41 Long Colt

In Search of Accuracy

feature By: Mike Venturino Photos by Yvonne Venturino | August, 24

My experienced-based opinion is that the 41 Long Colt is a paradox, a conundrum, a mystery, a success, a missed opportunity and most of all – a very interesting cartridge. Let’s look at those words. My desk thesaurus lists absurdity as a synonym for “paradox.” It is absurd to have a cartridge with a bullet nominally .386 inch in diameter for use in handguns with a nominal barrel groove diameter of .401/402 inch. “Conundrum” is a synonym for puzzle. It’s puzzling to logical minds why a cartridge using .38-caliber bullets would be named 41. A “mystery” is why Colt’s engineers did not reduce revolver barrel dimensions to match the 41 Long Colt’s bullets. “Success” is that 41 Long Colt gained such popularity that revolvers chambered for it were made in the tens of thousands including Colt’s Single Action Army, Model 1877DA, and Army and Navy Specials. In fact, 41 Long Colt was in fifth place of the SAA in terms of numbers produced. Factory loads for 41 Long Colt were produced at least until the mid-twentieth century.

Lastly, “interesting” is a subjective term. Indeed, most modern handloaders are put off by the necessity of assembling 41 Long Colts with soft hollowbase bullets that must expand at least .015 inch in order to grip revolver barrel rifling. The only alternative is a heel-base, outside-lubed bullet for which a special crimping tool must be used if shooting them over smokeless powders. I understand all that, but I’m drawn to such historical oddities as a moth to flame. Therefore, in 2020, when a fine-looking 1901 vintage 41 Colt SAA with 5½-inch barrel appeared for sale online, I bought it.

According to Suydam, in 1895, the second version of 41 Long Colt factory loads appeared. Bullets were inside lubed, 195/200 grains, with full bullet diameter inside the case. The black-powder charge remained the same. Because the bullet length inside the case reduced usable volume, case length had to be increased to nominal 1.13 inches. The overall cartridge length remained about 1.40 inches. This is where the bullets were reduced to true .38 caliber and given deep hollow bases. If a revolver was ever caliber stamped 41 Long Colt, I’ve never seen it. Each one I’ve examined has been marked simply 41 Colt.

As soon as my new Colt SAA arrived in 2020, its barrel and chamber mouth were checked by slugging the former and using plug gauges on the latter. All six chamber mouths were .410 inch and the barrel’s slug measured .401 inch. Although this SAA left the factory in 1901, I’d rate bore condition as 98 percent. Noteworthy is that the chambers were bored straight through with no “neck” or “ball seat.”

