.44-40 Winchester Loads

Feeding Classic Sixguns

feature By: Brian Pearce | December, 21

In an effort to improve upon the power, accuracy and versatility of the .44 Henry Rimfire cartridge chambered in the 1860 Henry and 1866 Winchester rifles, Winchester developed the .44 Winchester (later known as .44 W.C.F., .44-40 and .44 Largo by Spanish countries) cartridge by 1873, which was that firm’s first commercial centerfire cartridge. It was the standard chambering for the Model 1873 rifle, which was a combination that became popular across the U.S., but would become most famous as “The Gun That Won the West.” It became a favorite of many notable cowboys, frontiersmen, lawmen, hunters, showmen, kings and presidents. In an effort to avoid using the Winchester name, when the Union Metallic Cartridge Company began offering ammunition, it labeled it as the “.44-40,” with the “44” referencing its caliber (although it was technically a sub-.43 caliber) and the “40” indicating the charge weight of black powder. That name stuck and Winchester eventually began labeling ammunition as .44-40. Early ballistics listed a 200-grain lead bullet at 1,245 feet per second (fps), but by 1875, stated velocity was bumped to 1,300 fps. While these ballistics are not particularly impressive by today’s standards, the old “forty four” has accounted for countless deer, grizzly, moose, bison and became known as a formidable man-stopper.

To further escalate the .44-40’s popularity, Colt, Smith & Wesson, Remington and others soon began offering excellent .44-40 sixguns, making it the first successful cartridge chambered for both rifles and sixguns. The option to have a rifle and sixgun of the same caliber was highly practical, especially on the frontier, where ammunition availability was sporadic at best. Black-powder ballistics were primarily listed for rifles; however, in long barreled sixguns, such as the Colt SAA with a 7½-inch barrel length, the load would reach around 1,000 fps.

By 1895, Winchester began offering smokeless powder loads (DuPont No. 2 smokeless powder) at the same velocities. However, “lead metal patched” (or what we know today as a jacketed softpoint) bullets began appearing in quantity around 1900. With more modern and stronger rifles being offered, such as the Winchester 1892 and Marlin 1894, Winchester began offering “High Velocity” or “WHV” loads that pushed 200-grain metal patched bullets to 1,540 fps; however, it was specified that these loads were not to be used in revolvers or Winchester 1873 rifles. During the pre-World War II years, the .44-40 was loaded with bullets weighing 115, 122, 140, 160, 165, 166, 180, 200 and 217 grains, as well as blanks, shot and other specialty cartridges.

Modern cowboy action loads containing cast bullets have been offered with 160-, 180-, 200-, 205- and 225-grain weights and with velocities usually between 700 and 850 fps. Winchester’s traditional jacketed softpoint (JSP) load has been standardized with the 200-grain Power-Point bullet at 1,190 fps, which is suitable for any firearm in good working condition and designed specifically to fire smokeless powder ammunition. It should be noted that into the 1970s, this same bullet was listed at 1,310 fps from a rifle and 975 fps from revolvers, but is now omitted regarding velocities from a revolver. Just for fun, samples of the Winchester 200-grain JSP loads from my ammunition collection that were manufactured in the 1930s, 1940s, 1960s, 1970s and 2000s were checked for velocity from a Colt Frontier Six Shooter with a 7½-inch barrel. They recorded 992, 1,011, 964, 961 and 810 fps, respectively.

Growing up in Idaho and Oregon ranch country, it was noticed that many of the old cowboys and ranchers still used the .44-40 in a variety of guns. However, when a retired shirttail relative from Arizona came to visit our remote ranch for a week and brought along a historically significant Colt Frontier Six Shooter with a 4¾-inch barrel, nickel-plated with ox-head carved pearl stocks and plenty of ammunition, my real experience with the cartridge began. In spite of more than 60 years separating us, we became good friends. I would take him around the ranch and bagged a lot of small game and pests with that old sixgun. In the years since, I have owned many .44-40 rifles and sixguns and have greatly enjoyed the historical perspective of this unique cartridge, but have also used it to take deer cleanly with a single shot, in spite of critics claiming that it is too puny.

