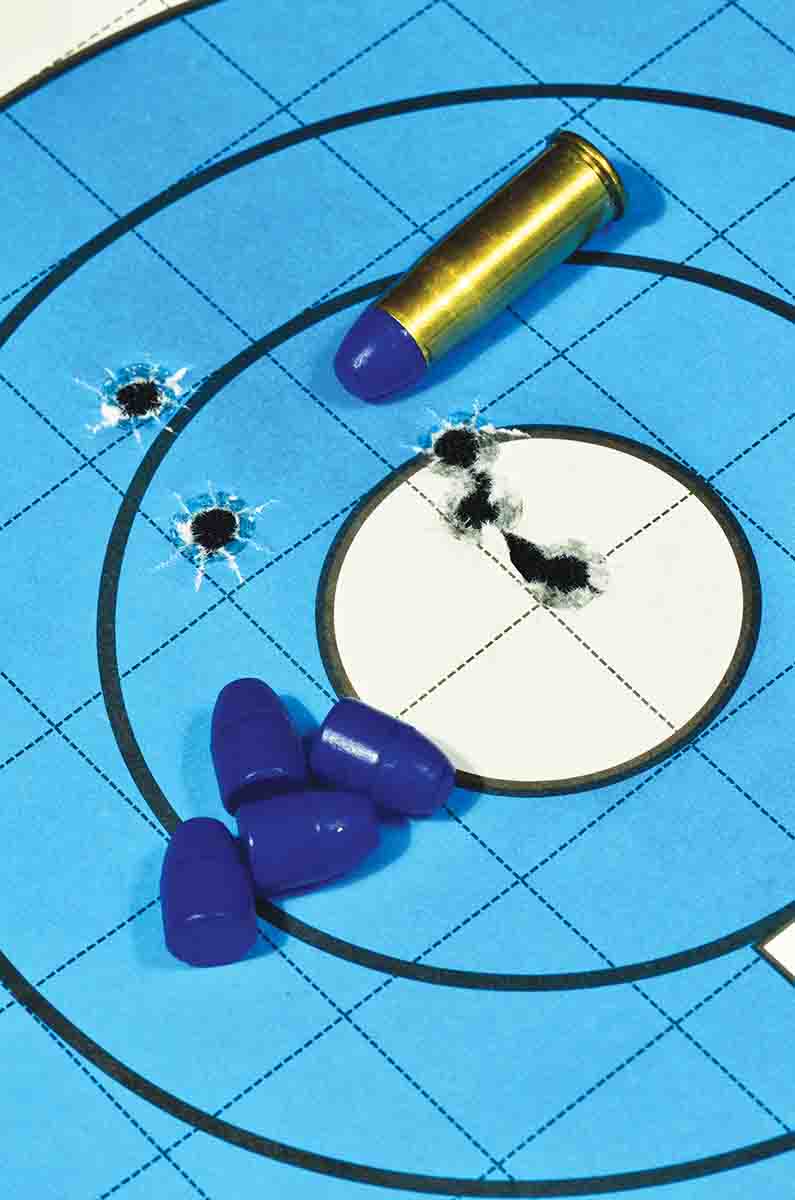

The two bullets I tested for this article came my way largely by chance. The first is a 165-grain from The Blue Bullet Company. It’s a semi-wadcutter, mainly intended for the 10mm. It is polymer coated, and measures exactly .400 inch, but I wanted to see if it could work in the .38-40. It has no cannelure. The company offers a similar bullet in 180 grains, but it was out of stock. For that matter, I was only able to obtain 50 of the 165s, which limited testing rather severely.

