Practical Handloading

Bullet Pullers: Which to Use?

column By: Rick Jamison | June, 18

After a bullet is pulled, the powder and bullet are contained within the hollow plastic, so the cap must be unscrewed and the powder and bullet

Instead of using the case rim gripper supplied with an inertia puller, it can be replaced with a standard shellholder, which does not come apart when the retaining band becomes weak on the three-piece retainer. However, if heavy pounding is required when pulling a lightweight bullet, a case rim is more likely to be damaged with a standard shellholder.

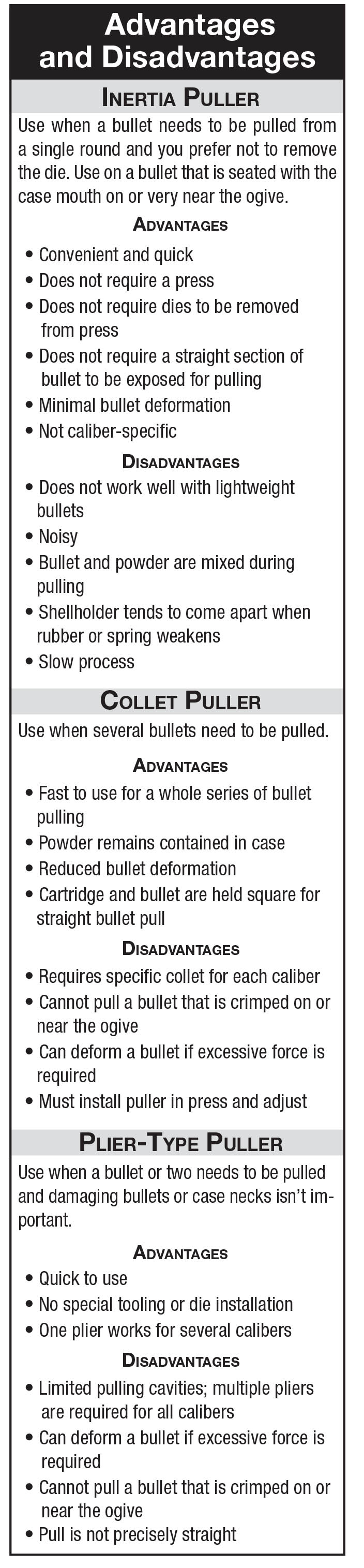

The second type, a collet puller, is used in a loading press. It has a die body with standard 7⁄8x14 die threads and is threaded into a loading press. A collet or sleeve with slits allows the lower end of the sleeve to be squeezed tighter by turning a lever on top of the die. This forces the collet into a tapered housing, reducing the circumference at the lower end and tightening around a bullet. A separate collet size is necessary for each bullet diameter. A cartridge is placed in the press shellholder, the ram is raised to insert the loaded bullet into the collet, the collet is tightened, and then lowering the ram pulls the case off the bullet.

A collet puller is great for pulling bullets from a lot of rounds. It is fast to use once set up. When adjusted, the top lever needs to be moved only a partial turn to grip or release a bullet. When pulled, the bullet is separated from the powder. The powder is contained within the upright case for

A collet puller does not work well when a bullet is crimped on an ogive, or near it, as is the situation with many pistol cartridges. The reason is that the collet needs a straight section of bullet for gripping. However, since this type of puller does not rely on inertia, it works well for lightweight bullets as well as heavy ones. As long as the collet-tightening force is controlled, bullet deformation is minimal.

