11.15x51R Kurz

Reinventing a 140-Year-Old Cartridge

feature By: Terry Wieland | December, 19

Only when I got it home did I look at it really closely. It’s built on an early Martini action probably dating from about 1880. The bore, what I could see of it, looked to be about .44 caliber. The buttplate was loose, it was missing the adjustment screw for the double-set trigger, and from all appearances it had not been cleaned in a century. Getting the initial repairs took me to Lee Shaver’s shop in Lamar, Missouri; for information on German Schützens, he referred me to Bill Loos in New York, one of the authors of Alte Scheibenwaffen, a three-volume, 1,198-page, 14-pound tome on the entire

Most of the historical information found here originated with those books. Like Alice following the white rabbit down its hole, I had no idea what I was getting into. The rifle is a true Martini, which is significant because the Germans made several dozen variations on it in the period between 1880 and 1935. The only name is “A. Gesinger, Bremen” on the barrel, but he was most likely the retailer, not the maker, and there was no suggestion of what the caliber or chambering might be. It’s quite plain by Schützen standards, but (as can be seen) very photogenic and extremely well made.

There are more such rifles in the U.S. today than anywhere except Germany itself, most of them brought back by returning soldiers in 1945. Because traditionally the detachable sights were stored separately, many of these rifles lack them altogether; and because the sights were usually custom to the rifle, finding replacements is not as easy as checking on eBay. This rifle, fortunately, had the tang (diopter) sight and a

Apparently, German target shooters used all three simultaneously, with the diopter serving not as an aperture sight but as an optical aid to sharpen the sight picture of the mid-barrel and front sights. Bill Loos found an old sight in his collection that could be made to fit, however. Lee made the alteration and the rifle was fully sighted and ready to go. This sounds quick but it took several months altogether.

That left only (!) the ammunition question. The first step was to slug the bore; the second was to make a chamber cast. Under the grime, the bore proved to be .440 caliber or, in European parlance, 11.15mm. The chamber cast was less conclusive. As

Bertram in Australia makes .43 Mauser brass, imported by Huntington Die Specialties. Having obtained a supply, I began cutting it down until I got a workable case that did not stick in the chamber.

Bullets, oddly, were no real problem: Bob Hayley has a mould he had custom-made some years ago to duplicate the original U.M.C. bullet for the .43 Mauser, .43 Spanish and similar cartridges. It’s a roundnose with a hollow base, weighing 370 grains. Redding volunteered to make dies if I could provide some fired cases

The base of the .43 Mauser case is oddly shaped by modern standards. It has a rim, but the base itself is convex, so it fits no standard shell holder. Having determined that 2 inches was a good length, I cut some cases, trimmed the mouths and seated primers using a vise. The first time, I crushed the case mouth before the primer was fully seated, so I used a piece of steel rod in the vise to push against the web from inside rather than exerting pressure on the thin brass of the case mouth. This was slow, but it worked fine.

Ron Reiber at Hodgdon advised that a reasonable starting load would be 28 to 30 grains of 4198, either Hodgdon or IMR. With 30 grains, the cases were sticky, so I backed off to 28 grains. By using bits and pieces of other die sets, I managed to cobble together three shootable rounds and sent the cases off to Redding. A month later, a set of dies

According to Alte Scheibenwaffen, there were literally dozens of different but very similar cartridges extant during the 1880s and ’90s with, it seemed, every gunsmith offering his own variation on a theme. Since Schützen shooters would obtain a supply of brass, then load their own at each match, a continuing supply of factory ammunition was not a big concern. The diameter (11.15mm) helped to pinpoint its likely year of origin. Just as American target shooters progressed from .44 to .40 to .38 to .32 from the 1880s to 1900, Germans went from 11.15mm down to 10.4, then 9.5 and finally settling on the 8.15 after 1893. My rifle being an 11.15, I figured it was made around 1880, and that fits with its Martini action as well.

Like many German Martinis, the rifle was built to allow easy take-down without tools – although, as I found out, this does not necessarily translate to easy reassembly. To dismantle it you ease the lever down to take pressure off the main spring, remove the pivot pin holding the breechblock in place and lift it out the top of the action. The entire lower section, including the trigger group, can then be removed by pivoting a lever on the tang 90 degrees. It must be done in that order, and the lower section must be replaced before the breechblock. Even then, there’s a trick to it. Once you get it down, however, it’s remarkably easy.

The trigger is a three-part double-set trigger, standard on high-quality rifles of the time, but some gunmakers provided triggers with up to seven leaves to achieve an almost supernatural degree of sensitivity.

The stechermachermeister (master trigger maker) was a recognized specialty in the German gun trade, and these specialists worked on their own, providing custom trigger groups to gunmakers large and small. The triggers were beautifully made of the finest materials available, and they work astonishingly well. Both Frank de Haas (Single Shot Rifles and Actions) and James J. Grant (Single-Shot Rifles) stated categorically that German set triggers were the best in the

The bore of the rifle was a mess, but repeated applications of lead remover, Hoppe’s No. 9 and finally ultra-fine valve-grinding compound revealed a bore with clean, sharp rifling, although there is some visible roughness.

