Reloader's Press

The Infamous .44 Magnum

column By: Dave Scovill | June, 18

We were also advised how the S&W .44 Special evolved from the most accurate big-bore cartridge to come down the pike, the .44 Russian that was .10 inch shorter than the .44 Special case but used the same 246-grain roundnose lead bullet. That was followed by some gobbledygook about how the .44 Special was originally loaded with some new smokeless powder that bulked up so much it required the use of a .10-inch longer case. No one seemed to know the name of the new mystery powder, but it was, nonetheless, one of the standard talking points in any discussion about the history of the .44s.

At any rate, sometime in the early 1970s a Hawes Western Marshal .44 Magnum with a 6.5-inch barrel showed up on a table at a local gun show, and I took the big .44 home. While the frame of the Hawes was/is a bit larger than a Colt SAA, it handled well enough and seemed to shoot where the sights were pointed. I was shooting a Smith & Wesson Second Model Hand Ejector .44 Target at the time, and the same .44 Special loads used in the S&W, 13.5 grains of 2400 with the Markell cast bullet copy of the Lyman/Keith bullet, were initially used in the Hawes. The Clint Eastwood film Dirty Harry came out in late 1971 and was still burning in the minds of some who lusted after the “most powerful handgun in the world,” and you couldn’t find a box of .44 Magnum factory loads or a Smith

Well, the inevitable finally happened, and one of the Keith loads found its way into the Second Model. My first reaction to the shot was to look at the gun, to see if all the parts were still attached. They were, and it immediately became standard practice to never stuff .44 S&W Special cases with such a load again. The problem was I still didn’t have any .44 Magnum brass or factory loads.

Perusing local sporting goods stores and gun shows from the Columbia River to the north and the Oregon/California border to the south, Smith & Wesson .44 Magnums and ammunition remained illusive for quite some time. I did, however, locate a few boxes of .44 S&W Special factory loads and the occasional box of .44 Russian that apparently had become obsolete almost overnight, but which, prior to the advent of the .44 Magnum, had been somewhat popular target and plinking loads in Smith & Wesson and Colt .44 Specials or relatively rare .44 Russian revolvers. In the meantime, I wound up shooting a lot of .44 Special loads in the Hawes and found it to be capable of excellent accuracy, easily the equal of the Smith & Wesson Second Model Target and later a Colt SAA .44 Special.

While I was basically stuck with the .44 Special and a couple of other sixguns chambered for the .38 Special and .45 Colt, I was more interested in the Special than the Magnum and eventually acquired a few Smith & Wesson reference books, two of which stated that the .44 Special was originally loaded with 26 grains of black powder – no mention of any bulky smokeless powder. That left Julian Hatcher as the only source known to me at the time that cited the bulky smokeless load that made it necessary to lengthen the .44 Russian case.

Ironically, while research on the .44 Special failed to shed any light on the name of the bulky smokeless powder Hatcher was referring to, it was information provided by Phil Sharpe on page 172 of his Complete Guide to Handloading (1937) regarding the development of the 1909 .45 Colt military load that finally shed some light on the matter.

The first use of RSQ was in the Model 1906 .45 Colt experimental cartridge and afterward in the Model 1909 .45 Colt, in which it replaced Bullseye. While it would appear that Hatcher was aware of the search to find a bulky smokeless powder to replace Bullseye, which was probably RSQ, he may not have been aware that it was not available to the civilian market until 1909, five years after the .44 S&W Special went public, and was discontinued in 1911.

Compared to the .44 Special loads I had been shooting for quite some time, the Remington factory loads were, well . . . shocking. My first thought was to wonder how they could harness that kind of power in a handgun. The fireball that erupted from the muzzle of the 6.5-inch Hawes barrel in the evening shade was almost blinding, and recoil . . . simply awe inspiring. It was about like touching off that one shot of 17.5 grains of 2400 with the 250-grain Keith-type cast semiwadcutter in the relatively lightweight Smith & Wesson Second Model .44 Special Target with factory stocks, nasty but controllable.

Shooting up 50 rounds of Remington .44 Magnum factory loads taught me that if there are any discrepancies in shooting technique, they will show up almost immediately, especially in the plow-handled Hawes. So it took a while to get used to handling the revolver consistently and properly while shooting. Beyond that, it soon became easy enough to handle, but since it wasn’t legal to hunt big game with handguns in most states in those days, I adopted the Lyman No. 429421 cast bullet seated over 20 grains of 2400 at roughly 1,200 fps. This was about the same as Elmer Keith’s heavier load in a 4-inch barrel, according to the Lyman manual on hand, and was nearly perfect for regular use when hunting varmints or small game.

