The Legendary 220

Swift in Name, Swift in Performance

feature By: Terry Wieland | August, 24

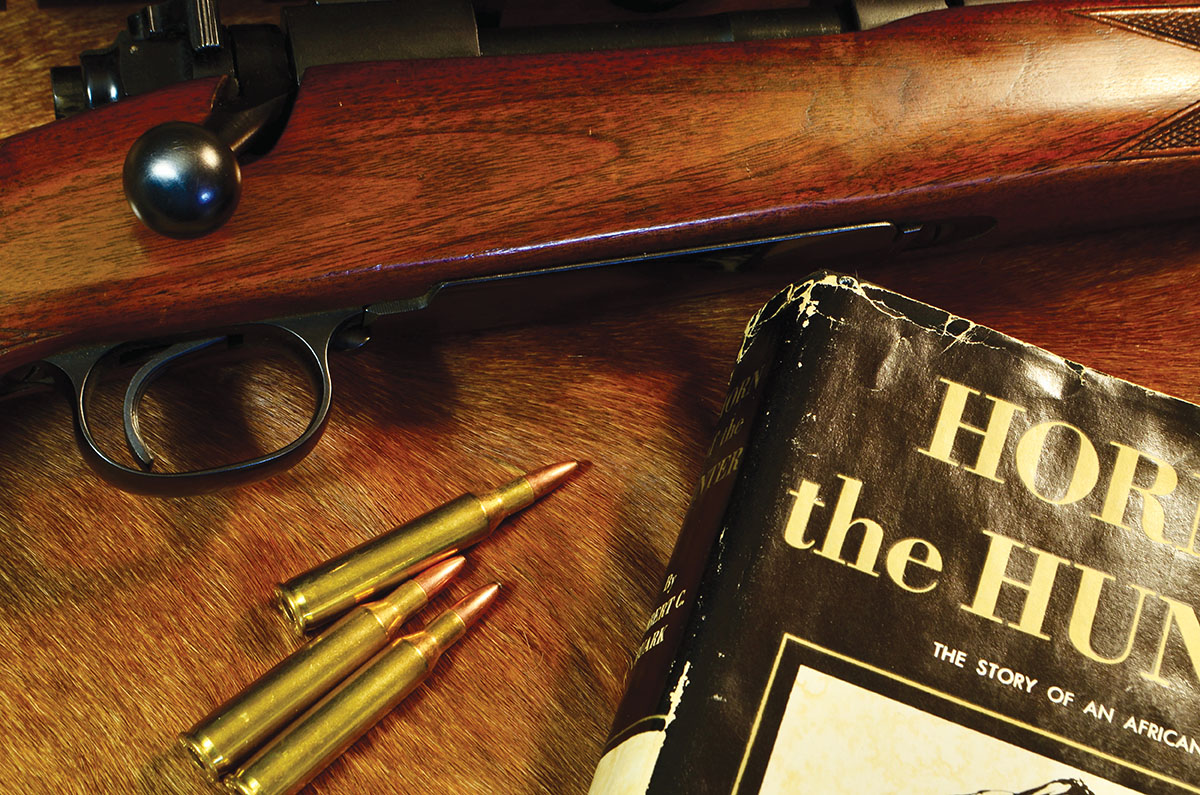

In 1953, the 220 Swift achieved something few other cartridges in history have done – it became notorious nationwide, even among those who knew little about rifles, because it was denounced, by name, in detail, by a famous author in a national best-seller.

The author was Robert Ruark, and the best-seller was Horn of the Hunter, the story of his first African safari that took place two years earlier. In it, Ruark told of his experience shooting first a warthog and then a hyena with his 220 Swift. He wrote that he shot the hyena nine times, inflicting only horrifying surface wounds and, finally, in disgust, finishing it off with a 470 Nitro Express (NE). Ruark then told his professional hunter, Harry Selby, to “throw it away” – saying he would never again shoot any animal he respected with the Swift.

Ruark’s 1951 safari was the realization of a lifelong dream. Having returned from the war, where he served as a naval officer, he resumed his newspaper career, made it big writing a syndicated column, and he amassed the necessary $10,000 for a safari to rival Ernest Hemingway’s 30 years earlier. Although he was a fine shotgunner, he knew little about rifles, sought advice on what to take and someone, somewhere, persuaded him to get a 220 Swift.

Even by 1953, less than 20 years after its introduction, the 220 Swift was fighting an uphill battle. It was a combination of professional jealousy and bad press resulting mostly from some questionable gunsmithing decisions.