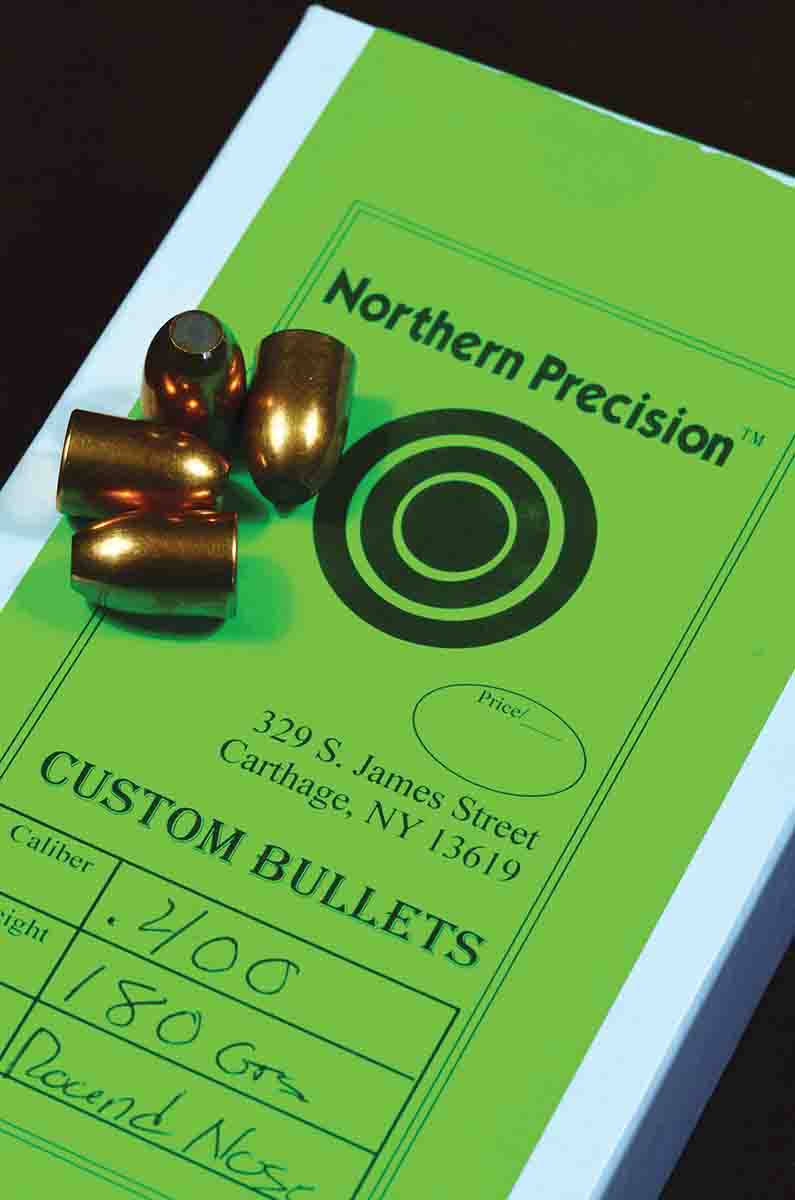

The second is a jacketed roundnose from Bill Noody’s Northern Precision Bullets in upstate New York. It weighs 180 grains, and is also without a cannelure. It measures exactly .400 as well. Since Bill does put cannelures on some of his bullets, it should be possible to get these cannelured if you so desire. Given their performance (see accompanying table) it would be well worthwhile.

Neither variety of bullet was held very snugly in the case, so after seating them to the correct depth, I ran the cartridge back into the sizing die (with the decapping rod removed, of course) and it tightened the mouth of the case just enough to hold the bullet in place. Of course, this is a stop-gap measure, and I was not trying to develop loads just for the 92. Rather than take a chance, I fed the cartridges into the chamber one at a time.

Suitable powders for the .38-40 range from the oldest (and still a favorite) Unique (Alliant), to the newest, IMR Trail Boss from Hodgdon. Handloaders can still find data for Alliant’s Herco, 2400, Bullseye, and Red Dot as well as SR-4759 (if you have some hidden away). There is also data for 4227; older manuals will not differentiate between IMR-4227 and Hodgdon, but they mean IMR, since Hodgdon’s version did not yet exist.

