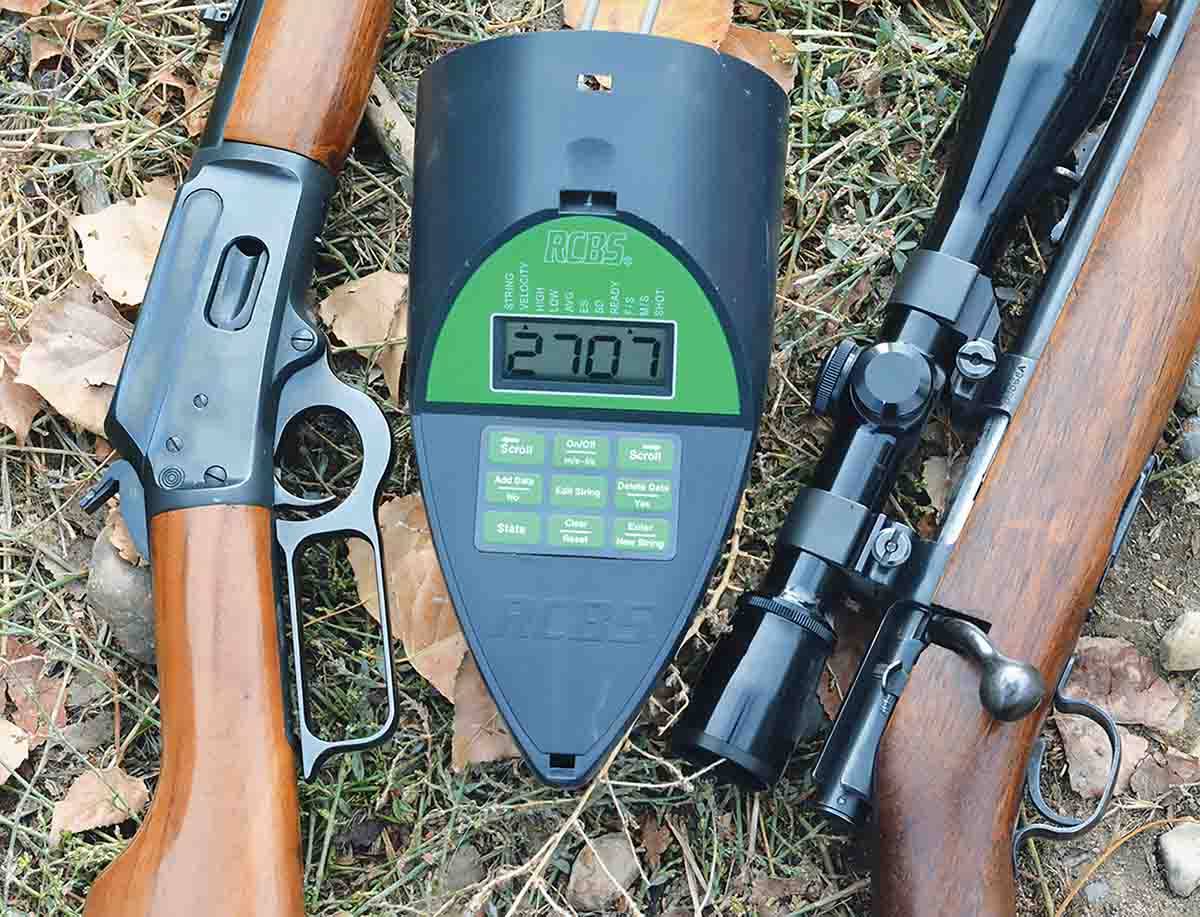

While a Winchester Model 43 rifle (right) was the primary test rifle used to develop .218 Bee “Pet Loads” data, a Marlin Model 1894CL (left) was used to cross-reference select loads and to check for proper function.

Nearly 40 years ago, I made my way off the ranch and down to Idaho’s Treasure Valley to attend a gun show. There, I bumped into a dealer friend who had a splendid Winchester Model 1892 that had been professionally rebarreled to .218 Bee. It also featured a custom high-figure walnut stock that had been fitted with a tang sight and the trigger stoned for a light, crisp pull. It was obviously a high-quality custom rifle that had been owned by a savvy shooter, so we struck a deal and he threw in a supply of brass, bullets and dies. Arriving back at the ranch after dark, select sample handloads were assembled long after bedtime and ready for testing the next morning. At first light, the initial batch of handloads fired struck 1-inch high at 100 yards and grouped into around 1 inch.

