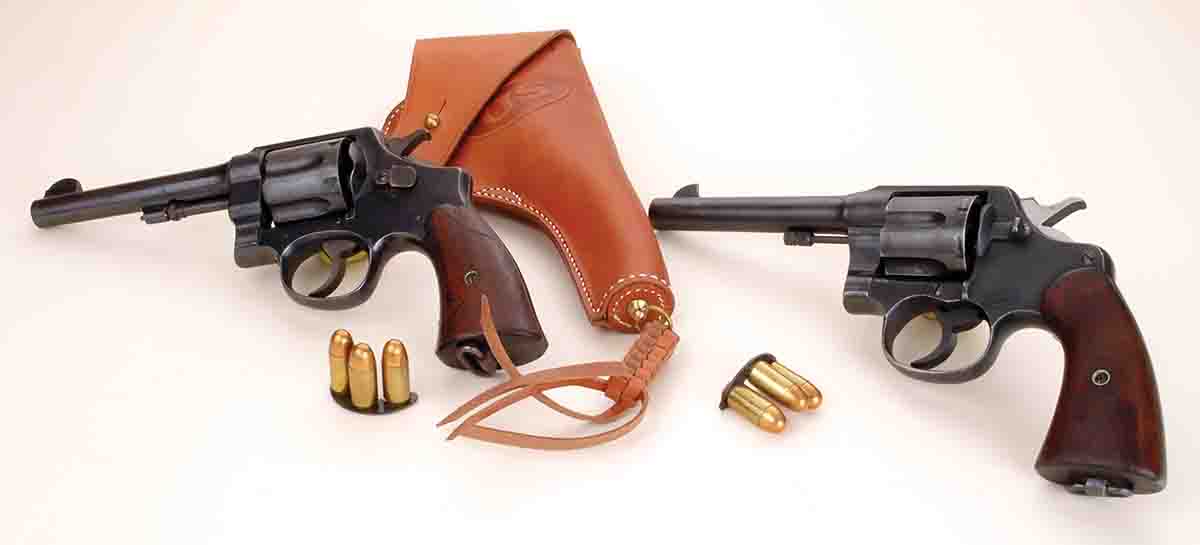

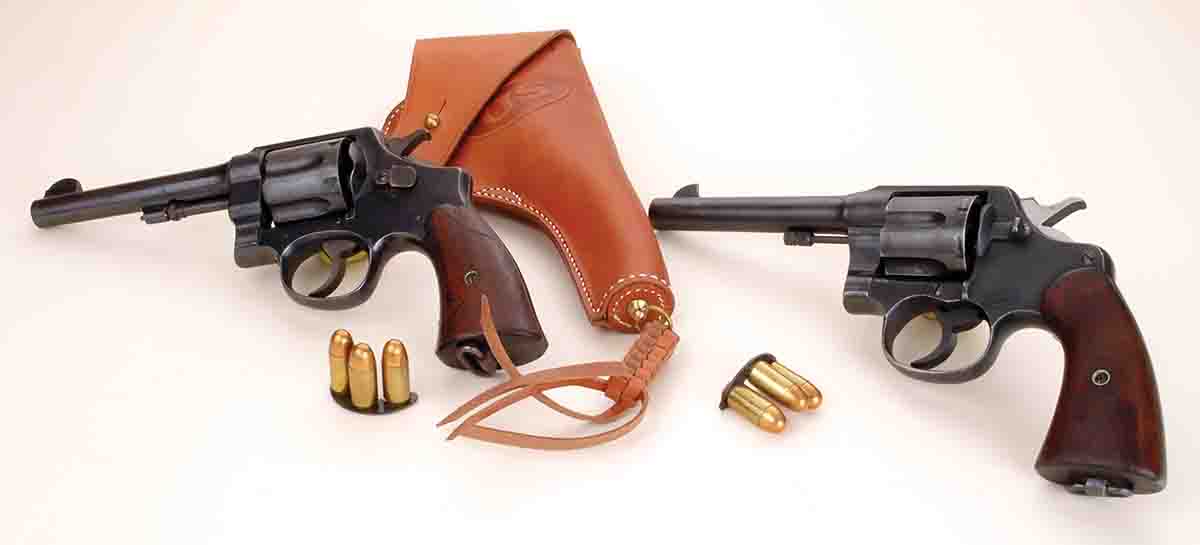

For World War I, the U.S. Government had both Colt and Smith & Wesson produce hundreds of thousands of the large-frame revolvers for .45 Auto using three-round, half-moon clips. A Smith & Wesson Model 1917 (left) and a Colt Model 1917 (right) are shown.