For the Blue Bullet, I stuck to guidelines I would use for cast bullets; that is, I did not want velocity to exceed 1,400 fps. With the jacketed bullet, I was looking for velocities up to, possibly, 1,750 fps.

I also wanted to try some of Ken Waters’ loads from 1975, for comparison, as well as to see what Unique and 2400 could still do.

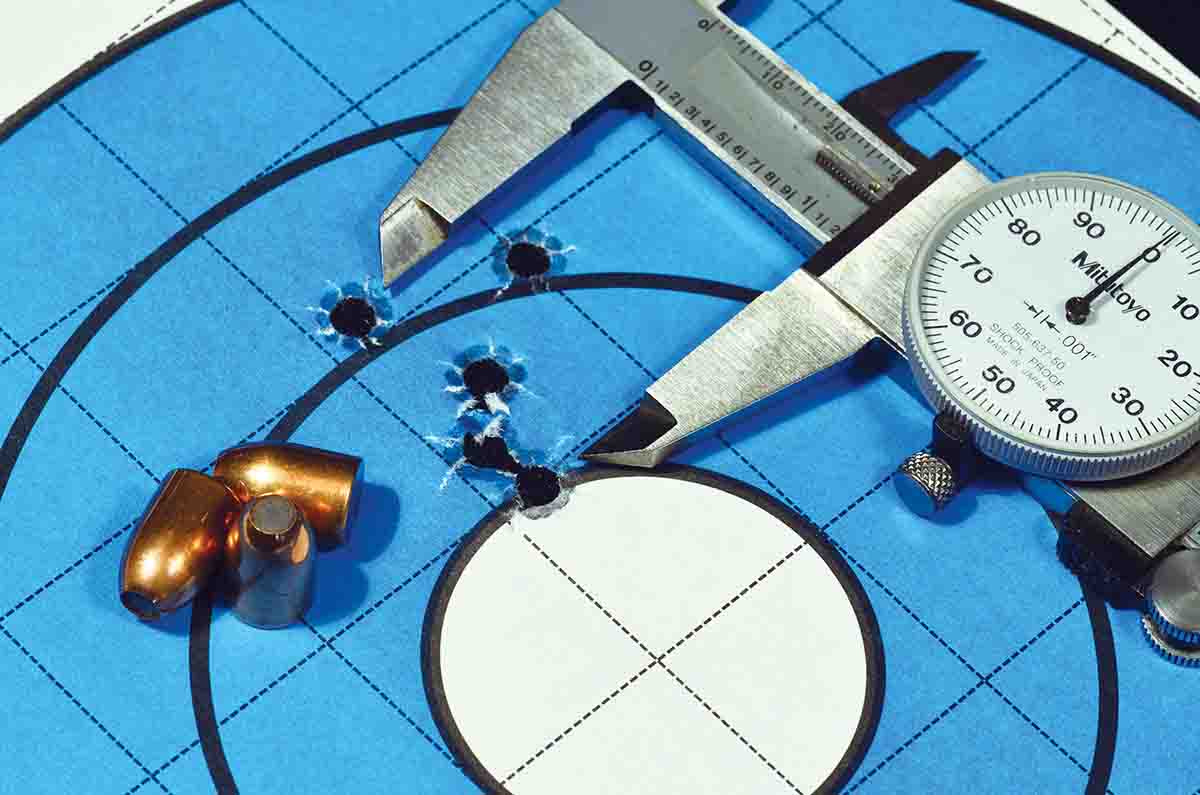

The main conclusion I came to is that Unique and 2400 are still every bit as good in this cartridge as they ever were. With the Northern Precision jacketed bullet, 2400 delivered excellent hunting velocity, with Unique not too far behind, and accuracy was good in both.