While it seemed every gun writer in the business was fawning over the .44 Magnum, it appeared that most folks who were lucky enough to latch on to one decided, like I did, that all the power wasn’t really necessary for knocking around in the woods and decided to tame it down with handloads. That also produced a shortage of what few jacketed .44 bullets were available at the time. So, the best option was to start casting bullets, or find someone who did, just to maintain a supply of ammunition. A problem showed up when the only cast bullet moulds available at the local outlet was the Lyman No. 429348 wadcutter that averaged 183 grains from my alloy(s). It was supposed to be a target bullet, but when launched at roughly 1,100 fps from the Hawes, it nearly cut big desert jackrabbits in half. Unfortunately, it punched big holes in prime coyote and badger hides. It also shot a bit low when shot from the Hawes with fixed sights, so the upper rear corner of the front sight was cut at approximately a 45-degree angle, the lower edge of which was used as a reference with the bottom of the rear notch to bring the relatively lightweight wadcutters to point of aim.

In time, while I maintained an interest in the .44 Special sixguns acquired over the years and adopted a .45 Colt for most outdoor work, .44 Magnum sixguns didn’t generate much interest, although there has been at least one in the safe for well over 40 years.

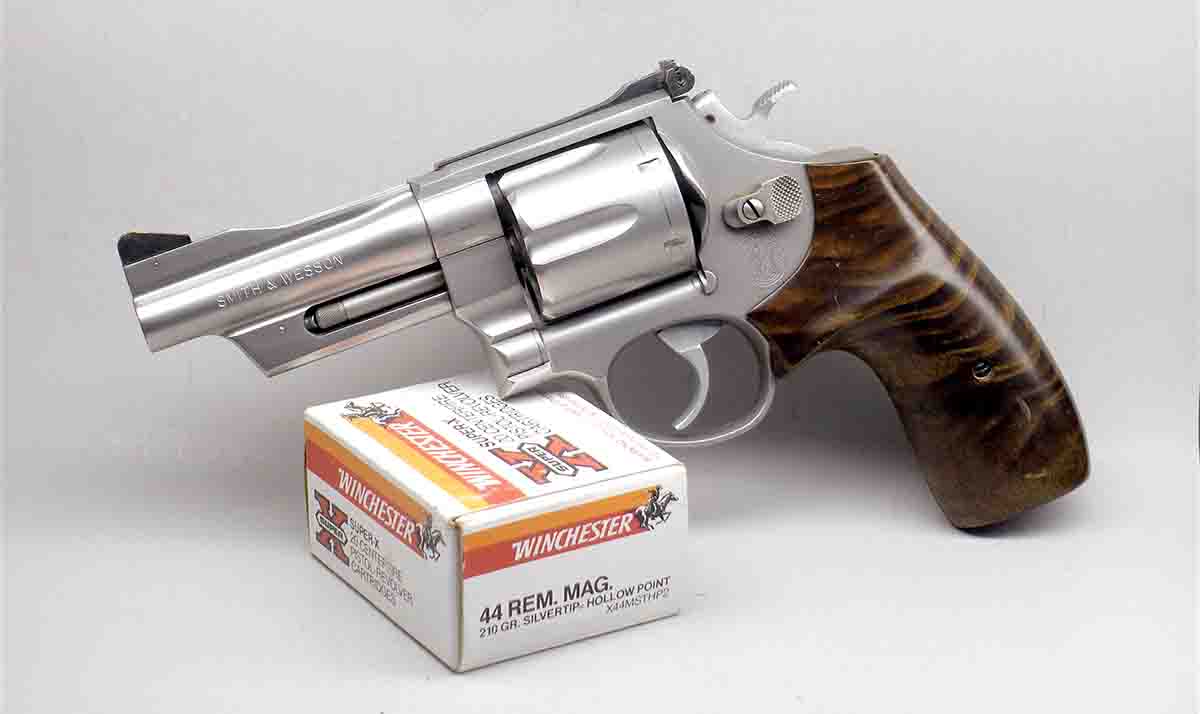

Interestingly enough, to date, my pet .44 Magnum is a pre-Smith & Wesson Mountain Gun with the typically tapered 4-inch barrel that lacks the later logo. With no improvements or alternations to the action, it is by far the most useful when compared to the big double- and single-action revolvers. Once it was decked out with Herrett Roper-type, round stocks, it handled perfectly with full-house factory loads or midrange handloads. If anyone had suggested I would someday prefer a relatively lightweight 4-inch Smith & Wesson .44 Magnum double action after shooting that first factory load in the Hawes nearly 50 years ago, I probably would have suggested they might want to exchange those chopped nuts they’re storing up between their ears for something a bit more useful.