Blaser’s straight-pull R93 action smoothly gulps 375 H&H loads. This rifle is accurate.

The English gunmaking firm of

Holland & Holland introduced the 375 Belted Rimless Nitro Express in 1912. The new century promised tectonic shifts in hunting rifles. Until the 1890s, black powder and steels and rifle actions to bottle its modest pressures had limited bullet velocities. Hunters had depended on heavy bullets to kill Africa’s biggest beasts. Then, in 1889, James Dewar and Frederick Augustus Able developed cordite, a smokeless propellant named for its pale orange spaghetti-like strands.

The 375 H&H was the second belted cartridge from the Hollands’ shop. The 400/375 Belted Nitro Express preceded it in 1905. Like the 9.5mm Mannlicher-Schoenauer, a rimless cartridge that arrived about the same time, it sent 270-grain bullets at 2,150 (feet per second) fps. The belt established proper headspace on rimless cartridges without definite shoulders. Both the 400/375 and the 9.5 M-S lacked the power to kill thick-skinned African game reliably.

The elegant bottom metal on this Alaska Arms 375 Ruger Alaskan adds an extra round to a standard stack.

The 9.3x62mm was popular at the time and slowed acceptance of the 375 H&H, which required costly magnum actions. Also, the Holland shop had fielded its 375 as a proprietary round, chambered only in its own rifles. Not until the end of World War I was the 375 H&H released to the trade.

Early British loads for the 375 H&H – and its offspring, the 300 H&H Belted Rimless Nitro Express – were conservative: 62 grains of cordite to drive 235-grain bullets at 2,800 fps, 61 grains hurling 270-grain bullets at 2,650 and 58 grains sending 300 grainers at 2,500. Pressure: a modest 47,000 psi. Cordite’s nitroglycerine content made it temperature-sensitive. Most powerful British rifles of that day were bound for India and Africa, where tropical heat could bring breech-sticking pressures. A flanged (rimmed) 375 H&H Nitro Express with a longer 3.94-inch case was loaded to within 100 fps of the belted cartridge, for break-action rifles.