With the better designed and more powerful .44 Special and .44 Magnum cartridges growing in popularity and offered in modern guns, it seemed as though the .44-40 was doomed to obsolescence. However, for several reasons that has not occurred. First, there has historically been tremendous interest in early modern firearms and their historical role. Long before the popular sport of cowboy action shooting, firearm companies such as Uberti and others began offering reproductions of various Winchester pattern rifles and Colt and Remington revolvers. Interest by shooters was already firmly established when the sport of cowboy action was organized. While the popularity of that competition has waned somewhat in recent years, there remains steady interest in early modern firearms and their cartridges such as the .44-40, and most shooters that choose this cartridge handload for it.

Today, the .44-40 has a Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute (SAAMI) maximum average pressure of 13,000 CUP, which is the pressure level that I personally prefer to hold handloads to. The .44-40 case is thin and cannot handle as much pressure as other modern .44s, such as the .44 Special or .44 Magnum. In addition to the case not offering as much bullet pull to obtain proper powder ignition and prevent bullets from jumping crimp, heavy or high-pressure loads will significantly shorten case life and can even result in case separation. Furthermore, due to its bottleneck configuration, revolver chamber walls are thinner, which is another reason to keep pressure levels within reason. The accompanying data is within industry pressure guidelines.

Like so many cartridges that originated during the black-powder era, the .44-40 can have significant differences in throat and barrel groove dimensions. For example, Colt first began offering the SAA chambered in .44-40 around 1878. Guns produced prior to 1900 (or with a serial number below 192,000) are black-powder guns and should not be used with smokeless loads. These sixguns feature small, bead-style rifling, while groove diameter was generally a tight .424 inch; however, I have one gun that measures .423 inch. Throats typically measure .423 to .424 inch. Sometime around 1908, Colt changed its rifling to a flat style (the same as it uses today), but at the same time, the specifications were changed with a minimum groove diameter of .426 and maximum of .427 inch. The bore was .419 minimum and .420 maximum, while throats were .428 inch. Incidentally, when Colt first offered sixguns chambered in .44 Special in 1909, it used .44-40 barrels, but naturally with a different roll mark. Moving forward to third-generation Colt SAA and New Frontier .44-40s, they will generally share the above dimensions, which is conducive to an accurate sixgun.

Most other .44-40 sixguns, including the Remington Models 1875 and 1890, Smith & Wesson New Model No. 3 Frontier, .44 Double Action Frontier, etc., were black-powder-era guns and really don’t fit within this subject of smokeless handloads. However, Smith & Wesson made a few .44 Hand Ejector First Model New Century (aka Triple Lock), .44 Hand Ejector Second Model, .44 Hand Ejector Third Model and commemoratives in .44-40, which generally had a groove diameter of .430 inch.