Some general or another once said something like, “No battle plan survives intact after the first shot is fired.” As conceived, my original idea for this article involved handloading .45 Auto Rim for U.S. Model 1917 revolvers made by both Smith & Wesson (S&W) and Colt. At first, shooting the S&W Model 1917, it developed a mechanical problem so it was dropped from test shooting. For decades, both types of Model 1917 revolvers sat on bottom shelves of used gun cases in stores across the nation. Now, they are now esteemed military collectibles and as such, they have gained phenomenally in value. For instance, my current S&W Model 1917 cost about 20 times what was paid for my first one in June 1968.

A Colt U.S. Model 1917 .45 Auto. Dies used were regular .45 Auto by Redding. The only change was the RCBS No. 8 shellholder seen atop the box. Notice the vintage Lyman box labeled “.45 Auto Rim.”

Instead of shooting jacketed bullet loads in 100-plus year-old revolvers, my opinion is that mild cast-bullet loads would be kinder to century-old steel. Therefore, for this project, a small array of lead-alloy bullets were loaded over charges of powders intending to deliver about 750 to 850 feet per second (fps) velocity from the 5½-inch barrels of the Model 1917.

A logical question here is: Why not use rimless .45 Auto cases in half- or full-moon clips? Indeed, Model 1917s were intended for rimless .45 Autos pressed into “half-moon” clips. As the photo shows, original military loads were issued pre-boxed in those clips. My reason for not using clips is that senior citizen hands and fingers are pained when inserting and removing .45 Auto cases from the clips a single round at a time.

The government inspector marking is found on the frame just in front of the hammer and the “Rampant Colt” is behind the cylinder release button.

However, before proceeding, let’s do the obligatory historical background of Model 1917 revolvers and the .45 Auto Rim. Model 1917 Colt and Smith & Wesson revolvers were a stopgap measure in the World War I emergency. As usual, this nation entered a war unprepared. Simply stated, there were not enough Model 1911 .45 Auto pistols available despite that at the height of wartime production, the Colt factory was producing about 2,000 Model 1911s per day! The government prevailed on the two above mentioned revolver manufacturers to develop a method for their respective large-frame sixguns to use rimless .45 Auto ammunition. It has been reported that someone at the S&W facility came up with the idea for spring steel, three round, half-moon clips to secure .45 Auto cartridges in chambers and give revolver extractors a surface to push against.

It was a great war-emergency idea. Between 1917 and 1919 collectively, the two manufacturers produced more than 300,000 .45 Auto revolvers. Not only did they serve in Europe during the war, but some were even issued to U.S. Post Offices during the inter-war years. Then, at the beginning of World War II, many thousand Model 1917s were withdrawn from stocks for reissue. (My own uncle related to me that he carried one in 1944 on the island of Guam as a member of the USMC 3rd Division. He had long ago forgotten if his was a Smith & Wesson or Colt.) Here is an interesting fact. World War I manufacturers shipped their Model 1917s to the U.S. Government with blued finish. However, if pulled from stocks for World War II and needing refurbishing, they were given a Parkerized finish. My S&W Model 1917 is still blued, but my Colt Model 1917 is Parkerized.

The bottom of both the S&W and Colt Model 1917 grip frames were stamped.