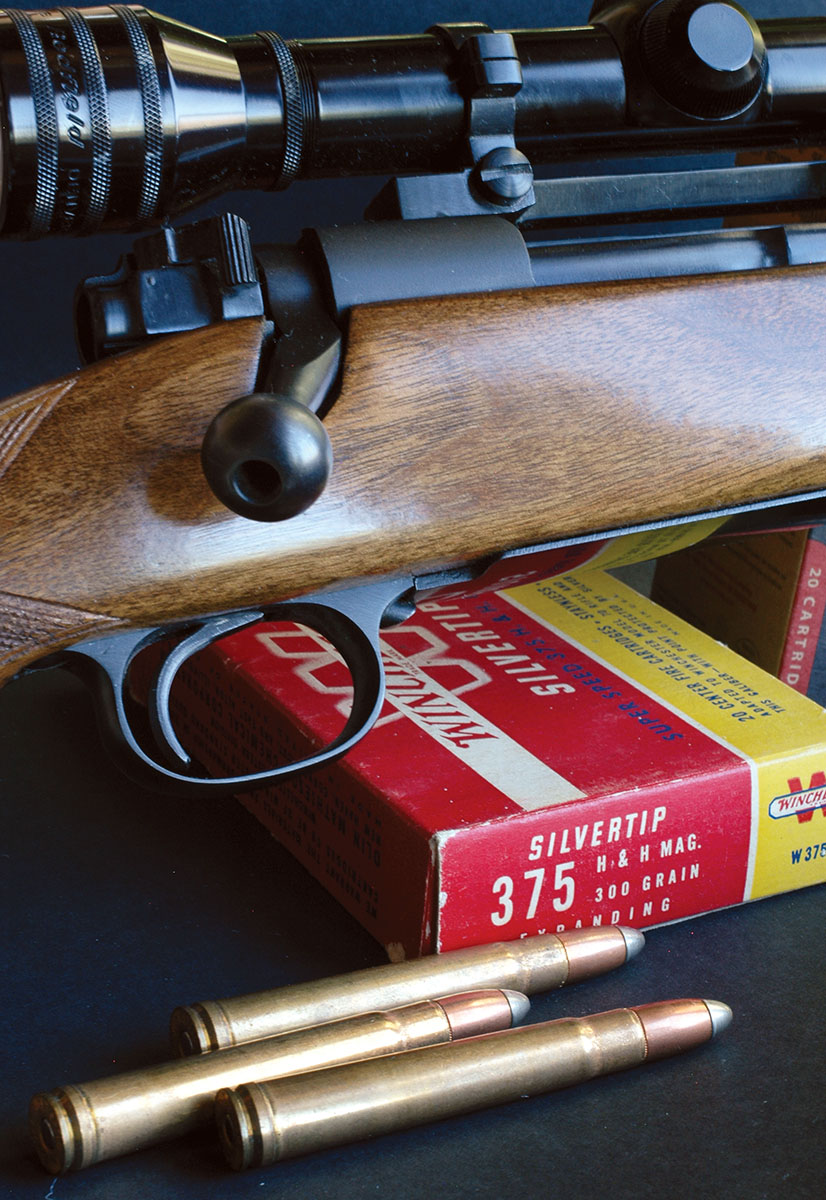

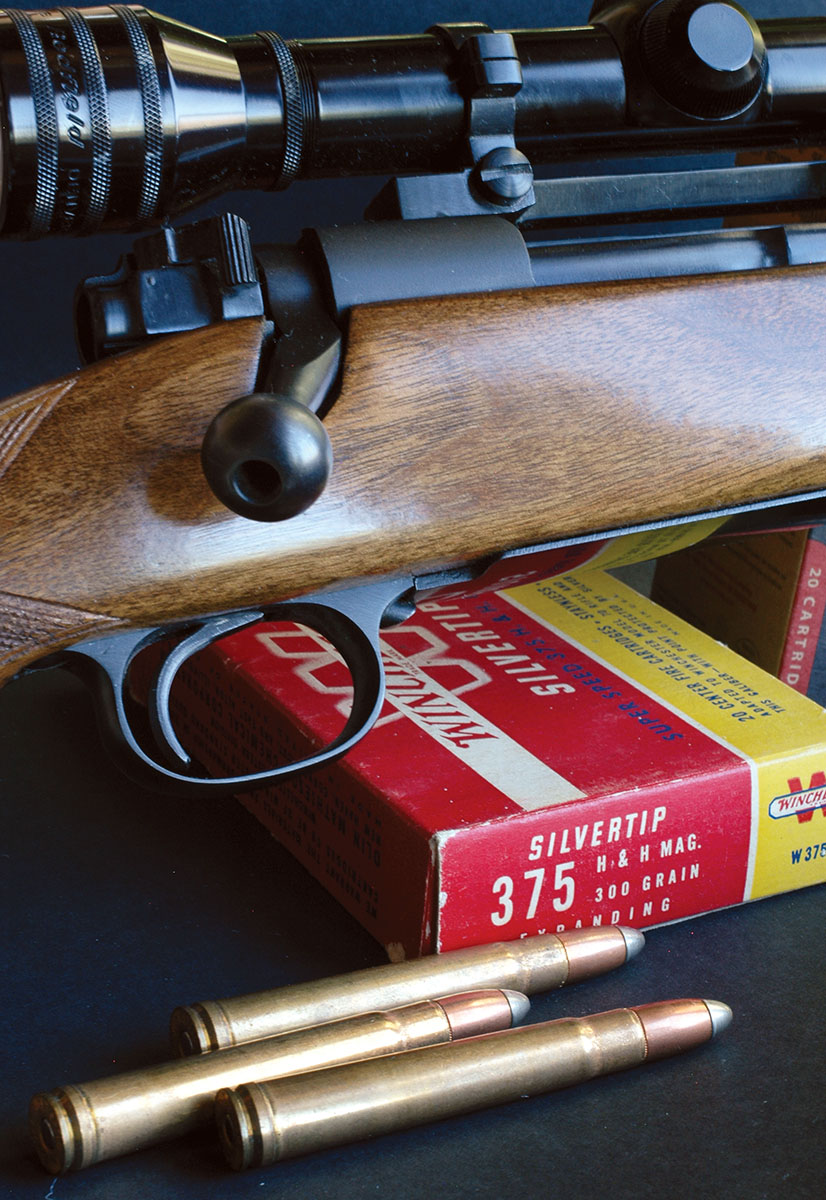

A late pre-64 M70 is shown with earlier loads. The Silvertip is not as strong a bullet as advertised.

