The heyday of wildcats began a few years after World War II (1945 BC – Before Chronographs, or at least affordable ones). There then existed a pent-up demand for sporting arms, quickly fed by “The Golden Age of Military Surplus.” America was one of the few countries in the world whose citizens had the unfettered right to own as many rifles as they wished. Literally boatloads of obsolete, discarded, abandoned or captured bolt-action and single-shot military rifles came to the U.S. from countries who needed the money for post-war reconstruction. Rifles in really bad shape were disassembled for just the action, which led to an interesting situation.

Though it had been done earlier to some extent, the availability of just the action only induced countless individuals to assemble completely “new” rifles. Of course, these could be chambered for any cartridge that would fit into the magazine, but there weren’t that many factory cartridges at the time. Shooters wanted more velocity (of course), or just something different, or more modern, or all three. Two gunsmiths of the time began addressing this demand.

A classic pre-’64 Winchester M70 custom rifle that has been rebarreled to 280 Ackley Improved – probably in the 1970s.

One of these was Manollis Aamoen (Rocky) Gibbs. In 1954, he began chambering rifles for his series of wildcat cartridges in eight calibers. All were on 30-06 cases blown out to minimum body taper (.015 inch) while the shoulder was moved forward to give a neck length of .250 inch and a shoulder angle sharpened to 35 degrees. Gibbs believed this gave the 30-06 case its maximum possible powder capacity. While offering improved ballistics, their popularity was limited by the need for complex case forming.

Arrows point to the neck/shoulder junction of the 280 Remington (left) and the original 280 AI (right). The length to the base on both rounds is the same, but it has been shortened on the Nosler 280 AI.

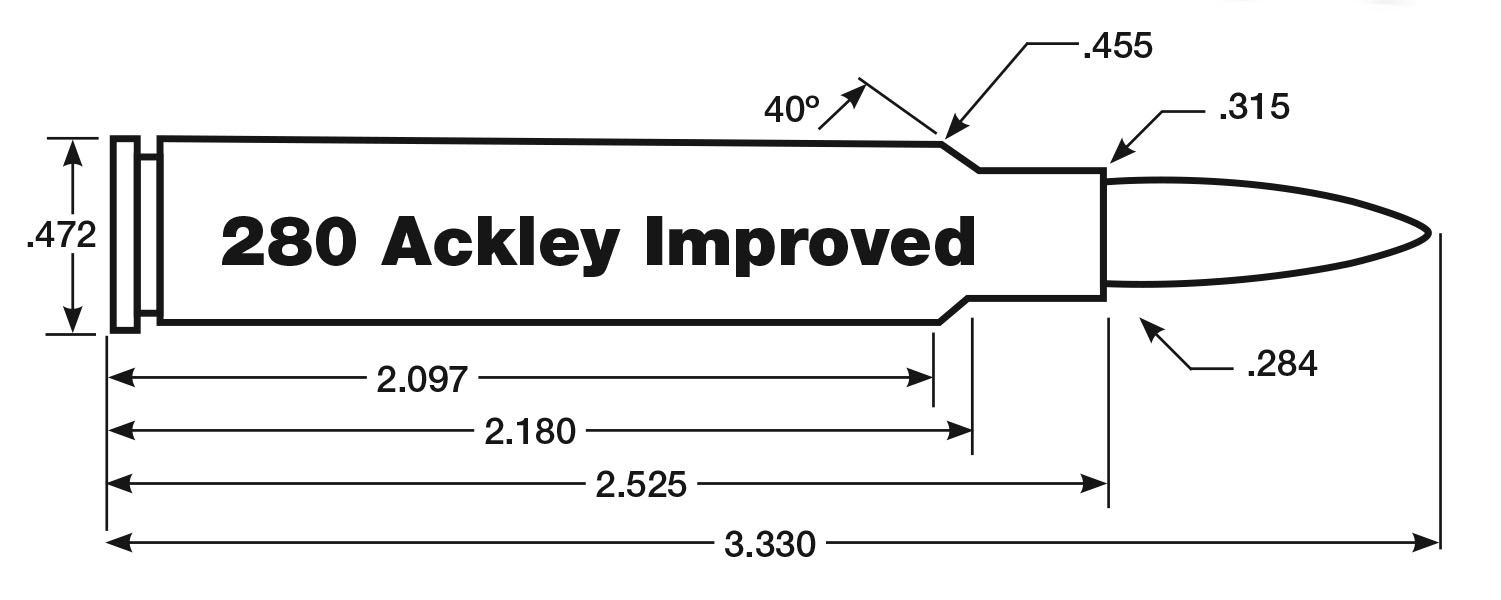

The second gunsmith was Parker O. Ackley, who began work in 1936. A tireless experimenter, he was credited with many (some have said more than 100) wildcat rounds. Ackley’s most famous idea was blowing any case out to minimum body taper, then sharpening the shoulder angle to 40 degrees, pivoting the new shoulder on the existing shoulder/neck junction. This allowed factory cartridges to still headspace properly and form to fit the new chamber simply by pulling the trigger. Ackley referred to these cartridges as improved designs.