The Model 1917 saga didn’t end with cancelled government contracts in 1919. Both S&W and Colt management realized the idea of revolvers firing .45 Auto was a good thing. Smith & Wesson continued selling Model 1917s to civilians until about 1949 but then reintroduced the same basic revolver as the Model 1950 Army (Later Model 22) until 1966. Colt kept .45 Auto as a caliber option with its New Service until 1944 when that version of revolver was discontinued altogether. Early in this century, S&W reintroduced Model 22s in several versions. Smith & Wesson also offered target-sighted .45 Auto revolvers as Models 25 and 26. However, it must be stressed that only Model 1917 revolvers marked U.S. on grip frame bottoms were made in the original 1917-1919 production period.

Colt and S&W Model 1917s are the same, but different. Both are large frame, swing cylinder, six-shot, double-action revolvers with 5½-inch barrels, smooth walnut grips and lanyard rings. Sights for both are fixed blade fronts with grooves down frame top-straps for rear sights. They are in no way readily adjustable. Their differences are that except for the lanyard rings, no two parts of either company’s Model 1917s are interchangeable. For instance, S&W cylinders rotate counterclockwise and Colt’s rotate clockwise. S&W stuck with their usual high-polish blue finish but Colt put a duller blue on its version.

For this project, Mike used these four lead-alloy bullets: (1) Oregon Trail 227-grain roundnose, (2) RCBS 40-180-CM 230-grain roundnose-flatpoint, (3) AA Limited 231-grain roundnose-flatpoint and (4) Redding/SAECO No. 453 234-grain wadcutter with a (5) Remington 230-grain lead-roundnose for comparison.

As mentioned above, the idea of revolvers firing .45 Auto clicked with the post-World War I gun-buying public. There was just one complaint; getting .45 Auto cartridges into the clips and out again. Doing so without specialized tools is time consuming and hard on fingers. That annoying problem was the basis for a brand new cartridge named .45 Auto Rim introduced by Peters Cartridge Company in 1920. This new round was simply the .45 Auto case redesigned to have a rather thick rim. For example I just picked up a stray .357 Magnum case off my bench. Its rim thickness is .051 inch. A .45 Auto Rim there has a .091 inch thick rim. Both cases were headstamped R-P for Remington-Peters.

CARTRIDGES OF THE WORLD 9th EDITION lists .055 inch and .085 inch for rim thicknesses of the two rounds. Go figure.

