Cartridge Board

9.3X64mm Brenneke

column By: Gil Sengel | June, 18

Wilhelm Brenneke was born in 1865 in Prussia, then part of the German Empire. It is recorded that by age 10 he was fascinated by anything that launched a projectile. Soon he acquired a small rimfire, and began making crude rifles on his own. He was formally educated as a machinist, toolmaker and mechanical designer. By 1895 he owned his own company selling his designs in firearms, ammunition and bullets used by other ammunition makers. Brenneke seems to have been a bit of John Browning, Charles Newton and Roy Weatherby all rolled into one.

Our interest here is cartridges, and to that end Brenneke was an avid hunter. Growing up at the end of the black-powder era, he was not satisfied with the performance of lead bullets and old propellant. He believed bullets with metal jackets were needed to produce uniform expansion and humane kills, but only when combined with higher velocities. Brenneke was constantly testing his ideas for such bullets and cartridges. By the Great War he was selling rifles for two new rounds based on the German 7.92x57mm case lengthened to 64mm. One was an S-bore (.323-inch bullet diameter), the other a 7mm that was virtually identical to the .280 Remington that would come along 40 years later.

Brenneke’s two cartridges developed muzzle velocities in the 2,800- to 3,000-fps range. Bullets, however, had a tendency to come apart at close range and failed to expand uniformly as distances increased. He then designed a steel-jacketed, multipurpose bullet known as the Torpedo Ideal Geschoss (TIG). Later a Torpedo Universal Geschoss (TUG) was created for deeper penetration. An interesting feature of the design

is a small shoulder called a Scharfrand (sharp edge) located on the bullet’s ogive. Only about .015 inch in width, the shoulder is intended to cut a clean entrance hole in animal hide, allowing free-bleeding from the wound. It remains on the bullets today.

Brenneke was also working on a larger-caliber cartridge. If given modern bullets and high velocity, he believed it would suffice for everything except elephant, rhino and back-up duty for stopping charges of the largest animals; the big British doubles could handle that.

World War I then put an end to sporting cartridge development for several years. By the mid-1920s the .375 Holland & Holland Magnum was proving itself on the large, wild cattle of Asia, tigers in India and most everything in Africa, with any errors in application memorialized on tombstones.

