From the Ground Up

The Rise of the Nosler Partition

feature By: Terry Wieland |

The Nosler Partition was the first truly premium American hunting bullet, and even today it’s still in the top tier. If told that I could use nothing but Nosler Partitions for the rest of my hunting life, I would not feel at any disadvantage. Short range, long range, high velocity or low, big animals or small, the Nosler Partition is a bullet I know of that can be depended on to do the job.

Having said that, let me tell you about the only disappointment I ever experienced with a Partition. We were hunting Alaskan

For the next hour or so, we tried to find that first bullet, following the wound channel as far as a heavy chest bone, where the trail ended. It just . . . ended. We never found a single shard. My estimate is that it was traveling at close to 3,500 fps when it struck and was destroyed. But then, we could also have failed to find it in the tangle of long, wet fur, bear innards and my own jangling nerves. Frankly, I know of no expanding bullet ever made that would have done better, and after all, I did get the bear.

Incidentally, in my pocket at the time were some .300 Weatherbys loaded with 200-grain bullets, and back on our boat, a .375 H&H. When in bear country, I learned that day, a hunter should carry a bear rifle, regardless.

Over the course of 42 years hunting with Nosler Partitions, that is the only bullet that could even remotely be called a failure. In the years before and since, I have hunted Dall sheep, caribou, deer of various sorts, and a wide range of African game, and Partitions have always performed. Cartridges used ranged from the .257 Weatherby Magnum to the .375 H&H.

The operating principle of the Partition is simple: A copper alloy jacket is extruded in both directions, creating a forward and a rear cavity, separated by a solid retaining wall. These cavities are filled with lead. On impact, the bullet readily expands, almost regardless of velocity, but stops expanding when the partition is reached. The jacket folds back and the remaining slug – about 60 percent of its original weight – continues to penetrate. Typically, this slug is found under the animal’s skin on the far side.

The idea was not new. In Europe, RWS had for years loaded a bullet called the H-Mantle, which works on exactly the same principle. These, however, were rarely available in the U.S., unlikely to be found in preferred American diameters and bullet weights, and expensive if you found some. English gunmakers, too, had made use of the idea or something similar in years past. John Nosler, however, applied the principle to an all-American bullet and made them readily available to handloaders. He began with .308 diameter bullets of 150 and 180 grains, but soon expanded to such common calibers as .257, .270 and .284.

By the early 1950s, Nosler Partitions were on the market. In the 1955 Gun Digest, Elmer Keith reviewed the bullets then available as components and factory ammunition, and had this to say:

The best approach we have yet seen to the problem of a proper shaped spitzer, that will expand to long range and not blow up

Keith went on to write that he favored the Partition for all small-bore, high-velocity rifles for extreme long-range shooting of light game. He was absolutely right about the Partition’s future: For the next 40 years, it was the standard against which all big-game bullets were measured.

Looking at the construction of a Nosler Partition today, it seems simple and straightforward, but in the 1940s it was anything but. In his 2005 biography, Going Ballistic, written by Gary Lewis, John Nosler told the whole story of how he arrived at the principle but then had to overcome a seemingly unending series of difficulties getting it done. These included finding proper machinery and machining techniques, metallurgy of copper, lead and various alloys, and finding engineers and machinists. Finally, there was the difficulty of putting a complex bullet design into mass production in order to make it affordable.

In fact, Nosler spent a good portion of the early years teaching himself what he needed to know about engineering, because trained engineers knew little about what was required of a bullet – a problem that is not unknown today.

“My experience with engineers was that they didn’t know anything about bullets,” he said. “It takes a background with bullets to understand bullets.”

John Nosler was one of that extraordinary generation of postwar entrepreneurs who somehow managed to develop a product, learn a technology, run a business, deal with one technological problem after another, invent things as he went along and still manage to do a lot of hunting along the way. Where are those guys today?

In the end, the Partition was perfected, the product line expanded, and it began to establish a reputation. Elmer Keith, Warren Page and Jack O’Connor all admired Partitions. In particular, Page used almost nothing else in his 7mm Mashburn Magnum, with which he hunted all over the world, and wrote about at length in Field & Stream.

Initially, the Partition was purely a handloading proposition. When I first started using it in the 1960s, the company used a clever marketing ploy. At the time, most rifle bullets were sold in boxes of 100. The Partition was more expensive to manufacture and cost twice as much as Sierras or Speers. Instead of packing them 100 to a box and displaying a price twice

The Partition did not just reach perfection and remain unchanged forevermore. As different manufacturing techniques were used, so did the bullet evolve in small ways. Some of these were noticeable. Early Partitions that I bought had what appeared to be a square-edged cannelure aligned with the solid partition. This was put there, according to Nosler, to allow the partition to pass through the barrel without pressing on the rifling. This feature was later dispensed with.

Almost from the beginning, the Partition was a prestige product. Nosler established a relationship with Norma, the Swedish company that manufactures ammunition for Weatherby. To the best of my knowledge, Norma and Weatherby were the first to offer factory-loaded Partitions at a higher price. Norma later offered Parti-

tions in its own ammunition as well, and from there the practice spread throughout the industry. Aside from improving Nosler’s cash flow with volume orders to Norma and others, it cemented the Partition’s reputation as a premium hunting bullet.

Not surprisingly, there were a few bumps in the road. A few hunters of my acquaintance claimed they found differences in performance between Partitions of different eras. In the 1980s, some insisted that the jacket alloy was harder and more brittle, and the bullets were not performing as well as they had in the past. If that was indeed a problem then (and I never saw any evidence of it myself), it is not a problem now.

