.222 Remington Magnum

Modern Powders and Bullets for an Old Classic

feature By: Mike Venturino | December, 19

About the time this is printed I’ll be celebrating the fortieth anniversary of buying my first and only .222 Remington Magnum rifle. It is a sporter weight Remington Model 700 ADL in pristine condition that was at a gun show in Great Falls, Montana, and it was a present to myself for my thirty-first birthday. At that time my shooting passion was to try every varmint cartridge from .222 Remington to .25-06 Remington – almost, but not quite accomplished.

An obvious question is: “Why did Remington follow up with a magnum version of its already popular .222 Remington?” That first one was introduced in 1950. With the longer version of the .222 the company didn’t even bother with the magical belt around the case head so identified with rifle cartridges labeled “magnum.”

Here is a brief synopsis of how matters played out back in the 1950s. The

At the end of World War II, the Soviet’s Red Army captured the Sturmgewehr’s designer, Hugo Schmeisser, and took him to Mother Russia for a full decade. In the late 1940s the Soviet Union then introduced its wood and steel, select-fire AK47 chambered for a full caliber (albeit shorter case) round named the 7.62x39mm. Firing from a 30-round, detachable, curved magazine, AK47s were certainly not light rifles at 9½ pounds. Soon manufacture segued to stamped steel, which reduced weight about one pound.

U.S. weapons designers decided to do the Soviets one better. Their idea was to reduce rifle weight with a synthetic stock and aluminum parts, and reduce ammunition weight by reducing caliber from 7.62mm (.308 inch) to 5.56mm (.224 inch). Initial tests were with the .222 Remington, but it was deemed under-powered. The military wanted to use a 55-grain FMJ bullet with which the standard .222 could hardly break 3,000 fps from 20-inch barrels as envisioned for the new rifle.

Next was an experimental round labeled “T65.” It was simply the .222 Remington stretched from 1.70 inches to 1.85 inches with most dimensions identical and shoulder angle remaining

Therefore, the case was remodeled to 1.76 inches in length; again with most other dimensions the same, including the 23-degree shoulder angle. Here is where most comes into play. Case neck length for the standard .222 was .313 inch; for the T65 it was reduced to .264 inch, and for the final version, the U.S. 5.56mm, neck length was shortened even more to .203 inch. Did that help with full auto functioning? Or was the shorter overall case length of 2.26 inches for 5.56mm compared to the T65’s 2.28 inches a factor? No matter, for the 5.56mm was chosen and with greatly different bullets is still standard for U.S. armed forces.

Back to the T65: Remington knew a good cartridge when it saw it and in 1958 added it to the company’s line-up as the .222

Then the roof collapsed on both the standard and magnum .222s. It has always been an American truth that a cartridge adopted by our armed forces automatically becomes popular in the civilian sector. In 1964 Remington introduced a civilian version of the 5.56mm, calling it the .223 Remington. It doomed both prior .222s.

After buying my .222 Remington Magnum, a friend came into a Remington Model 722 so chambered, but with a shortened barrel. Memory is dim, but I think its barrel was only 20 inches long. In the early 1980s I provided a comprehensive article for Handloader on the .222

Actually it doesn’t matter, for the one thing definitely remembered is my favorite load. It consisted of Speer 52-grain HPs over 24.5 grains of Hodgdon H-322 with Remington 7½ Bench Rest primers. Velocity ran between 3,150 fps to 3,200 fps. A few years ago when loading .222 Remington Magnum ammunition, I discerned that most of my cases were failing. Many cases necks had split and most primer pockets were loose. I toyed with the idea of having the barrel set back and rechambered for .223 Remington. Fortune sometimes smiles on people. A friend for whom I’ve done favors came into a sizeable batch of once-fired .222 Remington Magnum cases, which he generously shared with me.

