In the original version of “Top Gun,” with Tom Cruise, I believe it is Cruise who utters the line, “I feel the need, the need for speed!” The same urge must have also struck the group of people who designed the 223 Winchester Super Short Magnum (WSSM). Speed like 3,850 feet per second (fps) for 55-grain bullets and handloads pushing 45-grain bullets near 4,500 fps! Are we heading for the rifleman’s Holy Grail that a cynic once described as a 50 Browning case necked to hold a phonograph needle?

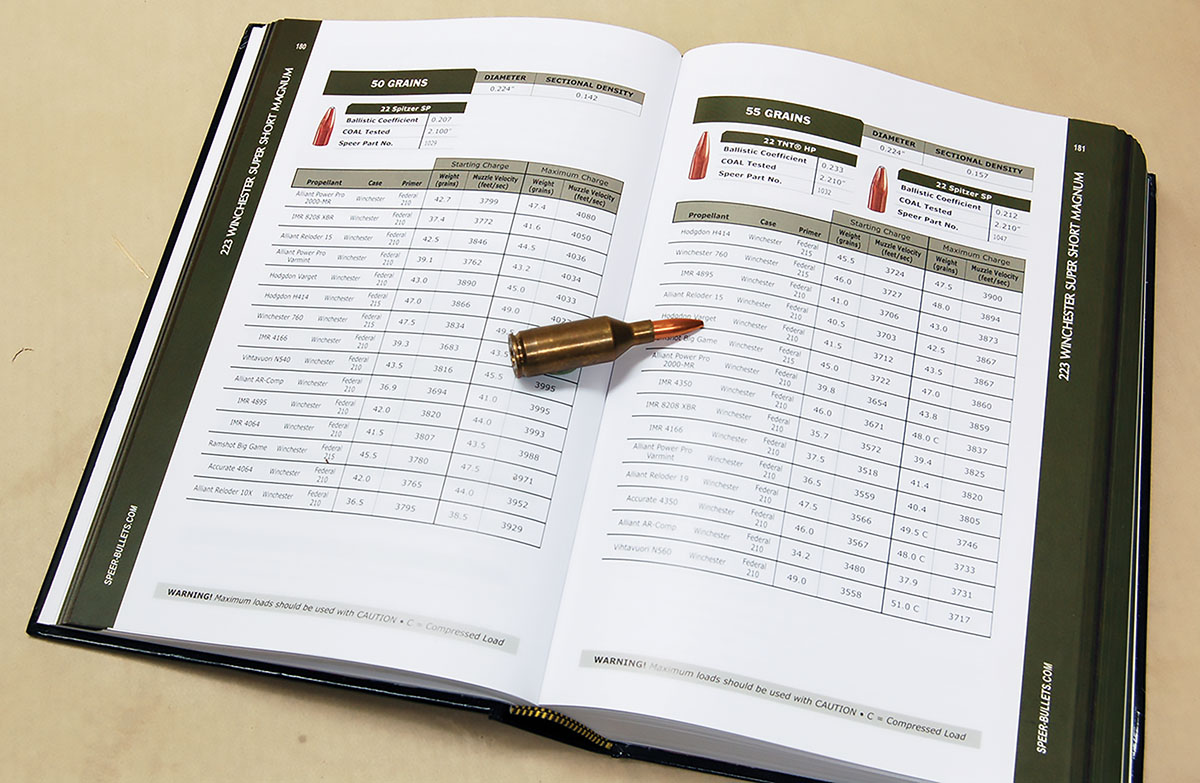

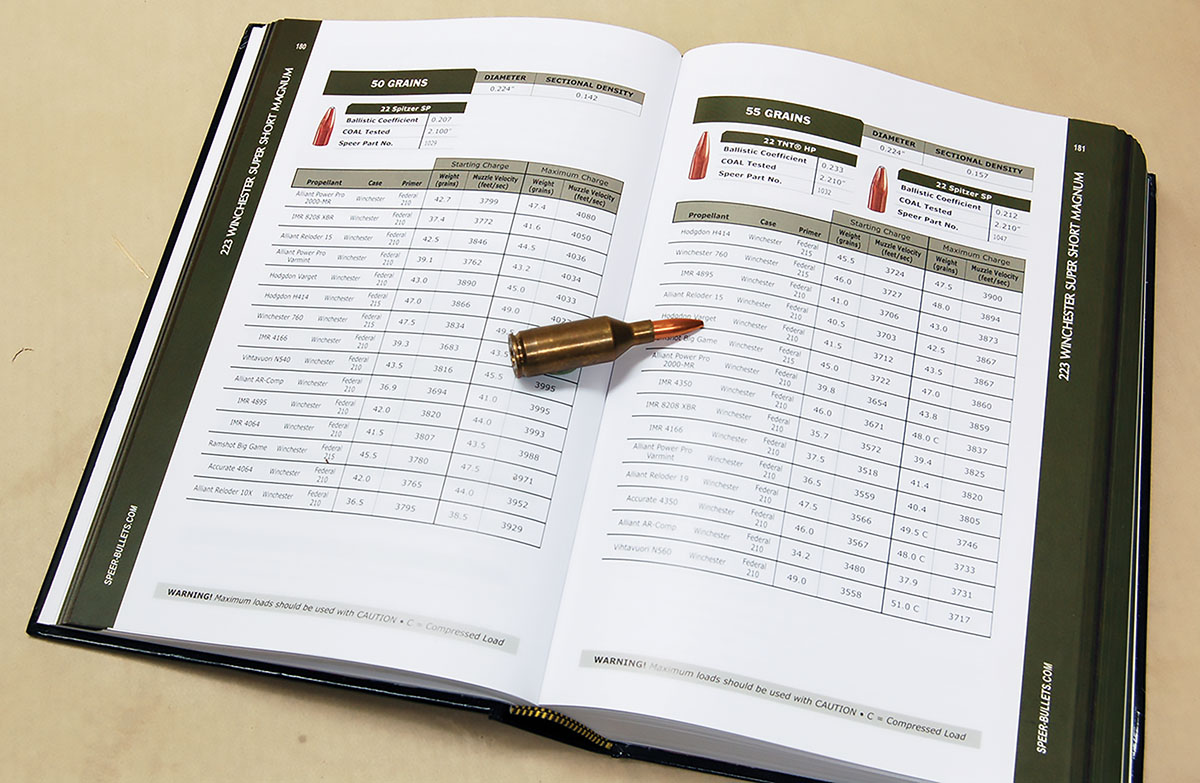

If ever there was a cartridge made for handloading, it’s the 223 WSSM. Ammunition and cases are hard to find. Stock up now!

Being named Super Short Magnum would seem to indicate there was already one or more cartridges officially titled Short Magnum. This was true, but you had to be alert to catch it because the Short Magnums referred to were only a year or two old. There were the 270 Winchester Short Magnum (WSM), 7MM WSM and 300 WSM.

Of course, this sounds strange to most riflefolk who, for at least 50 years referred to “short magnums” as rounds having belted cases 2.5 inches long (7mm Remington Magnum) as opposed to “full-length” 2.85-inch belted cases (375 H&H). So, are WSM cases belted, shorter than 2.5 inches, or what?

All WSM and WSSM cartridges essentially use the base dimensions of the old 404 Jeffery of 1905. After creating the round, Jeffery did not patent it, allowing any riflemaker to chamber it. This assured its popularity.

The 223 WSSM case rims are slightly rebated to fit belted magnum bolt faces without alteration.

It might also be mentioned that the base and rim diameters of the 404 are only a few thousandths of an inch longer than the belt and rim diameters of the later (1912) 375 H&H Magnum. It appears Holland applied its belted idea to the Jeffery case by reducing its body diameter to form the belt. However, it’s impossible to know for sure at this late date.

Though the huge 404 Jeffery case (19 percent greater capacity than the 375 H&H) had interested wildcatters for some time. The ending of British sporting ammunition production by about 1960, eliminated the supply of cases to play with. However, the 404 made on the Magnum Mauser action had become so popular that in a very short time, Dynamit-Nobel began ammunition production. The big, odd-sized case was saved.