First offered stateside by Western Cartridge Co. in 1925 as the 375 H&H Magnum, the big belted “medium-bore” had more power and recoil than deer hunters wanted. Sales were tepid. With its 2.85-inch case and a loaded length of 3.60 inches, the 375 didn’t fit repeating rifles designed for the 2.49-inch case and 3.34-inch overall loaded length of the 30-06. The 375’s .532-rim diameter was also greater than the 30-06’s .473 rim, so it begged a larger bolt face.

In the 1920s, New York’s prestigious riflemaker, Griffin & Howe, began barreling costly Magnum Mauser actions to the 375 H&H – and to the 300 H&H, which came ashore at the same time. Both made the charter list of chamberings for Winchester’s Model 70, which was announced to replace its Model 54 bolt rifle in 1936. Production of these rifles began in earnest the following year. The availability of a U.S.-made 375 “factory rifle” gave the cartridge market traction. The Model 70 in 375 sold initially for $78.45.

Winchester’s M70 was the first commercial 375 H&H of note stateside. Glassing the recoil lug of early rifles makes sense.

My first 375 H&H rifle was a secondhand Winchester with a split wrist, which I pinned and glued. In Africa, I used it with a tall brass bead front sight and a receiver-mounted Redfield aperture. It downed a variety of plains game and a buffalo that required more shots than it should have because I muffed the first.

Once, after observing an elephant cull, I asked the Zimbabwean rangers about their rifles. All but one carried 458s supplied by the government. The odd man out preferred his 375. “More penetration – and it won’t beat you up like a four-five-eight.” I had watched him kill an elephant quartering off. His 300-grain solid had exited the forehead after powering through neck and skull. Years later, the outcome of my first elephant hunt would hinge on such penetration.

Once scarce, affordable rifles in 375 H&H abound. This Weatherby Vanguard shoots well.

The 375’s original 235-grain softnose load faded. Stouter 250- to 270-grain bullets with higher sectional densities fly as fast in modern loads. Core-jacket bonding and partitioned cores help them through thick muscle and bone. Swift sells 250- and 270-grain A-Frames, Nosler 260-grain AccuBonds and Partitions. The Barnes TSX 270 grain is another top pick. Loaded well below red-line pressures, an AccuBond 260 grain traces the arc of a 180 from a 30-06 – and hits harder at 200 yards than the 30-06 bullet at the muzzle! A pal stokes 300-grain Partitions to 2,400 fps, noting they’re comfortable to fire in his Whitworth. “And deadly.” For big African beasts he pushes Barnes 300-grain X bullets at 2,500 fps with 71 grains of RL-15. He has recovered both bullets from tough game. “They went deep and mushroomed perfectly.”

Once few, factory loads for the 375 H&H have proliferated. Here’s a modest sample of the variety.

The standard 375 bullet for thick-skinned beasts is a 300-grain solid listed in most ammunition charts at 2,530 fps. Many hunters use softpoints of that heft to duplicate point of impact. Norma’s 350-grain Woodleigh solids clock only about 2,300 fps, but penetration is astonishing. A century ago, British gunmakers declared that the proper exit speed for a dangerous-game bullet was 2,150 fps. So maybe 2,300 isn’t slow!

Some hunters say the 375 H&H “knocks down” lesser game. Not true. Animals collapse when bullets scramble nerve centers or break supporting bones, or after vital organs are damaged to the point of fatal malfunction. Another myth is that big bullets waste meat. Unless they smash bone, expanding 300-grain 375 bullets designed for heavy game typically ruin less meat than faster bullets half that weight. A slow bullet is less violent in upset, imparting less explosive hydraulic force to surrounding tissue. It drives deeper but carves a narrower path.

The 375 Ruger’s short, thick powder column sends a 375 H&H punch from shorter actions and barrels. Its case holds roughly 10 percent more propellant.

One of the 375’s most endearing traits is its willingness to chamber. Long and tapered, with a 12¾-degree shoulder, the case feeds eagerly with any action long enough to accept it. There are many now, though Winchester had sales pretty much to itself for years. Remington listed its strong, economical Model 721 in 300 H&H at the rifle’s 1948 debut but didn’t add the 375 until 1961 – then built just 28 of these Kodiak rifles. Remington’s 700, announced the following year, chambered the 375 in various “safari” versions through 2015. Whitworth and Remington’s 798 rifles were built on M98 Mauser actions. Browning’s lovely High Power series, produced from 1960 to 1974, included 375s on FN Mausers. Sako bolt rifles came in 375 H&H as well. I once had a Model 85 accurate enough to pulverize Oreos at 200 yards. It also had superb open sights.