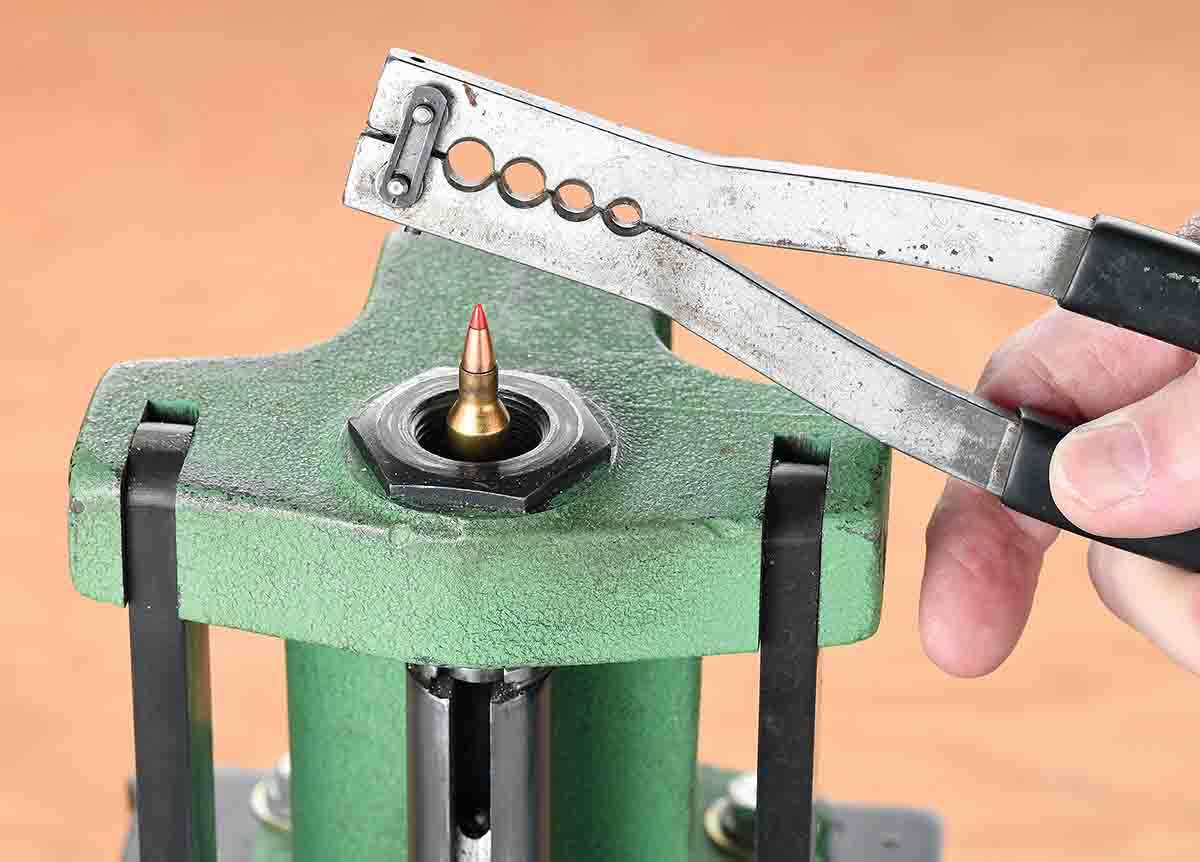

The third bullet puller, the one I call the “plier type,” somewhat resembles a pair of pliers. Rather than having the pivot point between the gripping handles and the jaws, however, this puller has the pivot point at the extreme end away from the handles. There are a series of cavities of different circumferences with half of each cavity in each side of the plier handles. In use, a cartridge is placed in a press shellholder, then the ram is raised until the bullet extends through the die receptacle in the press. The bullet is then gripped with the plier-like device using the cavity size appropriate for the diameter of the bullet being pulled. The press ram is then lowered to extract the projectile. This type of puller needs a straight section of bullet for gripping like the collet puller. It cannot grip a bullet on the ogive. Also, since it requires the gripping motion applied with a user’s hands, a bullet can be deformed with this type of puller. Its use requires enough gripping force to keep the bullet from slipping while being pulled, but not too much grip force so as to deform the bullet. With practice, the correct pressure is usually determined. This puller does require a press, and a die cannot be installed in the press when the puller is used.