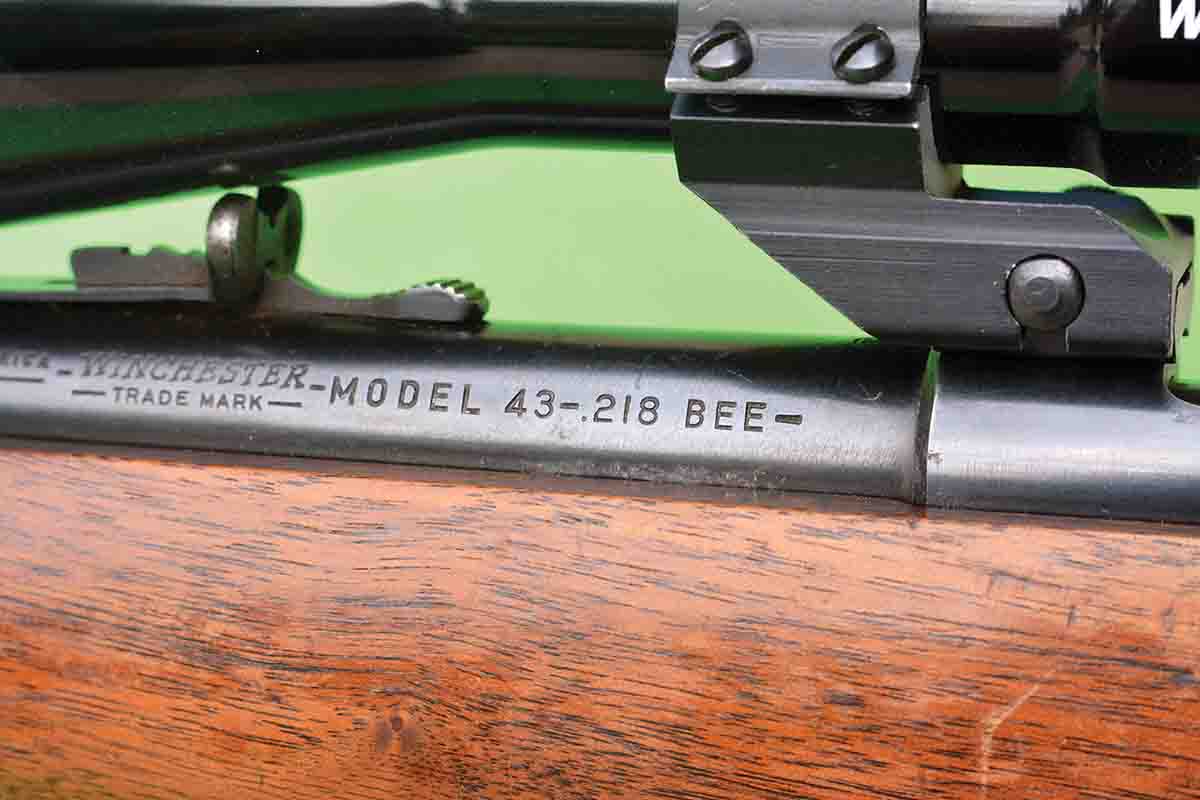

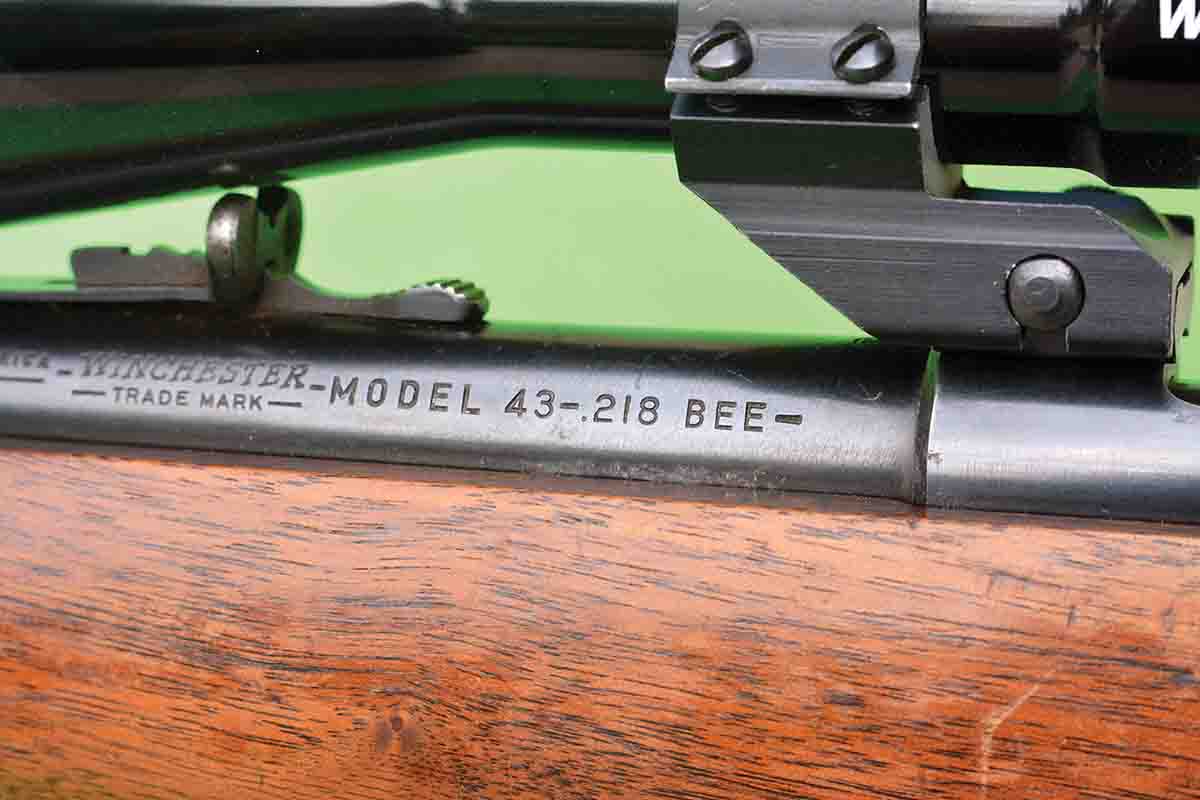

Brian used a Winchester Model 43 to develop handload data for the .218 Bee.

At the time, we were overrun with rockchucks and other pests, and while I owned several good scope-sighted bolt-action rifles chambered in .223 Remington and .22-250 Remington, by comparison, they were bulky, large and often inconvenient to carry on horse or while performing ranch work. I put the lightweight, compact Winchester to good use as a saddle rifle. It was almost too much fun, as rockchucks and other pests inside 200 yards could be hit with high reliability, but many were taken at distances out to around 250 yards. Accuracy and terminal performance left little to be desired, while the virtues of the compact, lightweight Winchester lever action were greatly appreciated. Over the years, I have owned and shot many .218 Bee rifles. It is a better cartridge than is commonly believed and can offer good accuracy and a performance edge over the popular .22 Hornet.