Wayne ranks Sako’s M85 among the best rifles in 375 H&H. Big game begs no tighter groups.

The 375 I’ve carried lately is a stainless model from the original Montana Rifle Co. shop, its receiver is an investment-cast Model 70 clone. The stock is a tad short for me and petite in the grip. But the rifle is lightning-quick and points naturally. On the trail of a stock-killing leopard some years ago, I kept abreast of trackers as they wound through increasingly dense thorn. The going was slow, the boys obscured by cover when the nearest screamed! I crashed through the bush toward him. He had frozen mid-step. By great good luck, a ray of sun lit a rosette in the tall grass. The 375 leaped to cheek; its softnose pierced the cat’s shoulders. With a sharp squall, the beast vaulted high in the air, landing dead 11 steps away.

The 375 H&H Belted Rimless Nitro Express so handily trumped other “medium-bores” of the day, few cartridges emerged to challenge it. It hit much harder than the 375 Flanged 2½-inch of 1899 and Eley’s 360 Nitro Express of 1905. Like the 400/375 Belted Nitro Express, these pushed 270-grain bullets at 2,050 to 2,200 fps. In 1922, Purdey announced its rimmed 369 Nitro-Express. It launched 270-grain bullets at 2,500 fps, about 100 fps behind the 375 H&H’s sidekick, the 375 Flanged Nitro-Express.

Commonly overlooked for dangerous-game rifles, Mossberg offers its nimble Patriot in 375 Ruger at a very attractive price. Wayne has shot 1-MOA groups with his.

Stateside, interest in 375-bore cartridges had followed the 38-55 into the sunset. Hunters craved speed. In 1944, Roy Weatherby’s 375 Magnum was offered both on a reshaped 375 H&H hull with minimum body taper and his signature radiused shoulder. A big bump in capacity opened the throttle on 270-grain bullets to a claimed 2,940 fps, with 300-grainers to 2,800. Handloading guru Phil Sharpe, declared the 375 Weatherby was so intimidating, “game almost dies before you pull the trigger.” But sales were never strong and fell off after the 1953 debut of Roy’s mighty 378. In 1960, he axed his 375.

The Montana Rifle Co. rifle Wayne uses in Africa is agile, quick to cheek and points naturally.

The most noteworthy 375 in more than a century is the 375 Ruger, developed with Hornady in 2006. Its 2.58-inch case is .27 shorter than its predecessor while the loaded length is 3.34 inches, the same as a 30-06.

The neck measures .305 above a 30-degree shoulder. Ruger’s 375 holds roughly 10 percent more fuel than the 375 H&H. It’s a belt-free design, with head diameter matching the .532 rim. A minimum taper puts the shoulder diameter at .515 inch, for a beefy powder column.

Loads for the toughest thick-skinned game: the 375 H&H with Woodleigh 300-grain solids.

Last year –

Hornady’s 75th – I asked Steve Hornady to name his favorite cartridge. “I’m proud of the .375 Ruger,” he said. “Our engineers designed it perfectly. And it’s sired our PRCs.”

Chart velocities for the 375 Ruger are about 5 percent faster than for the 375 H&H.

“You might think the .375 Ruger would swallow maximum .375 H&H loads with room to spare,” said Hornady’s Mitch Mittelstaedt, who helped develop the cartridge. “But if you start handloading the .375 Ruger with stiff charges for the .375 H&H, you court trouble. With almost any load, the Ruger produces nearly the same pressures as the H&H. Both are currently loaded to a maximum average pressure of 62,000 psi. They reach that bar with pretty much equal charges, depending on the powder.”

Wayne got this very satisfying group from handloads clocking an average 2,616 fps.

Why? “It is counter-intuitive,” conceded Mitch. “But we know shorter, thicker powder columns burn more efficiently. The .375 Ruger routinely out-paces the .375 H&H by 90 to 150 fps with identical charges of the same powder. Sometimes, we get surprises. H-4895, useful in both cartridges, hits the working pressure ceiling at just 68 grains in the Holland case and a velocity of 2,600 fps. In the .375 Ruger, we’ve loaded 72 grains of H-4895 and sent bullets quite a bit faster.”

