Techniques for Sizing Case Necks

How to Get More Accuracy

feature By: John Barsness | December, 21

Case necks usually affect accuracy far more than weighing every powder charge and bullet, because the neck is the last thing a bullet touches before entering the rifling. Yet many handloaders never bother to measure case necks to make sure they hold bullets the same way for every shot – and when resized in typical dies they sometimes don’t.

I’ve described the reasons before, the last time in “Rifle Die Design” (Handloader No. 321, August-September 2019), but the main points should be repeated. The biggie is the expander “ball” (usually a tapered cylinder) in typical sizing dies, whether full-length or neck-sizing. The neck or entire case is resized by pressing it into the die, and when pulling the case out the sized-down neck passes over the expander ball.

There are two reasons for typical expander ball sizing dies: First, they ensure the inside diameter of the neck is reasonably uniform with any brand or batch of brass. Neck thickness often varies slightly in different brands and manufacturing lots, and even individual cases of the same lot. Consequently, the die must size the neck down more than necessary before being “bumped up” by the expander, usually to about .002 inch smaller than bullet diameter.

Standard expander ball dies are also relatively inexpensive to manufacture. This appeals to most handloaders, especially those who theoretically handload to save money. (Most actually spend more, using the “savings” from handloading to buy more guns and handloading tools.)

However, standard expander ball dies often result in necks being pulled out of line with the case body. The typical shellholder only contacts about half the case’s rim, and the expander ball is normally screwed onto the bottom of the decapping spindle (where it also tightens around the decapping pin). Thus, the case can easily tilt while being pulled over the expander, resulting in a slightly misaligned neck.

Due to the extra effort required to push bullets into such undersized necks, the bullets tend to seat crooked, and the neck’s tension on the bullets can also vary considerably. Neither helps accuracy.

That said, typical sizing dies vary somewhat in interior dimensions. Manufacturers usually use the same reamer as long as interior die dimensions remain within The Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturer’s Institute (SAAMI) limits, so some mass-manufactured dies have slightly smaller or larger neck dimensions.

On rare occasions, a die will correctly “match” the neck thickness of a certain batch of brass closely enough to bypass using the expander ball. In this happy circumstance, the necks not only align closely with the case body, but neck tension is fine as well. However, in the 40-plus years I’ve been using expander ball sizing dies, this has happened twice, with specific .221 Fireball and .300 H&H dies and particular batches of brass.

Some die companies will custom-hone the neck portion of their sizing dies to a specific diameter if a handloader sends them some sample cases, but the cases have to be very consistent in neck thickness. This is accomplished in three ways: sorting for consistent thickness, buying very consistent brass (which usually costs more) and outside neck-turning.

Entire essays have been published just on neck-turning, and despite what some handloaders believe, it often does not make much difference in average factory brass. If the necks vary much in thickness, the case body generally does too. This results in the entire case curving after firing or even resizing, another source of potential inaccuracy.

In some standard dies the expander ball/decapping spindle can be raised high enough to work the same basic way. I have done this a number of times with Hornady, Lyman and RCBS sizing dies, but so far, no Redding dies have allowed the expander to rise high enough.

The downside of this upward adjustment is the decapping pin also rises too high to do its job, so unlike Forster Bench Rest Dies, primer removal requires another step – one reason I am fond of turret presses with a Lee decapping die “permanently” installed in one hole. I have two reloading rooms, a big one in our detached garage, and a smaller one in the basement, for use when the garage is either too hot or cold for comfort – not uncommon in Montana. The primary presses on each bench are turret models with lots of holes, a Lyman All American 8 and a Redding T7.

