A Trio of Hornets

Updated Loads for the .17, .22 and .22 K-Hornet

feature By: John Barsness | June, 18

However, all successful new technologies evolve quickly. “Flying machines” also rapidly improved from the 1880s to 1950, from balloons to the Wright brothers to supersonic jets – but that doesn’t mean airplanes or rifle powders haven’t improved since.

But rifle cartridges at either end of the capacity spectrum suffered for decades under a far more limited range of powders. That started to change for “magnums” in the 1940s with IMR-4350 and H-4831, and over the next several decades new slow-burning powders emerged each year like April flowers. Unfortunately, during the same period not much changed for really small centerfire rifle cartridges, and the poster child for these unlucky rounds is the .22 Hornet.

In 1920 a major ballistic gap existed between .22 rimfires and the .25-20 WCF. The Hornet was designed to plug this gap by beating the velocities of “high speed” .25-20 ammunition. Final development took place in the late 1920s at the U.S. military’s Springfield Armory, where Col. Townsend Whelen was director of research and development, using rechambered 1903 Springfield rimfire training rifles. Thanks to publicity from gun writers (including Whelen), Winchester introduced Hornet ammunition in 1930 before any rifle factory chambered the round. The first loads featured blunt-nosed, 45-grain hollowpoints or 46-grain full-jacketed bullets, primarily due to the 1:16 rifling twists of rimfire barrels used in both custom and factory rifles. However, back then many shooters also considered blunt bullets more accurate than spitzers, especially in smaller-caliber rifles.

The first factory ammunition was listed at 2,350 fps, but in 1934 Hercules introduced a spherical powder it called 2400, named

During World War II, .30 Carbine ammunition was loaded with a new spherical powder that had a slightly slower burn rate than IMR-4227. After the war it was sold to handloaders as Winchester 296 Ball Powder. Soon Hodgdon offered a similar powder called H-110. (Today Hodgdon distributes Winchester-brand powders and lists identical charges for W-296 and H-110 because they are the same powder, made in the same factory.) In 1946 the factory velocity for .22 Hornet ammunition reached 2,690 fps then stayed there for decades, frozen in time like the woolly mammoths still occasionally found in Siberian ice.

I bought my first two handloading manuals in 1966, the Lyman Ideal Handbook No. 42 and Speer Manual for Reloading Ammunition Number 6.

Lyman only listed four powders for loading the .22 Hornet – Hercules 2400, IMR-4227, H-110 and a Hodgdon powder similar to 2400, H-240 that was discontinued in the 1960s. Speer listed the same powders, along with Hodgdon H-4227.

The .22 Hornet’s popularity started dropping in 1950 after the appearance of the .222 Remington in that company’s Model 722 rifle, a postwar “short” bolt action. The .222 held about twice as much powder as the Hornet, and the 722 had the same 1:14 rifling twist as .220 Swift rifles. The original factory load featured a 50-grain spitzer at 3,200 fps, resulting in considerably more utility than the .22 Hornet, with finer accuracy and only slightly more recoil.

The .222’s immediate and spectacular success resulted in yet another .22 Hornet handloading problem: Original rimfire Hornet barrels had rimfire bore dimensions, so bullet companies made slightly smaller diameter, blunt Hornet bullets, along with .224-inch spitzers for “modern” cartridges like the .222 Remington and .220 Swift.

The powder situation remained the same until about 1980 when Winchester 680 appeared, which eventually became Accurate Arms 1680. Several years ago, Western Powders bought Accurate Arms and today sells a more consistent powder called Accurate 1680. With a burn rate too slow to increase velocities in the .22 Hornet very much, A-1680 works very well in the .17 Hornet.

In the late 1980s, Nosler initiated another technological advance with its Ballistic Tip bullets. One long-time problem for all .224 varmint cartridges was the relatively low ballistic coefficient (BC) of softpoint and hollowpoint spitzers. While hollowpoints with tiny openings had decent BCs, they expanded less consistently than softpoints – and if the opening was enlarged enough to enhance expansion, BC dropped. Plastic-tipped bullets both expanded violently and increased BC.

At the turn of the twenty-first century, the .22 Hornet received its first substantial powder improvement since W-296/H-110. Primarily designed for reloading .410 shotgun shells, Hodgdon Lil’Gun also turned out to be practically perfect for 40-grain bullets in the .22 Hornet. Combining a Hornady V-MAX, Nosler Ballistic Tip or Sierra BlitzKing bullet with Lil’Gun resulted in ammunition that shot a little flatter than the original 50-grain softpoint spitzer load for the .222 Remington, yet used far less powder – and at lower pressures than previous Hornet powders.

The Hornet’s popularity started rising again but ran into another technical roadblock. Because original .22 Hornet ammunition was loaded with blunt-nosed bullets, rifle magazines were very short. Seating plastic-tipped 40s to fit inside standard factory magazines usually resulted in the curve of the bullet’s ogive way down inside the neck, and the partially exposed case mouth often hung up when sliding from the magazine into the chamber.

