Cartridge Board

.22 Long Rimfire

column By: Gil Sengel | April, 18

Chambering an expensive target rifle for a cartridge that pushed a 30-grain bullet maybe 700 fps seems absurd, but there was a reason. By the 1860s the growing popularity of target shooting with rifles was being held back by the 200- to over 1,000-yard ranges required, and all the paraphernalia needed for muzzleloading. The .22 rimfire changed all this. Ranges shrunk to 50 to 75 feet and even went indoors! All the ammunition and accessories needed for a day’s shooting could be carried in a jacket pocket.

Unfortunately, the S&W .22 was not enough of a good thing. As a black-powder round, it lacked the power to take small game at any but the closest ranges. Target shooters wanted more velocity, because sometimes bullets would stick in the bores of their long-barreled match rifles!

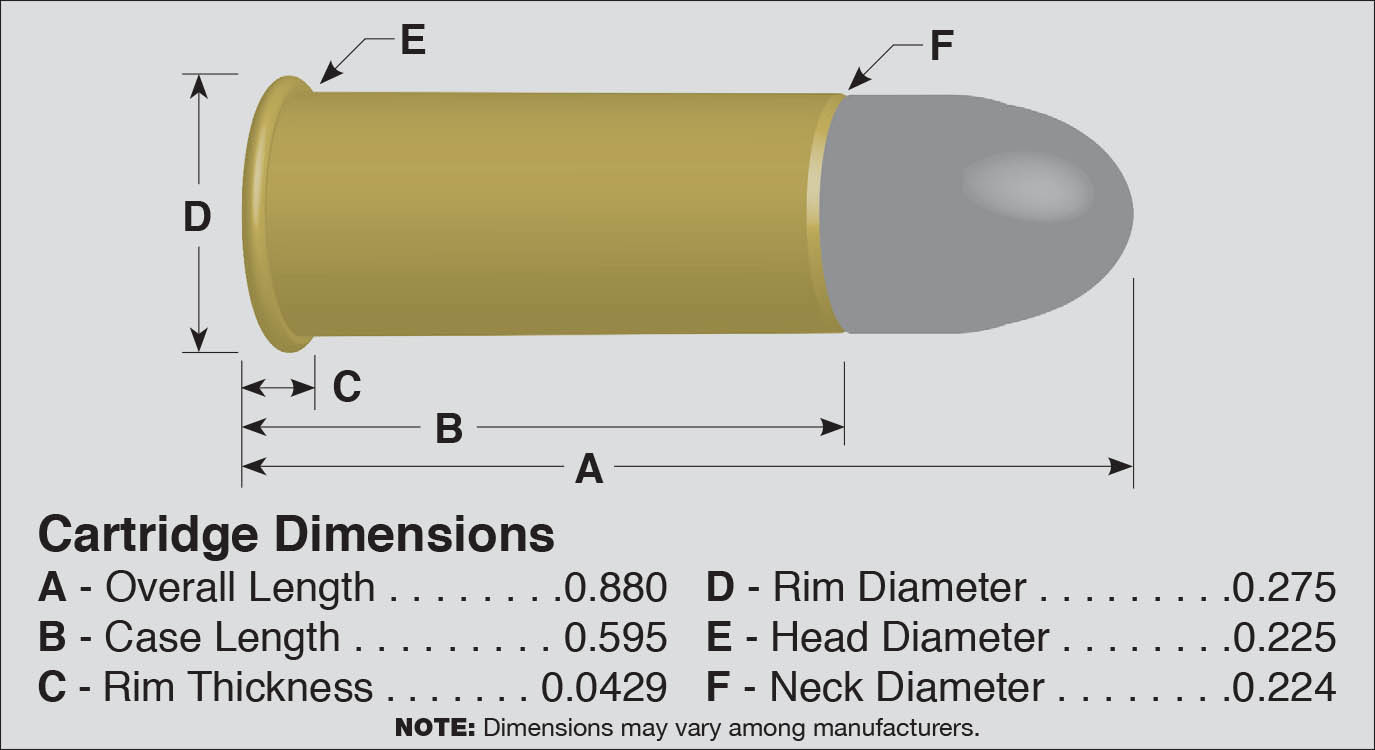

The solution to this problem was simple. A longer case was created that held 5 grains of black powder compared to Smith & Wesson’s 3 grains. The bullet remained identical in weight (25 to 30 grains) and shape to the shorter round. Early case lengths varied a bit, but basically the Smith & Wesson case was lengthened .2 inch to create the .22 Long. The earliest mention of the new cartridge appears to be the previously noted Frank Wesson rifles in 1868. Union Metallic Cartridge Company’s ammunition list of 1871 (its first) shows the .22 Long, but there were more than two dozen other early rimfire cartridge makers, any one of which could have had a hand in developing the new round.

Of interest is that an even longer case containing 7 grains of black powder and a 40-grain bullet appeared in 1878, called the .22 Extra Long. It was never popular. The .22 Long case was also used with a heavier bullet in 1889 to create the .22 Long Rifle, which likewise generated little general interest until the advent of semismokeless powder (a mixture of black and smokeless) became available.

Another fact is that the 30-grain bullet was retained for the .22 Long so that rifles firing the .22 Short could be simply rechambered for the Long; rifling twist was the reason. The Short’s 1:20 to 1:25 twist stabilized no bullet heavier than 30 grains.

