The M350 from S&W

The Legend in a Revolver

feature By: Terry Wieland | June, 24

What could be more appropriate? Plus, with a top-quality revolver, a modern cartridge, and first-rate components, what could go wrong? As it turned out, almost everything.

An old pal who writes about handloading for another publication, having spent some time with the cartridge, suggested it should be called the “350 Spinach,” since no one likes spinach and he was convinced the 350 Legend would be just about as popular.

As it turned out, in the five years since its introduction in 2019, the 350 Legend has become very popular. It serves several useful purposes and is quite versatile in terms of loading – if that is, you can figure it out.

On the surface, the Legend’s history is straightforward: It was designed by Winchester to meet the demands of states that mandate a straight-walled case for deer hunting. Yet, they also wanted a cartridge that could be chambered and function properly, in an AR-platform rifle – hence, a rimless design. Rimless straight-walled cases are pretty thin on the ground, not least because they represent a significant headspacing problem.

Traditional rimmed straight-walls headspace on the rim; the rimless 9mm Luger and others headspace on the case mouth. This works well with short, squat cases – 9mm Luger, 45 ACP, 40 S&W – but the longer the case, the trickier it becomes.

The 495 A-Square headspaced on the belt, so headspace was not an issue, but this brings up the question of recoil and its effect on seated bullets in the magazine. In a gun with heavy recoil like the 495, bullets need to be firmly crimped to keep them from moving, either being pushed deeper into the case in a box or tubular magazine, or migrating forward in the case of a revolver. In the latter, bullet migration can tie up the cylinder in just one or two shots.

The 350 Legend is no 495 A-Square, but in terms of recoil, it’s no lightweight either. Its factory round fires a 170-grain bullet at 2,200 feet per second (fps) from a 20-inch rifle barrel. In an AR or bolt action like the Ruger Scout, weighing 7 to 8 pounds, it’s reasonably comfortable, but in a 4.5-pound revolver like the Smith & Wesson, not so much.

The 350 Legend case resembles a 223 Remington opened up, but it’s slightly shorter – closer in overall length to the 222 Remington. Instead of being a standard rimless case, it is actually rebated – again, almost indiscernible to the naked eye – designed to allow slightly greater case taper and hence ease of extraction. It has the same rim diameter as the 223 (.375 vs .374) but the head is larger (.389 vs .372). These were actual measurements taken from Hornady cases in both instances and vary slightly from the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) specifications, but this is not unusual.

One last point on case length: The 350 Legend is rated at pressures of 55,000 psi, considerably higher than the average revolver cartridge at 35,000 pounds per square inch (psi), and this leads to case stretching. Since it headspaces on the mouth, keeping 350 Legend cases trimmed to the proper length is essential. For those who are wondering, the full-moon clip does not hold the case in place; each round headspaces on the case mouth, braced between the front of the chamber and the standing breech. The clip’s only contribution is making it easier to unload.

The revolver in which this is chambered is the M350, a seven-rounder built on the massive X-frame. It weighs in, unloaded and without an optical sight, at 4.5 pounds. The 7.5-inch barrel is ported to reduce muzzle jump.

Several people asked whether it’s possible to shoot 38 Special, 357 Magnum, or 357 Maximum in it. My answer is, I don’t know and I don’t intend to find out by trying it. The most immediate objection is the base diameter. In the 38 Special family, the base diameter is .379, considerably smaller than the 350 Legend’s .389. Then, there is also the issue of bullet diameter, which is close, but not quite a match. If Smith & Wesson doesn’t say it can be done, then it shouldn’t be done.

Another consideration is the slight shoulder in the front of each chamber to provide headspacing on the case mouth, and that brings us to the last anomaly with the 350 Legend: Bullet diameter.

Bullets in the .35-caliber range come in a variety of diameters, each with its own purpose: the 9mm is .355, the 38 Special/357 Magnum are .357, and .35-caliber rifles, like the 35 Remington and 358 Winchester are .358. This is not cut and dried since you will find jacketed bullets for the 38 Special measuring .357 and cast bullets at .358. Some European 9mm rifle cartridges, like the 9x56 Mannlicher-Schönauer, use .356.

Every set of factory specifications I’ve seen for the 350 Legend insists the proper bullet diameter is .357, yet Hornady bullets, both the 165 and 170 grain, are .355.

Why did Winchester decide on .355?

One theory is that a slightly smaller bullet was needed to allow sufficient case taper for extraction, while still having substantial wall thickness at the mouth for headspacing.

Since I was loading only for the Smith & Wesson with its 7.5-inch barrel, not for a 20-inch barreled rifle, I stuck with bullets and powders most suitable for delivering optimum performance in a short barrel. I assumed the intended prey was whitetails and feral hogs.