Jim Carmichel, former shooting editor of Outdoor Life, is a big Swift fan and in his 1975 book, The Modern Rifle, he traced all the factors that led to Winchester discontinuing the Swift in the early 1960s. They went all the way back to their beginnings.

In the 1930s, word got out that Winchester was planning a super-velocity .22 varmint cartridge. Several well-known wildcatters had been working on just such a project and had come up with the 250-3000 necked down. We now know it as the 22-250 Remington, and they expected Winchester would adopt their design, make it a factory round, and fame (if not fortune) would follow.

The second had to do with metallurgy. Existing barrel steels were not adequate to deal with the Swift’s unheard of 4,000-plus feet per second (fps) velocities and barrels suffered. Worse, gunsmiths and their clients, dazzled by the prospect of a bullet traveling at 4,110 fps, figured they could rechamber existing 22 Hornets and even 22 Long Rifle barrels to the Swift. Naturally, those mild steel barrels deteriorated in short order.

After 1945, Winchester began using more corrosion-resistant alloys, which solved the problem for factory rifles but did nothing for existing custom rifles, and the complaints continued, shaping a reputation the 220 Swift has never shaken off.

Just last year, I was discussing new chamberings with the German maker of some very high-end rifles, I suggested the Swift. His response: “But doesn’t it burn out barrels?”

A related problem was cuprous fouling. The Swift’s super-fast bullet fouled bores super-quickly, and in the 1950s, not much was known about how to deal with it. Accuracy deteriorated and was usually attributed to a “shot-out” barrel. Carmichel noted that every Swift that came his way with a supposedly bad barrel, with only one exception, was returned to fine accuracy with a thorough cleaning.

In fact, he had a point. It was taken out of context, of course, but earlier, stalking the warthog, Selby advised Ruark to shoot the animal in the behind, figuring that if the bullet did not break the spine, it would range up into the chest cavity. Now, a warthog is a tough animal weighing up to 300 pounds or more. Expecting the Swift’s hyper-velocity 48-grain bullet with its paper-thin jacket to perform like that was absurd. Instead, the bullet “peeled a ham off its hip,” the warthog escaped into the brush and was never found.

Ruark was mortified. Then came the notorious hyena.

It’s impossible to say, now, if Ruark’s story was a factor in a number of states outlawing .22-caliber cartridges for deer hunting, but it certainly cannot have helped and there’s no doubt it added to the Swift’s woes.

In 1961, Winchester discontinued the factory Model 70 Swift, moving it to the custom shop and then, two years later, they dropped it entirely. As a final note, in 1965, Winchester introduced a replacement – the 225 Winchester, a rimmed number that closely resembled the 219 Zipper Improved. It was a decent cartridge but a resounding commercial flop. All of this happened around the time of Winchester’s infamous redesign of the Model 70 to produce the post-’64 rifles.

Meanwhile, news of the Swift being discontinued caused a run on the excellent pre-’64 Model 70 Swifts with 26-inch barrels, and many went into collections to sit there, pristine and largely unfired. These reappear in places like Rock Island Auction and generally bring around $2,500. A year ago, six such rifles appeared in one auction, possibly from the same collection – a golden opportunity for anyone who loves rifles and admires the Swift and, there seem to be more than a few such guys around.

Some had 26-inch barrels while others had 24-inch barrels and rifling twists varied, with very early Swifts at 1:16, later 1:14; now, apparently, 1:12 is favored, especially for those wanting to use long, heavy-for-caliber bullets for long-range shooting.