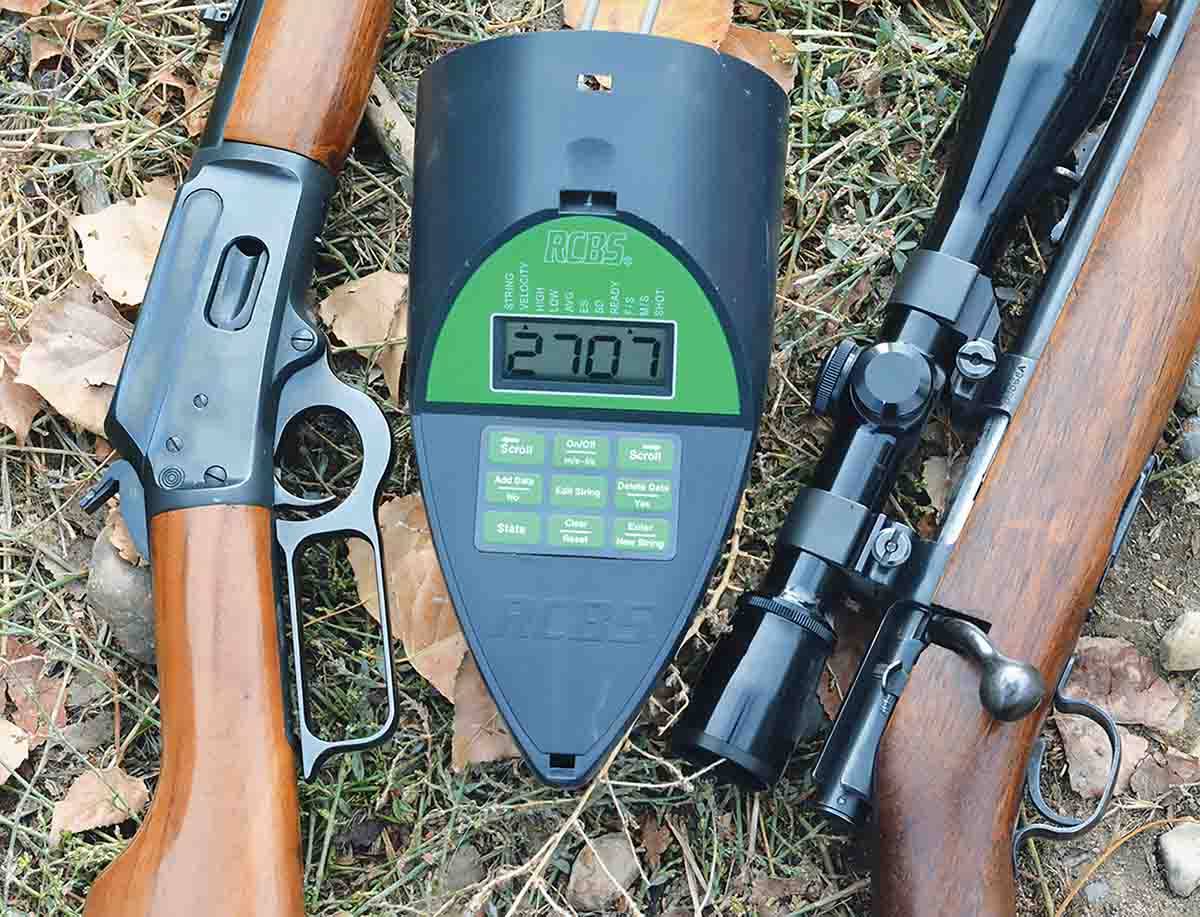

The .218 Bee factory ammunition and handloads were checked for velocity.

The .218 was formally announced in 1938, with reports that a few Model 92 rifles were so chambered. However, it was formally launched in the Winchester Model 65 lever-action rifle that was a modernized Model 1892 influenced by Townsend Whelen. Its name came from its bore size, rather than the more traditional groove size. It would appear that based on the huge popularity of the .25-20 Winchester as an early varmint cartridge that was commonly chambered in Winchester and Marlin lever actions, Winchester was trying to improve upon and modernize that concept. However, 1938 was during the dark days of The Great Depression and sales were sluggish. Although dedicated levergun shooters considered it a great varmint cartridge, trends were clearly towards bolt-action rifles, resulting in the Model 65 discontinuance in 1947. But to better put the .218 and the Model 65 rifle in perspective, just three years after it was introduced, ammunition production was temporarily discontinued, and in 1941, due to the outbreak of World War II, rifle production virtually ceased. Then, just two years after the war, the rifle was formally discontinued. In essence, it hardly had a chance at being a commercial success.

Beginning in 1949, Winchester launched the Model 43 bolt-action rifle that was chambered in .218 (as well as the .22 Hornet, .25-20 and .32-20). Sales were much better; but modern shooters wanted greater range from varmint cartridges and trends were toward modern bolt rifles such as the instantly popular .222 Remington that was introduced in 1950 along with the Remington Model 722 bolt rifle. Both were excellent and modern in every respect and found widespread appeal. The deuce boasted of being rimless, headspaces off the shoulder and had a notable ballistic and accuracy advantage. This resulted in the Model 43, along with the .218 being discontinued in 1957.