Of interest to us here is a cartridge now known as the 280 Ackley Improved, even though P.O. Ackley had little to do with it. The chronicles tell us the 280 Remington was introduced in 1957, chambered in Remington’s Model 742 autoloader and Model 760 pump. Though intended to compete with the 270 Winchester, the new round was put in the autoloader because Remington was convinced autos were the hunting rifles of the future. Unfortunately, the reliable functioning of the Model 742 required limiting performance of the .280 cartridge.

The Ackley Improved form blows the forward portion of all cases out to about .455 inch and sharpens the shoulder to 40 degrees.

At any rate, it is written that quite quickly, Fred Huntington reformed the 280 Remington case to an Ackley Improved shape, but used a Gibbs 35-degree shoulder. There is some disagreement about the title, though it was probably 280 RCBS Improved. Several years earlier, Ackley had produced a 7mm-06 Improved, but dropped it for the RCBS round, with the shoulder angle changed to 40 degrees. This is almost, but not quite, the cartridge we are today calling the 280 Ackley Improved (280 AI).

Ackley’s 280 AI has always been very popular in high-dollar custom rifles. Its straight sides and sharp shoulder give it a modern look that is irresistible to most riflefolk. The powder capacity is increased by some 1.5 to 4 grains depending upon powder kernel size and shape. Velocity could increase 100 feet per second (fps) with powders then available. Unfortunately, it was quite common for handloaders to just keep pouring in various powders until a 200-300 fps gain was estimated, then complain about poor quality cases because primers fell out after two firings! Thus, the 280 AI remained in that wildcat never-never land of either praise or condemnation and severely diminished used gun values.

Redding loading dies for the original 280 AI are labeled 280 Remington Imp. 40º while the dies for the Nosler cartridge read 280 Ackley Improved.

Then, the folks at Nosler began offering empty cartridge cases in 2004. Ammunition for standard rounds and hard to find numbers like 222 Remington Magnum followed. The announcement of the 280 AI came in 2008, however, not as a wildcat, but as a legitimate factory round.

As previously explained, all of Ackley’s improved cartridges maintain the parent rounds headspace. This was the 280 AI Nosler brought to the Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) for approval and standardization. Somewhere along the line, however, the 280 Remington/280 AI base to shoulder/neck junction was shortened .014 inch by SAAMI. Forming the Nosler 280 AI by firing factory 280 Remingtons in the new chamber now appears impossible. Nevertheless, Nosler assures me it can be done, it’s just an interference fit (it means you have to force it). In reality, there is no need since Nosler sells both cases and ammunition. Besides, factory 280 Remingtons for fireforming probably can’t be found today anyway.