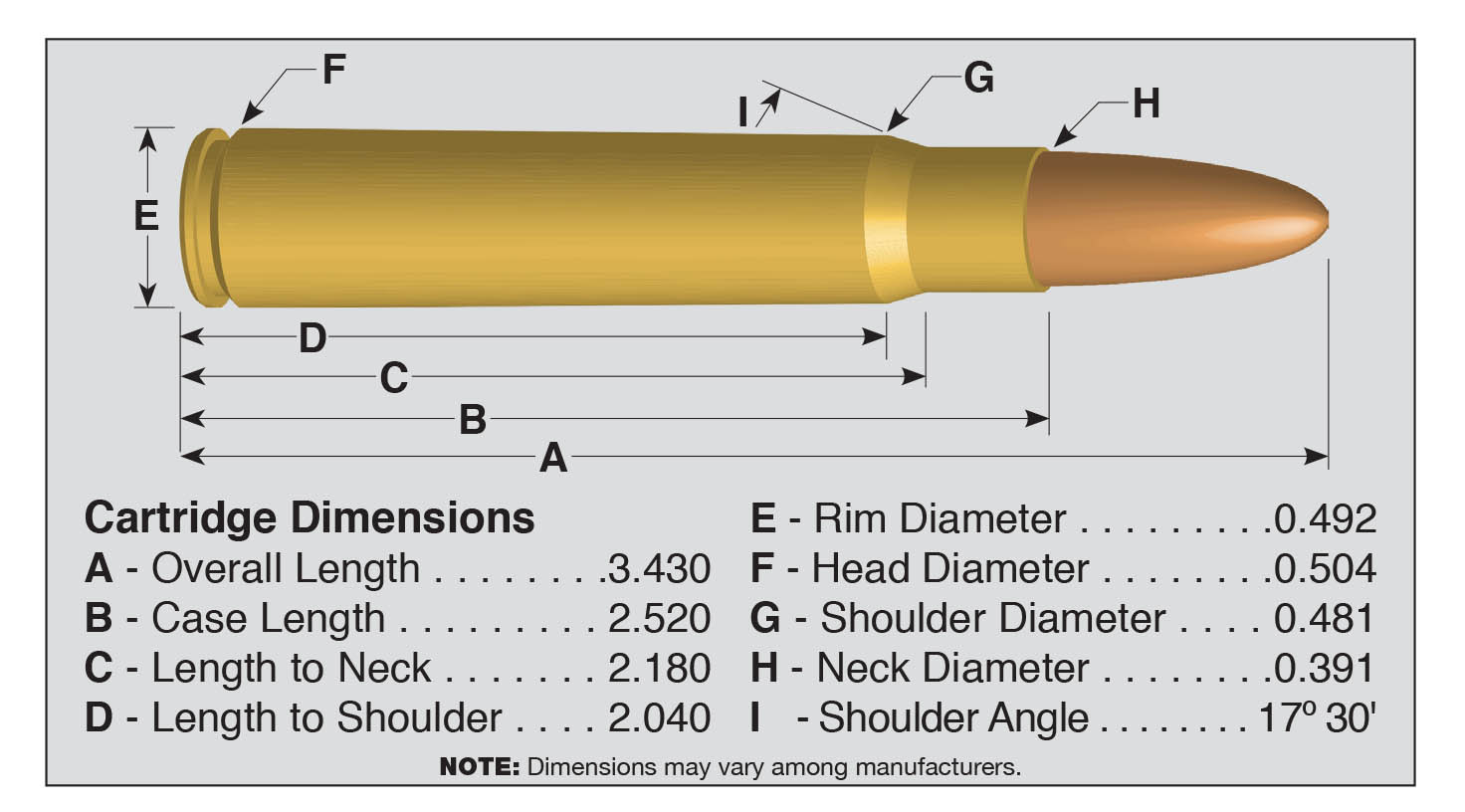

Brenneke was aware of this and set out to duplicate the successful .375’s ballistics in his new cartridge. Bullet diameter would be the old German favorite 9.3mm (.366 inch). The long, temperature-sensitive strands of cordite propellant of the .375 H&H would not be used, so the new case could be shorter and much less tapered.

Powder capacity would, however, have to approach that of the H&H cartridge. To do this, the unneeded belt was removed, leaving a base diameter of .505 inch and creating an entirely new case. Length was set at approximately 2.522 inches (it varies a bit) with a neck length of just under one caliber, an 18-degree shoulder and the case body blown out to only a little over .010 inch per side taper from base to shoulder.

The cartridge became known as the 9.3x64mm Brenneke. The year of introduction is often questioned, but 1927 is very close. Most importantly, the cartridge was the largest that would fit in what was becoming known as a “standard-size” action. Friend John Gannaway has made it possible for us to see an original 9.3x64 made in Wilhelm Brenneke’s shop. The photo shows the unaltered rifle and its Hensoldt scope in claw mounts. It weighs 10 pounds, 3 ounces with a 25.6-inch barrel. Light border engraving and a few oak leaves add a touch of class.

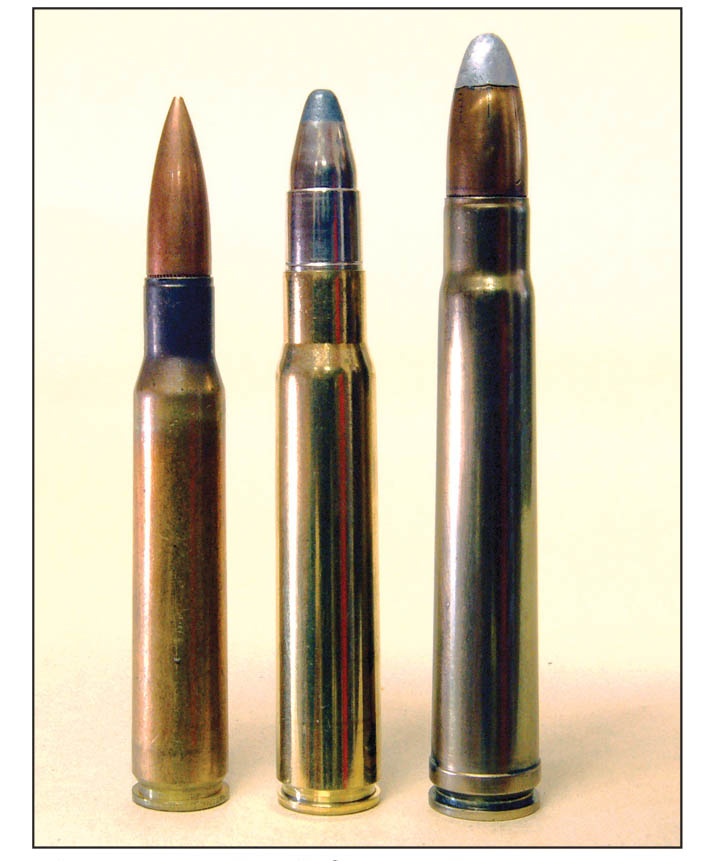

As for the cartridge, the 9.3x64 bullet, case and physical size go together perfectly. It’s big and seems to exude power. Holding one in the hand makes it obvious it’s not a .30-06. Touching off a round containing a 286-grain bullet at over 2,600 fps makes it very obvious it’s not a ’06!