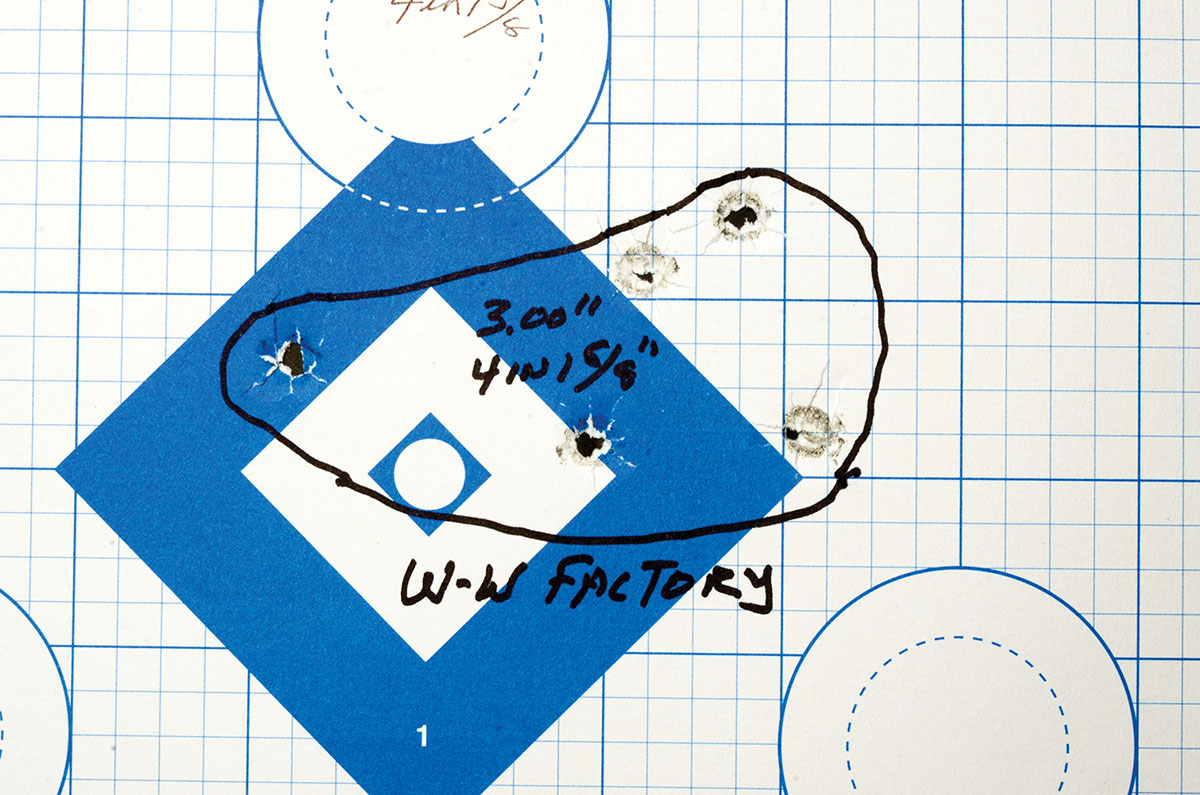

Leftover from earlier 41 Long Colt forays was a single 50-round box of Winchester factory loads. According to hearsay, someone special ordered a million 41 Long Colt rounds about 1976. They were loaded with 200-grain Lubaloy roundnose bullets and packaged in plain white boxes. Some were fired from my new Colt, giving velocities of 700 to 725 feet per second (fps) depending on the exact day. Searching the internet, a vintage box of Winchester factory loads was found. Five of those clocked at 712 fps. The bullets were 196-grain roundnose. Both factory loads had .386 inch hollowbase bullets and gave machine rest five-shot groups at 25 yards (usually) of 21⁄2 inches to 23⁄4 inches Peters’. Knowing this revolver was capable of at least of decent accuracy I progressed down the .41 LC handloading trail. It wasn’t smooth sailing.