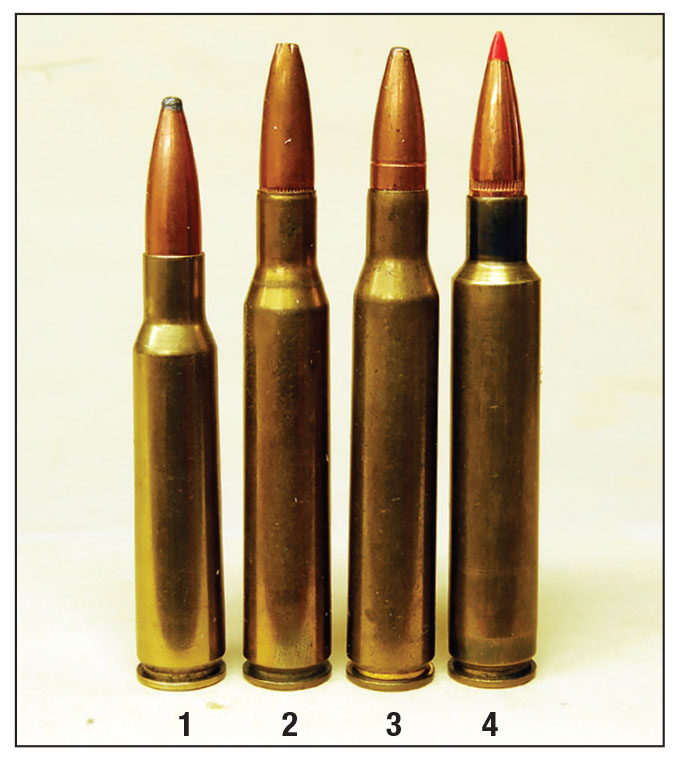

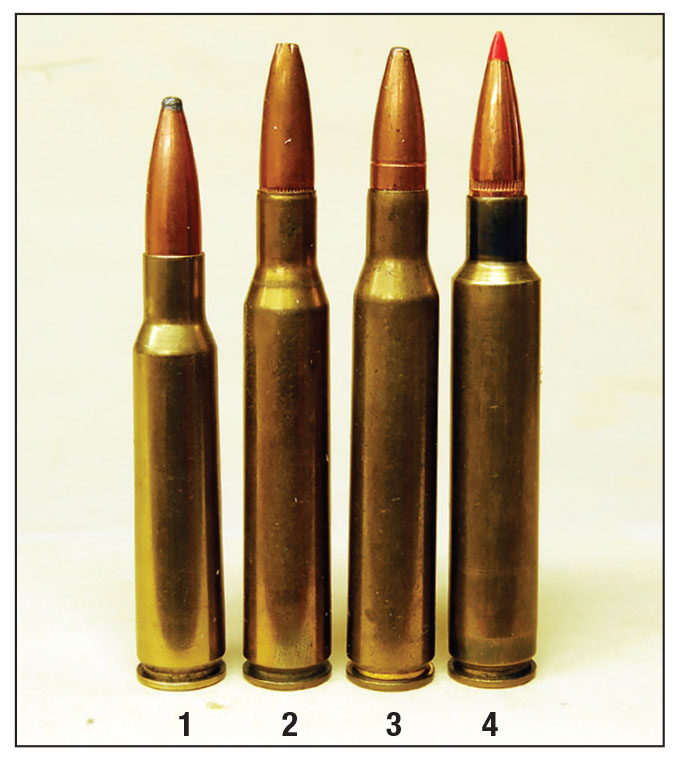

Standard and Ackley Improved cartridges include the: (1) 25-06, (2) 25-06 AI, (3) 280 Remington, (4) 280 AI, (5) 30-06, (6) 30-06 AI, (7) 35 Whelen and (8) 35 Whelen AI.

Even though there is no difference in loading data for the new and old 280 AI, the new round does require its own reloading die set. Redding marks the new dies as “.280 Ackley Imp.” Old Ackley dimensioned dies are .280 Remington Imp. 40º (see photo). Best of all, loading data shot in 24-inch pressure barrels is now commonplace even though the round is probably better in a 26-inch tube. Now, 280 AI owners can meaningfully engage in their favorite pastime of comparing the round to the 7mm Remington Magnum.

Big-game rounds that are often compared include: (1) 7x57mm, (2) 270 Winchester, (3) 280 Remington and (4) 280 AI. The 280 AI provides the most energy but not by much.

Nosler factory ammunition is currently available loaded with the 140-grain AccuBond at 3,200 fps with 140-grain Ballistic Tip at 3,200 fps, 140-grain E-Tip at 3,200 fps, 150-grain AccuBond Long Range at 2,930 fps, 160-grain AccuBond at 2,950 fps and 160-grain Partition achieving 2,950 fps, all muzzle velocities. Some may question factory figures when compared to handloading data, but it must be remembered that most all game bullets today are trick bullets rather than classic cup-and-core construction. They vary in hardness, which affects breech pressure, length, which can influence case capacity and ogive profile, which affects seating depth. It is impossible to even begin to cover all of this.

One facet that can be generalized is sample muzzle velocity. References show the Maximum Average (breech) Pressure (MAP) for the 280 Remington and 280 AI at 60,000 psi, yet, while the former generally shows handloads at around 50,000 psi, the 280 AI is right up to 60,000 psi or slightly above. This is most certainly due to all the Remington autoloaders chambered for the standard round. The MAP for the 7mm Remington Magnum is 61,000 psi, but it is commonly loaded down some 5-10 percent.

In top handloads, the 280 AI will push 140-grain bullets to about 200 fps faster than the 280 Remington but 50 fps slower than the 7mm Remington Magnum. For 160-grain bullets, the 280 AI is about 100 fps over the 280 Remington and 100 fps below the magnum. For the heavy 175-grain bullet, the 280 AI leads the standard 280 by 200 fps and can be nearly equal to the magnum. It all depends on the individual bullet and today’s powders at the slowest burning end of the scale. None of them were available when the three rounds appeared – or for 30 years thereafter!

The 280 AI holds five rounds in the magazine compared to four for the 7mm Remington Magnum – if this is important.

The 280 AI was a reasonably popular wildcat and would have been a more popular factory number had it not been for all the hullabaloo generated by the “6.5 Whatevers.” Certainly, owners of old Ackley-dimensioned rifles can be thankful for the pressure tested loading data that applies equally to their rifles.

.jpg)