Learn To Reload (Handloading Basics)

Load Development

feature By: John Haviland | December, 19

Current handloading manuals help expedite the process. Manuals that sell for about $30 contain handloading information that required years of research and untold thousands of dollars of expense. The manuals discuss the construction and intended uses of projectiles, which is a great aid in choosing bullets. For instances, the Nosler Reloading Guide 8 contains general descriptions of all Nosler bullets and includes the minimum and maximum “optimum performance velocity.” Appropriate bullet choices are listed for each cartridge. In the load data section, powders that provided the best accuracy are highlighted. New bullets and cartridges are continually introduced and many websites, such as load-data.nosler.com, federalpremium.com/reloading and Wolfe Publishing’s LoadData.com contain up-to-date reloading data.

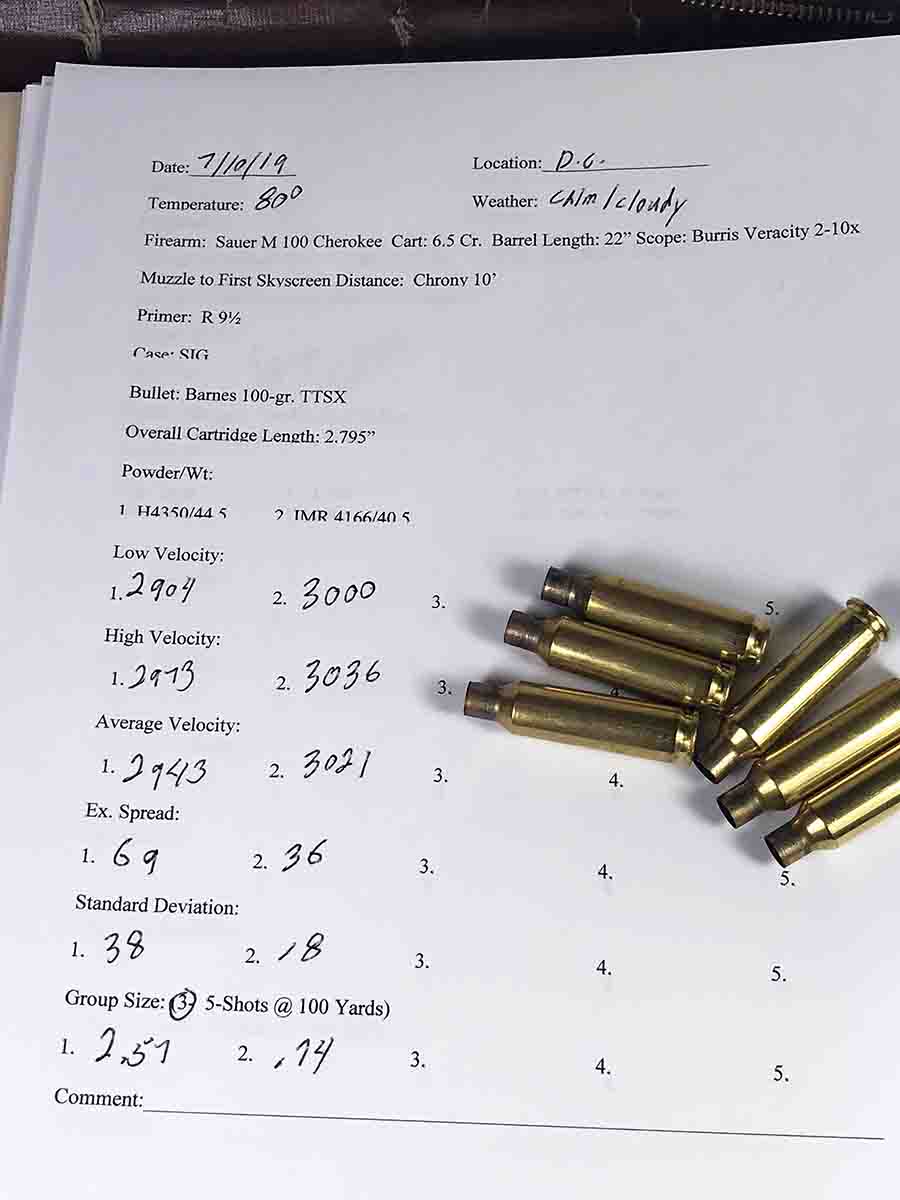

Keeping Records

“The weakest ink is better than the strongest mind” may or may not be an ancient Chinese proverb. The adage certainly pertains to handloading, because without records to consult it’s difficult to know where you are going if you don’t know where you’ve been. When I started handloading as a teenager, I wrote a load’s particulars on a cartridge box and let it go at that. Of course, the information was eventually lost and I had to start over from scratch.

The amount of bullet drop at those ranges can also be entered into a ballistics program to closely determine the muzzle velocity of a load’s bullets. In the program, enter exactly where bullets hit vertically at 100 yards and keep changing muzzle velocity until the program’s trajectory meshes with your results.