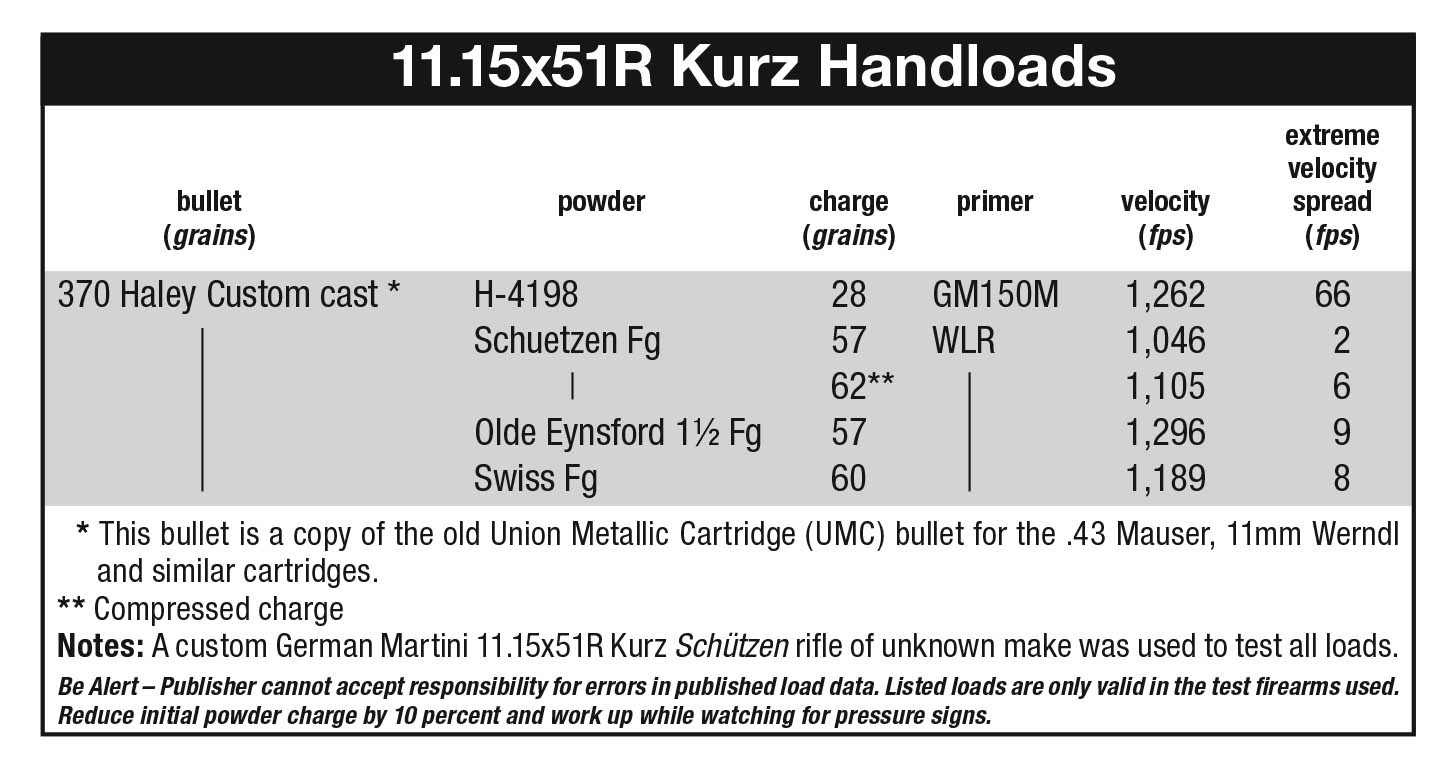

Since it was originally intended for black powder, I tried a variety (see table) with decidedly mixed results. A straight load of Schuetzen Fg gave remarkable consistency but low velocity. Duplex loads gave higher velocity but wild variations. Given the results, there seemed little point in pursuing duplex loads. A greater compressed load of Schuetzen Fg accomplished little. Swiss Fg and Olde Eynsford 1½ Fg both gave higher velocities, but with more variation.

As the barrel fouled – which it did alarmingly quickly – accuracy dropped off to nothing, by which

The twist rate is 1:20, and the bullet is 1.1 inches long, so even at a velocity as low as 1,050 fps, it should be fully stable. When the bullets did hit the paper, as far out as 200 yards, there was no suggestion of keyholing. My conclusion was that the roughness of the bore combined with severe fouling to deform the bullets enough to throw them off course. As soon as the bore was clean, the bullets began to fly true once again. Incidentally, I noticed no difference in the level of fouling whether I was using straight black powder or the duplex loads. It was all bad.

The 370-grain bullet has a hollow base, allowing it to expand to grip the rifling similar to a Minié ball, so it is not dependent on black-powder ignition to bump it up to bore diameter. However, the fouling could have been tearing at the bullet’s skirt, which would not help.

But (and to me it’s a very big “but”) the old rifle is fully functional, fitted with proper sights with all its little ills corrected and shooting reliably once again. It is also attracting admiring (or at least curious) glances from everyone who sees it. We should all do so well when we hit 140.