In the wildcatting frenzy that took place in the U.S. and Canada after World War II, various forms of 20-rod (110 yards), 40-rod (220 yards) and 200-yard offhand target shooting were replaced by 100 and 200-yard “table shooting,” now called benchrest. This took most of the human element out of the equation. Groups got smaller as bullets, barrels and all other variables consistently improved.

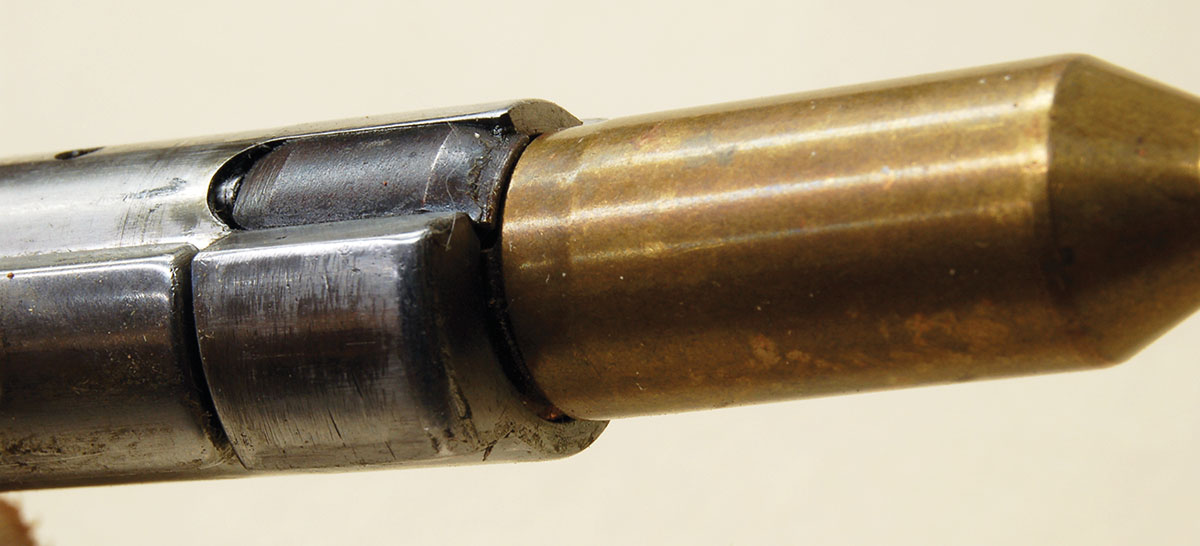

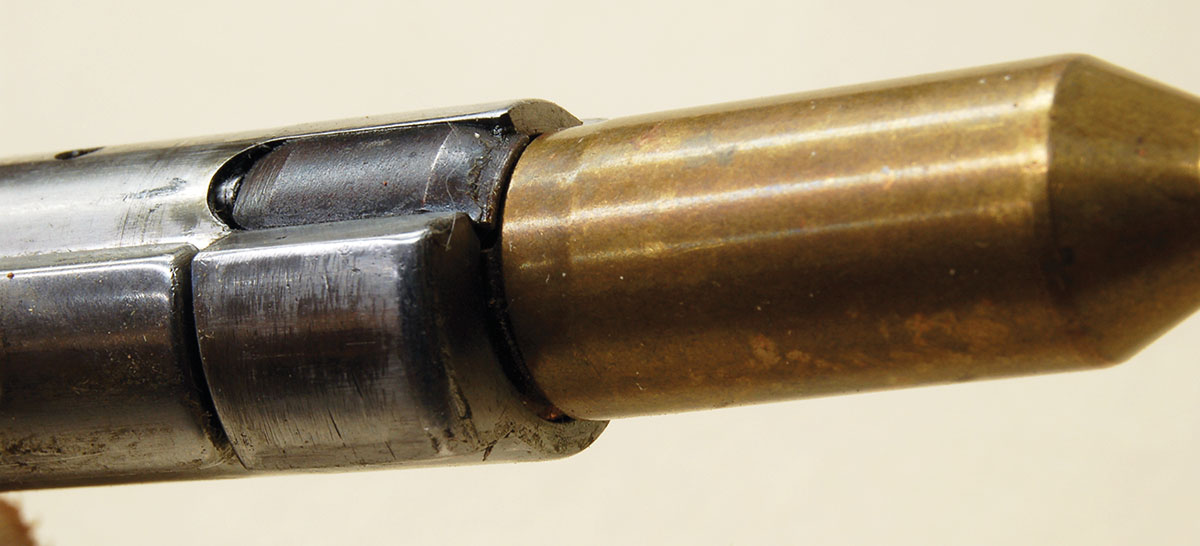

WSM and WSSM cases fit a standard belted magnum bolt face like this Sako 338 Winchester Magnum bolt.