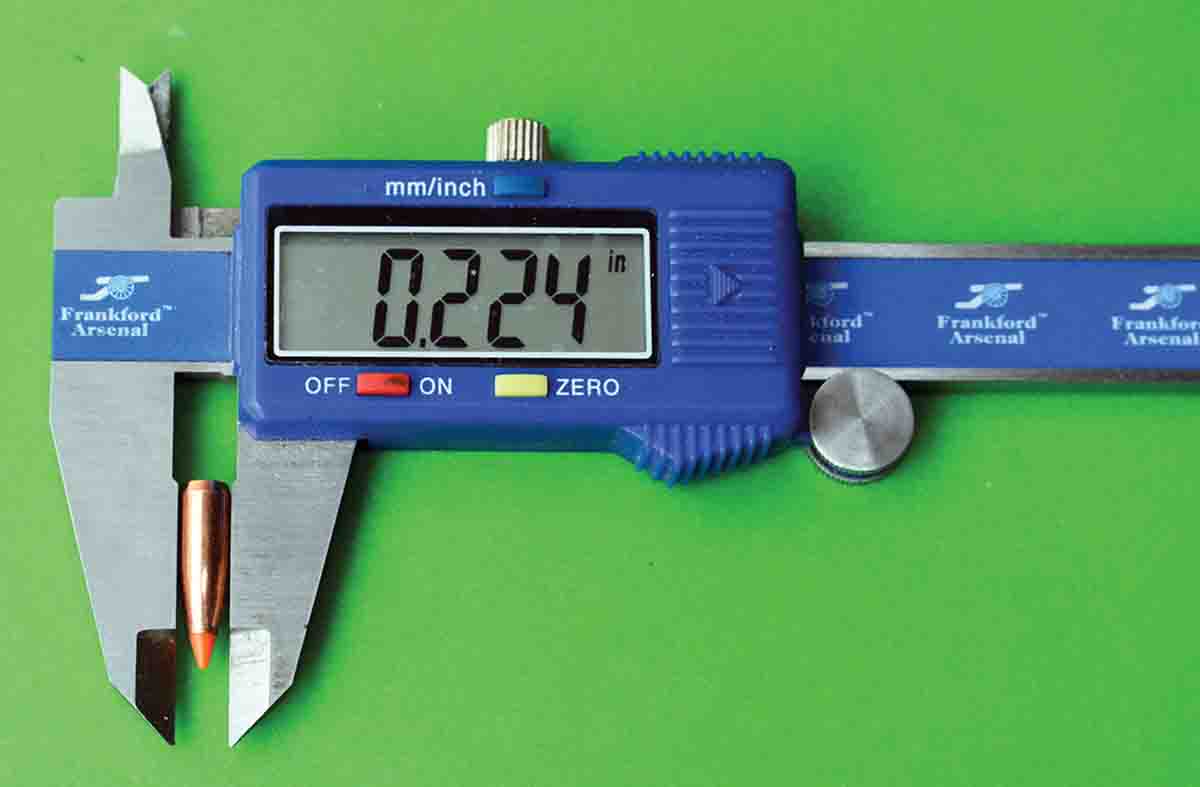

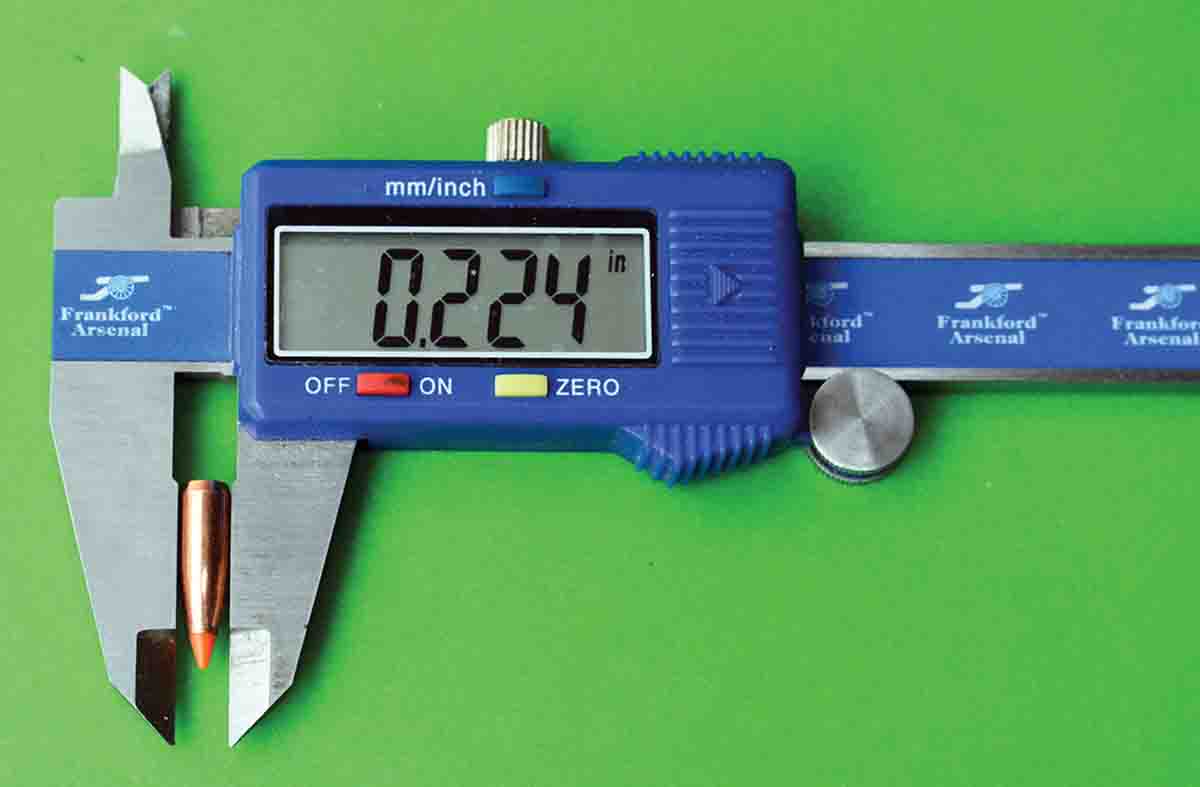

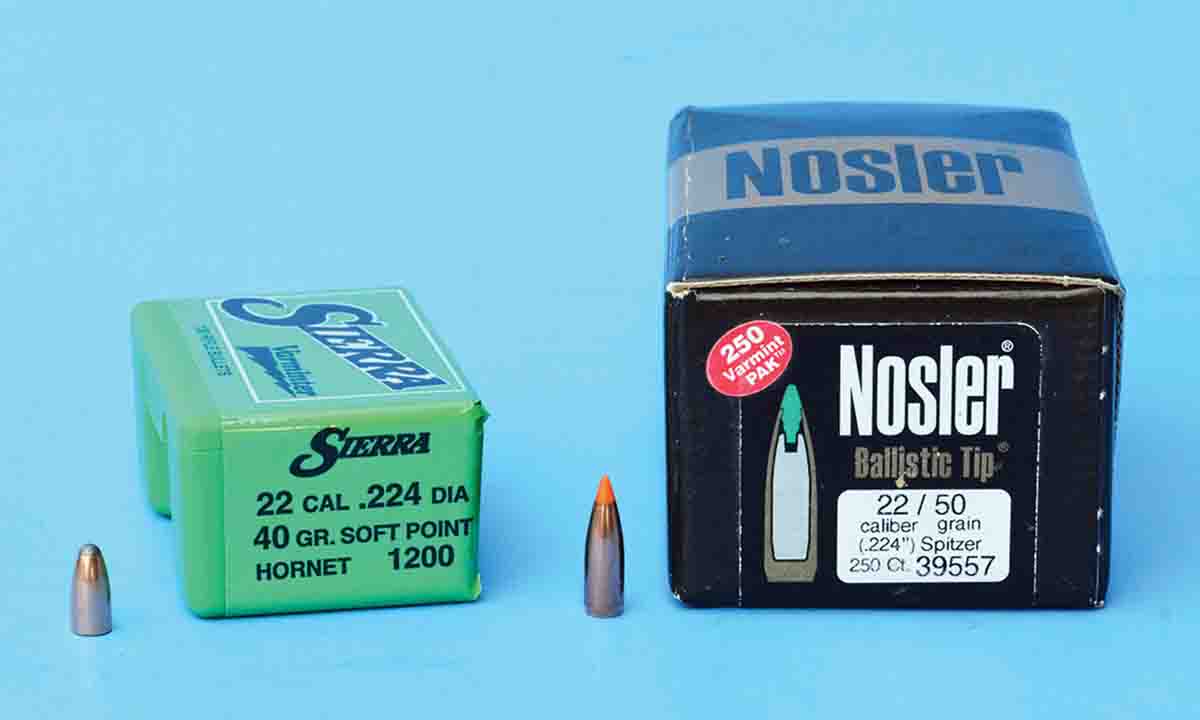

Standard bullet diameter for the .218 Bee is .224 inch.

In subsequent years, Marlin offered the Model 1894CL chambered in .218, Ruger with the No. 1, Browning Arms imported a reproduction Model 65 lever action produced in Japan by Miroku, Thompson Center Arms offered rifles and handguns, Kimber of Oregon produced its Model 82, Sako the L-46 and several other makers have offered rifles as well.

The parent case for the .218 is the .32-20 Winchester, but the former features a slightly longer length and a greater shoulder angle that is set at 15-degrees. While the ballistics of the .218 changed from time-to-time, period loads listed a 46-grain hollowpoint bullet with a muzzle velocity of 2,860 feet per second (fps). Naturally, the bullets nose (or meplat) is flat or blunt enough to prevent primers from setting off when cartridges are loaded into tubular magazines (which we will discuss further in a moment). Originally, the .218 was loaded to higher pressures than it is today, with current industry specifications listing a maximum average pressure of 40,000 CUP.

Maximum overall cartridge length for the .218 Bee is 1.680 inches. However, some rifles will allow a longer cartridge length.

Some sources list pre-World War II .218 ammunition with a maximum average pressure of up to 48,000 psi, but period factory loads were independently tested at around 44,000 psi. This was still too much pressure, as cases were known to separate just forward of the head on the first firing, stick in the chamber, etc. To help alleviate this problem, around 1950, Winchester thickened the case, especially just forward of the head. However, this change reduced case capacity by at least seven percent! As a result, many old published handloads using IMR-4198, IMR-4227 and Alliant (formerly Hercules) 2400 powders will not even fit into newer cases, and those that do, produce far excessive pressures and should never be used. Today’s data is for modern cases produced by Hornady and Winchester and are held to 40,000 CUP pressures.