Given ballistics comparable to the .375 H&H, reasonably priced rifles and the reliability of the M98 action, it would seem that the 9.3x64 would have been quickly successful. Such was not to be. The reason was due to bullets and competition from an existing cartridge.

The bullet problem was that it didn’t hold together and penetrate in many instances. This occurred on both dangerous game and lightly constructed species. Given that the 9.3x64 generated 200 to 250 fps greater velocity than the other 9.3s of the time, it must have been loaded with the same bullets as the slower numbers to forgo the expense of making special bullets for a cartridge that would have limited sales.

No matter how good the 9.3x64 Brenneke was, it had to sell against gunmaker Otto Bock’s immensely popular 9.3x62 Mauser cartridge of 1905. Despite being smaller in case diameter and having about 16 percent less capacity, its bullets worked perfectly at the velocities generated. The Brenneke got a bad reputation, especially in Africa, then World War II ended sport hunting.

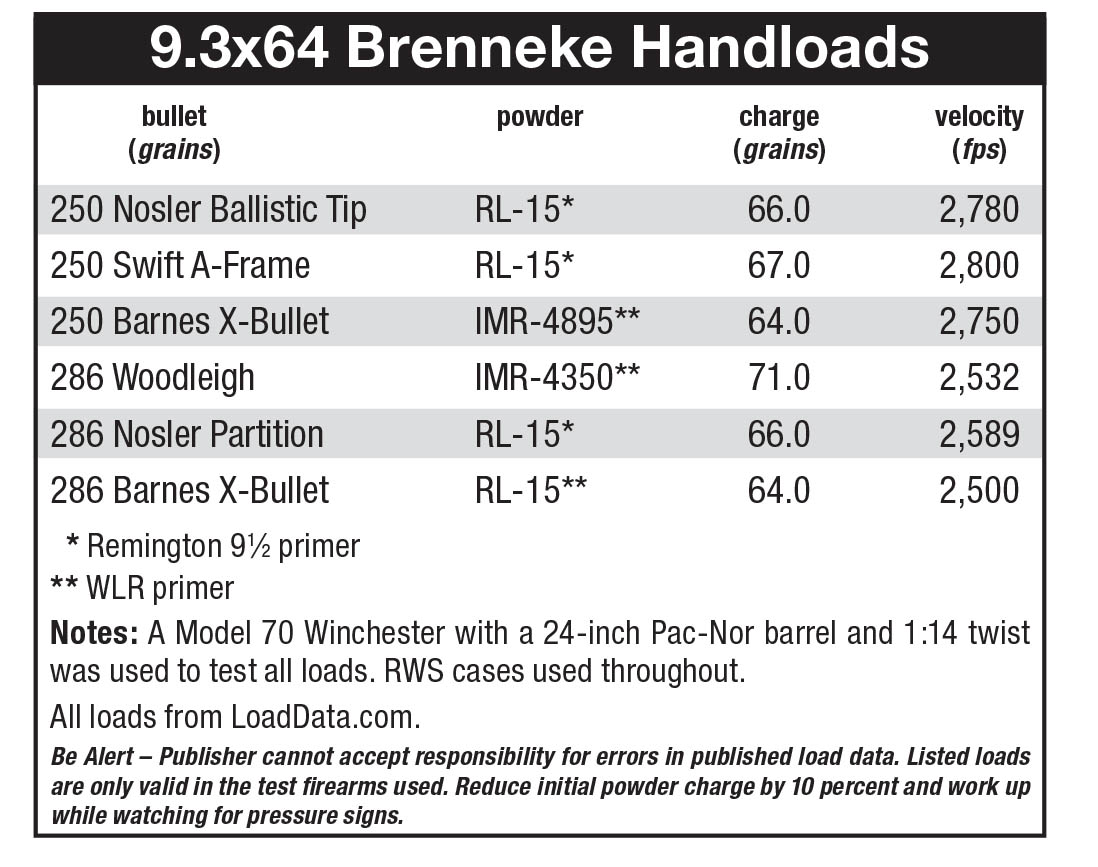

After cartridges again became available in the 1950s, reports from Africa indicated the bullet problem remained. There has recently been talk of tougher bullets in factory loads. RWS has offered loads featuring a 247-grain softpoint at 2,750 fps muzzle velocity, a 285-grain at 2,650 fps and 293-grain bullet pushed to 2,550 fps. All three yield well over 4,000 foot-pounds of muzzle energy, putting it on par with the .375 H&H Magnum and ahead of the 9.3x66mm Sako. Handloads using today’s powders can add a bit to this as well.