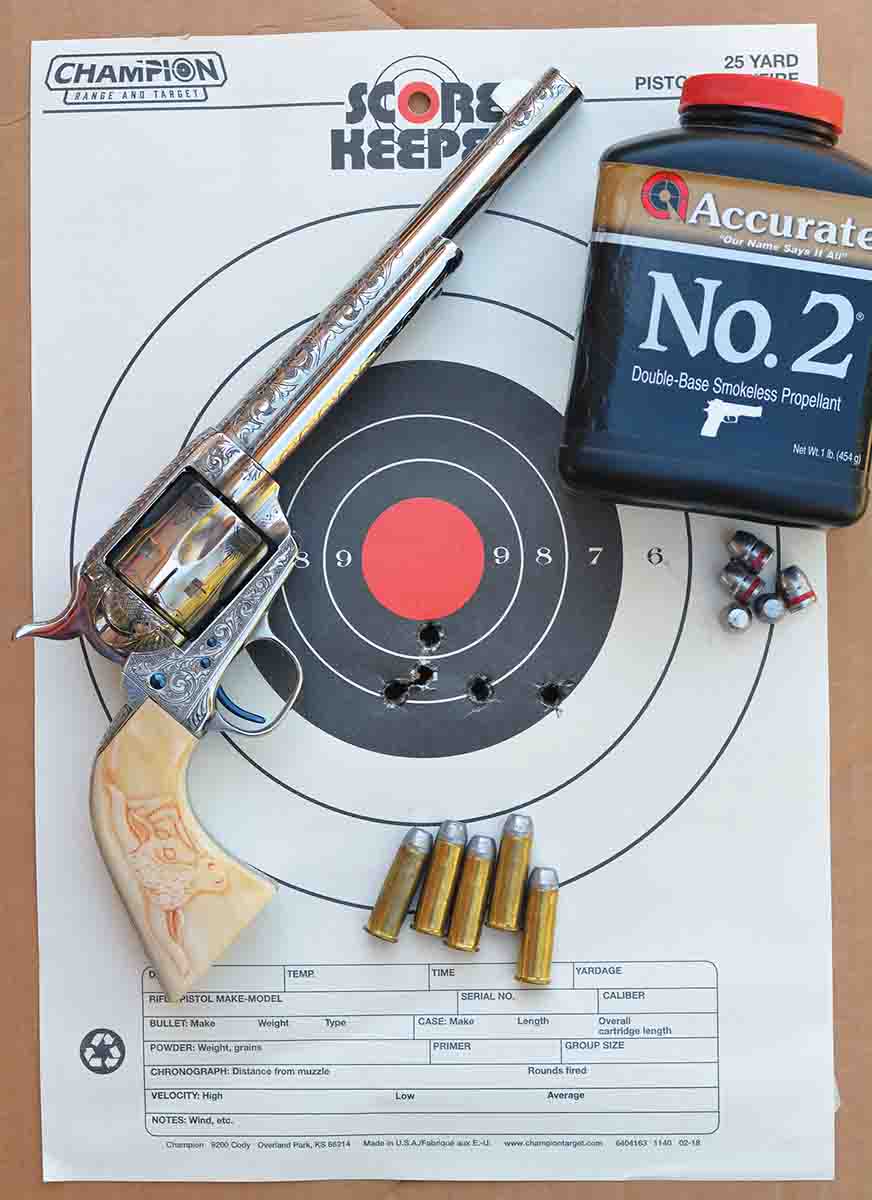

To develop data for the .44-40, I selected a Colt SAA “Colt Frontier Six Shooter” from my own collection that was manufactured in 1881, but was fully rebuilt internally and received proper roll-marks externally. However, it now sports a smokeless cylinder and barrel to allow me to shoot any reasonable load with modern components. It features a 7½-inch barrel, which was popular during the 1870s through the 1890s and was the original length for this particular sixgun. Before the nickel-plating was applied, I had a Cuno Helfrict pattern engraving applied (one of Colt’s premier period engravers on the SAA). Finally, a set of one-piece steer head carved stocks were fitted. This custom sixgun features .428-inch throats and a .427-inch groove diameter and has proven capable of outstanding accuracy.

It is noteworthy that the Colt Frontier Six Shooter was the designated name for Colt Single Action Army revolvers chambered in .44 WCF, or .44-40. This was the second most popular caliber in the SAA, being second only to the .45 Colt. While it certainly gained some of its popularity because of rifles of the same caliber, such as lever guns offered by Winchester and Marlin, it was still a good enough cartridge to gain popularity based on its own merits.

To develop .44-40 handload data, Starline cases (available factory direct at 800-280-6660) were used exclusively, which due to their design and strength are a significant help in making better handloads and are much more forgiving for handloaders to work with. Historically, Winchester and Remington cases feature a cannelure near the base of the bullet to prevent it from deep-seating in tubular magazines. The cannelure often causes cases to split prematurely, which limits case life, but they also create a fault line for cases to stretch unevenly. To obtain a uniform roll crimp, cases need to be uniform. Due to the thin design of the case, especially older cases, over crimping is certain to cause the case to deform, which is often just below the crimp or at the shoulder, and results in an out-of-spec cartridge that will not chamber. Again, Starline cases are stronger, void of a cannelure, uniform in length and can be reloaded many more times than traditional cases. Due to increased strength, they offer an improved bullet pull that results in more uniform ignition and often better accuracy. Incidentally, balloonhead cases were discontinued around World War II and should not be used; rather they should be relinquished as collector’s items.

.jpg)

Cases should always be full-length sized. If they have been fired in multiple guns, be certain that the sizing die will bring the case back to industry specifications. Some sizing dies, especially older versions, have been observed that will not size the shoulder properly to allow cases to freely enter into the chambers of all guns. This can be checked using a case or cartridge gauge, or test a sized case to see if it freely enters all chambers. RCBS Cowboy dies were used to develop the accompanying data.