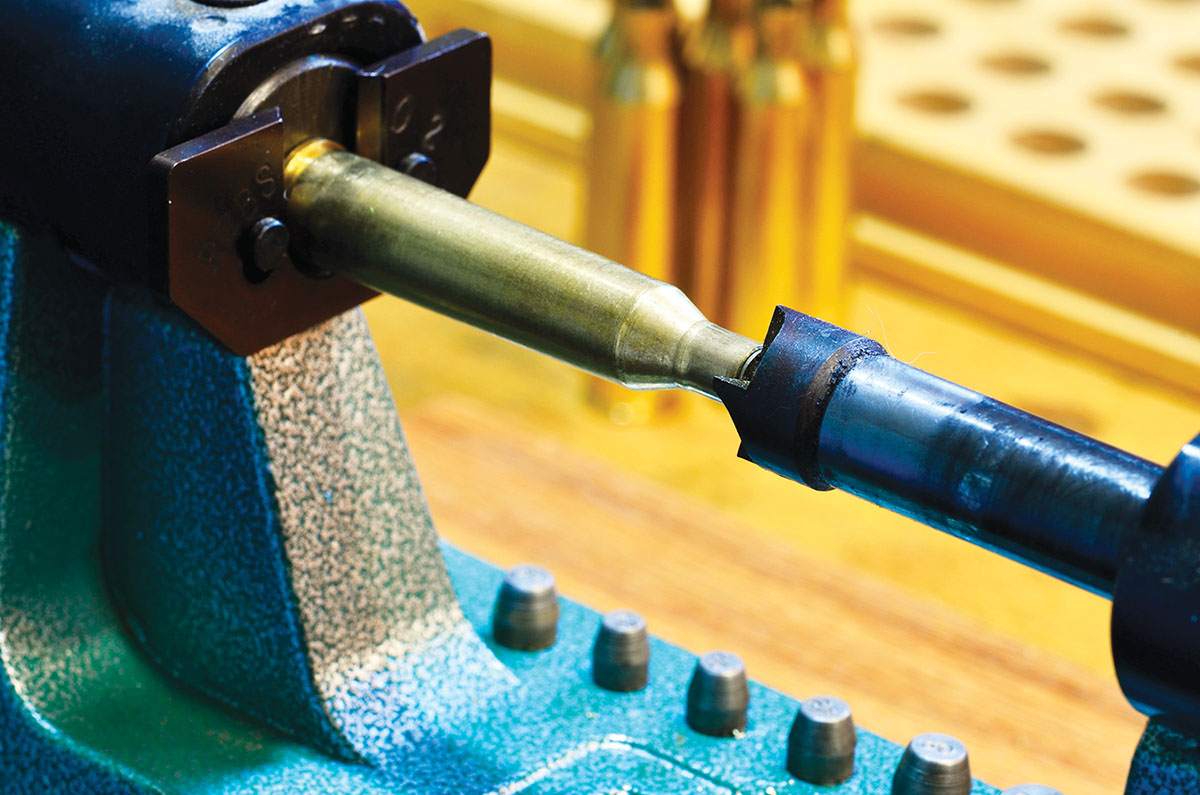

This adds to the hodgepodge of problems facing any 220 Swift owner who wants to develop optimum loads.

