Cartridge Board

.44 S&W Special: Modern Day

column By: Gil Sengel | December, 19

Then there was the power factor. Early smokeless powders were temperature sensitive and produced much higher breech pressures than the old powder. Black-powder velocities could not be safely duplicated with the smokeless then available – and couldn’t be for several years. Use of black powder was so prevalent that in 1934 Winchester still listed 26 different revolver loads fueled by the old powder, including the .44 Special.

Another question is how can a cartridge fired in a revolver with a barrel that has a .420-inch bore and .429-inch grooves be called .44 caliber? Caliber is a bore

Finally, why didn’t S&W just chamber the Triplelock for .45 Colt and forget a new cartridge? This was mainly because of extraction problems caused by the .45 Colt’s tiny rim when used in guns with “star” extractors that removed

all six fired cases at once. This was no problem with the Colt Single Action, which pushed empties out one at a time. Then there was the ever present gripe that the .45 Colt kicked too much for quick, accurate shooting. It seems like people who actually shot the gun, rather than just carried it around, were the source of such observations.

Smith & Wesson was well aware of all of this and simply lengthened the .44 Russian case to create the .44 Special. It was a good plan, as it quickly became obvious that, as with the .32 S&W Long and .38 S&W Special, the company produced another winner. Colt even quicly chambered its large frame revolvers for the new cartridge.

Nothing changed until 1925 saw a smokeless round added in which a metal cap covered the 246-grain lead bullet’s nose only. Its purpose was stated as giving police a round with greater penetration in automobile bodies because bad guys were increasingly using cars to escape capture.

At the same time, the “wonder nine” (high-capacity 9mm autoloader) craze was beginning and would see law enforcement abandon the revolver. Over the span of about 20 years the .44 Special revolver became unwanted, even though its ammunition continued to sell to magnum owners. Some suggested the gun could be used for home defense, but consideration must be given to over-penetration. The big bullet is not much impressed by a couple layers of sheetrock!

By this time only one .44 Special round was still available, a smokeless cartridge using a 246-grain lead bullet at 755 fps – exactly the same as in 1918. There was, however, a bright spot in the picture. I believe it was 1981 (I don’t have this catalog) when Federal Cartridge introduced a 200-grain semiwadcutter hollowpoint for the .44 Special listed at 900 fps from a 6.5-inch barrel. It was intended as a self-defense load for abandoned revolvers and the new Charter Arms .44 Special Bulldog. Interestingly, the 1982 catalog shows the bullet seated to less than maximum .44 Special overall cartridge length. In 1983 it was seated out where it should be, minimizing jump to the rifling and certainly improving accuracy.

Winchester announced a 200- grain Silvertip hollowpoint at 900 fps in 1983 and a 240-grain lead Cowboy Load at 750 fps in 1999. These are still available, as is the 246-grain roundnose load of 1907! Remington lists only the latter. Hornady shows a couple .44 Specials. One contains a 165-grain FTX bullet leaving a 2.5-inch barrel at 900 fps. The other uses the 180-grain XTP at 1,000 fps from a 7.5-inch barrel.

The .44 Special is the same powerful handgun cartridge it was in 1907, but the country that introduced it has changed. There are simply far better choices for hunting. As for defense, six shots may not be enough. Autoloaders in 9mm or .40 S&W are easier to control and hold at least twice as many rounds.

Owners of the old revolvers need not be despondent. The guns seem to be gaining a status. Hopefully, increasing prices will prevent people from using handloads hotter than the revolvers were designed for, thus ruining them for future owners. The observation, “If you want .44 Magnum ballistics, buy a .44 Magnum” applies here.

Best of all, the .44 Special is the Number One handloader’s and bullet caster’s handgun cartridge. Small defects in cast slugs don’t seem to make any difference in accuracy. Varying crimp, bullet hardness, the bullet itself and even bullet lube, however, can lead to impressively small groups in unabused guns.