Muzzle velocity of the early .22 Long is not known. In rifles it was probably 800 to 850 fps, and that depended greatly upon powder quality. Velocity went up a bit when smokeless and semismokeless powder loads began appearing about 1896. Then the early 1930s saw .22 rimfire velocities increase significantly; the .22 Long went from 950 to 1,025 fps in rifles to 1,285 to 1,400 fps, depending upon the manufacturer. Bullets included a 29-grain lead roundnose and 27-grain hollowpoint. All makers, however, still offered a “standard velocity” load at 1,000 to 1,050 fps because it sold well.

That’s as good as it got for the .22 Long. Target shooters had picked the .22 Long Rifle as their own and were chasing after greater accuracy from its 40-grain bullet. Ever more popular autoloaders fired the .22 Long Rifle only. By the 1960s just one load remained, a 29-grain roundnose bullet at 1,240 fps. Winchester dropped its cartridge in 1984, Federal about the same time, and Remington’s lasted until 1995. The mystery here is why a cartridge that was supposedly superseded by the .22 Long Rifle in the 1890s lasted another 100 years.

Chamber dimensions and scope sights then finished the job. As non-corrosive priming came online in the 1930s, rimfire owners saw less reason to clean their rifles. Bullet lube combined with unburned powder grains built up in the chamber until rounds would not go in easily. Autoloaders stopped autoloading. Gunmakers tried to deal with the problem by making the chamber a bit larger and the throat longer. The .22 Long bullet now had farther to travel to meet the rifling. Ever more popular scope sights showed the negative effects on accuracy. This was the death knell of the .22 Long. Well, almost.

CCI Ammunition (part of Vista Outdoors) has quietly produced a .22 Long for many years. Its bullet is a 29-grain roundnose at a published 1,215 fps. CCI also sells what the company calls a CB Long, which uses the same bullet at a reduced velocity of 710 fps for close-range pests. It is probably near the original black powder .22 Long. This ammunition gives an opportunity to gain insight into the old rimfire.