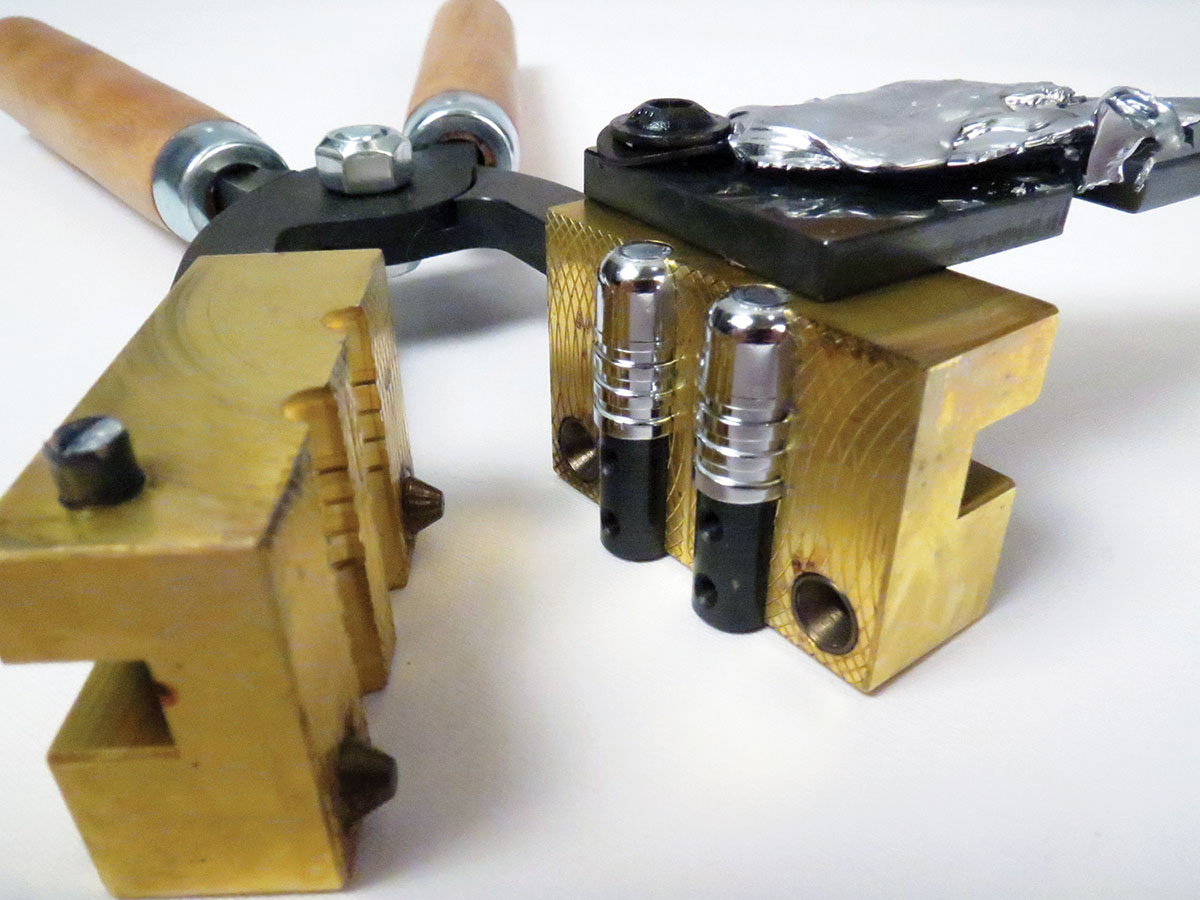

Bullets were more difficult, or should I say, finding proper bullet moulds was more difficult. A perusal of the internet showed no used Lyman or Rapine HB moulds for sale but I discovered a mould maker named MP Molds in Slovenia. (Yes, in Europe.) Fearing an extended wait time, I rather shakily ordered their 41LC-200HB double-cavity brass mould. To my great surprise and pleasure, it was in my hands in a week. It drops smooth 192-grain bullets of 1:20 tin-to-lead alloy or 196-grain ones of pure lead. However, the cast diameter of the pure lead bullets was only .385 inch, with the 1:20 alloy ones measuring .386 inch. Simultaneous with ordering the MP mould, an order was placed to Buffalo Arms for a custom-made .386-inch lube/sizing die.

My attitude was that reloading dies would be trouble free. Not hardly! They turned out to be the most frustrating part of this project. First, I purchased the Redding dies. Dropping .386-inch bullets in cases full-length sized resulted in bullets simply dropping all the way into the case. Although belling case mouths was unnecessary, that die’s stem was measured. It was .389 inch in diameter. The only good news was that if I could get an MP bullet to stick in place the seating/crimping die would apply a healthy crimp. Results were less than stellar with some bullets hitting where aimed and others soaring off into the ether. Shooting loose-fitting HB bullets with smokeless powders is not a recipe for good accuracy. My guess is there was a glitch at the Redding factory on this particular set of dies, as others have told me there were no problems with their Redding dies.

Then, my stubbornness (or obsessiveness) came into play. I began to check eBay every day and it paid off, albeit again at great expense. Eventually, I found both Lyman No. 386178 and Rapine No. 386195 HP moulds. Sticking with 1:20 alloy, Rapine bullets dropped at 185 grains and .386 inch in diameter. Conversely, the Lyman mould dropped .389-inch bullets but they weighed only 175 grains instead of Lyman’s old manual’s nominal 200 grains. Sizing those Lyman bullets in a .386-inch die literally wiped out its lube grooves. Therefore, a .388-inch lube/sizing die order was placed with Buffalo Arms. Common wisdom with HB bullets says to use pure lead, but in my situation, pure lead simply resulted in bullets that were too small for my reloading dies. My 1:20 tin-to-lead alloy actually works better.

Also found on eBay was something I did not know existed – Lyman 41 Long Colt reloading dies. Lyman discontinued them in the late 1970s. They sized cases down nicely so all bullets fit tightly after being belled with the .383-inch seating stem. I was finally happy – for a short while. Although a good crimp was being applied, the bullet seating depth varied. A quick check revealed that the channel in the seating/crimping die through which the seating stem fits was too narrow in diameter. Removing the seating stem and dropping in bullets showed none would enter the stem’s channel. All were caught by the channel’s edge. In fact, the seating stem could be removed and the bullets were still seated by the channel’s edge but not with any sort of consistency. So, back to the Redding seating/crimping die. Finally, good loads were being assembled.

The next step felt like walking out on a limb. In my experience, two fast-burning smokeless propellants that have consistent precision and easy ignition are W-231 and Titegroup. No 41LC data exists for either. SO READ AND HEED THIS. DO NOT USE THE FOLLOWING INFORMATION IN ANY REVOLVER EXCEPT POST-1900 COLT SAAs AND MODERN REPLICAS THEREOF.