Eventually, the discussion got around to case shape, a hot topic in the early years of the last century, as smokeless powder was being improved, but other problems were more obvious. As these were minimized, case shape again drew experimenters attention. In the 1970s and 1980s, cases with shorter and wider powder columns than normal seemed to produce smaller groups. Wildcats were created and tested. Some thought there was something to the ideas, while others stated it made no difference in group size.

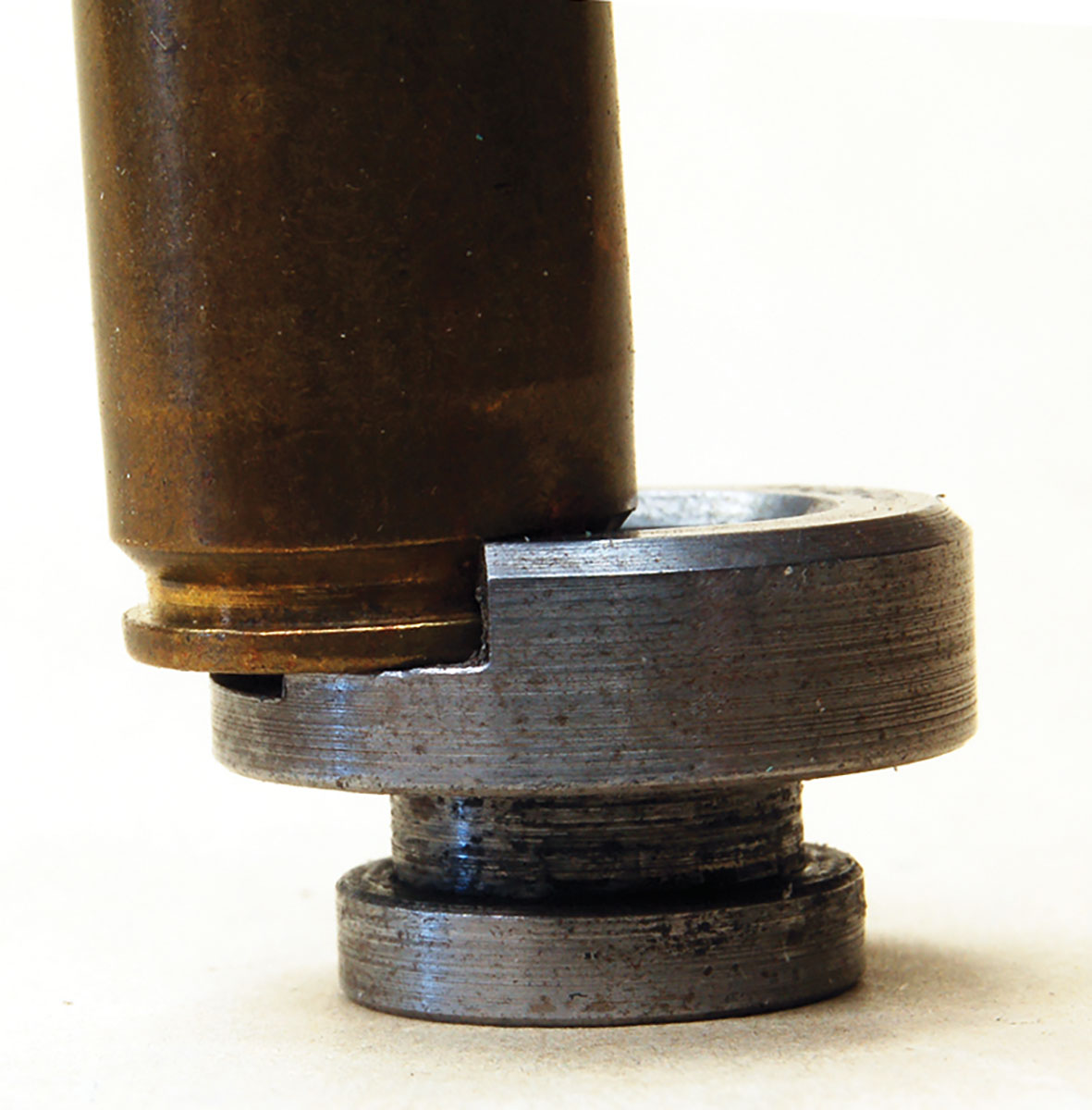

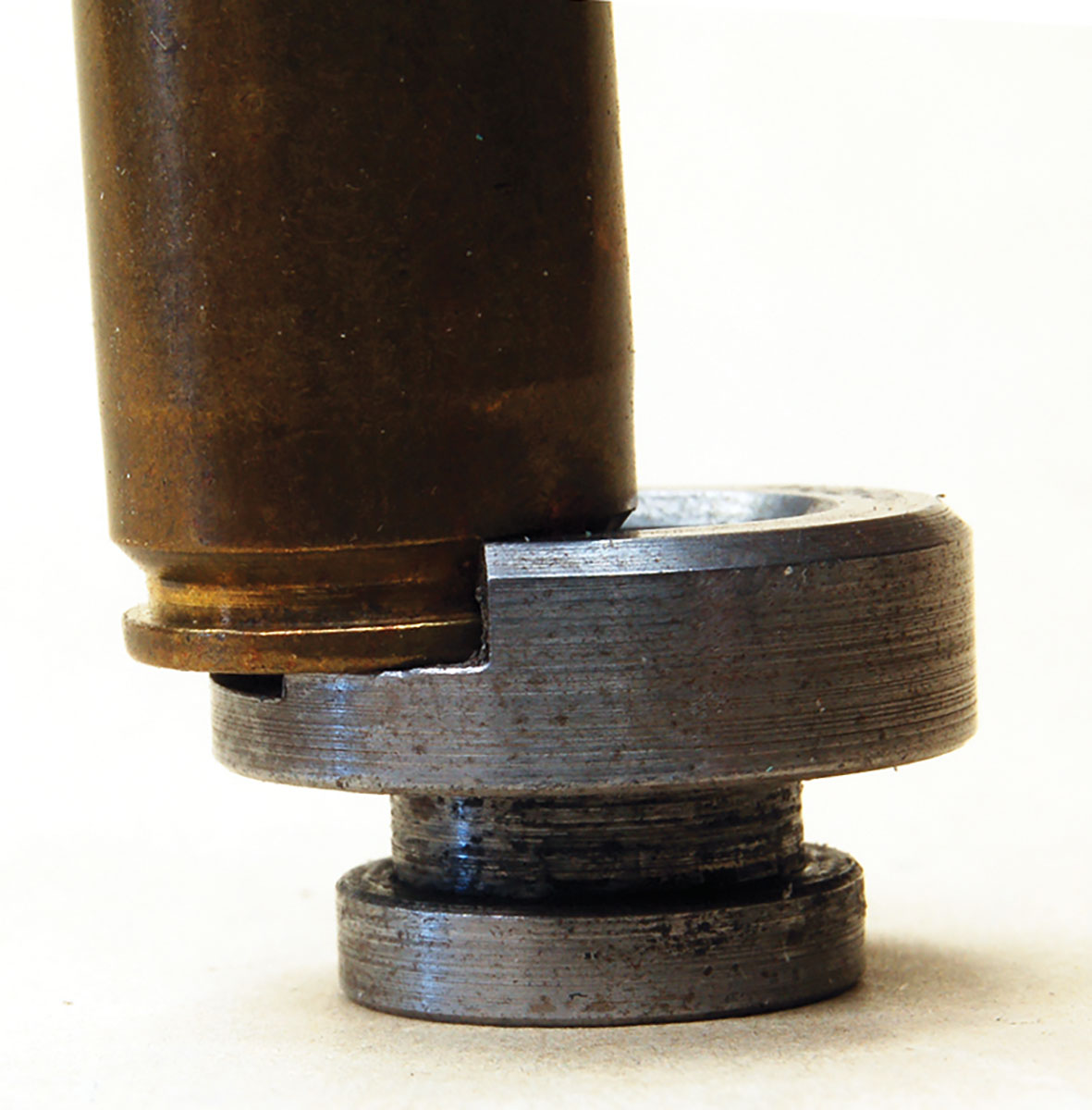

Neither the 223 WSSM nor any of the other WSSM or WSM rounds fit standard magnum shellholders because the extractor groove is .015-018 inch too shallow.