Bullets are expensive and once pulled, a handloader may still want to shoot them. So how does bullet pulling affect accuracy? It depends. I once ran tests using tough bullets designed for big game with a lot of straight section extending from case mouths for gripping. The result was that bullets pulled with all three systems shot well. None of the bullets had been visually damaged to any appreciable extent.

However, it is true that either the collet puller or the plier-type puller can deform a soft bullet, such as a varmint bullet, when pulling. So how much does this deformation affect accuracy? Thin-jacket and soft lead-core varmint bullets are the easiest and most likely to be deformed, so I chose those for a recent test. I loaded, pulled, and then fired Hornady 55-grain V-MAX bullets from .22-250 Remington cartridges. When these bullets are seated to SAAMI overall length specifications, there is almost no straight section of the bullet remaining above the case mouth. This makes them very difficult to pull with a plier-type puller, and the bullets were notably deformed when pulling with this device. I pulled 10 of them, and also 10 each with a collet puller and an inertia puller. The inertia puller left almost no marks on bullets, while the collet puller deformed bullets slightly.

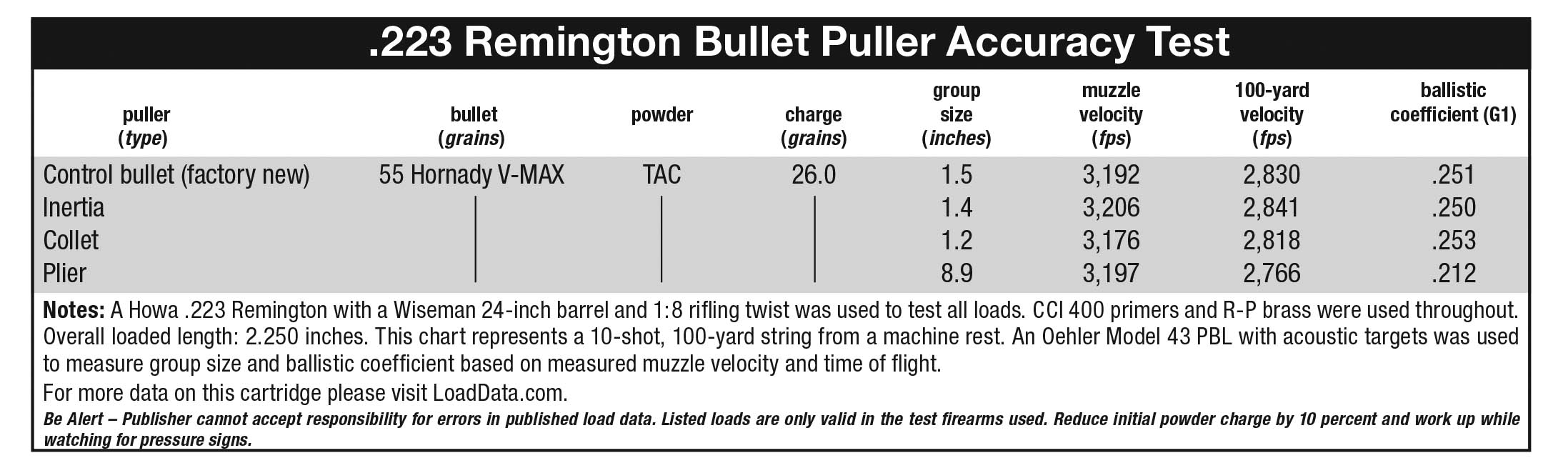

The bullets were reloaded into four batches of .223 Remington cartridges. There were 10 rounds each for the collet, plier and inertia pullers, and another 10 rounds as a control batch using factory-new component bullets. The Hornady 55-grain V-MAX load contained 26.0 grains of TAC propellant with an overall loaded length of 2.250 inches. I then fired a 10-shot string of each batch at 100 yards to see how pulling devices affect accuracy. The results are spelled out in the accompanying table. In summary, the plier-pulled bullets were the only ones affected significantly. They were severely deformed and the results are not surprising.