Wildcat Cartridges

7mm TNT

column By: Layne Simpson |

When deciding to join in on the fun I could shoot a match at a different range every Saturday of each month without driving more than 75 miles from home. In the beginning, competitors were searching for the ideal cartridge and quite a few were shooting the Remington XP-100 pistol in .221 Fireball. It shot flat, churned up very little recoil and was quite accurate, but even with the Speer 70-grain bullet loaded to primer-popping pressures, the little cartridge often failed to topple over those pesky 50-pound steel rams.

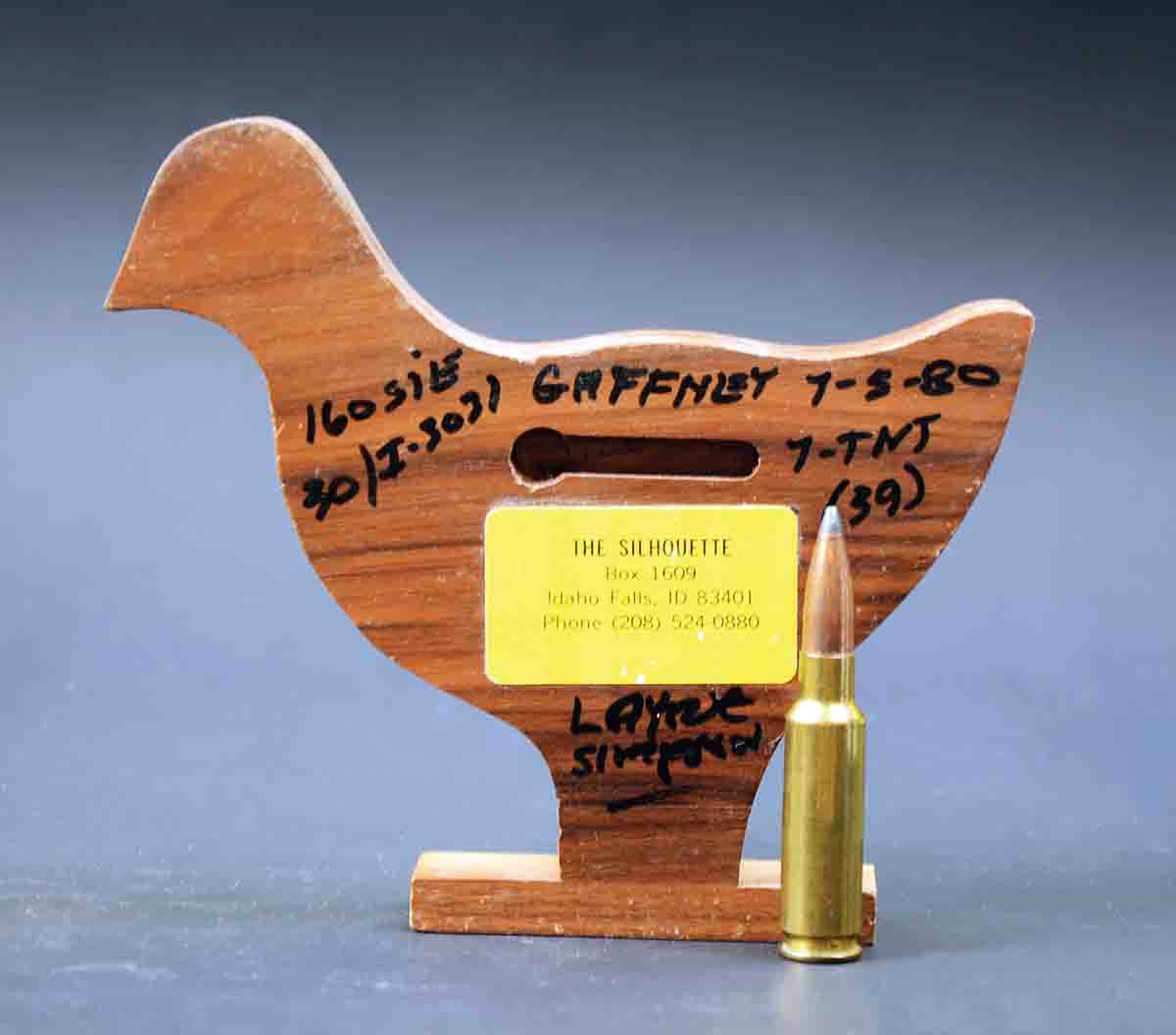

Most shooters who were new to the game usually started with factory Remington XP-100 or Thompson/Center Contender pistols. Having very little interest in those guns at the time, I jumped into unlimited class with a custom gun built on a highly-modified XP-100 action by New Hampshire gunsmith John Towle. Back then I traveled a lot each week by automobile, and prior to shooting my first match I practiced in motel rooms by dry-firing at scaled-down paper targets taped to the wall. It obviously paid off because on July 5, 1980, I shot a 39x40 in my very first match.

Not having shot a handgun silhouette match in over 30 years, some of the rules back then have become a bit fuzzy. As I recall, maximum weight for an unlimited gun was 72 ounces, and the factory XP-100 with a 15-inch barrel in 7mm BR qualified mainly because of a thin barrel measuring .565 inch at the muzzle.

When building his silhouette pistols, Towle removed as much weight as possible from the XP-100 action and, it left with a 15-inch barrel measuring .830 inch at the muzzle. The bolt was “Swiss-cheesed” to the extreme and with the exception of the receiver ring, the top and bottom of the receiver were machined flat. While writing this I dug out my digital postal scale. The bolt weighs 6.8 ounces compared to 11.2 ounces for a factory-original XP bolt. The complete barreled action weighs 59.2 ounces and the fiberglass stock weighs only 9.6 ounces. At 68.8 ounces, the pistol was inside the maximum allowable weight with enough cushion to compensate for a bit of variation in scales used by match officials at various clubs. Scopes were not allowed in those days so the gun features a fully-adjustable Bomar rear handgun sight and a Lyman Globe rifle sight up front.

