Loading 45 ACP in the 455 Webley Revolver

Adapt & Survive

feature By: Art Merrill | June, 24

One of the world’s longest-lived service revolvers, Great Britain’s “Pistol, Revolver No. 1, Mark VI, .455 inch,” which served that country and its commonwealths through two world wars, suffered a somewhat ignominious end on America’s military surplus market. At least, many of these Webley Mark VI revolvers did, though there are surviving original specimens that have not felt the touch of a mill. To Americans’ credit, the intent behind the permanent modification of the Webleys was to keep them shooting, and the modifications were a matter of practicality to achieve that.

“Mark VI” tells us that the revolver had five predecessor Marks, which go back as far as 1887, and each, of course, a modification of the previous one. Webley & Scott began manufacturing of the Mark VI in 1915, when it was immediately whisked onto active duty as England was already at war with Germany on the continent. In 1921, post-war production shifted to the Royal Small Arms Factory at Enfield Lock. The Mark VI soldiered on through World War II, after which it became available to American shooters as military surplus.

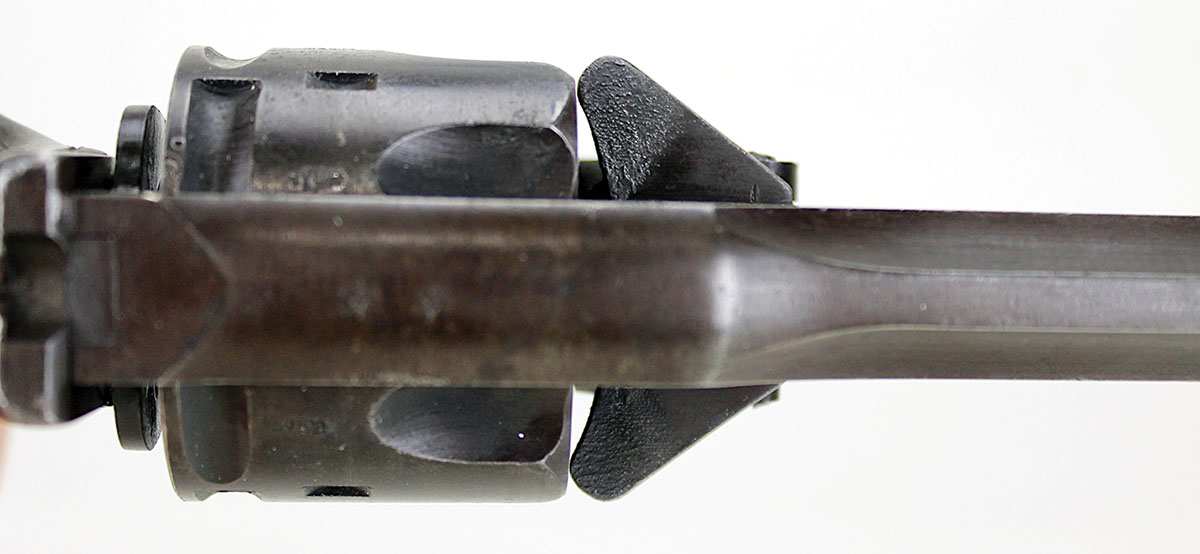

Webley’s Mark VI is distinctly 1800’s European. Its contemporary, the Colt Single Action revolver, seems positively streamlined compared to the clunky-looking Webley, which is barnacled with protruding parts. Whether all those protrusions are inelegant or represent a British sense of elegance, they all serve practical purposes. Angled “holster guides” on the cylinder retaining cam prevent the cylinder from hanging up on the holster edge when reholstering. Large screws on the left side retain the outside-mounted cam and lever that operate the automatic ejector and fasten the barrel assembly to the frame. A stirrup operated by a thumb lever and its attendant visible V spring locks the barrel to the frame. No less than a dozen visible screws hold the contraption together.

Webley’s Mark VI revolver wasn’t the only handgun factory chambered in 455 Webley. According to The W.H.B. Smith Classic Book of Pistols and Revolvers (Stackpole Books, 1968) Colt manufactured Bisley, Single Action Army and New Service Target revolvers, renaming the Webley cartridge “.455 Colt,” and Smith & Wesson chambered almost 69,000 “Mk II HE English Service” revolvers,based on the Triple Lock (First Model Hand Ejectors) and New Century Models, for British and Canadian forces in World War I. When the British declared the Pistol, Revolver No. 1, Mark VI, .455-inch Webley and its cartridge obsolete in 1946, many of the Mark VIs came to the U.S. as cheap surplus. A great many of these were commercially modified by milling off the rim at the back of the cylinder, which seems sacrilegious today from a historical sense, but made capitalistic sense at the time. Why? Because the downside to the inexpensive war surplus Webley is that 455 Webley ammunition was even then, as now, rare in the U.S., 455 Colt notwithstanding. The upside – by milling the extractor and the back of the cylinder, the revolver could be adapted to accept 45 Auto Rim or moon-clipped 45 ACP cartridges. The downside – factory loadings for both cartridges are too hot for the old break-action wheelgun. An upside – handloading.