Cases will need lube prior to sizing; however, due to the thin case the quantity applied should be very modest or case denting can occur. Spray on lubes from Hornady, Lyman and RCBS provide plenty of lubrication and will speed up the sizing operation.

Due to the thin case walls, care should be taken to make certain that cases enter true with the expander ball. The expander ball should always be at least .002 inch, or better, .003 inch smaller than bullet diameter. Case mouths should be flared just enough to allow the bullet to begin seating and not catch on the bullet during seating.

Historically, a variety of primers have been used in .44-40 factory loads, including large rifle primers; however, small primers were used in smokeless ammunition around 1900. When using data that is within industry pressure guidelines in conjunction with easy-to-ignite powders, a large pistol (standard) primer is preferred, with CCI 300 used here. They will provide reliable ignition, produce low extreme spreads and are easily ignited, even in revolvers fitted with a reduced power mainspring.

Powders that produce the best general accuracy in sixguns include those that are least position sensitive. The .44-40 is a rather large case and it normally only requires comparatively small charges of powder to reach the maximum average pressure of 13,000 CUP. As such, powder charges can be positioned against the base of the bullet, the primer or laying level and velocity will not change, or show very little change, when matched with correct powder choices. Virtually all powders in the accompanying data performed well; however, a few standout choices include Hodgdon Titegroup, Accurate No. 2, Alliant BE-86, American Select, Power Pistol, Red Dot, Bullseye and Winchester 244.

Period .44-40 jacketed bullets usually measured .426 to .427 inch, and up until a few years ago, these bullets were offered as a component from Winchester and Remington, but have not been offered recently. This leaves jacketed bullets designed for the .44 Special/.44 Magnum that usually measure .429 to .430 inch. These can be readily handloaded for smokeless-era rifles; however, I have owned a number of sixguns that will not allow cartridges loaded with these oversized bullets to chamber properly, owing to the enlarged diameter of the neck. Nonetheless, I have included some data with 200-grain jacketed bullets, but it is suggested to make certain the loaded cartridges will chamber in a given sixgun before loading a large quantity of ammunition.

The .44-40 is always at its best with cast bullets, with several outstanding versions offered commercially, or moulds for the do-it-yourself caster. Generally speaking, properly designed bullets weighing between 200 and 225 grains are the best choices. Heavier bullets have been successfully used; however, they pose certain problems and are not really proper to discuss here. Bullets that are designed for the .44-40 will feature a grease groove that is always contained within the case neck to prevent lube from contaminating the powder charge. They will also feature a proper crimp groove (unless black powder is used to support the base of the bullet) and the nose length will keep overall cartridge lengths within 1.592 inches. Cast bullets should generally be sized .427 to .428 inch.

The 200-grain RNFP Magma design, offered by several cast bullet companies, always shoots surprisingly well when fired from a tightly-chambered sixgun (with Rim Rock Cowboy bullets being used in the accompanying data). The 225-grain Magma RNFP bullet also works well and is used in many factory cowboy loads. An excellent general-purpose bullet comes from RCBS mould 44-200-FN, which casts around 210 grains and features a full-caliber front driving band with a flat base. Accuracy is usually top-notch.

For those that might want to hunt with their .44-40 sixgun, consider using 220- to 225-grain bullets from Lyman/Thompson mould 429215. This SWC features a gas check and was designed for the .44 Special; however, its lube grooves are positioned to keep grease contained within the .44-40’s neck. The overall cartridge length is usually around 1.650 inches, which is longer than SAAMI specifications allow; however, cartridges chamber perfectly in virtually all smokeless-era sixguns, but will not feed in many lever actions. Accuracy is generally excellent.

Cases should be uniform in length with a roll crimp gently applied, preferably as a separate step than when seating the bullet; however this is not necessarily required. If cases vary in length, consider using a Lee Factory Crimp Die, which will produce uniform crimps and proper bullet pull.

The .44-40 is not difficult to handload, however, it does require a bit of finesse. It is an American classic that played an important role in history, but it is also incredibly fun to shoot, is accurate and chambered in a variety of popular guns. In the words of Frank Barnes in Cartridges of the World, “The .44-40 is one of the all-time great American cartridges. It is said that it has killed more game, large and small, and more people, good and bad, than any other commercial cartridge ever developed.” If you don’t already have one, give it a try, you’re in for a treat.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)