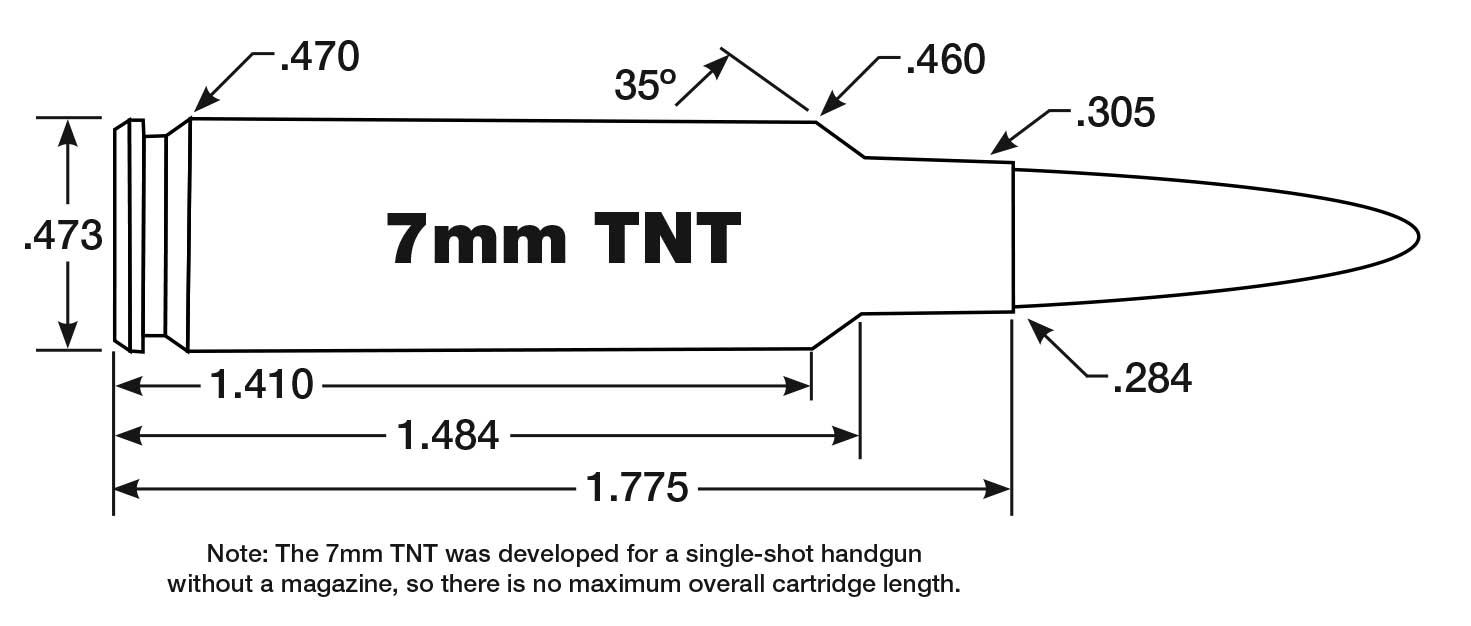

Mine is chambered for the 7mm TNT, but the .270 TNT and .300 TNT were also available. Towle recommended forming cases from Remington .308 BR brass, which was a .308 Winchester case pocketed for small rifle primers. He preferred that case because more beef in the web allowed many firings before an expanded primer pocket sent it to the scrap bin. The BR case was the same length as the standard .308 Winchester case but it was intended for forming the short 7mm BR Remington, so its body wall was thinner. Average gross capacity for the 7mm TNT case formed from BR brass

My pistol came with RCBS case-forming and reloading dies. Running a case through the first form die pushes the shoulder back, increases its angle to 35 degrees and leaves a long neck approximately .300 inch in diameter. The second die squeezes the neck on down to 7mm and holds the case for shortening with a hacksaw and squaring up the mouth with a fine-tooth file. A trip through the full-length resizing die readies a case for loading. No fire-forming was required; I simply loaded the cases and started banging steel.

Remington stopped making .308 BR cases years ago, but Starline and Lapua offer .308 Winchester cases with small rifle primer pockets. The Starline case is head-stamped “.308 Match” rather than “.308 Win.” Another option is to form cases from Starline and Lapua 6.5mm Creedmoor cases with small primer pockets. The thicker body walls of those four cases reduce powder capacity a bit. Those I formed from Starline .308 Match brass held 43.4 grains of water, about 2.0 grains less than cases formed from Remington .308 BR brass.

Chamber neck diameter for the Towle pistol is .311 inch. Cartridge neck diameter with a .284-inch bullet seated is .310 inch for a case formed from BR brass and .319 inch for a case formed from Starline .308 Match brass. Case necks have to be reamed or preferably out-side turned to a smaller diameter. I chose the latter and eventually settled on a cartridge neck diameter of .306 inch. The necks of cases formed from BR brass did not require annealing prior to loading, but those formed from other cases have to be annealed.

During my original load development for the 7mm TNT, I was mainly interested in minute-of-angle accuracy, tolerable recoil and enough down-range punch to reliably topple all steel targets. I could not have cared less about maximum velocities possible from the case. Consequently, all the loads I tried were probably several grains of powder shy of developing maximum chamber pressures and cases lasted just short of forever. One batch was still going strong after 15 firings, and during that time they were trimmed and annealed twice.

