In Range

Hollow Victories

column By: Terry Wieland | December, 21

Except for cave paintings, there were no written records way back when. But written records can, themselves, be treacherous – or at least, willfully incomplete, depending on the author’s personal (to say nothing of vested) interests.

There are two monumental, nineteenth-century works on guns, rifles and shooting generally, which are widely quoted and have served as primary references for gun scholars ever since their publication. The first was The Modern Sportsman’s Gun & Rifle, published in two volumes in the 1880s by J.H. Walsh, aka “Stonehenge.” Walsh was editor of the English weekly The Field, and was widely regarded as an expert on things that go “bang” as well as a mind-bogglingly wide range of other subjects on which he wrote books, from dog training to household economy.

Even for the Victorians, who worshipped learning, Walsh was a polymath of breathtaking proportions. He even designed a break-action shotgun – the “Gun of the Future,” which is my candidate as the ugliest shotgun design of all time. As a writer and researcher, however, he was meticulous, painstaking and went to great lengths to be fair and objective. For this reason, it’s a surprise to find any notable omission.

At the other end of the scale, we have William Wellington Greener, a Birmingham gunmaker of undoubted brilliance, but with an ego to match. Aside from building a gunmaking empire and inventing such enduring devices as the Greener crossbolt, still in use after 140 years, Greener wrote several books. His magnum opus was The Gun and its Development (1881), which, as far as I know, is still in print. My copy, a birthday gift in the early 1970s, is a ninth printing (1910). Greener’s major failing as a writer and historian was an almost pathological reluctance to give anyone else credit for an invention, or even for being a fine gunmaker. As a result, there are curious gaps in his information. In describing different bolting systems, for example, he illustrates the Purdey double underlug, operated by a top lever and Scott spindle, but credits neither Purdey nor Scott, both of whom made fortunes from their patents on those devices, and which are still the standard bolting system today. Greener preferred his own crossbolt and was grudging in his acknowledgement of any other.