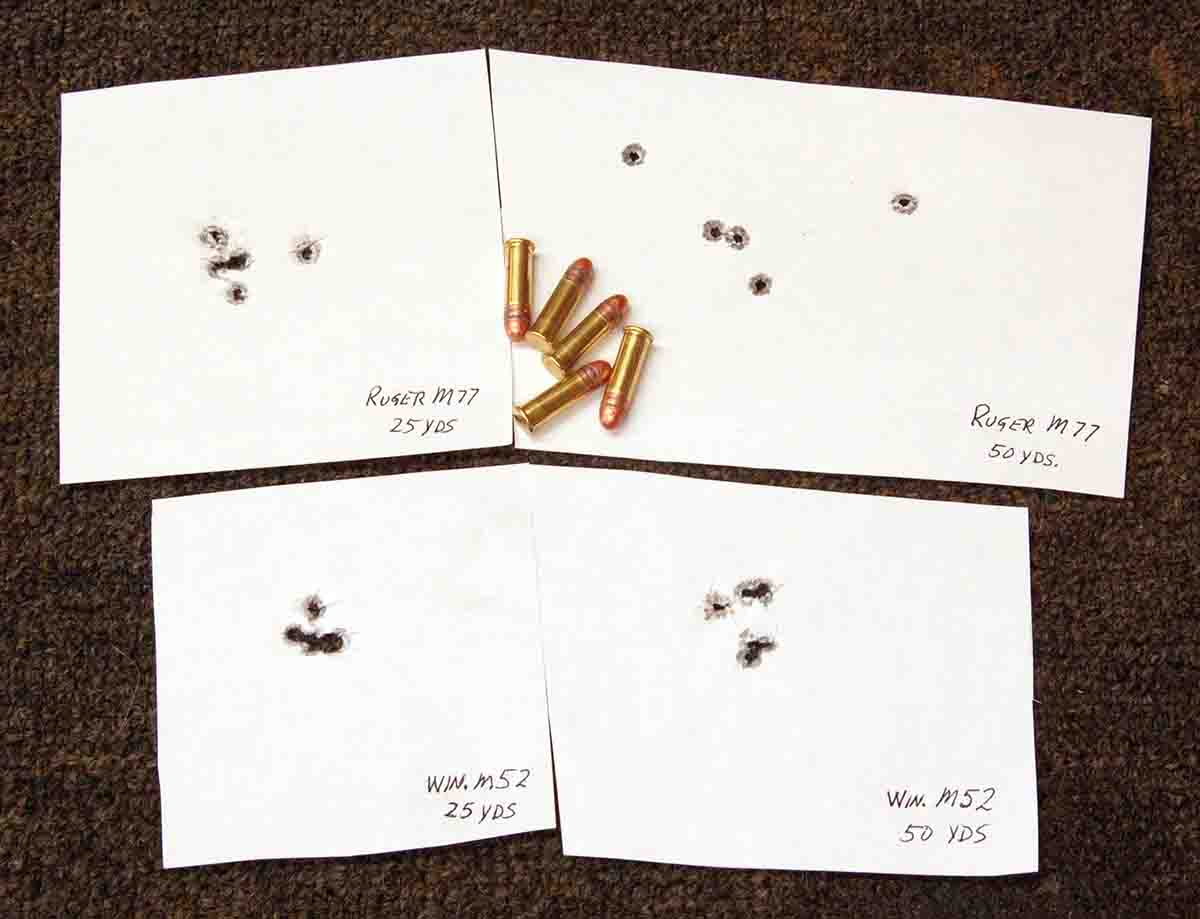

A Ruger M77 with modern chamber dimensions, 20-inch barrel and 4x scope was fired at 25 and 50 yards. Both CCI Longs and CB Longs gave half-inch groups, but a flyer out an inch or so was common. At 50 yards they would cluster into about 1.3 inches, with the errant shots out 1.6 inches. Muzzle velocity for 50 rounds of CCI Long averaged 1,252 fps; for the CB Long it was 762 fps.

The .22 Long had an 80-year run at being superior to the Short and cheaper than the Long Rifle. By WWII that changed, but CCI ammunition now offers fine accuracy when fired in a real match chamber. Many of today’s .22s are advertised to have match chambers. If that’s really true and not just bravo sierra generated by a marketing department, the Long still has a niche in the hunting field.