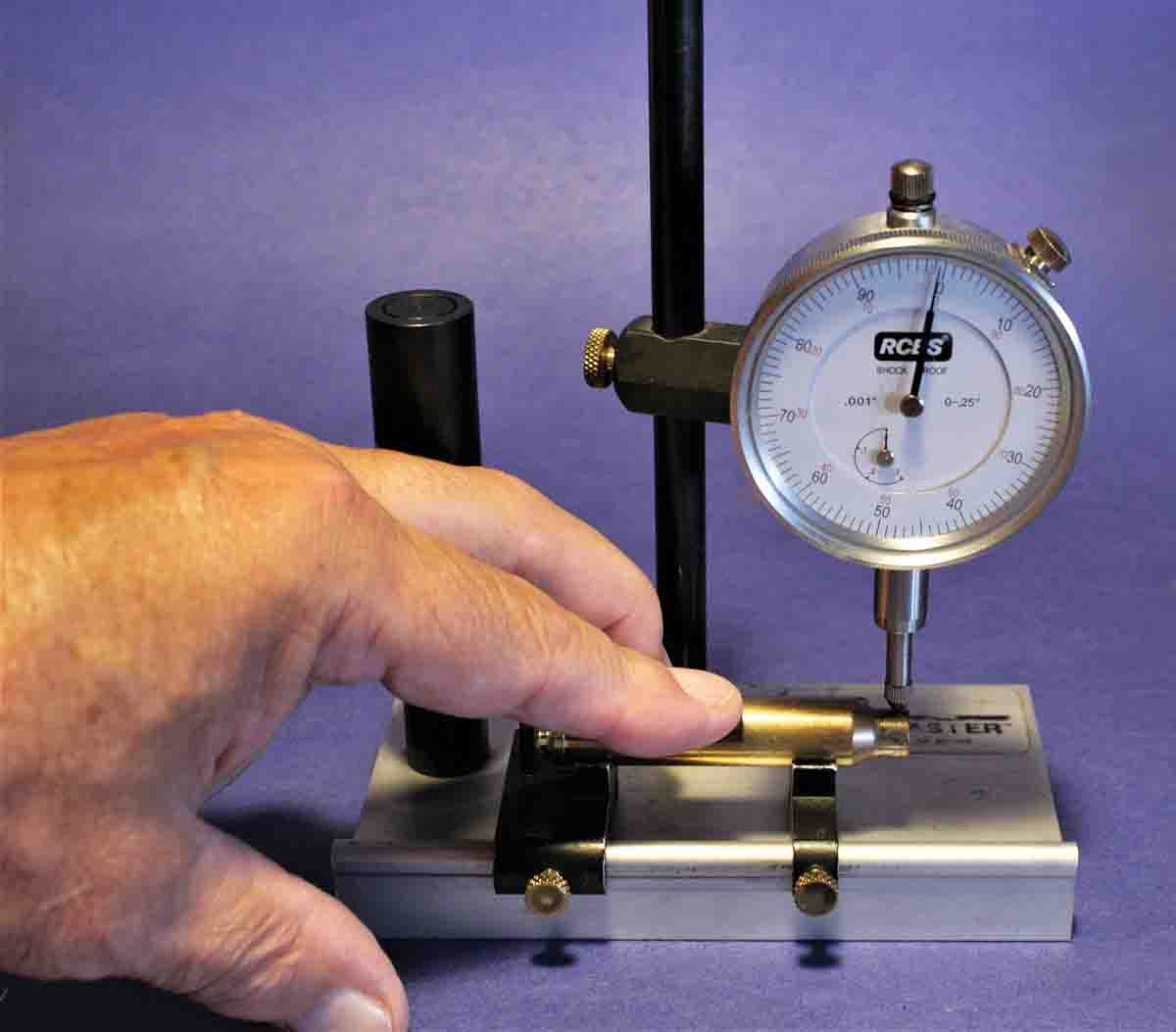

The first thing I do after acquiring a set of standard expander ball dies is run several cases with uniform neck-thickness through the sizing die, then use a concentricity gauge to see if cases come out reasonably straight. For general handloading, necks should vary no more than .002 inch in concentricity when measured just behind the case mouth.

This usually results in runout of seated bullets of no more than .005 inch, measured 0.1 inch ahead of the case mouth. This is so small that rolling a loaded round across a level surface doesn’t show any visible “wobble” in the bullet’s tip, and normally results in all the accuracy a typical factory big-game rifle can produce. Of course, some deer hunters don’t care whether their rifle shoots 1-inch groups, because 2-inch groups work just fine on deer at “normal” ranges. This might seem odd to twenty- first-century handloaders convinced by friends (and other sources of propaganda) that half-inch groups are necessary for slaying deer, even at “woods” ranges – but it’s true.