Picking Powder Charges

In the past, the method of perfecting a load was to pick a low starting charge of powder and increasing its weight in small amounts. As shooting progressed, an eye was kept on the appearance of the fired cases for signs of excessive pressure, such as flattened primers or firing pin indents with a raised (cratered) perimeter or a shiny mark on the face of the case head. Resistance to opening a rifle’s action was another sign of undue pressure. When those signs appeared, powder weight was reduced a grain or two – and the powder charge called “maximum.” The problem is those pressure warnings fail to appear until well after maximum pressure has been exceeded.

For instance, the Reloader’s Guide at alliantpowder.com lists only the 60.8-grain maximum charge of Reloder 26 for Nosler 150-grain Partition bullets loaded in the .270 Winchester. A prudent handloader should start with a powder charge at least five percent below the listed maximum. I started with 57.5 grains of Reloder 26 and worked up to 60.5 grains that fired Partition bullets at 3,042 fps from the 24-inch barrel of a Mossberg Patriot Revere .270 Winchester. However, that load developed too much pressure fired in a Montana Rifle Company .270, which resulted in flattened primers and stiff bolt lift.

Hodgdon’s maximum powder charges range from .4 to 1.0 grains lighter than listed in the Speer book. That difference could be explained by Hodgdon using Winchester cases and a 1.155-inch cartridge overall length compared to the Federal cases and

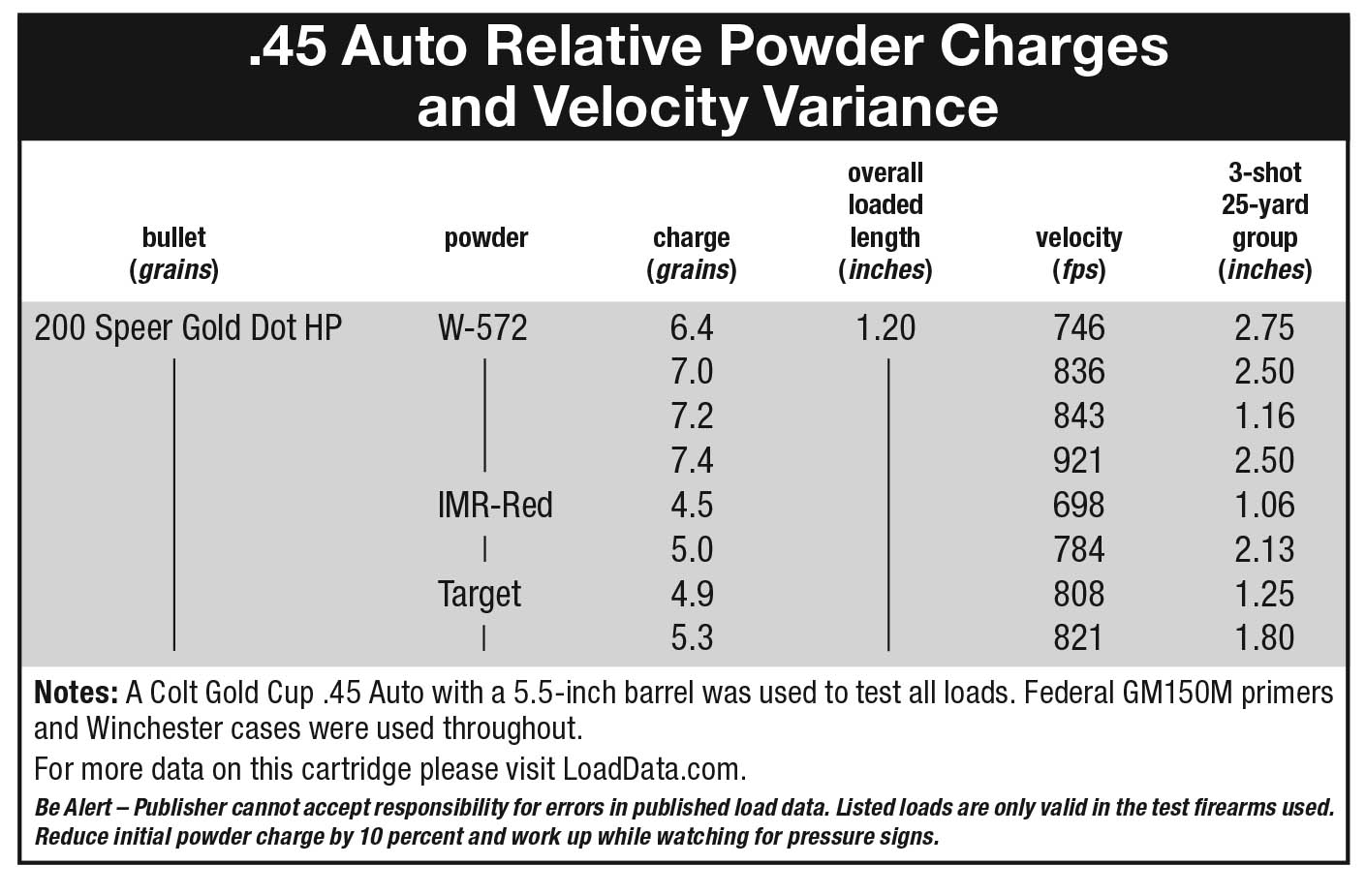

I picked Winchester 572 as a full-power load for the Speer bullet for carrying the Colt along mountain trails, and IMR Red and Target for a slightly slower velocity for target practice.

