Reloader's Press

A Half-Century of Cast Bullets

column By: Dave Scovill | April, 18

Over the years, it has been interesting to observe the change in interest regarding handgun bullets. In the early 1970s, cast bullets appeared to be of primary interest to handloaders, both in revolvers and semiautomatics. Currently, most of the interest appears centered around jacketed bullets, likely paralleling the rising popularity of progressive reloading machines that tend to clog up somewhat when fed a steady diet of lubricated cast bullets. Either way, during the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was rare to come across a handgun feature in the gun press lauding jacketed bullets of the day. Experts seemed to agree, for maximum handgun performance in the field, cast semiwadcutters were the soup du jour.

As it turned out, two .44 Specials were located in a pawn shop, a Smith & Wesson Second Model Hand Ejector and a Colt Single Action Army. The owner of the shop tossed in a box of Remington factory loads to boot. The next task was to locate one of those bullet moulds everyone praised, Lyman’s Keith-type No. 429421 SWC.

There was also an outfit in San Francisco, California, Markell Cast Bullets, that sold the Lyman bullets sized and lubricated. The catalog stated they were cast from Elmer Keith’s alloy, one part tin to 16 parts lead. I ordered 500.

A quick trip out to the high desert proved Skelton was right; those roundnose .44 Special slugs weren’t much better than the 158-grain .38 Special factory loads. One rangy rabbit absorbed three of those .44 slugs at ranges from 25 to 70 yards before it rolled over. The next trip to the desert with the Markell cast bullets loaded over 7.5 grains of Unique proved Skelton was right on that point as well.