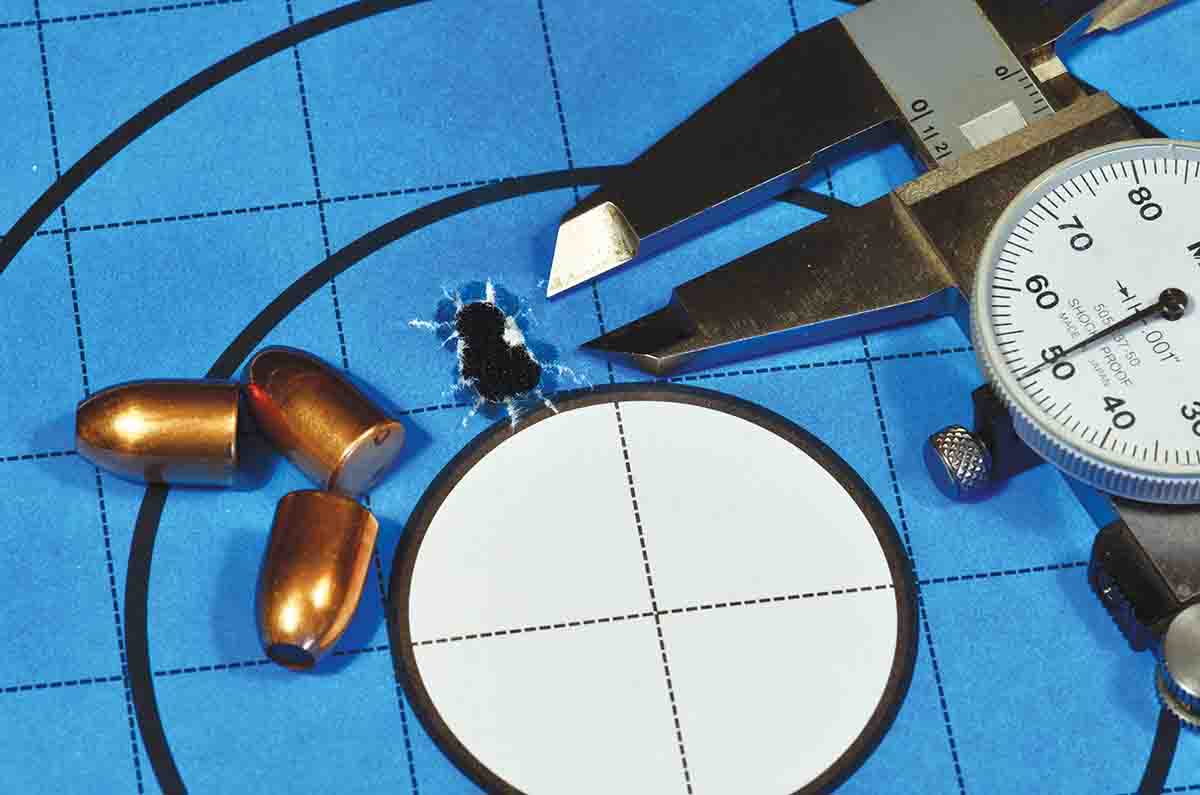

The Northern Precision bullet ahead of Hodgdon’s Universal Clays delivered a group that was nothing short of astonishing, but I’ve had groups like that before that have turned out to be flukes. Still, it’s not every day I see performance like that with an iron-sighted .38-40.

As expected, IMR’s Trail Boss proved to be an excellent choice for Cowboy Action with the 165-grain Blue Bullet. Otherwise, all the powders tested, old and newer, were good with that bullet. There simply wasn’t much to choose among them.

All in all, today’s .38-40 shooter has more to choose from than even 20 years ago. Put a cannelure on the Northern Precision 180-grain jacketed bullet, load it ahead of a charge of Alliant’s 2400, and the iron-sighted 92 becomes as good a brush rifle as one can find. Not bad for a rifle-cartridge combination that is 130 years old.

.jpg)