Colt SAA 41 Long Colt chambers have much thicker walls than those for bigger rounds such as 45 Colt, 44-40 and 38-40, so I felt safe doing some careful load development with the two above-mentioned powders.

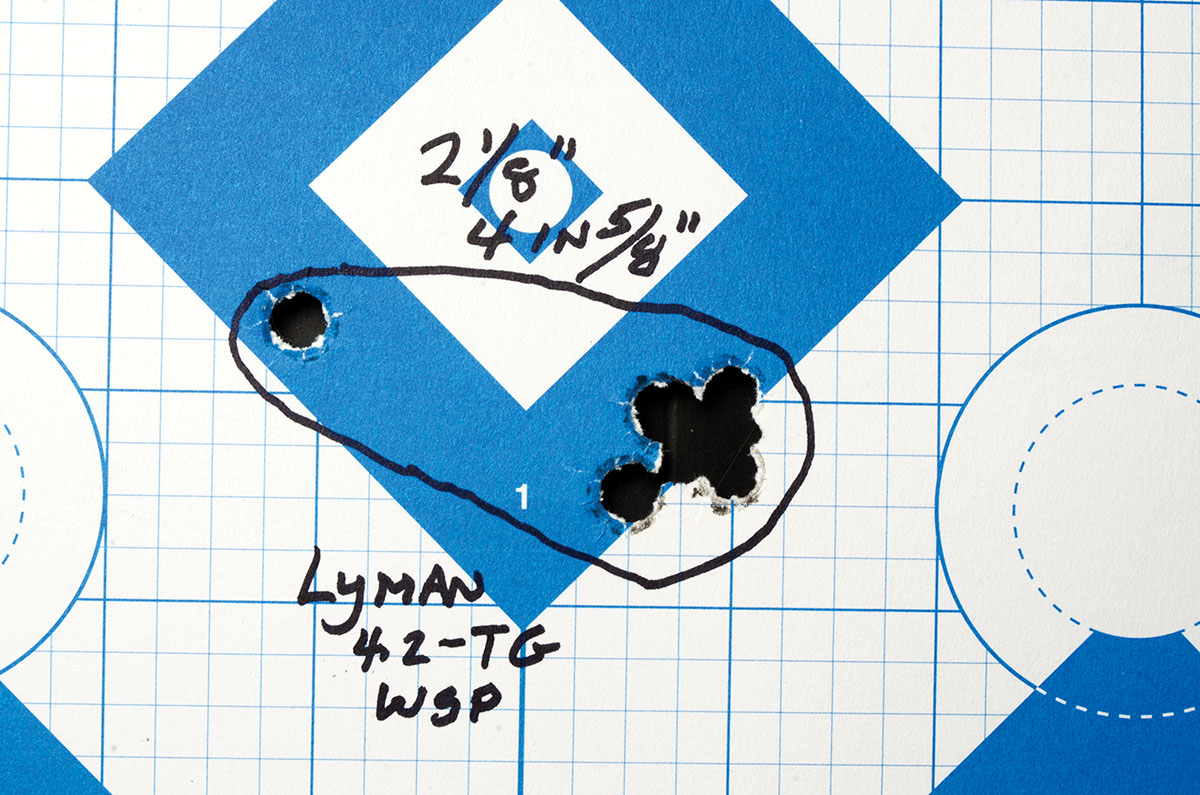

On a whim, some Small Rifle primers were tried. Only Remington’s No. 7½ Small Rifle were on my bench at the time. What a difference they made! Velocities jumped more than 100 fps. Just out of curiosity, I experimented by reducing the 4.2 grains of Titegroup four-tenths of a grain at a time. At 3.4 grains with the Small Rifle primers, chronograph readings were back in the low 700 fps level. In my small lot of shooting with Small Rifle primers, it seemed that on average, groups were tighter and flyers were fewer with all three bullets. The idea deserves more experimentation. Also, on average groups with the MP Mold’s 192-grain HBs were slightly better, which is nice because the double-cavity bullet mould makes production faster.

Many more rounds were fired in this Colt SAA 41 Long Colt than the accompanying table would indicate. In fact, hundreds were fired along the way. The table’s results are what I got for groups and velocities when those particular loads were all fired on the same day. In some ways, this project was frustrating, not to mention expensive. Still, it was satisfying.

.jpg)