Cartridge Board

.40-65 Winchester

column By: Gil Sengel | December, 21

It is often asked how early black-powder cartridge sizes and bullet diameters were determined. There is little to tell because this work was done by the ammunition companies. In the U.S., this was Winchester, Union Metallic Cartridge, United States Cartridge Co. and of course, Frankford Arsenal. Winchester and Frankford had a great advantage because they could make the cartridges to fit their own gun designs. Others, notably Colt, Marlin and Smith & Wesson, had to either use existing rounds or contract an ammunition maker to design/load what they wanted.

The only records kept of the design of early cartridges were in the files of the ammunition companies or riflemakers. Individual shooters and experimenters didn’t get involved until well into the smokeless-powder era. Multiple sales of these companies over the past 140 years have resulted in such records being tossed out by disinterested new owners. What little remains must be gleaned from makers catalogs of the time – and that isn’t very much.

In 1881, John Marlin’s first repeating rifle appeared. It was chambered (according to Brophy’s book Marlin Firearms) in either .45 Govt. (.45-70) or .40 (.40-60). This would not be true for long.

When the U.S. Army adopted the .45-70 as its infantry rifle cartridge in 1873, it fired a 405-grain, roundnose lead bullet. Cartridge length was 2.56 inches. Riflefolk of the time, much like those of today, wanted a repeating rifle to fire the military round. Winchester scaled-up its M73 lever action, but because of limits to the toggle-lock design, the new M1876 could not fire the new government round. When Marlin’s rifle came along, firing the .45-70-405, it enjoyed a tremendous sales advantage. The Marlin could also be had in a new .40-60-260, a .45-70 case simply necked down to .40 caliber. Cartridge length was identical to the .45-70-405.

rifle. To make matters worse, two months later, Winchester listed its new .40-60-210 round for the M1876 lever action. It was much shorter than the Marlin cartridge so it could function in the M1876.

Also, Marlin had submitted his rifle to a government board in 1881 that was tasked with finding a repeating rifle to replace the trapdoor Springfield. It was rejected in 1882 due to “cartridge explosions in the magazine tube.” This led to the quick availability of the .45-70-405 Marlin cartridge using a flatnose bullet rather than the roundnose military design.