Swift 260-grain A-Frames drilled this group at 2,720 fps. These are excellent mid-weight 375 bullets.

Mitch pointed out that throat dimensions affect pressures and velocities. “Bullets in 375 H&H factory loads aren’t far off the lands in a 2-degree throat. Standard chambers for the Ruger have a longer 1½-degree throat, and the bullet moves farther before engaging rifling.”

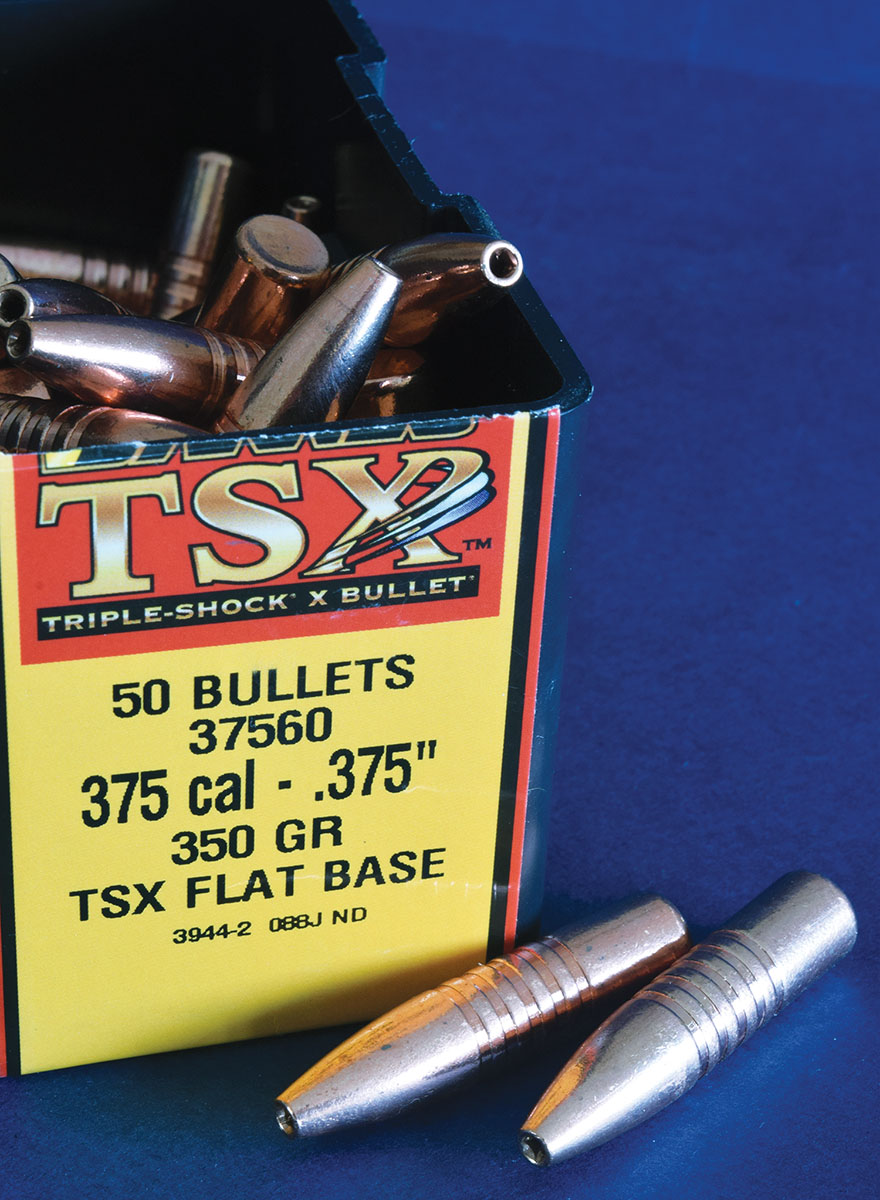

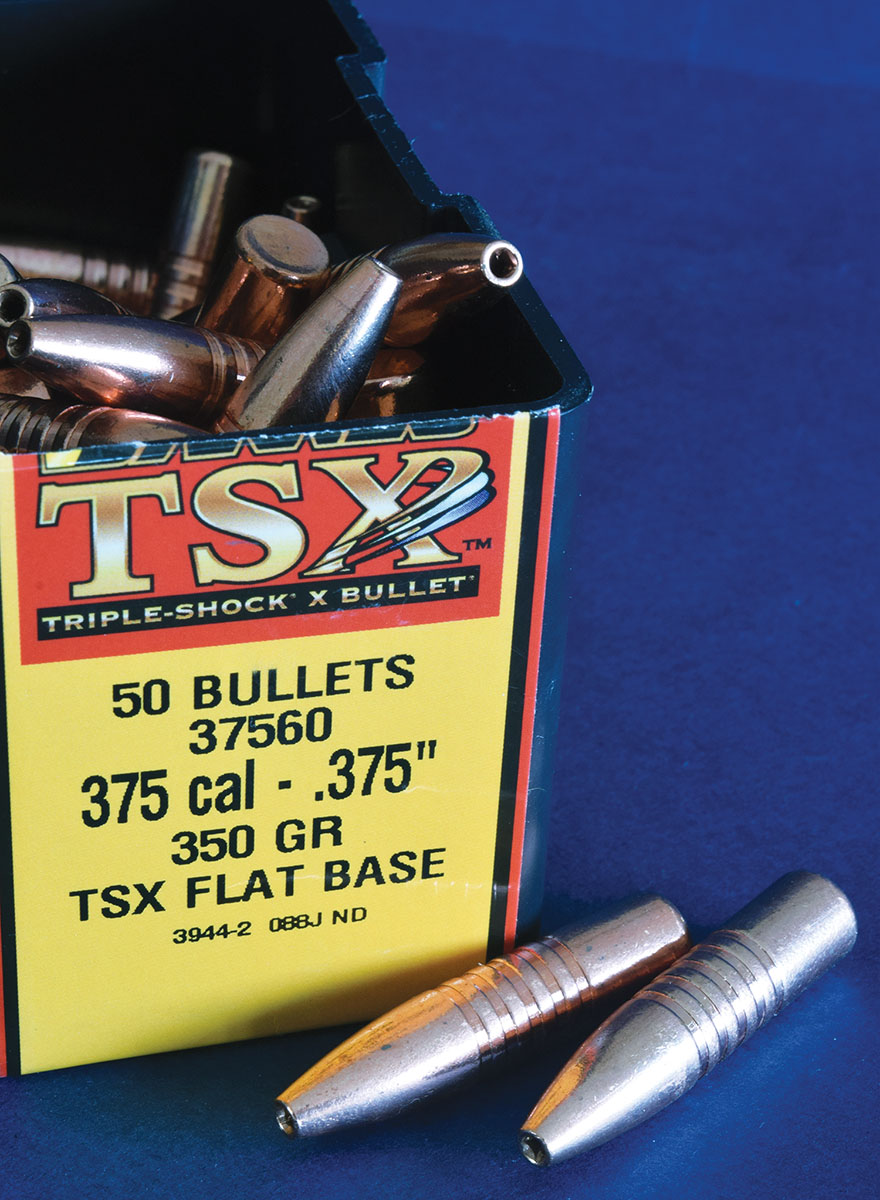

The 375 Barnes TSX are long bullets. Test their accuracy from standard 1:12 rifling before stocking up.

Mittelstaedt explained the purpose of designing the 375 Ruger wasn’t to upstage the 375 H&H. “It was to get H&H performance from a shorter barrel. We asked the .375 Ruger to deliver from a 20-inch barrel what the .375 H&H does from a 24-inch.”

Of several rifles in 375 Ruger that have crossed my path, including Ruger’s 77 Alaskan, one of the most impressive is a walnut-stocked Mossberg Patriot. Selling for around $400 at the time, it’s still a truly affordable 375. But it doesn’t feel cheap. The stock has clean, classic lines, with neatly stippled grip panels. Recoil pins bracket the magazine well. A Williams open sight pairs with a fiber-optic front on a short ramp. At 7¼ pounds with a slim 22-inch barrel, this rifle is lively in hand. The straight comb and cheekpiece, and a soft recoil pad, buffer its husky recoil. A detachable polymer magazine feeds a fluted twin-lug bolt with bolt-face extractor and ejector. The action cycles smoothly. Most 375 Ruger handloads I’ve chronographed have been fired in this Mossberg, which has put three bullets into one ragged hole. No hiccups, ever.

My Montana Rifle Co. rifle in 375 H&H is equally endearing. It has endured long days afield and most of my handloads.

Okay. It’s hard for me to find a rifle in 375 H&H or 375 Ruger that I don’t like.

.jpg)

.jpg)