Another factor that has changed greatly since I wrote that first .222 Remington Magnum article early in the 1980s is propellant choices. I have a Lyman Reloading Handbook 45th Edition dating from the 1970s. Only 33 smokeless powders are listed in it. In the early 1980s Lyman Cast Bullet Handbook 3rd Edition there are 37 selections. Now hold onto your hats! The most recently printed reloading manual I have is dated 2016. It’s Lyman’s 50th Edition Reloading Handbook and 127 smokeless powders are listed in it. For sure a bunch more have been introduced in the last three years.

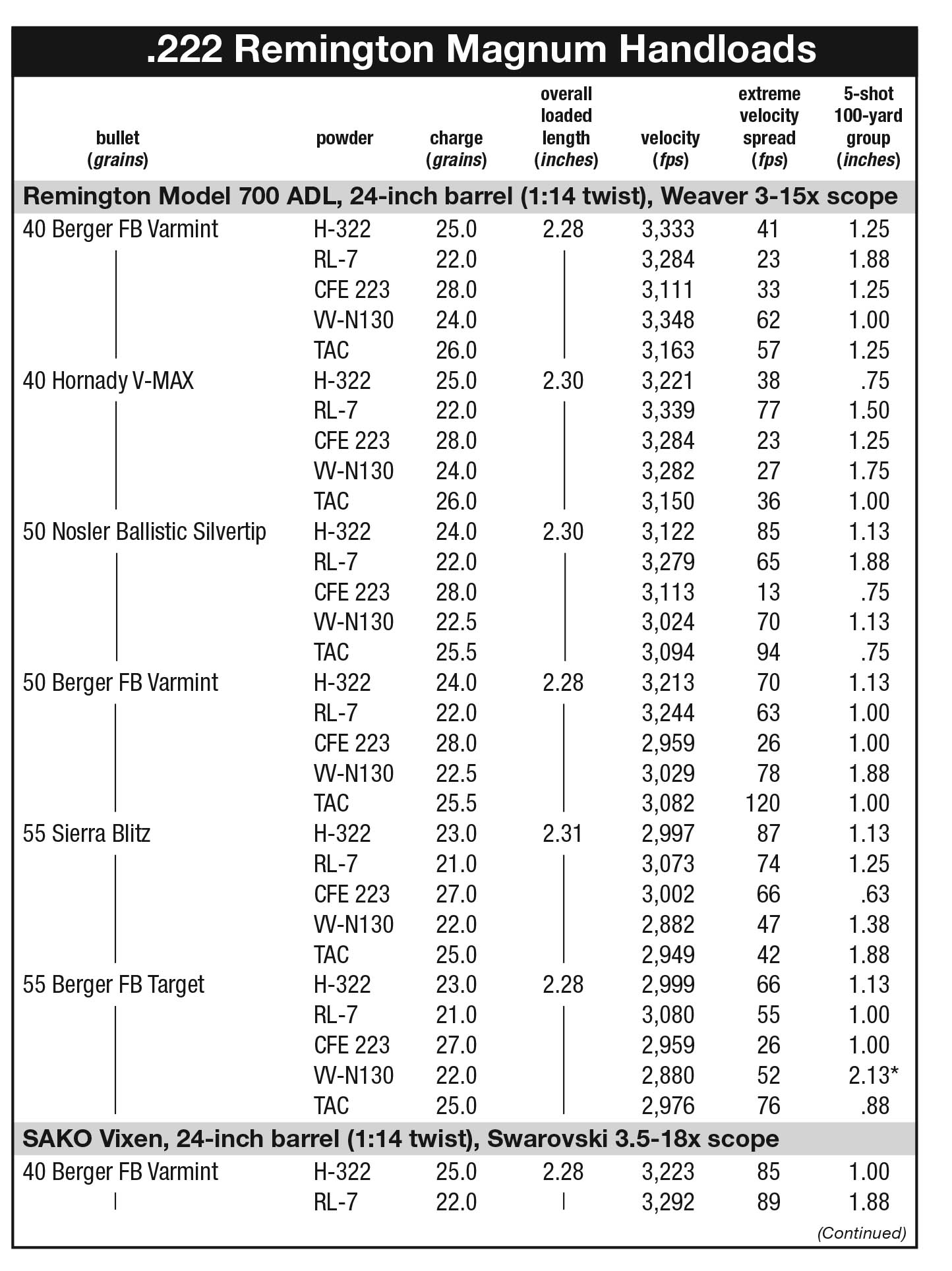

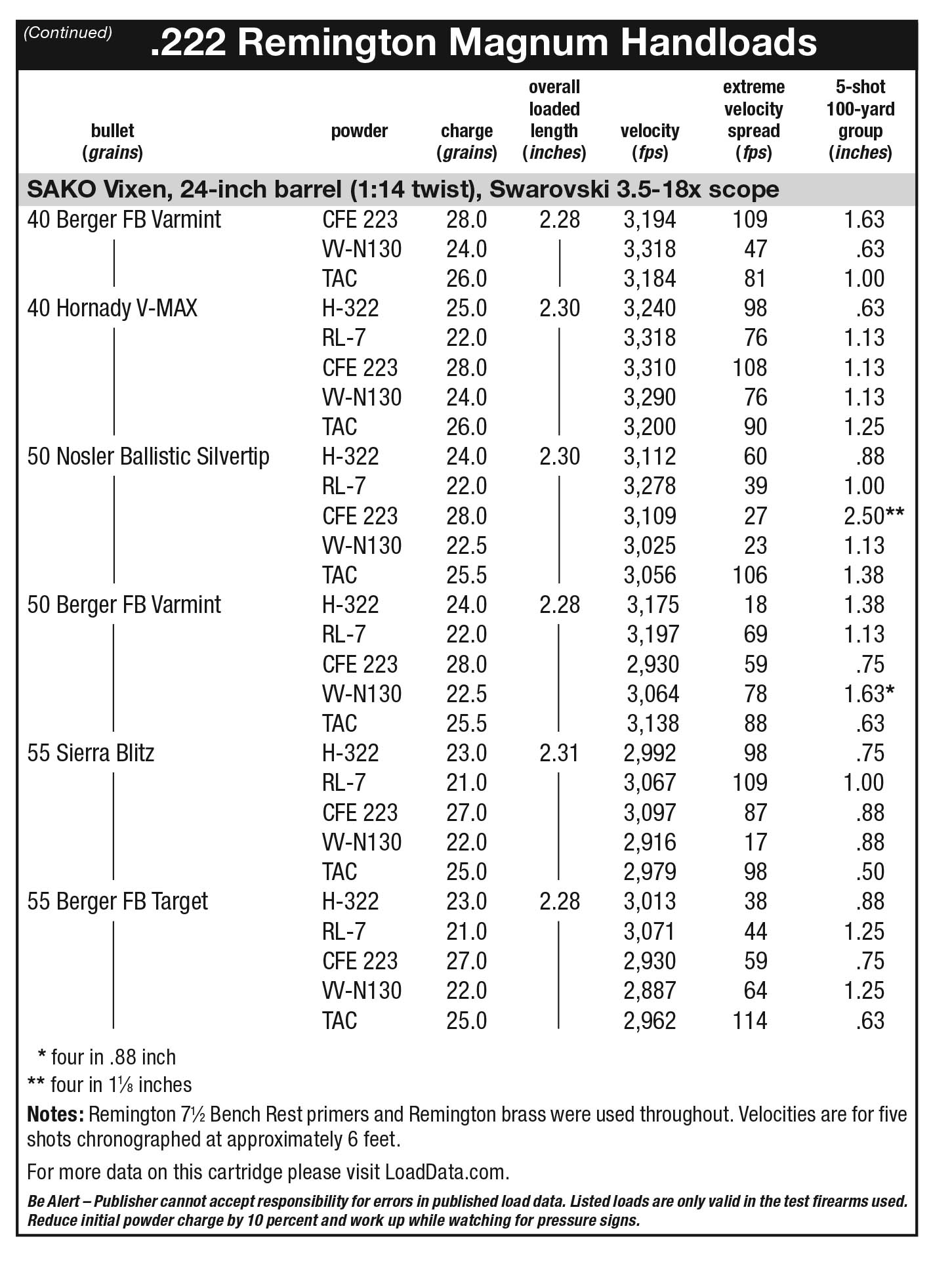

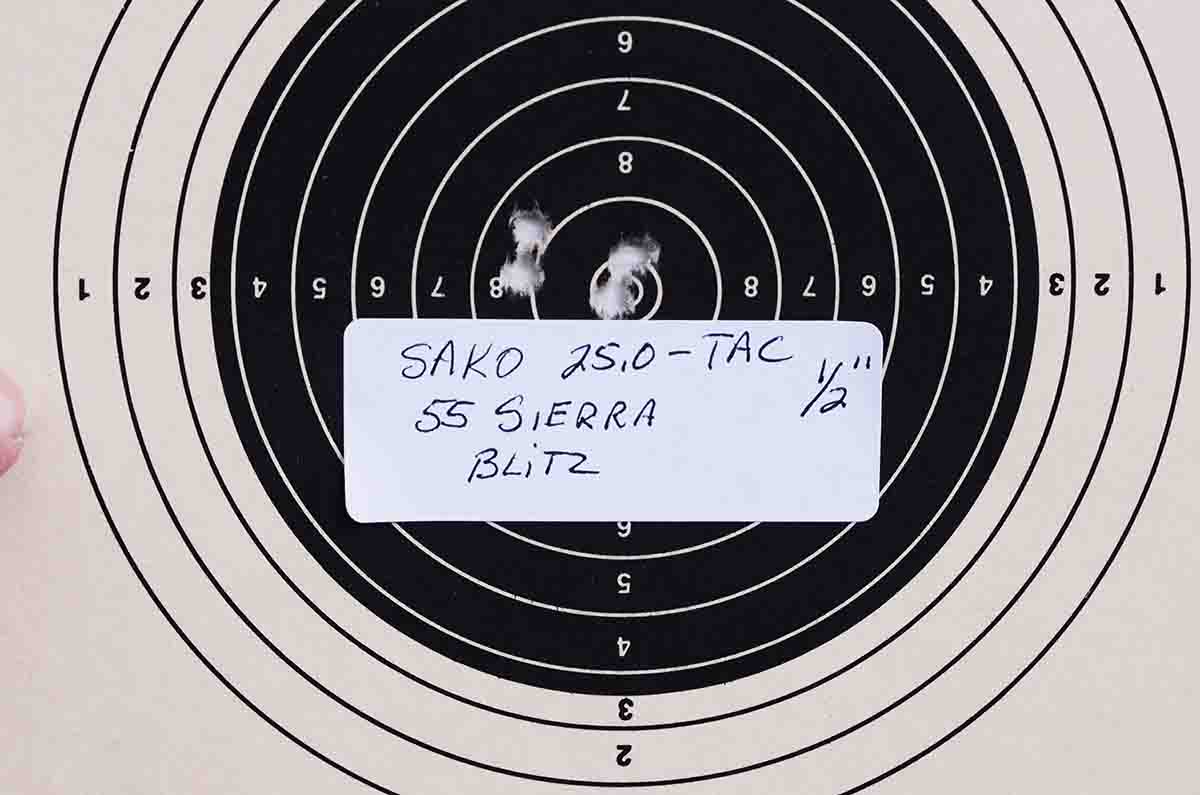