Heavy bullets and slow powders – the usual approach for magnum rifle cartridges – are not going to work well. However, some heavy bullets (250 grains) on the market are specifically intended for subsonic big-game loads.

(As an experiment, I seated a .358- diameter cast semiwadcutter in a 350 case. It would not seat in the chamber without forcing it, which told me what I needed to know.)

As I write this, no data intended specifically for handguns (short barrels) has been published, so trying to tailor a load to a 7.5-inch barrel is a matter of picking among what’s available and hoping for the best.

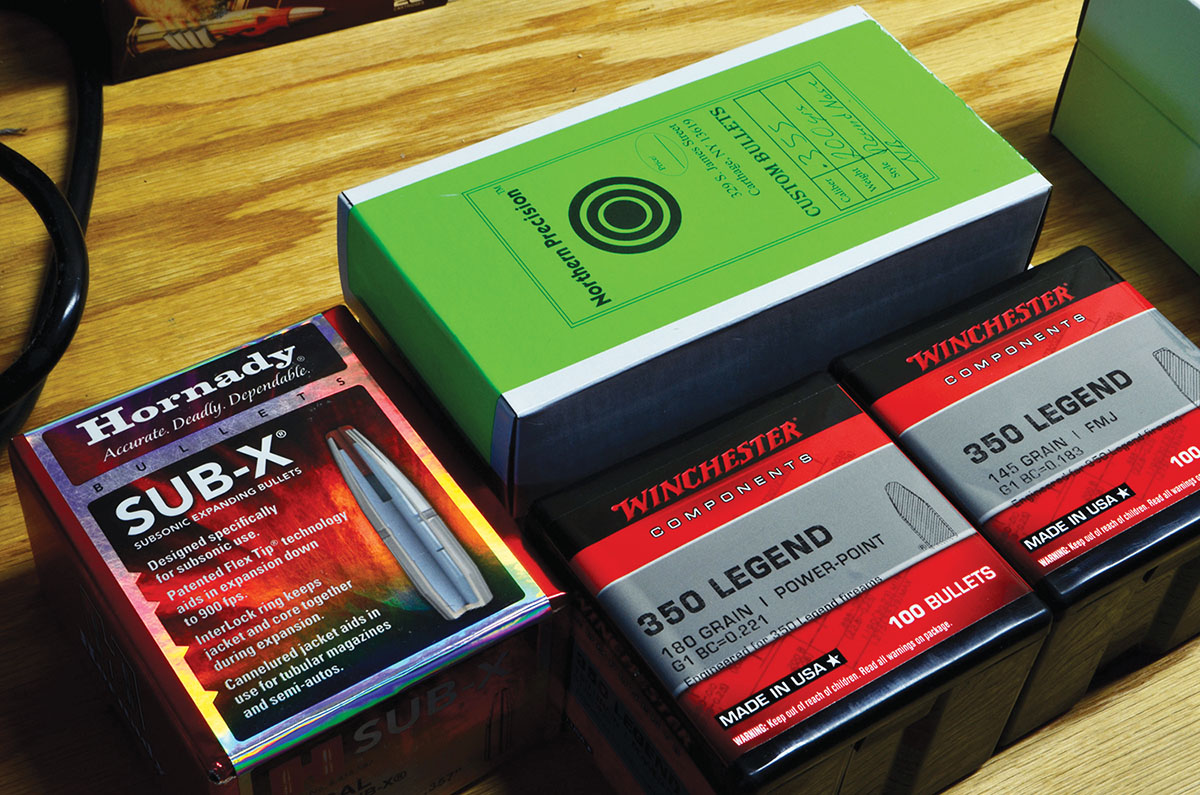

To winnow the available bullets, I went to the MidwayUSA website and ordered only those bullets specifically intended for the 350 Legend. These included Winchester’s 145-grain full metal jacket (FMJ) spire point and 180-grain Power-Points, and Hornady SUB-X 250-grain. To these, I added some bullets made by Bill Noody at Northern Precision, as well as a no-name 125-grain cast spire-point bullet, sized to .356.

Redding’s Series ‘D’ loading dies include an expander to bell the case mouth. The resizing die imparts a short, parallel neck. This is expanded to allow bullet seating without crumpling the case and the belling is then ironed out in the seating die, which also imparts a slight taper crimp. This procedure is familiar to anyone accustomed to loading conventional straight-cased cartridges.

I was using Hornady factory ammunition as well as new brass, and ran into a problem I had never encountered before. With once-fired brass, I could not seat primers without reaming the primer pocket. Brass from Hornady loaded ammunition required reaming. With their new brass there was no problem at all.