The problem here is that benchrest cartridges only need to give their bullets enough velocity to penetrate target paper. Thus, 22s and 6mms are used to reduce recoil. Also, the most accurate velocity range for individual bullets is known. This seems to be obtainable using roughly 22 to 29 grains of powder in a .440-inch base case like the 22 PPC. To rest the short, wide powder column theory, it would be necessary to take the next larger base case (30-06 at .470 inch), shape it like the 22 PPC and shorten it to under 1.5 inches in length. There are reports of turning the belts off magnum cases and then forming them to new shapes under 1.5 inches long. The project seems to have failed because of difficulty forming cases and non-uniform case wall thickness near the base.

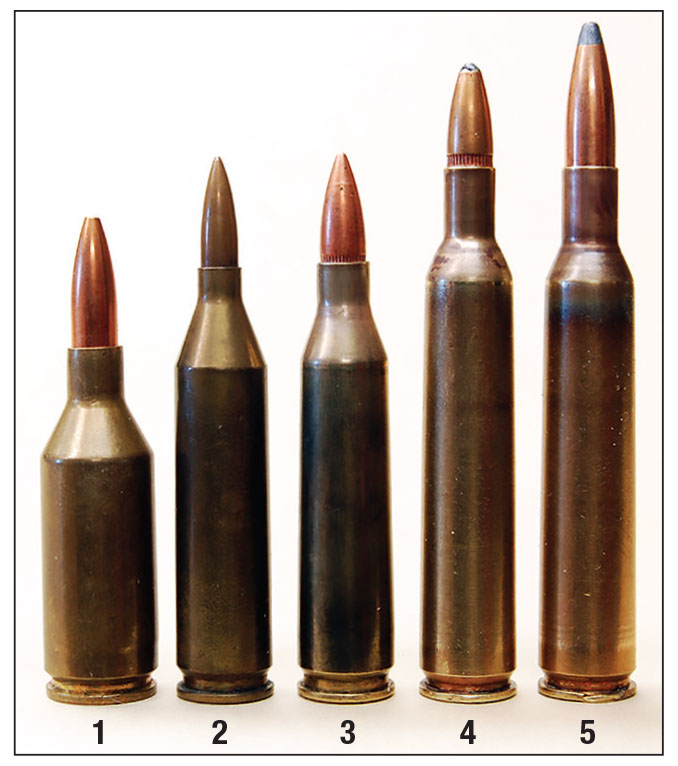

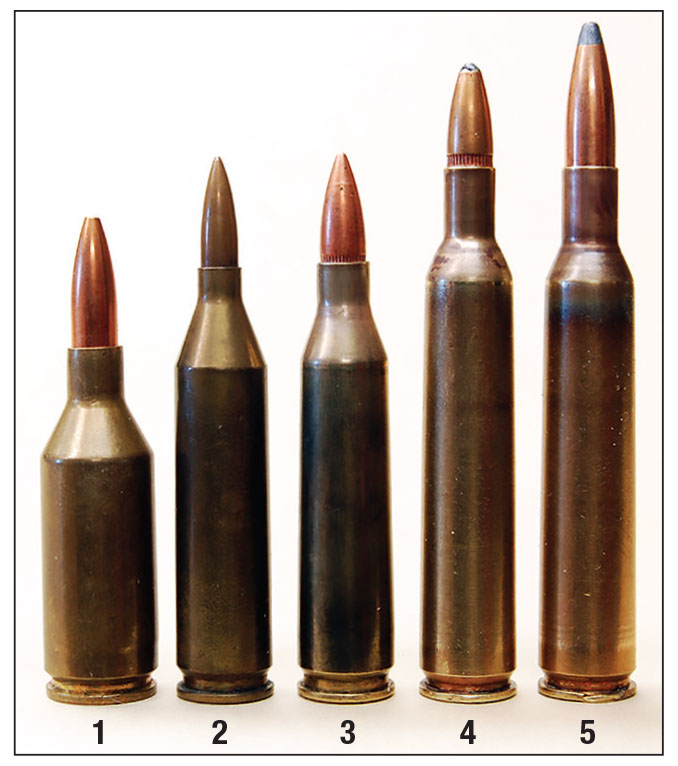

The (1) 404 Jeffery case became the (2) 300 WSM and then the (3) 223 WSSM.

Then, the somewhat unexpected appearance of the 223 WSSM and its sister round, the 243 WSSM (same exact case, different bullet diameter) happened in 2003. A means of answering the short, wide powder column question seemed to suddenly be at hand. The 223 WSSM case has a 404 Jeffery base (actually, a few thousandths of an inch larger at .55 inch) and a slightly rebated rim to fit standard magnum bolt faces. The length is 1.670 inches, making its capacity some 66 percent greater than the 22 PPC, about 20 percent more than the 22-250 and 17 percent over the 220 Swift.

This increase in capacity may be too much of a good thing for the finest accuracy. High loading density (eliminating air space above the powder charge) is also necessary for the best accuracy. Doing this with the 223 WSSM requires powder charges that drive benchrest-quality bullets far faster than ideal. It seems the case length would have to be shortened significantly to get capacity down for accuracy testing. Benchrest quality bullets are available in 6mm, so perhaps the 243 WSSM would be better for testing the short, wide powder column theory.

Cartridges ballistically similar to the (1) 223 WSSM have existed for years, but are wildcats such as the (2) 17-308, (3) 22-308, (4) 22-06, (5) 224 Weatherby Magnum and (6) 6mm-06.