Luckily, the .22 Hornet’s neck length is .323-inch, even longer than the .308 Winchester’s. Some handloaders found they could trim Hornet cases shorter, and still retain enough neck length to hold longer bullets firmly, so cartridges fed slickly. Other handloaders (including me) found single-shot Hornets allowed 40-grain plastic tips to be seated much further out, increasing powder room.

Meanwhile, many bullet companies still produced relatively short, 40-grain softpoint and hollowpoint bullets, and the wide variation in bullet lengths resulted in a wide range of 40-grain Lil’Gun data. Hodgdon’s listed maximum charge for the Speer 40-grain softpoint of 13.0 grains just about fills the case to the mouth, but the Speer bullet is only about two-thirds the length of the longest 40-grain plastic-tip bullet. As a result, there isn’t room to seat 40-grain plastic tips to the standard SAAMI 1.732-inches over- all cartridge length without considerable powder compression.

Several bullet companies list one maximum load for all their bullets of a certain weight, even if some bullets provide more powder room and/or less pressure. This is one reason maximum Lil’Gun loads for 40-grain bullets vary from 11.0 grains in Nosler’s latest manual to 13.2 grains in Hornady’s.

The low Nosler maximum probably isn’t due to high pressure, but a lack of powder room. When its fifth manual appeared in 2002, Nosler still made a blunt-nosed, 45-grain Hornet bullet. The maximum Lil’Gun charge was 12.5 grains, almost 14 percent larger than today’s 11.0 grains for the 40-grain Ballistic Tip.

The 45-grain bullet’s muzzle velocity was 2,749 fps in a 22-inch barrel, a little slower than the 2,762 listed for 11.0 grains of W-296. Hornady’s manual also shows the highest 40-grain velocity with W-296/H-110, again probably due to powder space, since the company’s V-MAX is the longest 40-grain plastic-tip bullet. Hornady also lists 2400 as matching the Lil’Gun’s 2,800 fps – about 250 fps more than the top velocity Alliant lists for 2400 with 40-grain bullets.

Aside from bullet length, primers can be another reason for load-data variation in the .22 Hornet. For decades one “secret” Hornet handloading technique was to use small pistol primers, but handloading manuals advised against it because of the thinner cup of pistol primers. Speer eventually ran some tests, and in its 14th manual announced pistol primers were safe and also reduced velocity variations, the reason handloaders who used them often obtained better accuracy. As a result, all .22 Hornet loads for the 14th manual were shot with CCI 500 primers.

However, in my own .22 Hornet experiments with Lil’Gun, CCI 450 Small Rifle Magnum primers produced the finest accuracy, slightly better than CCI BR-4 benchrest primers. In the same test, CCI 500s resulted in the worst accuracy of several primers tested. Many other handloaders report similar results, probably because Lil’Gun’s somewhat harder to ignite than some other Hornet powders.

The “improved” version of the .22 Hornet, called the K-Hornet, along with Hornady’s version of the wildcat .17 Hornet, also exhibit more sensitivity to powders and primers than larger cartridges. This makes sense, because in such tiny cases any slight variation in brass, bore diameter and chamber dimensions makes more difference than in larger cartridges. This is exactly why today’s wider variety of suitable powders and primers helps Hornet handloaders.

Two other useful powders appeared after Lil’Gun, Alliant Power Pro 300-MP and Hodgdon CFE BLK. Like all other “Hornet powders” introduced after 2400 and IMR-4227, both were primarily designed for other purposes; 300-MP for magnum handgun cartridges and CFE BLK for the .300 AAC Blackout. Alliant 300-MP is slightly slower burning than Lil’Gun, and CFE BLK is slightly slower than A-1680.