This is something to keep in mind, and not just with the 350 Legend. But it was one more pothole in the road that caused me to detest the cartridge.

Because of the cartridge’s high pressure, Small Rifle primers are recommended, and I used Federal GM205M throughout.

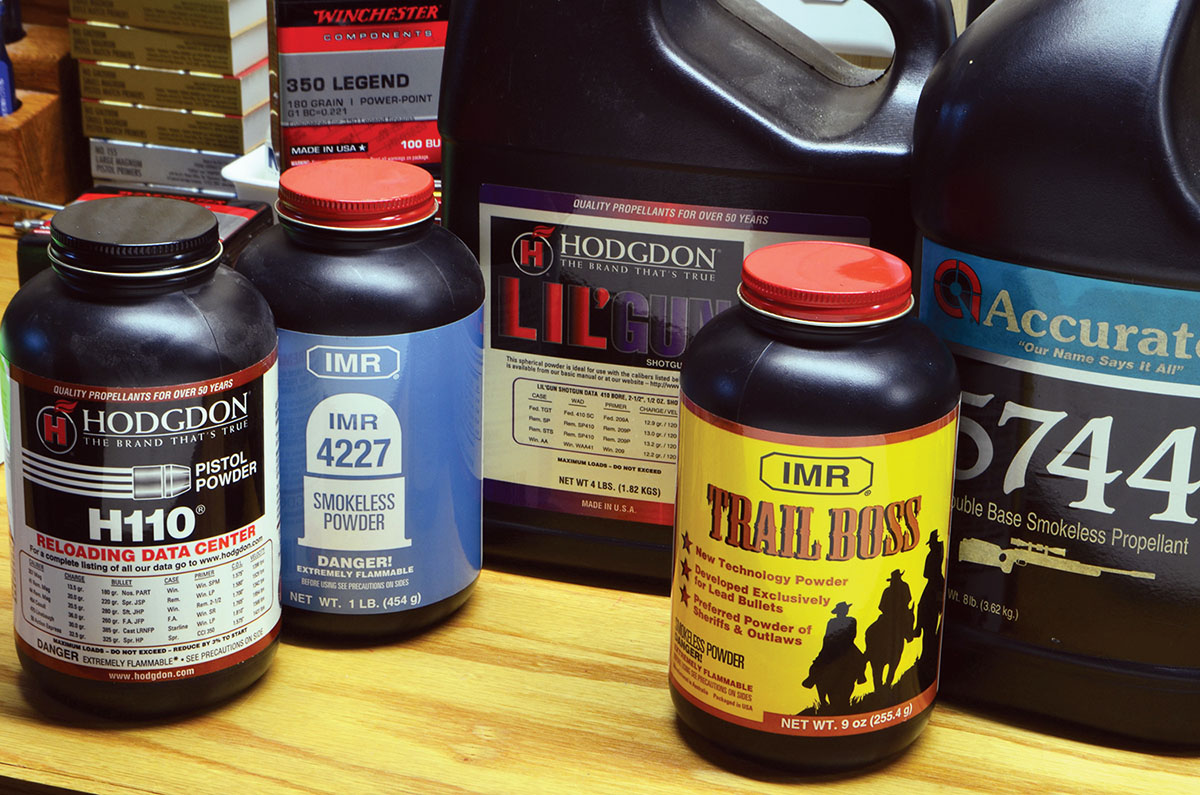

I settled on five different powders: IMR Trail Boss, 5744, H-110, Lil’Gun and IMR-4227. My efforts with Lil’Gun and the Winchester 145-grain FMJ were so fraught with unexplained anomalies that I left the results out altogether. Regarding accuracy, Trail Boss fared the best – albeit with very low velocities, while IMR-4227 delivered both velocity and accuracy with a Winchester 180-grain bullet.

Considering the 350 Legend’s stated purpose, the Winchester 180 is probably the bullet best suited to the cartridge.

Having said that, I was unable to match the performance of Hornady factory hunting ammunition in either power or accuracy with the time I had.

The accompanying table shows what you need to know to at least get started loading the 350 Legend for use in the Smith & Wesson M350, but I expect it would be more productive to wait until one of the powder or bullet companies does some pressure testing with the revolver and publishes loads suitable for its 7.5-inch barrel. As it is, working with existing load data intended for rifles is like shadow-boxing in the dark.

If I owned an M350 – which I don’t, and don’t intend to – and was going hunting, I would stick to factory ammunition, partly for performance but mostly for dependability.

This project did not work out as I expected or hoped, but it was nothing if not educational.

.jpg)