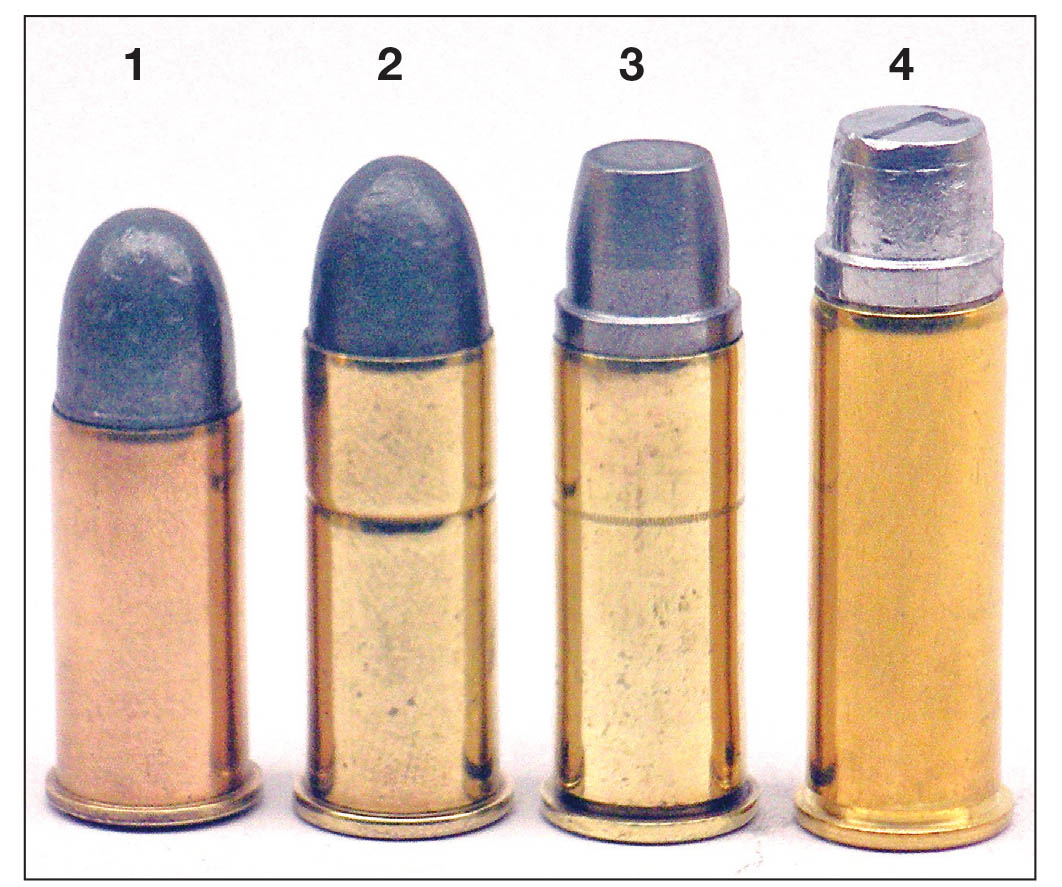

A couple of years prior to finding the .44s, a Colt SAA .38 Special was located in Oregon, used for a few years and converted to .45 Colt with a 7.5-inch barrel. Even with factory loads, the .45 was a bit of a thumper, and an order was placed for a supply of Markell Lyman Keith-type No. 545424 SWCs sized to .454-inch. Several powders with various charges were used, but the final load that produced accuracy at least as good as the .44s consumed 16.5 grains of 2400, or in those days, 15.5 grains of now long-gone W-630.

As most folks were aware at the time, the .45 Colt was problematic, mostly owing to oversized chamber throats and post-World War II .451-inch barrel diameters. That was, of course, in contrast to the relatively new and much stronger Ruger Blackhawk .45 Colt that came out in 1971. Smith & Wesson then introduced the 125th Anniversary Model .45 Colt with its short cylinder and oversized chamber throats that also turned out to be problematic when the Lyman/Keith bullet had to be seated to crimp over the forward edge of the first driving band, or the cases shortened.

