My tenure with this column is now something over 30 years, so regular readers will wonder why I haven’t already covered a popular round like the .30-30 Winchester? It was listed before my time, but the column was then shorter in length so information had to be left out. This will be included now, plus more that has been learned about this fascinating old round. One solid fact is that the .30-30 is far from dead or obsolete. It is perhaps more useful today than during its first 20 years of existence!

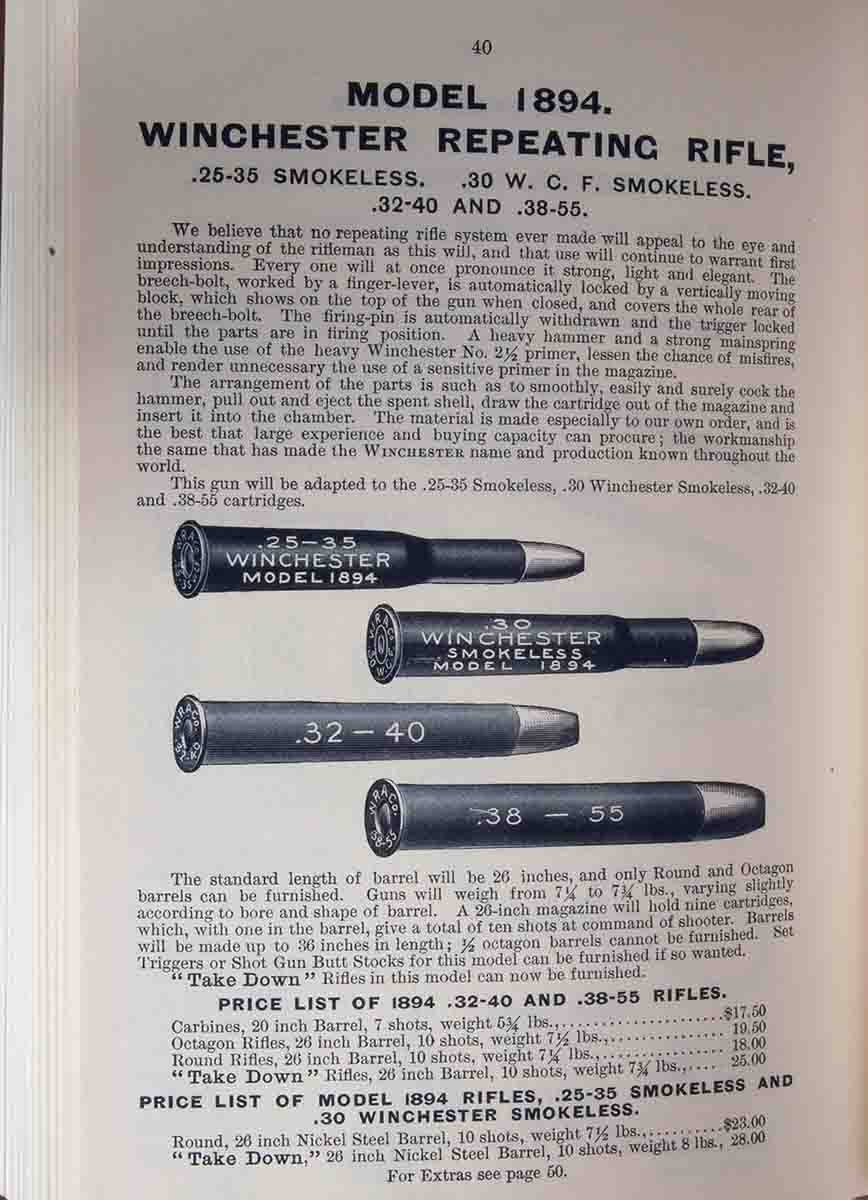

The (1) black powder .32-40 and (2) .38-55 were the first rounds chambered in the Model 1894 rifle, followed by the (3) .25-35 Smokeless and (4) .30 WCF Smokeless some 10 months later.

The road to the .30-30 runs through Winchester’s levergun designs of the last half of the nineteenth-century. The earliest rifles (Model 1866 and Model 1873) used what is often called a toggle or toggle-lock mechanism to resist the rearward force on the breechblock when a cartridge was fired. Think of this as a Luger pistol action, but upside down and inside the receiver where it can’t be seen. Such a system is not very strong and subject to wear that causes headspace to increase. The guns were also heavy with rifles about 9 pounds and carbines about 7.5 pounds, but their black-powder cartridges only generated 400-750 foot-pounds of muzzle energy. That is less than most .44 Magnum handgun loads.

John Browning saved Winchester with what became known as the Model 1886. Firing big cartridges of up to .50 caliber, the rifle kicked, as the old-timers phrased it, “Like a Missouri mule!” This despite a gun weight of 9 to 10 pounds.

Left to right: an early .25-35 Smokeless with 117-grain full patch bullet, an WRA CO .30 WCF Smokeless with its first bullet and a 160-grain full patch roundnose. A flatpoint bullet was not seen until after World War II.

Smokeless powder was still mysterious, so in order to get a lighter, handier arm, Winchester scaled down the Model 1866 to produce the lovely Model 1892. Unfortunately, the only cartridges it could chamber were the same three used in the earlier Model 1873. All black powder of course. One good thing was a decrease in gun weight. Rifles weighed about 7 pounds and carbines were around 6 pounds.