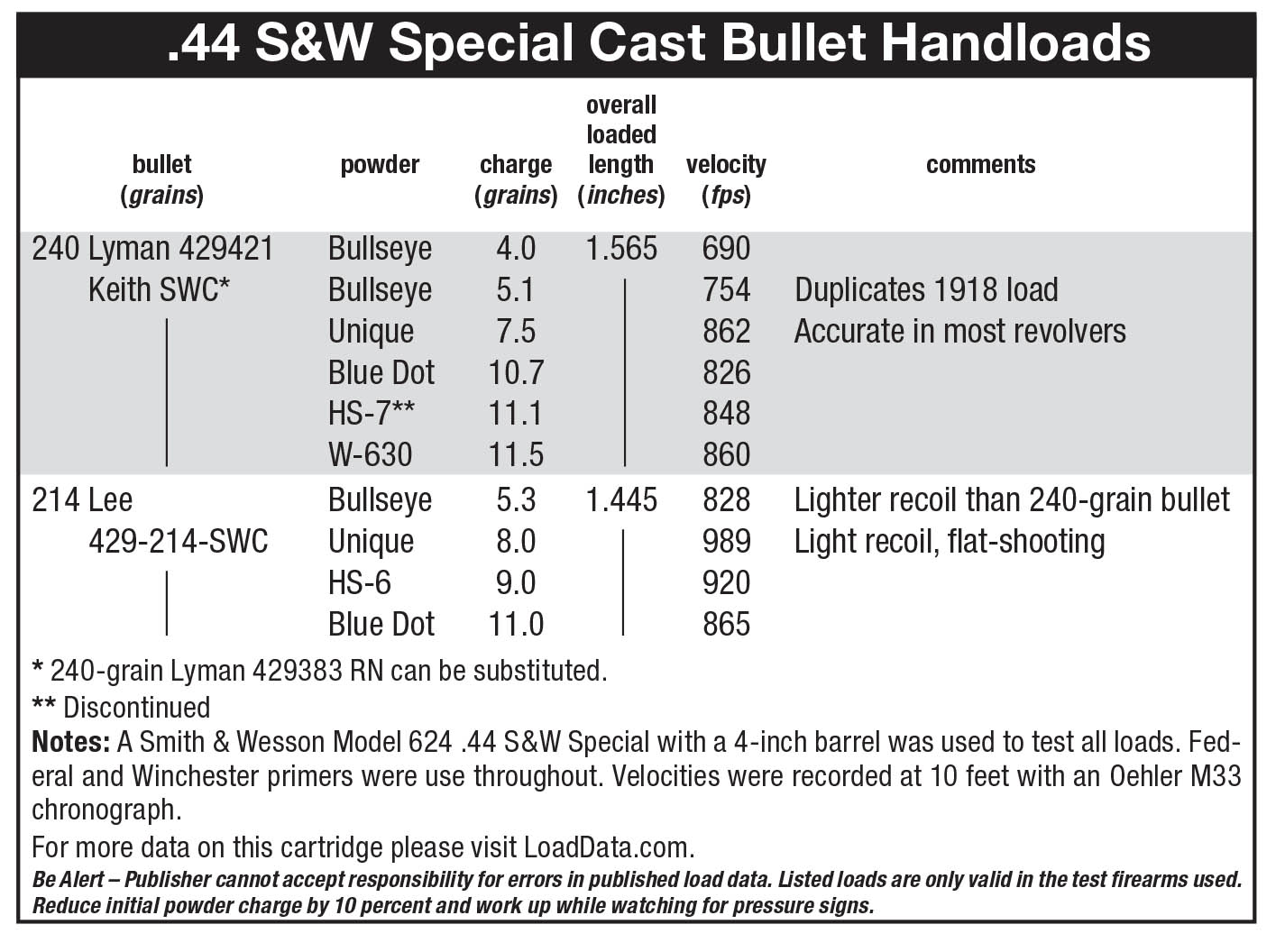

The two S&W Model 624s shown were prettied-up because each will put a cylinder-full of cast bullets into 1.5 inches at 25 yards over sandbags. Not spectacular accuracy, but good enough to hit pop cans and tip-over targets out to 50 yards or so. Accompanying load data is from the 4-inch revolver. Powders are well-known favorites always stocked by local dealers.

Because of the .44 Magnum, the .44 Special has remained the same cartridge it was when introduced in 1907. This is a good thing.