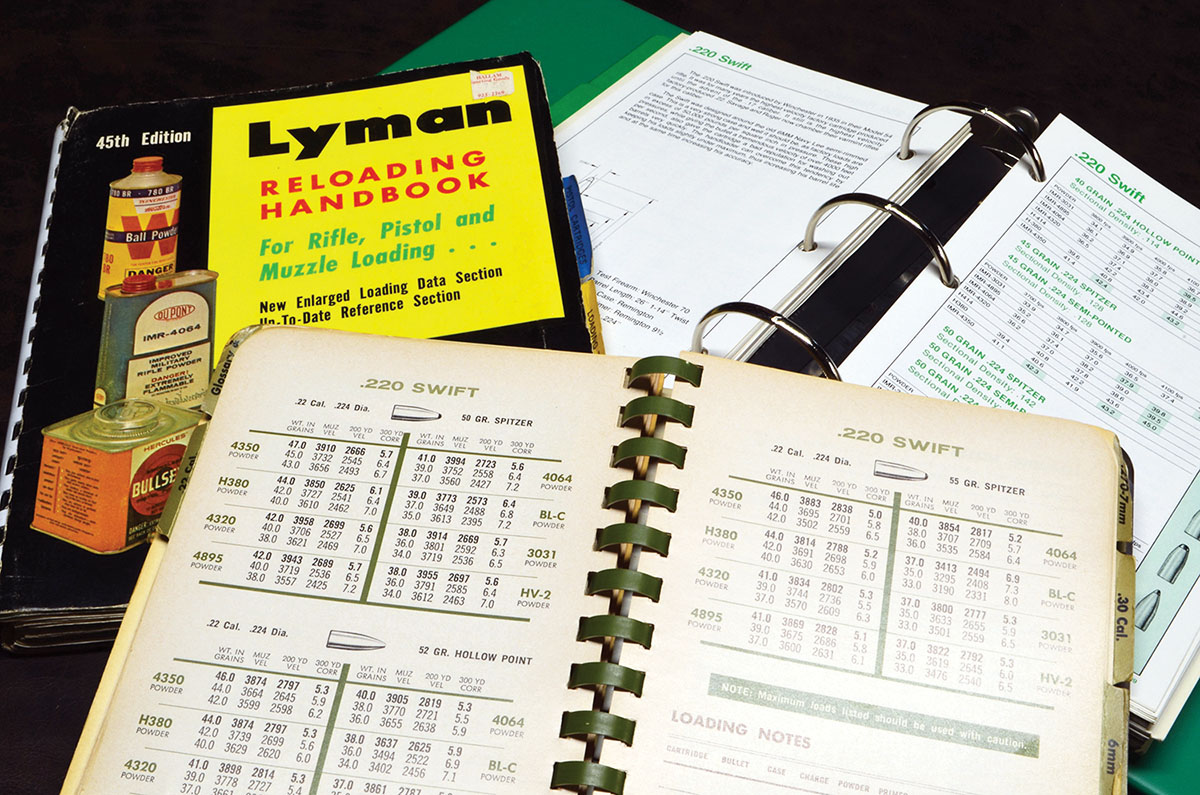

Ken Waters, author of the “Pet Loads” series in Handloader from the 1960s on, covered the Swift twice – September 1978 and June 2000. Both articles are included in the massive anthology Pet Loads (Wolfe Publishing, 2021) and no Swiftie should be without it. Waters examines (and debunks) most of the other complaints about the Swift, such as it having an inordinate sensitivity to slight changes in powder charge, or not being amenable to lighter loads.

Not surprisingly, there is a wide range of handloading data for the 220 Swift, but this can present problems. Some of it calls for powders that are no longer available or it was compiled using anything from custom-barreled surplus Mausers to modern pressure barrels, so where do you start? Finally, there is not much material for new powders because those who compile loading manuals have little interest in making the investment necessary to produce data for an obsolescent cartridge.

For example, in 1978, Waters reported excellent results with H-205, but that’s long gone. In 2000, it was XMR-2495, now known as Accurate 2495, but Hodgdon provides no data for that powder with the Swift.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that the overall best Swift powder, historically, is IMR-4064. Ron Reiber, long-time Hodgdon chief ballistician, told me the other great one is Varget, which is essentially the 4064 equivalent in Hodgdon’s “Extreme” series. Fortunately, there is no indication either of those excellent powders are going anywhere.

Even with good ol’ 4064, there are variations in maximum loads depending on the year of the manual, the test rifle employed, and barrel length. Hodgdon’s current maximum recommendation is 38.4 grains, delivering 3,905 fps with a 50-grain bullet from its 24-inch test barrel.

Older manuals, using rifles with longer barrels and possibly roomier chambers, allow heavier charges. Sierra Bullets Reloading Manual Second Edition (1985) uses a Model 70 with a 26-inch barrel, allows up to 40.2 grains, and records 4,100 fps; in Sierra the Bulletsmiths Edition V (2003) the test rifle is a Savage Model 112VSS, with a 26-inch barrel and the maximum load is 39.9 grains for a velocity of 4,000 fps.

Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition Number 7 (1966), using a Mauser custom rifle with a 25-inch barrel, gave a maximum load of 41 grains of 4064 with a 50-grain bullet and velocity of 3,994 fps.

Originally, I intended to try some of today’s heavy-for-caliber bullets – 70-90 grains – but with a 1:14 twist, it was hopeless. No one makes a 48-grain bullet, so I stuck with 50 grains, which is where the Swift really made its reputation.

The accompanying table tells an interesting story.

While 4064 delivered all the velocity one might want, reaching Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition Number 7 maximum, accuracy fell off as velocity increased.

Ron Reiber’s second recommended powder, Varget, at a maximum load (Hodgdon data) was shy on velocity but okay on accuracy.

The load with H-4895 came from Jim Carmichel’s book, was well short of published maximums, and not only delivered a lovely sub-1-inch, five-shot group as promised, but did so with almost no recoil.

The conclusion here is that every rifle is an individual and needs to be approached as such. The fact that one published load resulted in frightening pressures (Accurate 2700) while other maximums seemed very mild, like Hodgdon’s current maximum with IMR-4064 is 2.6 grains less than Speer’s (1966) recommendation, which strongly indicates one should not make presumptions and always err on the side of caution.

The question now is, does the 220 Swift have a future outside of the odd anachronistic romantic and those who just like to swim against the tide?

Much as it pains me, I don’t think so. I don’t see makers of modern rifles rushing to chamber it, given the number of newer cartridges available, such as the 224 Valkyrie on the small side and the 22 Creedmoor on the large.

But, for those of us who like playing with quality rifles from years past, there is not only the hallowed pre-’64 Winchester but also the Ruger 77 and Savage 112V. If you stick with the Swift’s strengths (velocity and accuracy with lighter bullets) and don’t try to turn it into something it’s not (a long-range big-game rifle) then shooting one is a revelation.

Just don’t take one to Africa. Please.

.jpg)