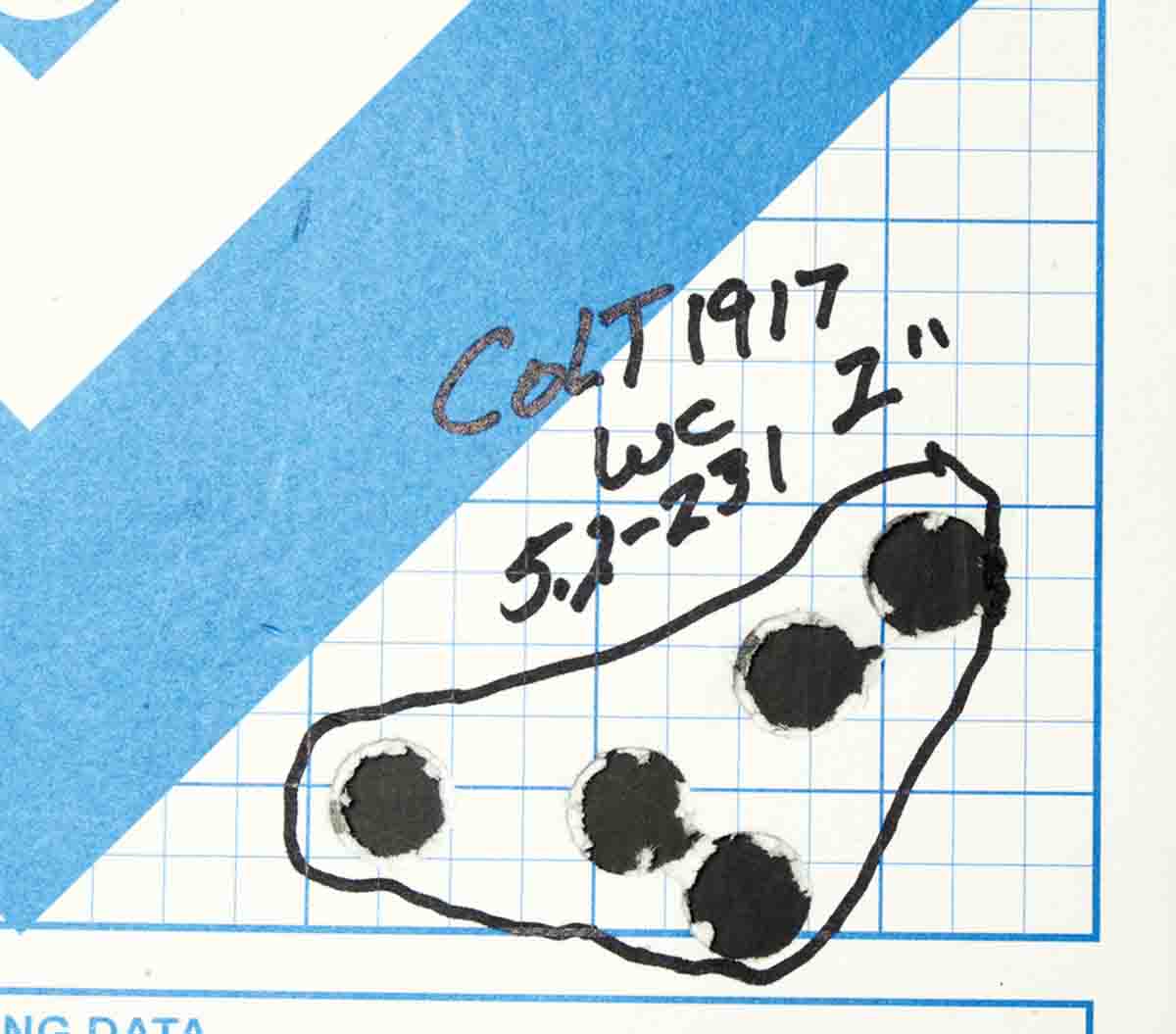

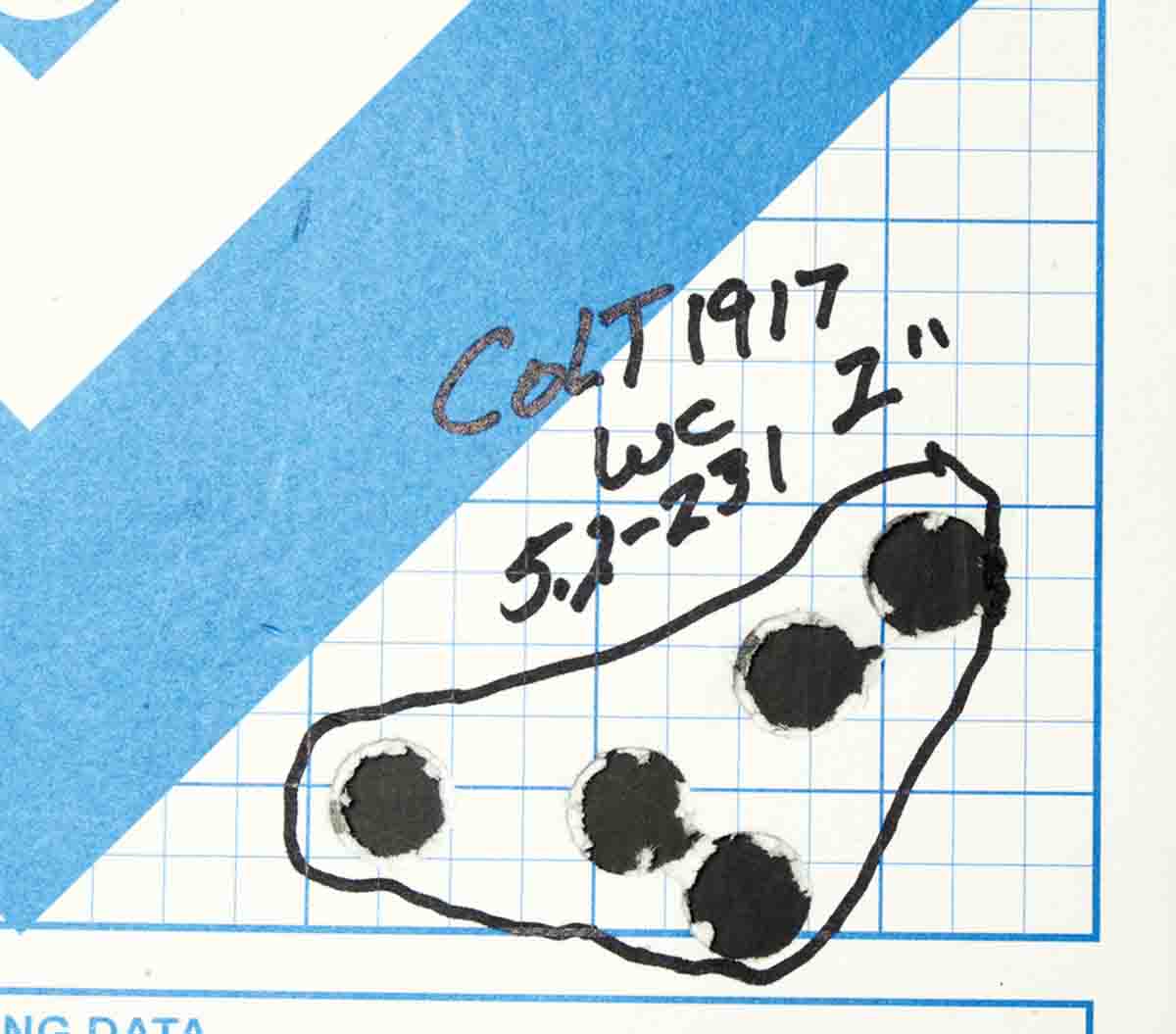

This is the best group fired from 25 yards with the Colt Model 1917. Note the flyer, which seemed common when shooting these groups.

According to the book

U.S. CARTRIDGES AND THEIR HANDGUNS by Charles R. Suydam, besides Peters, .45 Auto Rim factory loads have also been produced by U.S. Cartridge Company, Remington-Union Metallic Cartridge Company and Winchester Repeating Arms. Obviously, Remington and Peters united along the way. When my .45 Auto Rim shooting career started in 1968, only R-P factory loads were to be found and even those have also been discontinued for some years. My last box of factory Remington-Peters .45 Auto Rim contains a mere four rounds. Some Black Hills and Cor-Bon factory loads have been produced in this century, but my feeling is those should be saved for the newer .45 Auto Rim revolvers.

The second best group fired at 25 yards with the Colt Model 1917.

Early .45 Auto Rim factory loads used the same 230-grain full metal jacket bullets as .45 Auto but along the way, 230-grain lead roundnose bullets were introduced. My old chronograph notes show velocity for them was around 750 fps. In the past, I’ve read that rifling for Colt and S&W Model 1917s was shallower than for its other .45-caliber revolvers. However, I have a Colt factory specification sheet dated 1922, that lists all .45-caliber barrel groove diameters as .451 inch minimum and .452 inch maximum. It also specifies that all rifling groove depth for calibers from .22 to .45 was .0035 inch.