Despite the low-powered rounds of the Model 1892, the gun was commonly used on whitetail deer and black bear instead of larger, harder- kicking cartridges. Many animals were taken, but a lot had to have escaped due to insufficient bullet energy. As was said earlier, these small rounds generated less energy than most .44 Magnum handgun loads today and tales of deer running off into the forest after being shot with it are not uncommon. This was one of the reasons for the creation of the .454 Casull, .480 Ruger, etc.

With the introduction of the Winchester Model 1892, the company had nearly the entire field of black-powder hunting cartridges covered by it and the Model 1886. Those that were simply too huge to fit in any repeater were available in the Winchester Single Shot.

By 1890, Winchester wanted to replace the Model 1873 because the action was considered weak, the gun heavy and its .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40 cartridges no more than pistol rounds.

While it would appear the situation could not have been better for Winchester, there was one overwhelming concern growing larger every day. That was the production of a smokeless powder by France in 1885. Fielding of a new repeating rifle to fire a smokeless cartridge called the 8mm Lebel. France sealed the deal in 1888. Smokeless powder was available and everyone wanted their cartridges loaded with it.

By the early 1890s, powder companies had been formed and were selling smokeless compounds to anyone who would buy them. Winchester began experimenting with smokeless powders at this time, but the many varieties available and poor uniformity from batch-to-batch made the work go slowly. Nevertheless, the company promised its customers it would add smokeless loads as fast as they could be developed.

Winchester’s lovely Model 1892 was light and strong, but was too small for anything but the Model 1873’s .32-20, .38-40 and .44-40 rounds.

At first, all development went toward simply replacing black powder with smokeless. Bullet weights and muzzle velocities were not changed. Then, at the same time, the U.S. Army Ordnance Office wanted to adopt a small-caliber smokeless military round. No doubt the new French, German and British cartridges were the reason. Springfield Armory began this work, and these records are now gone, but Winchester somehow got involved in drawing cases and making .30-caliber bullets. This seems to be the first mention of a .30-cailber bullet in a smokeless powder cartridge.

The result of this work was the adoption of the U.S. Army (.30-40 Krag) in June 1892. How much “development” went into this round is questionable as it is just a .303 British of 1888 with the case shortened .040 inch and the bullet is reduced .003 inch in diameter. There can be little doubt that Winchester’s work with the .30-caliber Springfield round, and its later adoption by the army, is the reason that caliber was later picked for one of Winchester’s first two smokeless powder cartridges.

Browning’s Model 1886 gave Winchester a big, powerful levergun that was heavy and fired big, hard-kicking cartridges like the .45-70 shown here.

Even though Winchester quickly offered loaded ammunition for the .30 U.S. and chambered the famous Single Shot Model for it, Winchester’s own cartridges would not be ready for a while. There was a good

reason for this. The companies experience with smokeless powders showed that its high-burning temperatures quickly eroded rifling. The U.S. Navy, however, had just begun using steel alloyed with nickel for warship construction because of its superior hardness and toughness over unalloyed plate. Winchester’s access to this steel was due to its work on the .236 Navy (6mm Lee-Navy) cartridge. It was found that an alloy containing 3.2 percent nickel, made a much more wear-resistant barrel steel, but was difficult to machine. Winchester’s William Mason solved that problem. The alloy was employed until 1909 when .25-30 carbon and .5 manganese were added, producing a steel used by Winchester for 35 years in barrels marked “NICKEL STEEL.”

A page from the August 1895 Winchester catalog showing the first mention of .25-35 Smokeless and .30 WCF Smokeless.

Next is the idea that Winchester needed a “smokeless powder action” for its new cartridges. John Browning designed what became the Model 1894 action especially for smokeless powder. All this seems to be just so much storytelling! By the 1890s, much progress had been made in the production of steels that were stronger than ever before. Hot forging gun parts made them better yet. The Model 1894 is smaller and thinner than the Model 1886. There was nothing to make it inherently stronger except the material it was made from. I believe Winchester wanted a lighter action (and thus lighter rifle) that would handle a new, smallbore smokeless cartridge capable of cleanly taking deer and black bear. It was as simple as that.

The November 1894 Winchester catalog announced the new Model 1894 rifle in only .32-40 and .38-55 (both black-powder rounds) with the lead sentence, “We believe that no repeating rifle system ever made will appeal to the eye and understanding of the rifleman as this will, and that use will continue to warrant first impressions.” That was no exaggeration! Rifles weighed 7.5 pounds and carbines were 5.75 pounds.

Nine months later, Winchester catalog No. 55 simply listed two new cartridges, .25-35 Smokeless and .30 WCF Smokeless, as being available in the Model 1894 rifle only, not the carbine. That was all! It’s almost as if the company didn’t want anyone to know. It also makes me wonder why authorities keep telling us that the .30 WCF (.30-30 Winchester) was the first commercial smokeless powder sporting cartridge available. I count two.

The Model 1899 Savage (top) was quickly chambered for .30 WCF Smokeless. An early Model 1894 carbine (bottom) has had most all parts replaced except the barreled receiver and lever. Still, it takes a deer from a tree stand every year.

Only one cartridge was listed in the catalog’s ammunition section for the new .30 caliber; a 160-grain roundnose bullet pushed by 30 grains of smokeless powder to 1,970 feet per second muzzle velocity and 1,400 foot-pounds of energy, from a 26-inch barrel. This was enough to make the bullet fly flatter to 300 yards than any other loaded by Winchester at the time, except the 135-grain from the .236 Navy. I will have more on this impressive pair, the Model 1894 and .30 WCF Smokeless cartridge, in my next “Cartridge Board” column.

.jpg)