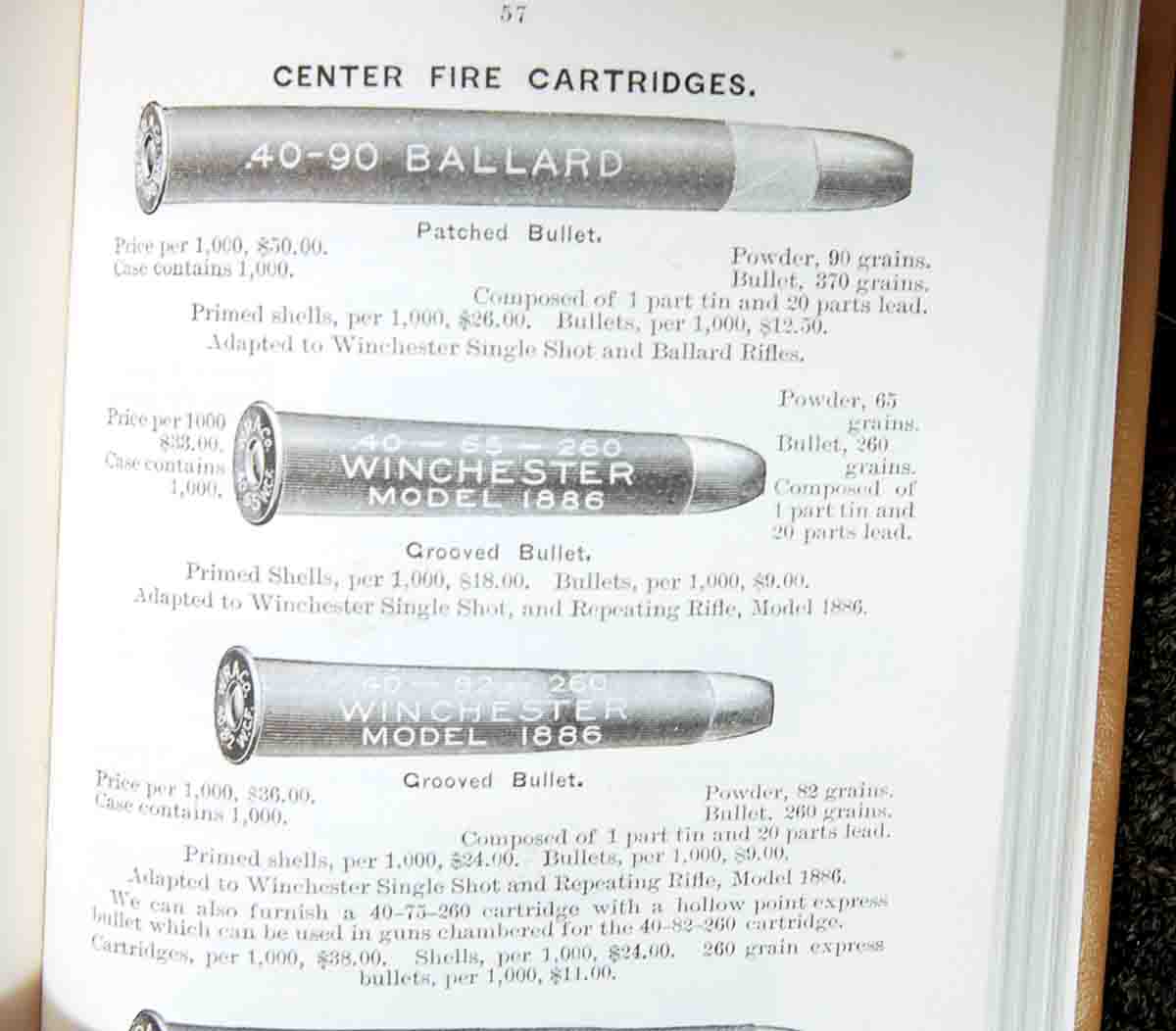

Then came Winchester’s Model 1886, which was both large enough and strong enough to fire both the .45-70-405 and .45-70-500. No mention was made of requiring flatnose bullets. The M86 was also chambered for a powerful .40-caliber round, the .40-82-260. Within a few months, the .40-65-260 Winchester was added, which was dimensionally identical to the .40-60-260 Marlin! Marlin could do nothing but watch Winchester take its sales.

Just why Winchester copied the Marlin round is anybody’s guess. The U.S. in the late 1880s was awash in .40-caliber cartridges. A quick count reveals at least 30, from the .40-40 Maynard to the huge .40-110 Winchester Express. The .40-65 didn’t add a thing. It’s good we no longer create new cartridges that duplicate existing ones.

Ballistics of the .40-65-260 Winchester vary depending upon the reference. Black-powder loads run from 1,300 to 1,420 feet per second (fps). In 1894, Winchester’s catalog shows a velocity of 1,325 fps from a 26-inch barrel. Midrange trajectory at 100 yards is 2.85 inches, 200 yards is 12 inches and 300 yards is 30.67 inches. Muzzle energy would be a little over 1,000 foot-pounds (ft-lbs).

A new 245-grain Metal Patch (full jacket) bullet is also listed using the 65-grain, black-powder charge. No velocity is given. By 1900, the weight of the metal patch bullet was increased to 260 grains and a similar weight softpoint was added. Both are loaded with either smokeless or black powder. The lead slug pushed by black powder is still available.

By 1918, only the black-powder lead and smokeless softpoint cartridges remained. The lead bullet was dropped in 1928 and the softpoint just before World War II. It is surprising that Winchester never offered its “High Velocity” smokeless loading for the .40-65 as it did for the .45-70, .38-55 and a few others. This added 200 to 300 fps to velocity and made the rounds much more powerful at iron sight ranges.