Another criticism was the discontinuing of some diameters. As the product line expanded, one bullet that established an excellent reputation was the 300-grain .375. For a period in the 1980s, it was discontinued, then reintroduced. Exactly what the reasons were I have never been able to ascertain. Bullet companies tend to be very tight-lipped, not only about their processes, but about the reasons behind such actions. One can hardly blame them because one misinterpreted statement, or a comment taken out of context, can stay in print and multiply through the years, haunting them forevermore.

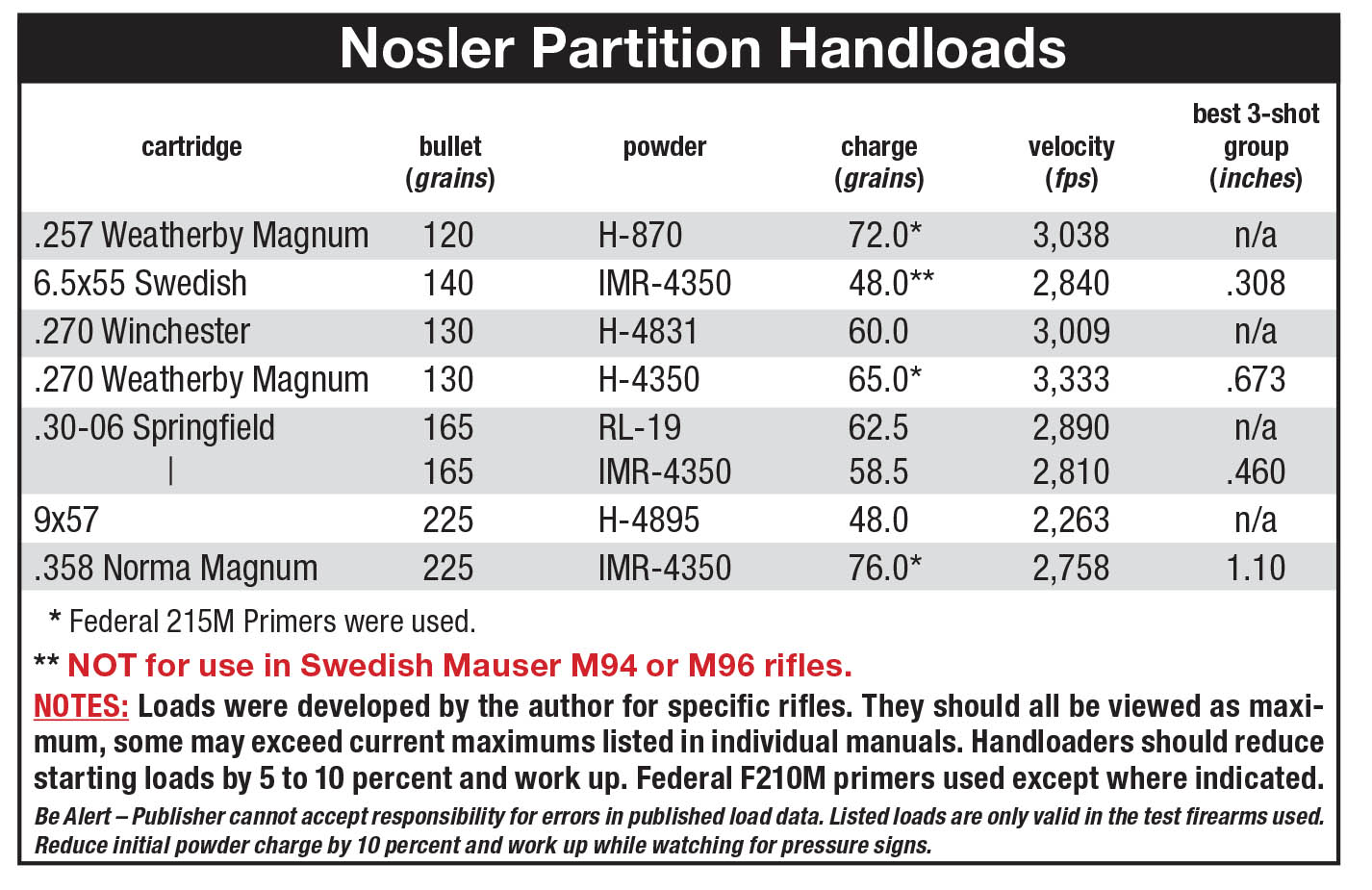

The single best three-shot group I ever fired from a hunting rifle was with a custom Weatherby Mark V, .270 Weatherby Magnum, shooting factory 150-grain Partitions. It measured .248 inch. The rifle never shot such an extraordinary group again, but it was always very accurate, and I took a bull elk with it in Montana in 2012. In 1990, a Parker-Hale Model 1100 Lightweight 6.5x55 Swedish developed a liking for 140-grain Partitions. Its best three-shot group measured .308 inch, and I used it to take a Dall ram on a Chugach mountaintop later that year.

Going through files, I find that I have fired several outstanding groups with Partitions from quite a variety of rifles. Aside from the two above, there was a group measuring .673 inch from the same .270 Weatherby using 130-grain Partitions, and one at .460 inch using 165-grain Partitions in a Dakota .30-06.

The success of the Partition was partly responsible for the flurry of premium-bullet developments in the 1980s and 1990s, and while most focused on bonding lead cores, one of the best – the Swift A-Frame – used both bonding and a copper cross member through the center of the bullet to create one of the best all-around game bullets now available.

Today, the Nosler company has diversified considerably, not only in its bullet designs, but in the production of rifles and premium ammunition. The company is still producing the Partition, though, and it’s still one of the best-performing and most accurate game bullets out there – all thanks to one tough moose, back in 1946, that flatly refused to go down.