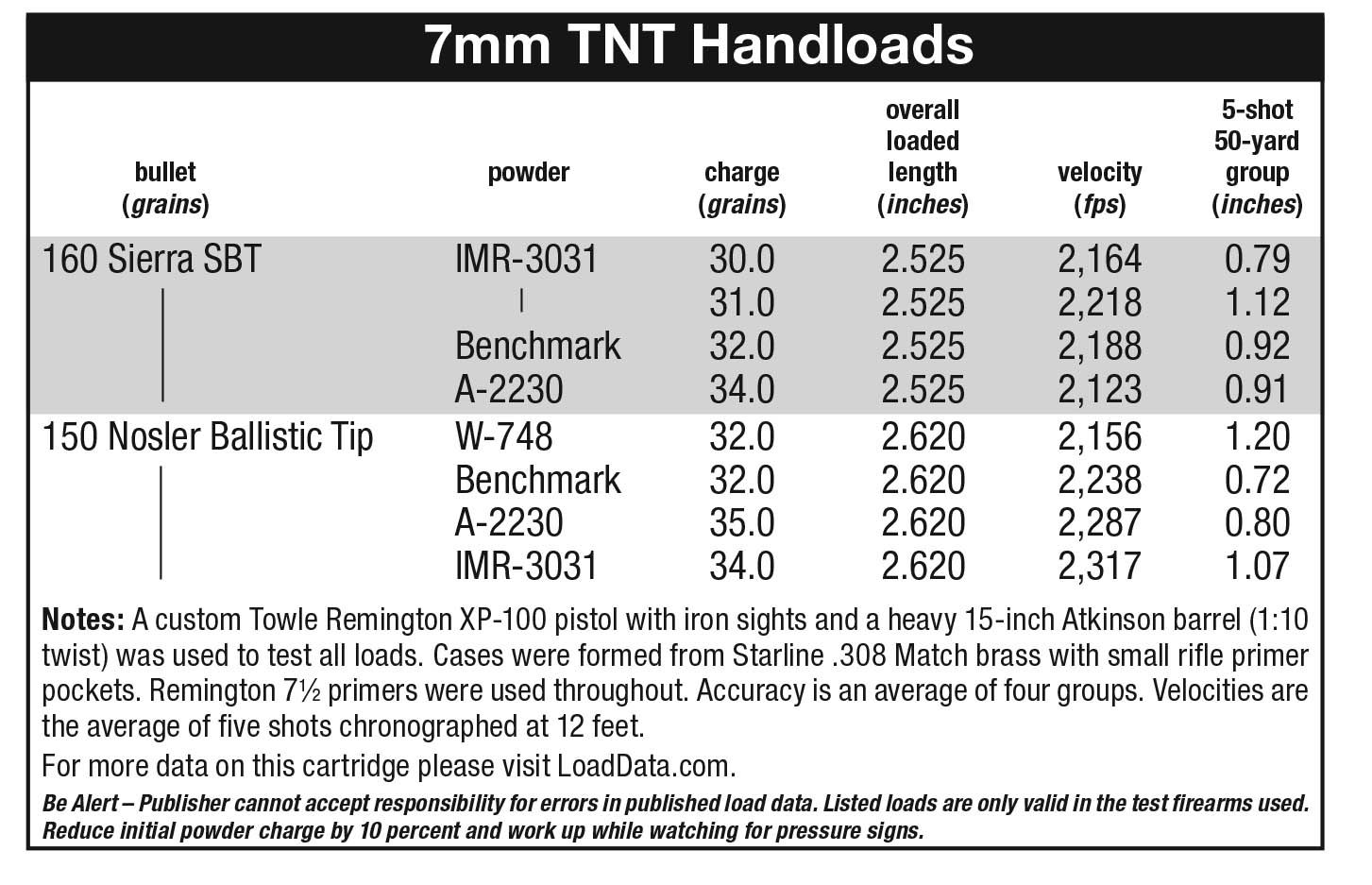

John Towle was an avid metallic silhouette shooter and his favorite load for the 7mm TNT was 30.0 grains of IMR-3031 behind the Sierra 160-grain bullet. That powder worked so well I seldom tried anything else, but its downside is variation in charge weight when thrown with a powder measure. For that reason, if I were shooting the 7mm TNT in competition today, Hodgdon’s Benchmark and Accurate 2230 would receive serious consideration.

Like Goldilocks might have said if she had been a handgun metallic silhouette shooter, the 7mm-08 is too hot, the 7mm BR is too cold and the 7mm TNT is just right.