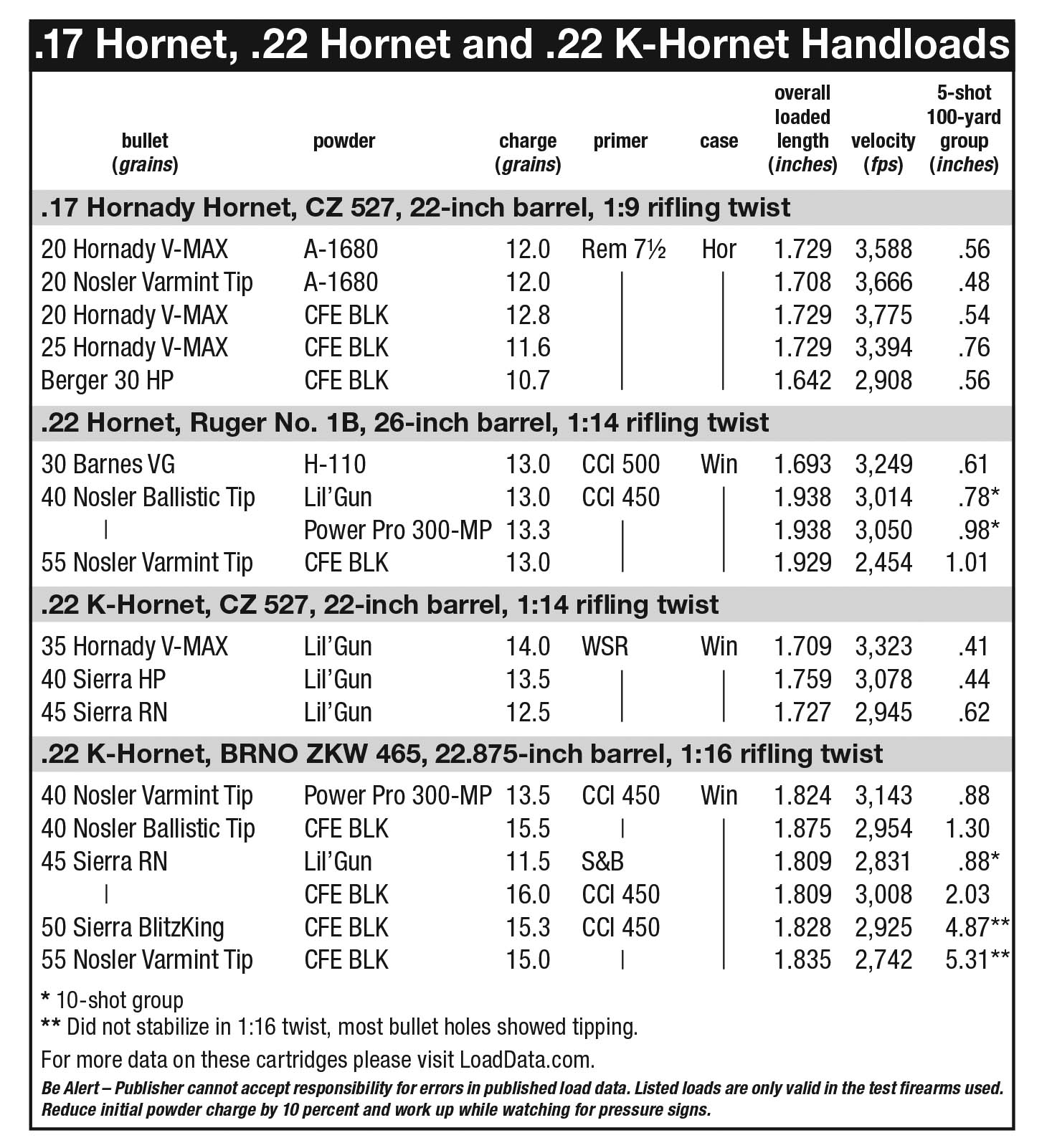

Which powder works best depends on the particular Hornet cartridge, and often bullet weight. The .22 Hornet I’ve shot for 15 years is a Ruger No. 1B, which allows 40-grain plastic-tip bullets to be seated out to an overall length .2 inch longer than standard Hornet magazines. As a result, there’s plenty of room for 13.0 grains of Lil’Gun, or 13.3 grains of 300-MP. The Power Pro 300-MP charge exceeds Alliant’s listed 11.7 grain maximum considerably but results in essentially the same 2,944 fps muzzle velocity listed by Alliant, allowing for the 26-inch barrel on the Ruger, and measuring case expansion indicates pressure is similar to the Lil’Gun load.

The .17 Hornet wildcat was based on the .22 K-Hornet necked down, but when Hornady introduced a commerical version in 2012, the case had been shortened enough to easily use plastic-tipped bullets in standard-length magazines. While Lil’Gun will work in Hornady’s .17, some handloaders have experienced loose primer pockets with Hodgdon’s listed maximum charge of 10.0 grains, probably due to the primer. Hodgdon’s tests used a Federal 205M, one of the milder small-rifle primers, and hotter primers increase pressures. However, that’s largely irrelevant, since slower powders work better in the .17 Hornet anyway. My CZ 527 prefers Remington 7½ Benchrest primers to any others tested with both A-1680 and CFE BLK.

In my present BRNO .22 K-Hornet, 300-MP did slightly better with the same CCI 450 primer preferred by the Ruger No. 1. Luckily, the BRNO has a magazine .06 inch longer than standard SAAMI length, allowing the use of plastic-tip, 40-grain bullets without any problems, though the 1:16 rifling twist won’t fully stabilize bullets over 40 grains. I still included CFE BLK data for heavier bullets in the chart, in case somebody has a 1:14 twist K-Hornet, because it produces higher velocities than any other powder tried.

Also included is data for my first K-Hornet, a CZ 527, but that rifle was sold a decade ago because the magazine was too short for long, plastic-tipped bullets. Despite the high velocities possible with all the bullets tried, they didn’t shoot as flat as 40-grain plastic-tip bullets from the Ruger No. 1, so the CZ went down the road.

While experimentation with bullets, powders and primers to determine what works best in your rifle is standard handloading technique, it’s even more critical when loading the little Hornet cartridges.