Rifles capable of finer accuracy, such as custom-barreled, big-game rifles or varmint-weight factory models, can shoot more accurately with .003 bullet runout, and for the very finest accuracy, measureable runout should be as close to zero as possible. My 6mm PPC benchrest rifle, built by local gunsmith Arnold Erhardt, will consistently group five shots under 0.2 inch at 100 yards – but only when bullet runout on loaded rounds is no more than .0005 inch, half of 1⁄1000 of an inch.

If a particular expander ball die passes this initial test (about a third do), I mark the die-box label with an “OK.” If not, I either try raising the expander ball or use another technique – pushing the case mouth up over the ball.

I started doing this years ago, partly due to noticing the typical three-die sets used for non-bottleneck cases normally result in very straight “necks.” Their sizing dies do not include a typical expander ball. Instead, necks are expanded with a separate die containing a round-nosed cylinder high inside the die. (The expander can also be adjusted to slightly flare the case mouth, which is handy when seating the non-jacketed lead bullets often fired from handguns and rifle rounds like the .45-70.)

After a little thinking, I removed the expander/decapping spindle from a typical expander ball die and sized several cases, which all showed just about zero neck-runout – as they should from good dies. I then replaced the spindle and pushed each case up into the die, just enough to pass over the expander ball. They showed a little more neck runout, but still averaged only .001 to .002 inch. This technique works due to the base of the case being pushed upward by the flat inner surface of the shellholder, preventing the case from tilting as much, if at all.

A few years later it occurred to me – I am often kind of slow – that a third neck-expander die would also work with bottleneck rifle dies. However, after a little more thinking, it also occurred to me that some sets of expander ball dies include both a full-length and a neck-sizing die, and the neck-sizer might work very well for pushing case necks up over the expander ball. I tried this and it worked! However, three-die sets including a neck-sizer cost more than the inexpensive two-die sets so many handloaders prefer to purchase.

Another excellent way to resize necks straightly is to use what are generally known as “hand dies.” These don’t screw into a press, so cases must be pushed into the die by other means. The least expensive version is the original Lee Loader, where the case is typically tapped into the neck-sizing die with a wooden mallet – or even a chunk of 2x4. (Users of more expensive hand dies, like those made by L.E. Wilson, usually use an arbor press.)

If case necks are reasonably uniform in thickness, hand dies result in very fine accuracy, the reason most benchrest competitors use them. However, they can even make a difference in “hunting rifle” accuracy.

When using typical expander-ball dies, this load usually grouped five shots into about .75 inch at 100 yards, but with the Lee Loader ammunition it averaged under 0.5 inch. However, the bullet seater of the Lee Loader also helps. Due to a straight cylinder section, barely above bullet diameter, which keeps bullets aligned as they enter the case neck.

Another solution is to make the neck portion of the sizing die oversized enough to house a “bushing,” a short steel cylinder with a hole in the middle to size down the neck. The hole can vary slightly in diameter, allowing handloaders to match the bushing to the brass.

Again, bushing dies cost more to produce than standard expander ball dies, and each bushing is an additional expense, but for handloaders who want to produce very straight ammunition, they work very well. In fact, the dies I use for my benchrest rifle are Redding Competition dies, with a bushing the correct diameter to barely size down the turned necks of my 6mm PPC brass. The bushing die, along with the micrometer seating die, result in bullet runout no more than .0005 inch.

I also use Redding bushing dies for loading most of my varmint ammunition, in cartridges from the .17 Hornady Hornet on up – but I also ignore Redding’s suggestion to use the expander ball. Instead, I remove the ball, and carefully match the neck diameter of my cases with the right bushing. This allows me to crank out plenty of very straight, accurate ammunition for picking off everything from sub-pound ground squirrels to 10-pound rockchucks and jackrabbits.

Yet another accurate solution is a Lee Precision Collet die, which uses several steel “fingers” to press the case neck around a steel mandrel a little smaller than bullet diameter. This has the advantage of being less expensive than bushing dies, so it can result in straight case necks even if they vary a little in thickness. My present .22 Hornet press die, for instance, is a Lee Collet. This doesn’t size necks quite as straightly as the Lee Loader, but is a lot quicker and quieter.

However, with any neck-sizing system, consistent case-neck thickness tends to enhance accuracy. Several companies sell excellent neck-thickness gauges, but some concentricity gauges, like the RCBS Casemaster, also include a neck-thickness gauge, which tends to enhance accuracy more than weighing every powder charge.