What Winchester did not do, however, Remington-UMC did under the name .40-65 Winchester and Marlin. The company’s 1918 catalogs show 260-grain lead, metal patch and softpoint bullets achieving 1,420 fps, but then there is a “High Power” load pushing a 253-grain softpoint to 1,790 fps. This increases muzzle energy to 1,800 ft-lbs, 54 percent greater than the others. Its 200-yard midrange trajectory of under 8 inches meant that (properly sighted) dead-on holds were possible on big game to at least that range. The load, however, was soon gone.

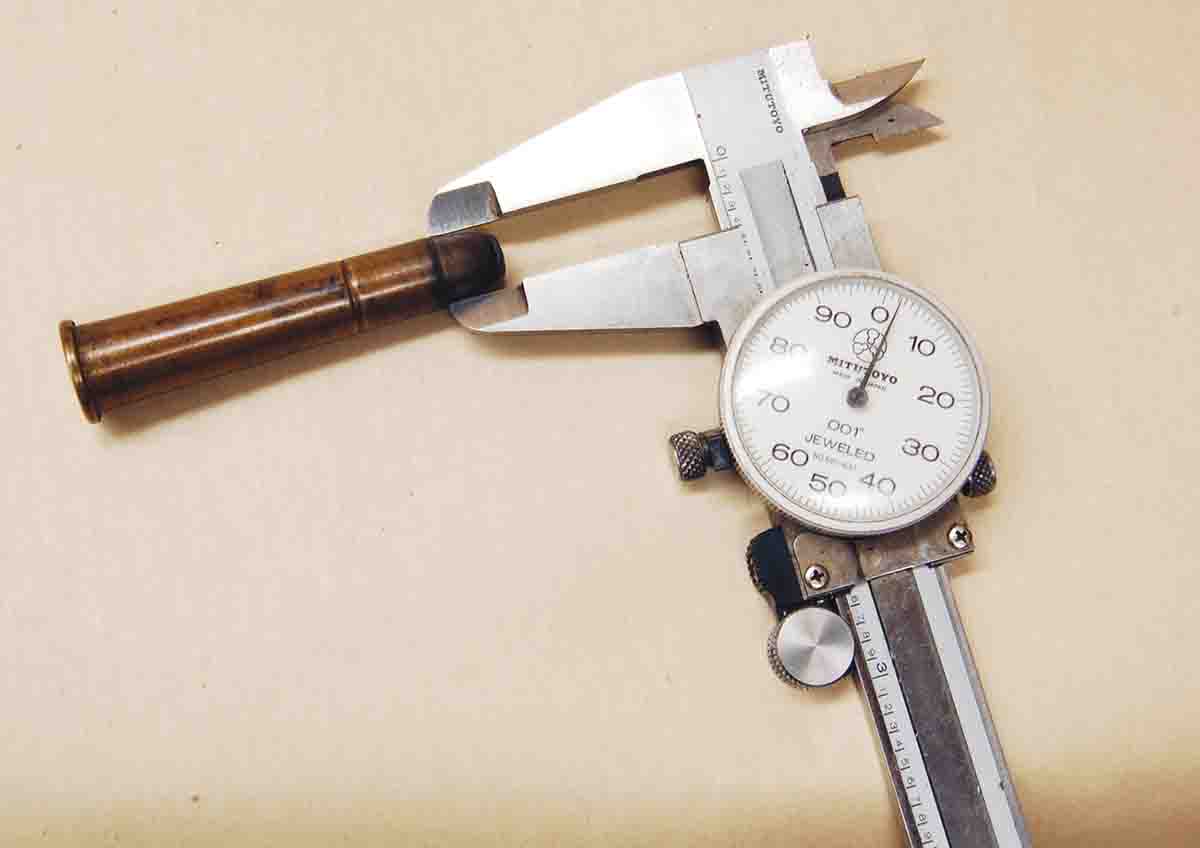

As with other old rounds of the 1880s and 1890s, this should have been the end of the story, but when Black Powder Cartridge Rifle Silhouette became popular in the mid-1890s, shooters looked for a lighter recoiling round than the .45-70. They found it in the .40-65 Winchester, but not using the original 260-grain bullet weight. It was determined that 300 to 400 grains were necessary to topple the 500 meter rams. Original .40-65-260 rifles would not be adequate.