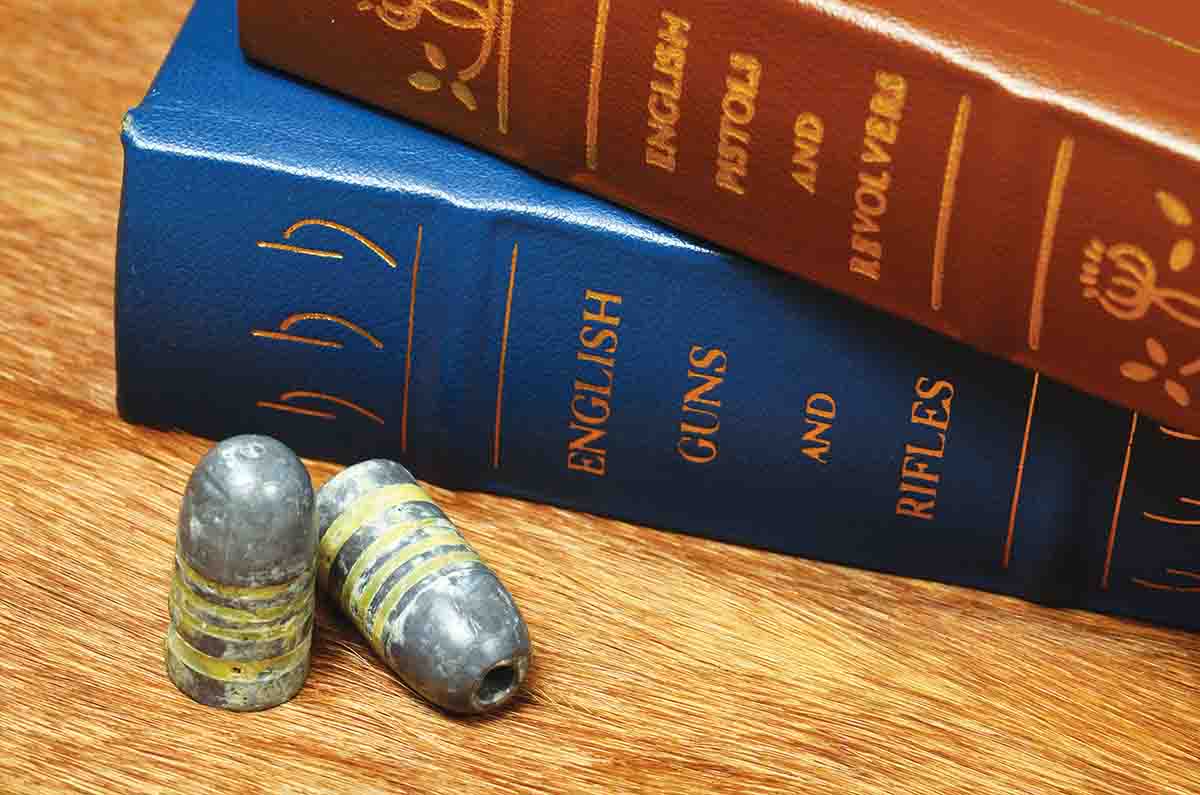

John Nigel George was an English firearms historian of a later era. His two books were both published by Thomas Samworth’s Small-Arms Technical Publishing Company in the U.S. First came English Pistols and Revolvers (1939). It was to be followed by English Guns and Rifles, but this was interrupted by the war. In early 1939, foreseeing the conflict, George joined the Territorial Army. When war broke out, he was sent to France, where he suffered a severe head wound. He was among those rescued at Dunkirk and was later discharged from the army because of his wound. He recovered, however, reenlisted, and was killed by a sniper in 1942 while serving in the Western Desert with the British Eighth Army.

The manuscript, unfinished at his death, was completed by his friend and fellow gun collector, S.B. Haw, who contributed the final chapter on service rifles.

All of this is interesting because of two nuggets of information I came across while reading a borrowed copy of English Guns and Rifles. I was only halfway through it when I resolved to track down and acquire a copy of my own, as well as George’s earlier book on handguns. They are both that good. (Both were reprinted in 1999, bound in leather, as part of a series of classic gun books, which makes them fairly readily available, and usually in “unread” condition.)

The first nugget concerns Charles Lancaster, one of my favorite London gunmakers, and its involvement in the earliest origins of centerfire cartridges.

Most modern firearms histories begin with the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, where Casimir Lefaucheux displayed a break-action gun. This was adopted by Joseph Lang in pinfire form, spelled the end of muzzleloaders and gradually evolved into the “central-fire” cartridge of the 1860s. The next milestone was the great legal dispute in the 1860s between George Daw and Eley Brothers over patent rights to that cartridge.

According to J.N. George, Charles Lancaster designed a workable central-fire rifle cartridge a dozen years earlier than Daw, patenting his invention in 1853. The Lancaster in question was Charles William, son of the famous barrelmaker and founder of the company, who died in 1847. His cartridge had a metal base resembling a modern rimfire. The inside of the base was smeared with fulminate and a perforated disk was pressed down on top. The disk provided the anvil for the striker, kept the fulminate and gunpowder separate, and its perforations allowed the flame to pass through and fire the cartridge. The arrangement of hammer and striker was very similar to later designs. Altogether, it was a remarkable – and very modern – conception of a centerfire cartridge. Lancaster’s design even included a workable extractor system.

George expressed considerable surprise that neither Walsh nor Greener saw fit to even mention this groundbreaking and potentially revolutionary invention. I finally found it in The British Shotgun – Vol. 1850-1870, the first volume of Crudgington and Baker’s three volume work on firearms patents. Surprisingly, it is not mentioned, either in Donald Dallas’s The British Sporting Gun and Rifle – Pursuit of Perfection 1850-1900, which has been my bible on the subject for more than a decade.

The second nugget of information – and here we cast back to fire and the wheel – concerned the question of how the first hollowpoint bullet was contrived. Who? When? Where? The principle of increasing striking power by having the bullet mushroom may be obvious, but it wasn’t in 1820. At that time, the dominant questions were how to fashion a bullet that could grip the rifling and not strip, yet not be so tight that it could be seated with a ramrod. Terminal ballistics were not a major concern.

General John Jacob of the Scinde Irregular Horse experimented with closely-fitted projectiles containing an explosive charge that would explode as they penetrated. General Jacob succeeded in blowing up an ammunition caisson at 2,000 yards. Others followed by trying to adapt his concept to big-game rifles.

One was Captain J. Norton, who experimented with hollowpoint expanding bullets in 1823. The discovery was made when he fired a projectile without its explosive charge inserted, leaving the nose hollow. Later, Lieutenant James Forsyth discovered that a bullet that expanded on impact caused almost as much devastation as one containing an explosive charge. He expounded his discoveries in his book The Sporting Rifle and its Projectiles, which appeared in 1867.

Neither Norton nor Forsyth receives more than passing mention in either Walsh or Greener, and then not in connection with the expanding bullet which, in hunting-rifle terms, ranks as a groundbreaking development. Nor is either mentioned in Donald Dallas’s book – which, admittedly, is more shotgun oriented.

The point is that Walsh and Greener, being chronographically closer to Forsyth’s time, and with his book readily available, should have taken notice of his achievements.

But then, the same could be said of the hairy guy on the edge of the clearing that saw one of his mates start rolling a log, and then pulling it along, and uttering Eureka! or whatever cavemen uttered when they made a discovery. That’s one of the things that makes history so interesting: The work is never, ever finished.