The three powders with Federal GM150M primers were loaded in Winchester cases, starting with Hodgdon’s stated minimum loads and working up in small increments. The table on page 69 shows the results from the Colt’s 5.5-inch barrel.

Winchester 572 charges were increased .2 grain as they neared maximum. The boost from 7.2 to the maximum 7.4-grain charges increased velocity 78 fps. IMR Target could have been boosted another .6 grain and IMR Red .5 grain to maximum. Accuracy was the best, though, at the two powders’ lowest charge weights.

If different charge weights of a certain powder fail to provide expected accuracy and velocity, move on to another. If your pocketbook allows, testing several powders at once saves time. I tried five different powders with Hornady 75-grain V-MAX bullets when working up a load for a Cooper Model 22 .243 Winchester to agonize marmots. The V-MAX bullets shot fine with all five powders. Benchmark was the winner, though, with two three-shot groups that measured .64 inch at 100 yards, 1.12 inches at 200 yards and another .64-inch group at 300 yards, which might have resulted from some luck.

Attesting Accuracy

How many shots are required to verify a load’s worth? Are three shots enough? How about five, seven, 10 or several series of shots? At some point, shooting ability is tested as much as the gun and load. I load three cartridges to start, especially when increasing powder weights. Firing that many shots does not reveal a load’s true accuracy, but shooting three bullets does

Bullets tend to wander some from aim as the barrel heats up from firing more than three .30-30 Winchester cartridges from my Winchester Model 94 Legacy. So it’s a waste to fire more shots to test loads. The Winchester is set aside until its barrel completely cools before firing it again. The same three-shot drill goes for my Ruger M77 .338 Winchester Magnum. Not that bullets drift as the barrel heats up, but because I have never shot more than that many bullets at one time at a bear or elk. Along with testing loads, I am also confirming that cartridges fit and feed from the rifle’s magazine and that the rifle’s scope maintains its setting against recoil.

However, I might shoot my Savage Model 10 .223 Remington 100 or more times at ground squirrels during a day. One load created for that shooting consists of Berger 50-grain FB Target bullets paired with 26.5 grains of Ramshot TAC and CCI BR4 primers in Remington cases. Five of the bullets had an average muzzle velocity of 3,192 fps and a 38-fps extreme velocity spread. The five bullets formed a pleasing .65-inch group at 100 yards. Wondering if that good performance would hold up, four additional five-shot groups were shot. The size of the four groups averaged .73 inch with an average velocity of 3,191 fps and a 28-fps extreme spread, very close to the results from the first five shots. Those 20 additional shots should have been saved for ground squirrels.

Refining Loads

Once the sweet scent of burning powder has drifted away on the breeze and a reasonably suitable load has been created, a load can be further refined by switching primers and altering bullet seating depth.

Primers are the last component to change when perfecting a load. I’ve never seen an improvement in accuracy from a revolver or pistol shooting match primers, like Federal Gold Medal, compared to regular small or large handgun primers. However, an accurate rifle can benefit from experimenting with different primers. I recently loaded CCI BR4 Bench Rest and CCI 450 Magnum Small Rifle Primers with Benchmark powder and 50-grain bullets in .223 cases. Groups shot with BR4 primers were half the size

Bullets seated a certain distance from touching the start of the rifling can help a load shoot its best. Finding the optimum distance to seat bullets from the rifling leade requires some shooting and is mostly limited to bolt-action and single-shot rifles with some leeway for cartridge length. Still, all rifles have chambers of slightly different dimensions and various amounts of wear to their rifling. Cartridges with bullets seated to a specific length that fit and shoot accurately in one rifle might shoot poorly or even jam a bullet into the rifling of another rifle chambered for the same cartridge.

Cartridge length listed for a specific bullet in handloading manuals is a good place to start. Sierra bullets generally shoot accurately when seated to the cartridge length suggested by Sierra. The Berger Bullets Reloading Manual 1st Edition lists only a cartridge’s established maximum length for all the company’s bullets.

While developing and testing various loads for my .243 and .223s involved a lot of expense and work, the effort of tailoring loads was enjoyable, informative and ultimately satisfying.

[John Haviland’s “Learn to Reload” six feature series spans the last six issues of Handloader, From No. 318 to No. 323. Back issues are available online at wolfeoutdoorsports.com or by calling 800-899-7810. – Ed.]