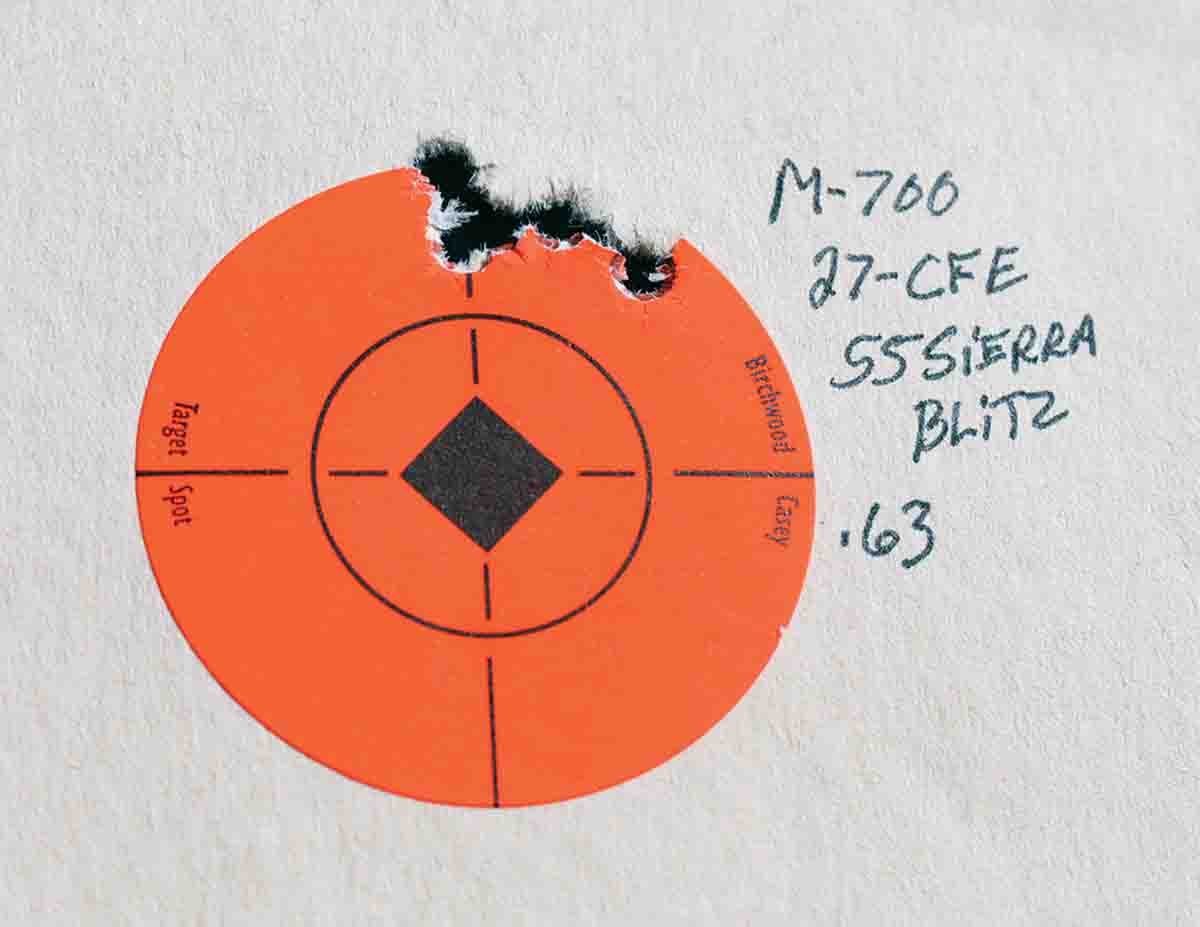

My Original plan was to only shoot my own Model 700 for this project, but a friend then offered his heavy barrel SAKO Vixen topped with a Swarovski 3.5-18x scope. Both rifles have 24-inch barrels with 1:14 twist rates. My M700 wears a Weaver Tactical 3-15x scope.

At each outing both rifles were fired with the same loads to keep velocity readings as consistent as possible. However, shooting all 60 groups (30 each rifle) required several months because Montana’s 2019 spring weather was uniformly miserable. Shooting was done at temperatures as low as 32 degrees and up to 68 degrees. All group shooting was done in five-shot strings at 100 yards.