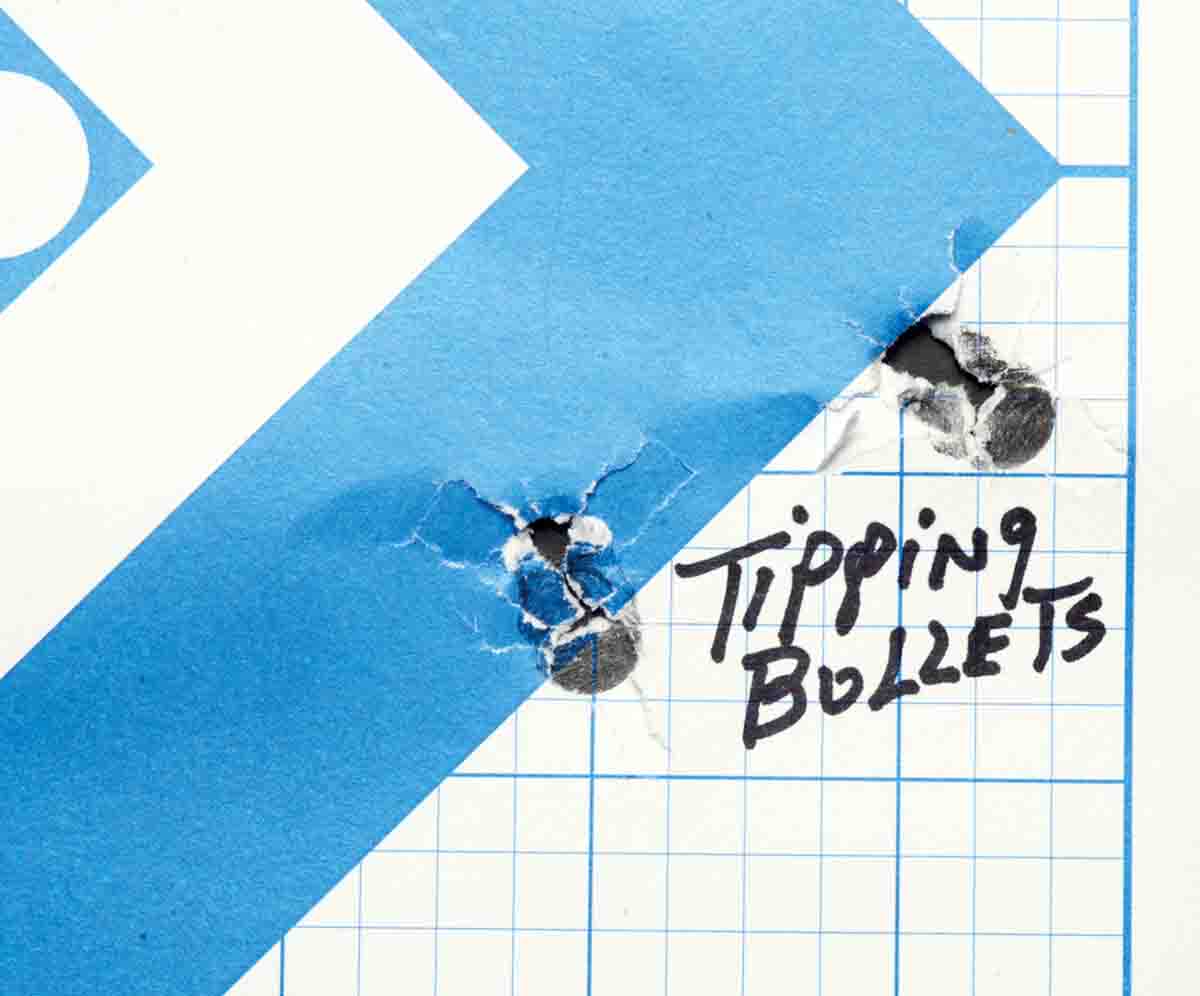

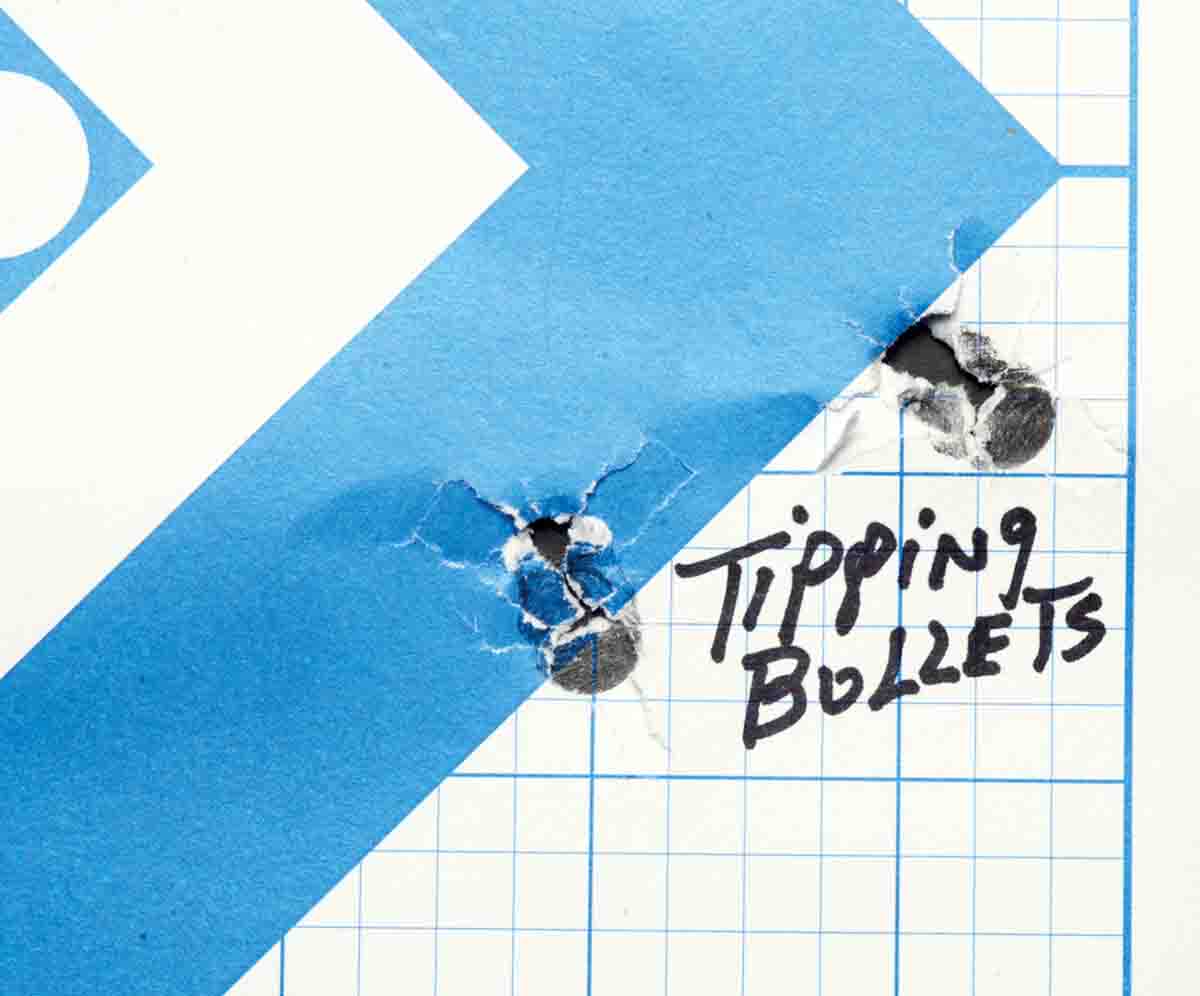

For reason(s) unknown, the Oregon Trail 227- grain roundnose bullets often tipped like this.

A conundrum I’ve found is as follows. Colt and S&W revolvers were designed for .45 Auto and I’ve never read any caveat saying to beware of using .45 Auto factory loads in revolvers so chambered. However, the

Lyman 50th Edition Reloading Handbook lists loads for its cast bullet 452374 (225 grains) giving slightly more than 17,000 cup pressures. However, the same manual lists .45 Auto Rim maximum pressures as slightly less than 14,000 cup for the same bullet. Comparing maximum charges for just one very popular propellant – Unique – showed 7.3 grains for .45 Auto, but only 6.6 grains for .45 Auto Rim. Again, with both rounds loaded with cast bullet 452374. I’m not disputing Lyman’s manual. In fact, it is my most referenced reloading manual. This is just being mentioned as something of which handloaders should be aware.