Like the Webley revolver, the 455 Webley cartridge went through six permutations since its first introduction in 1891, which the British labeled, coincidentally and logically enough, Marks I through VI. Black powder launched the 265-grain lead bullet of the Mk I cartridge; that changed to cordite propellant six years later in the Mk II, which also had the case shortened about one-tenth of an inch. The Mk III of 1898 featured a lighter 218-grain “manstopper” bullet that looked a bit like a double-ended wadcutter with a hollowbase at each end. The Hague Convention of 1899, which prohibited hollowpoint bullets, meant that if the British military ever used the Mk III cartridge, it was only for a very short time. The Mk IV bullet of 1912 became a full wadcutter, dispensing with the hollows in the ends, and weight went up to 220 grains. The Mk V, with a hardened lead bullet, saw service only in 1914, when the Brits went back to the Mk II for World War I. Just in time for World War II, the MK VI cartridge finally got a heavyweight full metal jacket bullet of 265 grains in 1939 and utilized either cordite or nitrocellulose powder. The muzzle velocity of the latter incarnation is 600 feet per second (fps) or 650 fps, depending upon the resource consulted, or perhaps whether smokeless powder or cordite was used.

As an aside, the bullet weight of the British-manufactured military MK I, MK II and MK VI cartridges apparently could vary from 263 to 267 grains; publications almost universally split the difference at assigning them 265-grain bullets.

Webley’s cartridge never really caught on with American shooters, even when renamed 455 Colt (it was also called 455 Target, 455 Eley and 455 Revolver C.F.). Today, Fiocchi appears to be the only big-name manufacturer of 455 Webley, but the retail cost for a 50-round box at this writing exceeds $70. Enter the 45 ACP and 45 Auto Rim.

Though certainly familiar with the 45 ACP, many handloaders can’t say the same about the 45 Auto Rim (or 45 AR) cartridge. Someone may have told you, “The .45 Auto Rim is just a .45 ACP with a rim,” which is essentially true but isn’t the whole story. Yes, it was designed specifically for Model 1917 revolvers chambered for the 45 ACP round, but it was actually loaded to a lower pressure than 45 ACP. The U.S. government adopted the 45 ACP along with the Colt Model 1911 pistol of that year, and when World War I came ‘round a few years later, it spotlighted a severe shortage of military handguns. The government contracted with Smith & Wesson and Colt to supply revolvers chambered in 45 ACP, and it subsequently designated many of those revolvers at war’s end as military surplus.