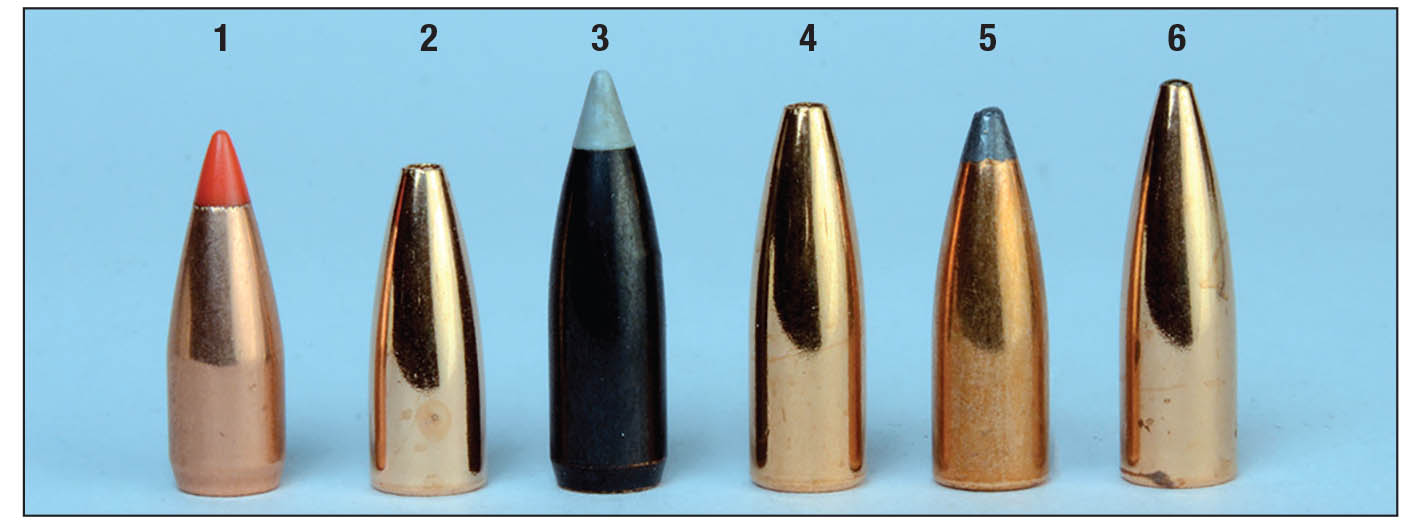

Looking back on the results, I’m glad we did include two rifles. From each rifle’s 30 groups a trend seems to appear. The SAKO on the whole gave a tad bit smaller groups than the Remington. However, if a load gave large groups with one rifle, it usually did so with both rifles. For instance, with Berger 40-grain HPs and Reloder 7 the Remington gave a 1.88-inch group and a 1.75-inch group from the SAKO. Conversely, with Berger 50-grain HPs and CFE 223 the group sizes were 1.00 and .75 in the same order.

Speaking of velocities, my helpful friend was surprised that on the whole the velocities given by all test loads were “low” in his opinion. For instance, the highest velocities with either rifle were in the 3,200- to 3,300-fps range, even with light 40-grain bullets. He asked why I didn’t increase charges. Mostly I could not because there was not enough room in the cases for more powder unless it was heavily compressed. My opinion is that extreme velocity is not paramount with a round the size of the .222 Remington Magnum. It’s a moderate-range varmint cartridge anyway. If a long-range varminter is required, a .22-250 Remington or .220 Swift would serve better. A moderate- range varmint shooter would be best served by tight groups.

After charting and examining all the chronograph notes and measuring each five-shot group, I can say that my old friend H-322 did not embarrass me, but Ramshot TAC was arguably the star performer.

There is no way the .222 Remington Magnum is going to undergo a resurrection. Waves of varmint shooters are not going to scream for reintroduction of factory loads or new rifles so chambered. But, for those of us who do own rifles for this fine old cartridge, there is no reason to let them sit dusty in racks.