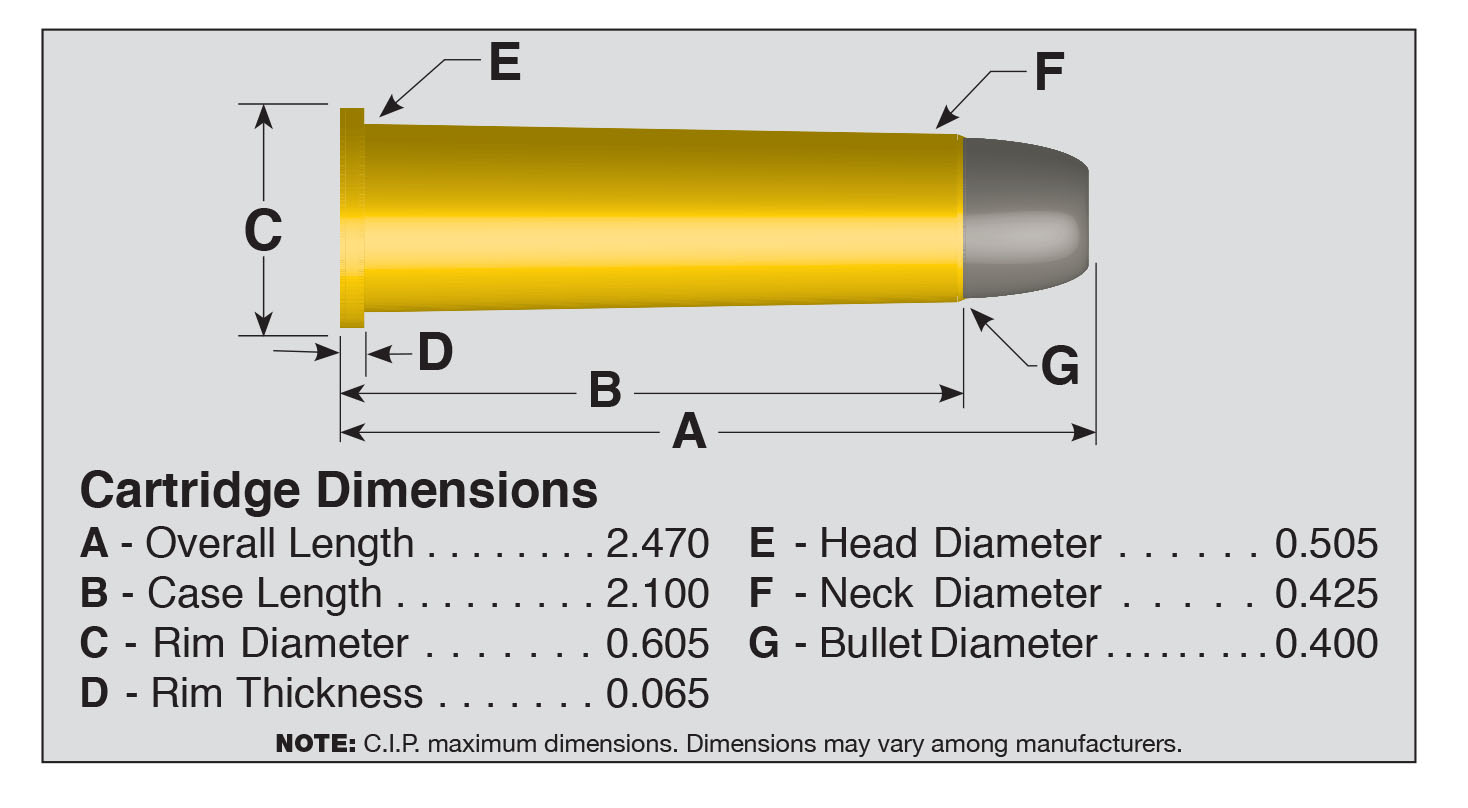

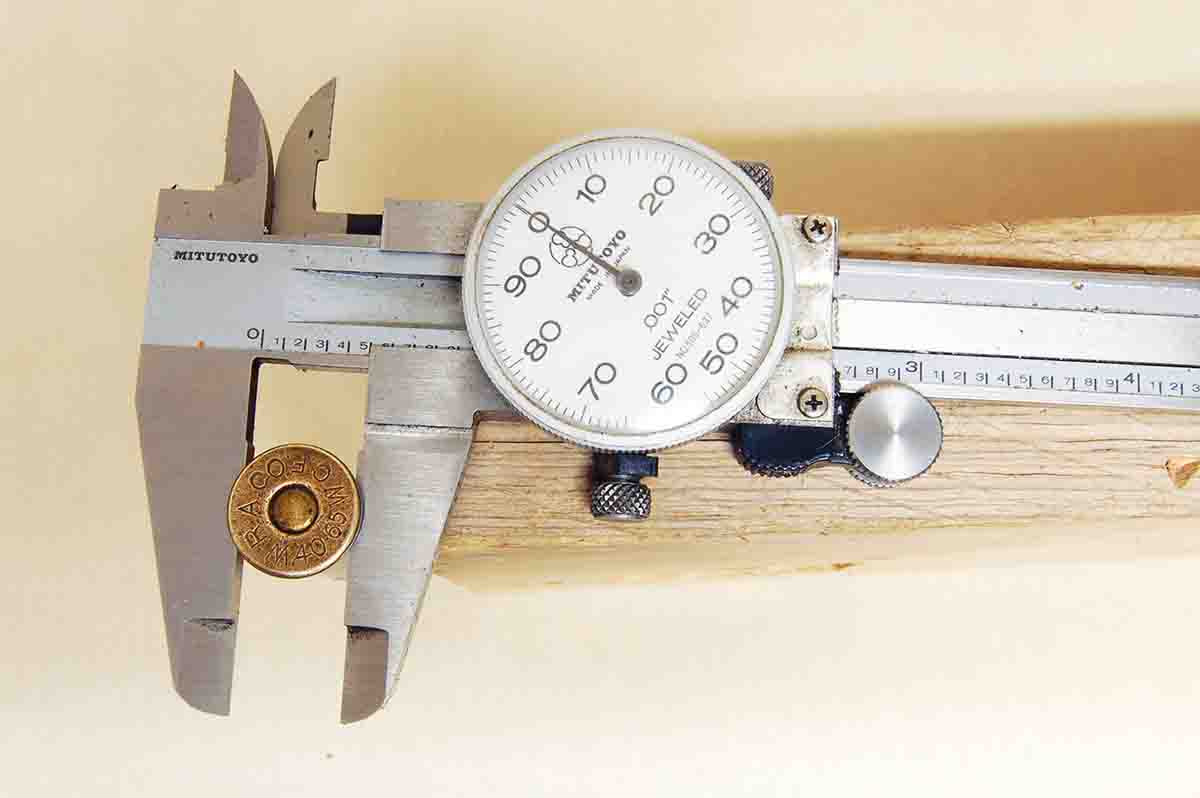

Folks who knew their way around a rifle were fortunately picked for this adventure. First the 1:26 rifling twist rate for the 260-grain bullet was increased to 1:16. Next, the varying bore diameter of the old .40 calibers was standardized at .400 inch (true .40 caliber) and grooves at .408 inch. With so many bullet weights, shapes and throat lengths in today’s essentially custom chambers, the .40-65 Winchester has become an entirely different cartridge than the one available so long ago. The most that can be said is that the heavy slugs, pushed by a case full of FFg black powder, give muzzle velocities in the 1,175 to 1,250 fps-range. Who knows, the .40-65 Winchester and Marlin may be beginning another 60-year run of popularity.

.jpg)