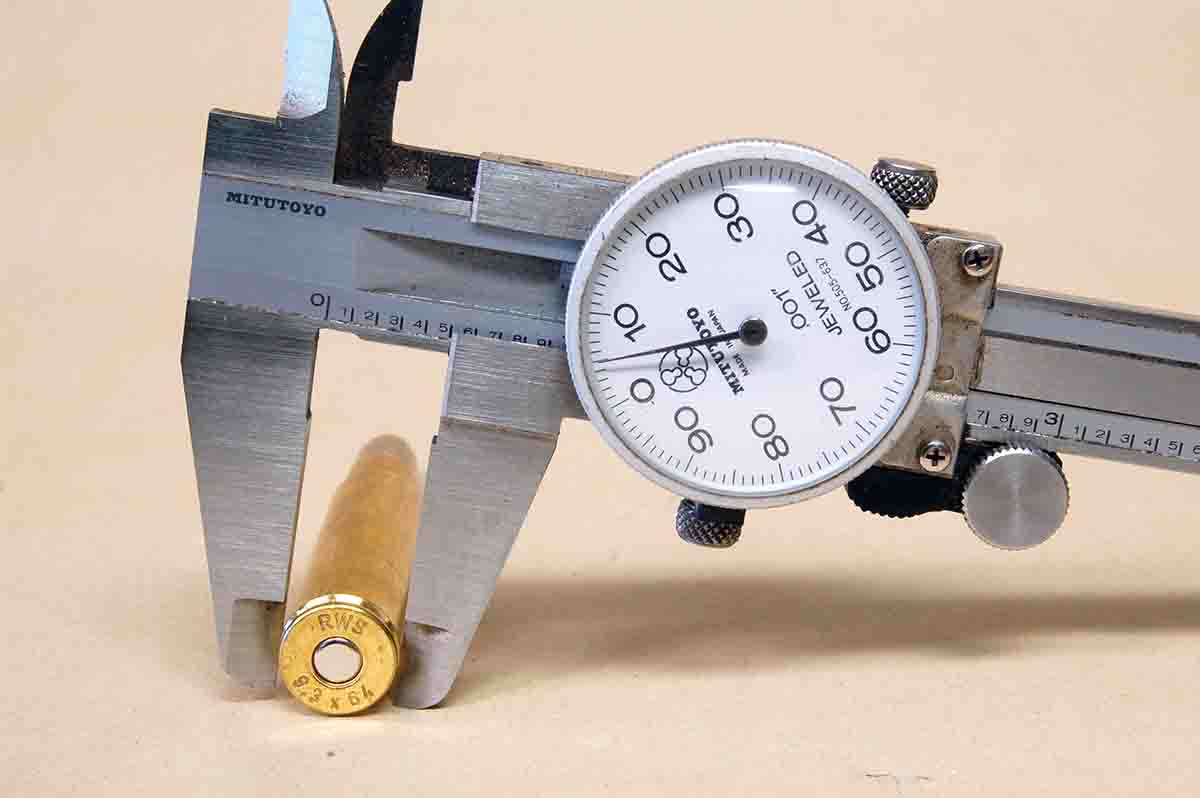

Factory ammunition is really a rather moot point as it seems to be hard to find, especially in North America. Nevertheless, with new rifles chambered for the 9.3x64 Brenneke available in Europe and used rifles not too difficult to find, the cartridge is tailor-made for the handloader. At least two sources, Bertram and RWS, sell empty cases. These can also be formed from .300 Winchester Magnum brass by first turning off the belt, but it’s a process only advanced handloaders can love! There are many tough 9.3mm custom bullets available that easily withstand the impact velocity of the 9.3x64. Look for firms that sell hard-to-find components like Huntington Die Specialties.

There is also plenty of up-to-date loading data available. Swift Bullet Company’s Reloading Manual Number Two gives data for both its 250- and 300-grain A-Frame bullets. Woodleigh Bullets lists 62 combinations for the company’s 250-, 286- and 320-grain bullets. The book African Dangerous Game Cartridges by Pierre van der Walt contains 118 loads using at least 10 powders.

The 9.3x64 Brenneke is an efficient medium bore that can hammer targets close up and, with proper bullets, lengthen the hammer’s handle to reach 250 yards or so. It has just had a string of bad luck involving wars, bullets and African countries that limit cartridges that can be used for dangerous game to bullets of .375 inch or larger. Nevertheless, it is an amazing cartridge for the handloader who has a need for its power.