Winchester apparently didn’t make the 223 WSSM for benchrest shooting, although the rumors of better accuracy from short, wide powder columns and shorter, stiffer actions wouldn’t hurt anything. Initial loads were listed as a 55-grain Ballistic Silvertip, a plastic-tipped bullet with a thick, solid base with heavy sidewall tapering toward the nose. The core is lead. A black coating covers the exterior. It exits the muzzle of a 24-inch barrel at 3,850 fps. Sighted-in at 200 yards, the bullet is 4.4 inches low at 300. That trajectory is only matched by the 220 Swift and 22-250 Remington using a 40-grain bullet and the 243 Winchester and 243 WSSM with 55-grain bullets. These light-for-caliber bullets, at their 4,000 fps plus velocities, produce spectacular kills close-up but offer no benefit past 250 or so yards.

Two other factory loads were originally offered for the 223 WSSM: a 55-grain pointed softpoint at 3,850 fps and a 64-grain Power Point at 3,600 fps, again from a 24-inch barrel. The first is a cup-and-core design, uniform jacket thickness and small exposed lead tip. It drops about half an inch more at 300 yards than the Ballistic Silvertip. The jacket of the 64-grain PowerPoint is quite thick in the rear half, tapering toward the exposed lead tip. The drop at 300 yards adds another inch. Presumably, it is intended for use on deer and hogs.

The (1) 223 WSSM and its factory competition: (2) 223 Remington, (3) 222 Remington Magnum, (4) 224 Weatherby and (5) 220 Swift.

Winchester ammunition still theoretically offers ammunition, but getting it is another matter. No other company, to my knowledge, has made 223 WSSM ammunition or cases. Only Winchester and Browning chambered rifles, but no longer. Some semi-custom makers still list it. Like many rounds that have appeared in the last 20 years, the 223 WSSM has become a handloader’s cartridge. Owners should lay in a supply of cases and/or ammunition whenever possible. It is highly doubtful that the case could be formed by necking down one of the Winchester Short Magnum series.

Basically, the 223 WSSM gives some 100 fps more speed than the 220 Swift (with handloads) by burning a few grains more powder. No one is interested. It now appears to have joined the ranks of similar super high-velocity rounds like the 22-308, 22-284 and 22-06.

.jpg)

.jpg)