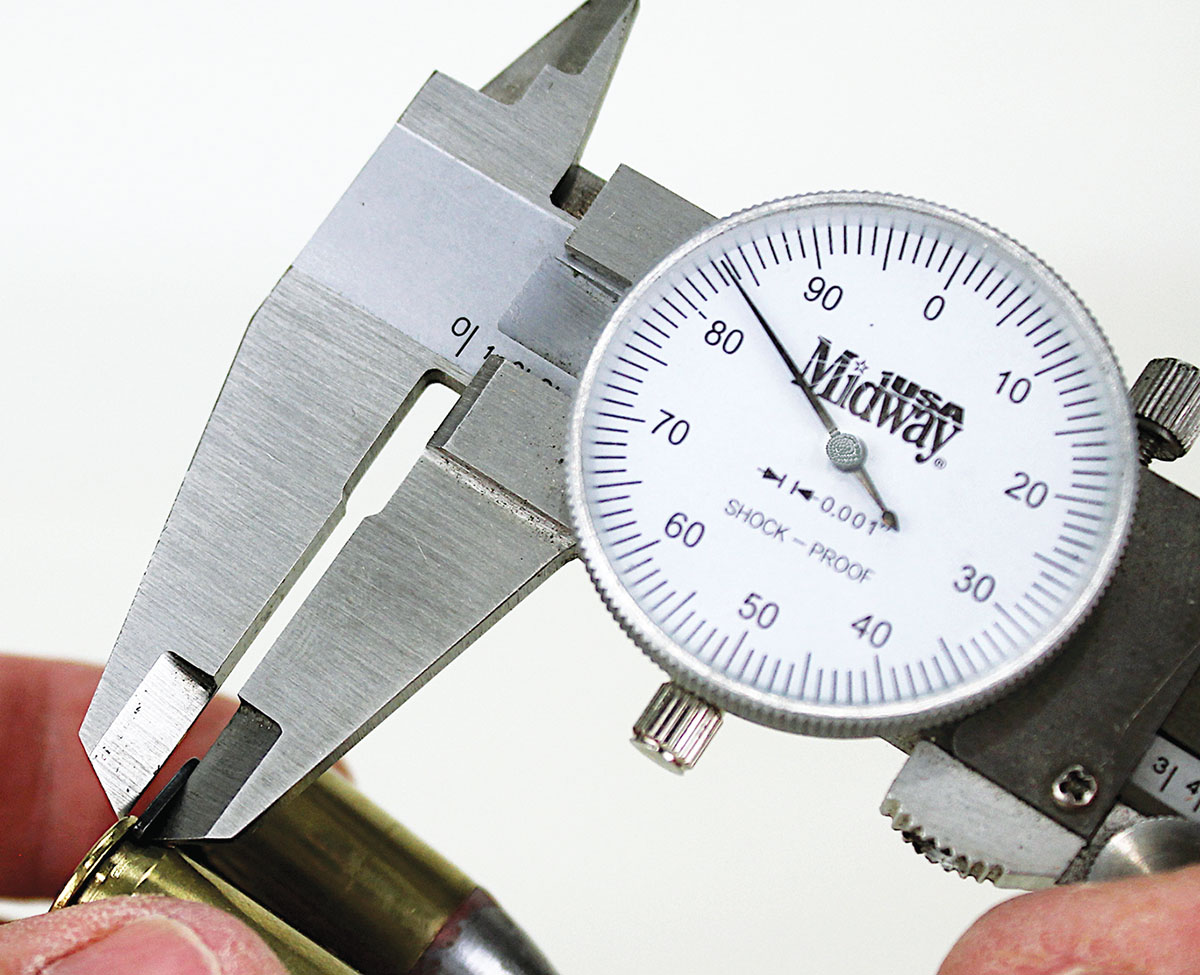

Being rimless and chambering on the case mouth, the 45 ACP cartridge needed full or half-moon clips to work in revolvers like the M1917s originally designed for rimmed cartridges. Moon clips, to the U.S. Army, were disposable, but not so much to civilians; they were one more thing to get lost and the revolvers were useless without them, so in 1920, the Peters Cartridge Company put a .089-inch thick rim on the 45 ACP case to eliminate the moon clip, and dubbed it 45 Auto Rim. The rim thickness of the 45 ACP is .049 inch, while moon clips add another .040 inch, more or less, depending upon the specific manufacturer, making an ostensible total thickness of .089 inch. Here, clips and WCC-headstamped military surplus brass measured .084 inch and worked perfectly.

The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute (SAAMI) doesn’t list the 455 Webley. However, Europe’s SAAMI equivalent, the Permanent International Commission for the Test of Small Arms, lists a maximum average pressure (MAP) of 900 bar for the Mk II cartridge, which equates to 13,053 pounds per square inch. The lead bullet Mk II and FMJ Mk VI ammunition, recall, both had a 265-grain bullet started at 600 and 650 fps respectively, so, there’s our handloading safety velocity/pressure speed limit for that weight bullet in the Webley.

Note that both 45 ACP and 45 Auto Rim standard factory loadings, though safe in the stronger Model 1917 revolvers, are a bit too hot for the top-break Webley Mark VI revolver. To reemphasize, it is potentially unsafe to fire factory-loaded 45 ACP or 45 Auto Rim in the Webley Mark VI revolver.

The bullet diameter of the .455 Webley MK II and MK VI apparently had a tolerance of .453 to .457 inch. Slugging the Mark VI revolver at hand showed an odd number of lands and grooves, which unfortunately means there’s no way to readily accurately determine bore and groove diameters, though the latter is given as .457 to .458 inch. Another aspect of this exercise, was to see if .452-inch 45 ACP bullets will produce acceptable accuracy in the 455 Webley revolver.

Common .452-inch bullets used here include a 200-grain lead semiwadcutter (LSWC) and Western Nevada’s 250-grain lead roundnose flatpoint (RNFP) bullet. I purchased online custom cast .455-inch, 260-grain hollowbase roundnose (HBRN) bullets intended specifically for the Webley to compare to the performance of the .452-inch bullets. The Fiocchi 455 Webley ammunition chambered and shot without a problem in the modified Webley, and in the table provides a baseline for comparison.

Case capacity of the 455 Webley is slightly less than the 45 Auto Rim and 45 ACP, which are identical (of course, there may be tiny differences between one manufacturer and another):

- 455 Webley..........1.30cc

- 45 Auto Rim.........1.48cc

- 45 ACP.................1.48cc

Because Boyle’s Law stated that pressure drops with an increase in volume, and because the 45 ACP cases have greater case volume than the 455 Webley, we could logically surmise that loads in the 45 ACP cases that do not exceed 650 fps with the 250- and 260-grain bullets should not produce peak pressures too high (>13,053 psi) for the Webley Mark VI revolver.

As the 45 Auto Rim case is dimensionally identical to the 45 ACP, loading manuals agree that load data for one case is directly interchangeable with the other. With no other published load data on hand for 250-grain bullets in the 45 ACP or 45 Auto Rim, I began by reducing the Lyman Reloading Handbook 49th Edition 45 ACP 225-grain lead bullet starting charges of Unique and W-231 by 10 percent. I stopped increasing charges when I flirted with the 600-650 fps mark. For lighter 200-grain LSWC bullets, 700 fps seemed a prudent maximum velocity.

While many of the Webley’s ultimately sold on the post-war military surplus market here, ammunition makers apparently believed there weren’t enough to warrant the cost of tooling up to manufacture its proprietary cartridge. The same can be said of perhaps all European military handgun cartridges outside the 9mm Luger. The Webley Mark VI survives as a shooter because it was able to adapt to an American cartridge.

.jpg)

.jpg)