In times long past, reloading tool companies actually sold die sets marked specifically for .45 Auto Rim. However, any set of .45 Auto dies will suffice when used with the proper shellholder. In college, in 1968, I could not afford a .45 Auto Rim shellholder and my much younger fingers were more capable of loading/unloading half-moon clips. This is also when I learned of a problem when handloading for 1917 revolvers. The only .45 bullet mould owned at that time was Lyman’s 452374, a 225-grain roundnose meant primarily for .45 Auto. It has no crimp groove. My .45 Auto dies only roll crimped. The first time those handloads were fired in the S&W 1917, the third or fourth round’s bullet protruded from the chamber’s front! No matter how hard I tried to roll crimp on those smooth-side .45 Auto bullets, they always moved forward in cases during recoil.

Military ammunition for U.S. Model 1917 .45 Auto revolvers was issued prepackaged in the half-moon clips.

Now, fast forward many years when a Colt Model 1917 came my way. By this time, there was a .45 Auto taper crimp die on my reloading bench along with .45 Auto Rim brass and shellholder. I thought, “I’ll show those smooth-side bullets from Lyman mould 452374 who’s boss.” Again, bullets always moved forward during recoil. Next tried was a Lee Factory Crimp die. Same results, so with those experiences behind me I’ve only loaded .45 Auto Rim with bullets that can be solidly crimped.

That brings us to the bullets used for this project. Two were commercially cast and two were home cast. The latter came from Redding/SAECO mould 453 for a nominal 230-grain full wadcutter and RCBS mould 45-230CM for a nominal 230-grain roundnose-flatpoint. They were cast of 1:20 tin-to lead alloy, sized to .452 inch and lubed with DGL. They weighed 234 and 230 grains in the same order. For commercially cast bullets, Oregon Trail’s 230-grain roundnose was one pick. I know right here someone is thinking, “Mike, you’re contradicting yourself. That Oregon Trail bullet has no crimping groove.” True, but I thought its front driving band perfectly placed over which to roll crimp. Also in my storage shed, I found a bag of 230-grain roundnose-flatpoint bullets intended for .45 S&W “Schofield” produced by the now defunct AA Limited Company. The commercial bullets were both cast of very hard alloy, lubed with very hard blue lubricant and sized .452 inch.

Remington .45 Auto Rim factory ammunition was discontinued several decades ago. This is all Mike has left from his last box.

With those four bullets four powders were mated. Fast-burning powders are needed for a case with such small powder capacity. In the past, Red Dot has given excellent results in my now gone S&W Models 22, 25 and 26. However, it was ignored for this project because the most recent component shortage caught me with only a partial can. However, in plentiful supply were Bullseye, Titegroup, W-231 and Unique. All loads were stoutly roll crimped. Four bullets with four powders equaled a total of 16 combinations.

These were the four powders Mike used in this project.

Usually, averaging all groups and even individual averages per powder and bullet gives interesting information. Not this time: all four groups with Unique were wild as in 6 inches or more. The best groups came with Bullseye and W-231. In fact, the best group of all came with the AA Limited 230-grain “Schofield” bullet and W-231. Next best was the Redding SAECO 234-grain wadcutter, also with W-231. Most other Colt Model 1917 groups were in the 2- to 3-inch range, except with the Oregon Trail 227-grain roundnose. Many of those bullets showed signs of tipping on the paper targets. Perhaps that idea of crimping on the front driving band wasn’t so brilliant after all. With the other bullets, often a flyer ruined an otherwise tight four-shot group. The Colt Model 1917’s chamber mouths were measured with plug gauges. Five were uniformly .455 inch. The sixth was just shy of .457 inch. I say “shy of” because a .457-inch plug gauge would start into but not freely enter that chamber mouth. I’m surprised this Colt shot as good as it sometimes did with such large chamber mouths.

A great article idea just struck me. A great follow-up to a project like this would be using rimless .45 Auto cases in half- and full-moon clips. I will begin looking for those gadgets that help fill and empty clips and perhaps my S&W Model 1917 will be back in service by that time.

.jpg)