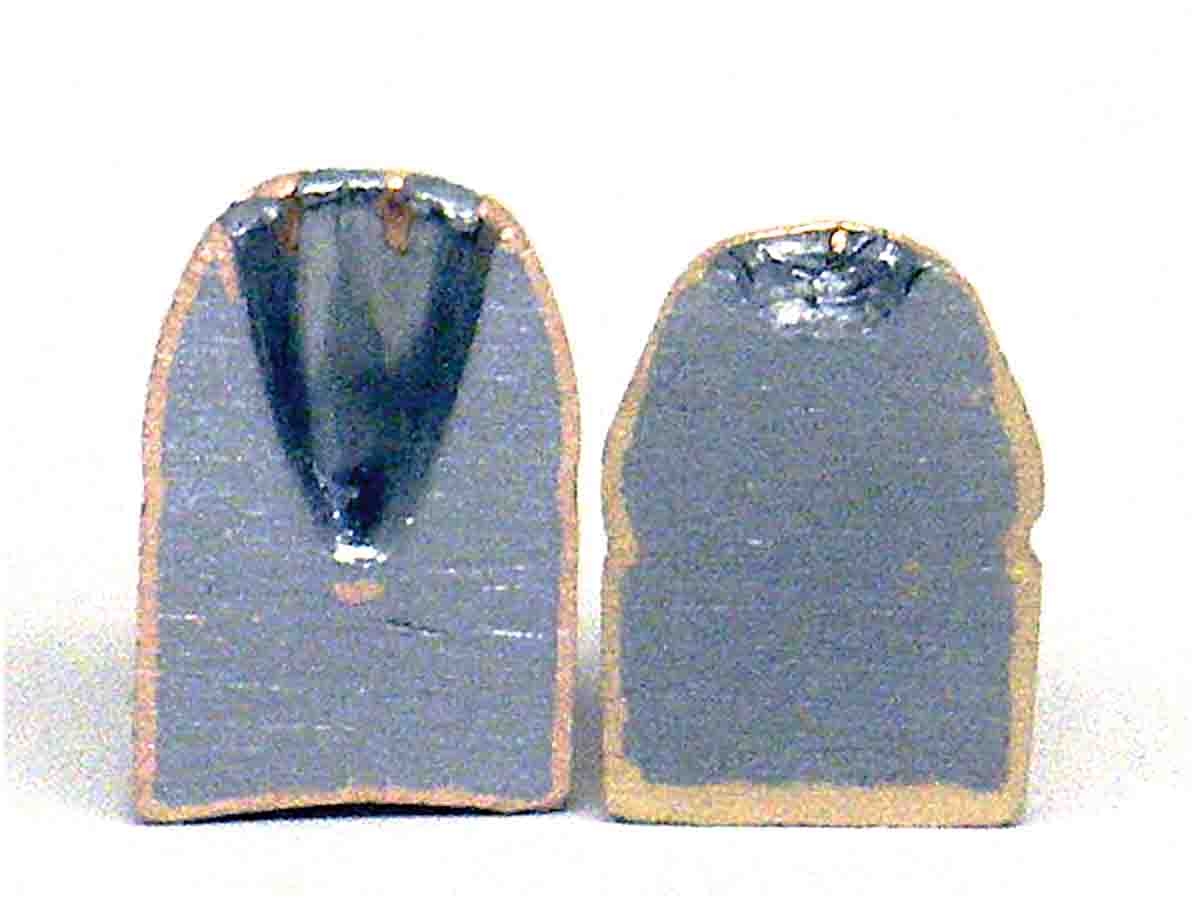

Of course, there were jacketed bullets available in those days, but for the most part they failed to expand at sixgun velocities. Even the Speer half-jacketed semiwadcutter and/or hollowpoints behaved like monolithic solids where impact velocities in a bundle of wet newspapers were much below 900 fps or so. The best of the lot in terms of accuracy were the Hornady .45 Colt 250-grain pre-XTP jacketed hollowpoints, but they too behaved like solids in small game and/or coyotes. Sierra also developed some good .44- and .45-caliber bullets, but overall, jacketed handgun slugs were a poor substitute for good cast semiwadcutter loads, albeit they did a fairly good job when pushed to maximum velocities in .357, .41 and .44 Magnums, or in souped-up loads for the Ruger Blackhawk .45 Colt.

Speer also had a lineup of swaged lead semiwadcutters in solid and hollowpoint form that were coated with some sort of moly-based lubricant. They could-n’t be pushed much over 900 fps in .38-, .44- and .45-caliber barrels, but with good loads they provided yeoman service. A few years back, Speer improved the coating somewhat by making it slightly thicker and more durable, allowing somewhat higher velocities sans barrel leading.

The 158-grain, .38-caliber Speer slugs are available in solid or hollowpoint, and the larger calibers are solid semiwadcutters. A similar coating is applied to Speer hollowbase wadcutters. The entire lineup is quite suitable for most outdoor chores for folks who want the security of a handgun or a good bullet for plinking or target loads. The best part, possibly, is they shouldn’t clog up the bullet tubes on progressive loaders, the popularity of which may have brought about the improved coating more recently.

Many years ago, if someone had said jacketed bullets are more accurate than cast bullets, I may have believed them, but after nearly 50 years of shooting cast and jacketed bullets in a variety of calibers, it appears to be more of an old wives’ tale. Not long ago I fired 50 rounds of 240-grain cast bullets (.430-inch, BHN 10) at 115 paces with a Colt New Frontier .44 Special from an improvised rest. The powder charge was 13.5 grains of Alliant 2400. I missed the 12-inch gong 14 times, mostly low and left, but the barrel and forcing cone were nearly spotless after the last round was fired.

The purpose of that exercise was to verify a load I had been using for more than 40 years with a new batch of cast bullets from a lot of 500 ordered from Rim Rock Bullets (www.rimmrockbullets.net) that shot as well as expected before taking it into the field. Of course, the misses are important as well, and are usually the result of crowding the frame with the trigger finger, which hardly affects accuracy at 25 yards or so, and may go unnoticed. So relatively long-range testing not only tests accuracy, but it also reveals flaws in shooting technique as well.

Back in the late 1970s, that .44 Special load was used to shoot (at) silhouettes on the Black Canyon Shooting Range (now Ben

In the “take it for what it’s worth” department, for folks who may be concerned about handling lead alloy bullets or fumes from casting, I have had well over a dozen blood tests in the last 30 years, not counting those taken by the U.S. Navy while on active duty. None have revealed any signs of lead poisoning, in spite of over 45 years of casting bullets. That is likely because I use a fan to blow fumes from the casting pot out a nearby door in the garage or outside during warmer months. Of course, leather gloves are standard while casting, so there is no reason to handle freshly cast bullets with bare hands until they are handled during sizing, lubricating and seating in the case neck, where mechanic gloves may come in handy.