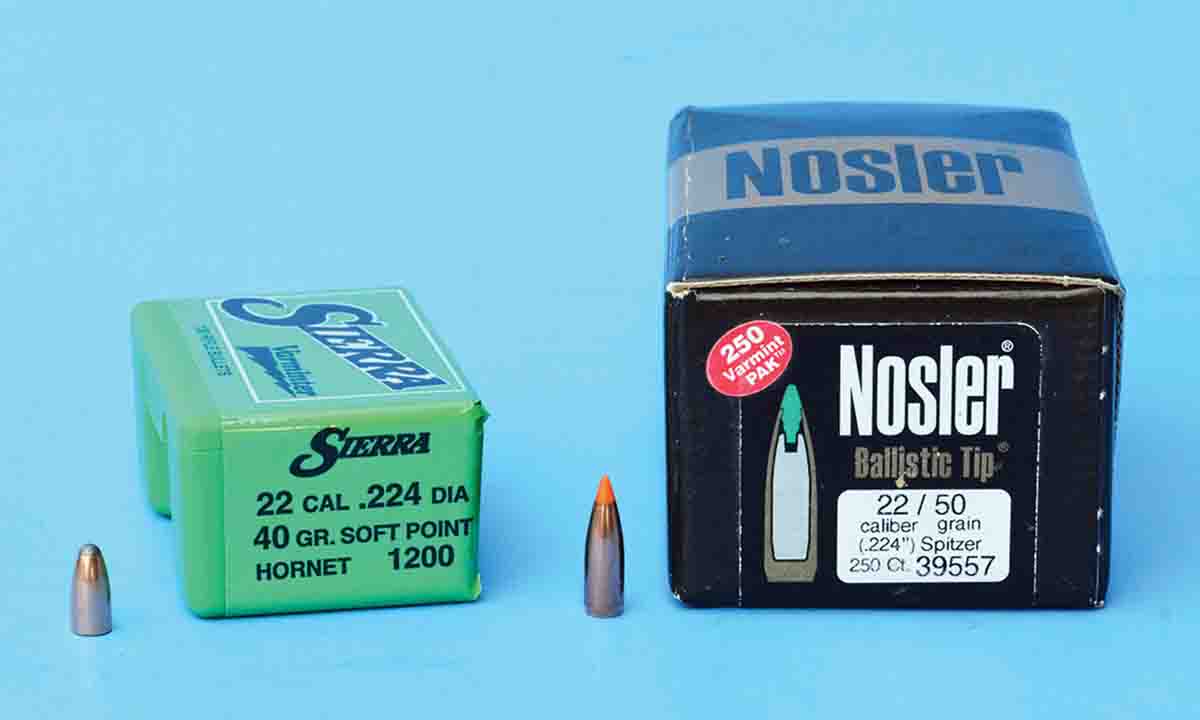

Bullets with a flat point are necessary when loading for .218 Bee rifles that feature a tubular magazine.

For reference, factory-fresh Hornady Custom .218 factory loads containing 45-grain hollowpoint bullets were checked for velocity and accuracy in two test rifles that included a Winchester Model 43 with a 24-inch barrel and a Marlin Model 1894CL with a 22-inch barrel. This load is listed to produce 2,750 fps from a 24-inch barrel, but actually clocked from the above rifles at 2,705 fps and 2,674 fps respectively. Five-shot groups at 100 yards averaged slightly over .80 inch from the scope-sighted Winchester and around 1.50 inches from the aperture-sighted Marlin. Sample Winchester factory loads were not available at press time; rather ammunition that is 20 years old was referenced. These contained the traditional 46-grain hollowpoint bullet that reached 2,758 fps from the Winchester and 2,792 fps from the Marlin. Internal ballistics is always interesting, as the Marlin with a 2-inch shorter barrel produced higher velocities than the Winchester rifle, but I digress. The Winchester grouped these loads into around 1 inch, while the Marlin produced groups that consistently hovered around 1 inch.

In spite of Winchester increasing the .218’s case thickness over 70 years ago, it is still rather thin and requires some finesse during the handloading process. This is not to say that it is difficult to handload, rather, certain steps should be applied gently. For example, if a roll crimp is applied (which is strongly recommended for both bolt-action and lever-action rifles), cases should be of the same length and the crimp applied gently after the bullet is seated to the correct overall cartridge length, but we are getting ahead of ourselves.

The .218 Bee (right) is based on the .32-20 (left) and .25-20 Winchester (center) case, but is slightly longer, features a different shoulder position and is thicker to withstand higher pressures.

The .218 headspaces on the rim, so full-length case sizing is strongly recommended to assure that reloaded cases chamber with ease. Space will not allow the technical reasons why, but the Bee tends to stretch cases. Suffice to say that it is a combination of its overall design that includes a case shoulder that does not contact the corresponding chamber “shoulder” until it is fired, a thin case that is tapered and that it is often fired in lever actions featuring rear locking lugs. Using loads that are slightly below maximum will help reduce stretching and extend case life, and when sizing cases, be certain to lube the inside of case necks, preferably with graphite, to help reduce stretching as the expander ball is pulled back through the case neck.

Alliant 2400 powder easily duplicated factory load performance and was accurate.

The standard primer for the .218 is small rifle, with a CCI BR-4 primer used to develop the accompanying “Pet Loads” data. However, select loads using easy to ignite powders can benefit from the use of small pistol and small pistol magnum primers that serve to reduce extreme spreads and can potentially increase accuracy. Keep in mind that powder charge weights are relatively small (typically between 10 and 15 grains) and will readily ignite with the compound energy associated with small pistol primers. However, there are a couple of potential problems. Pistol primers are shorter than rifle primers, and when seated so that the anvil seats positively to the bottom of the primer pocket, they will seat .005 to .010 inch below flush, which might cause misfires in some rifles. While most small pistol primers offer enough strength to handle the 40,000 CUP pressure associated with the .218, some may not and can potentially rupture. For these reasons the above mentioned CCI BR-4 was selected, which were seated .003 to .005 inch below flush.

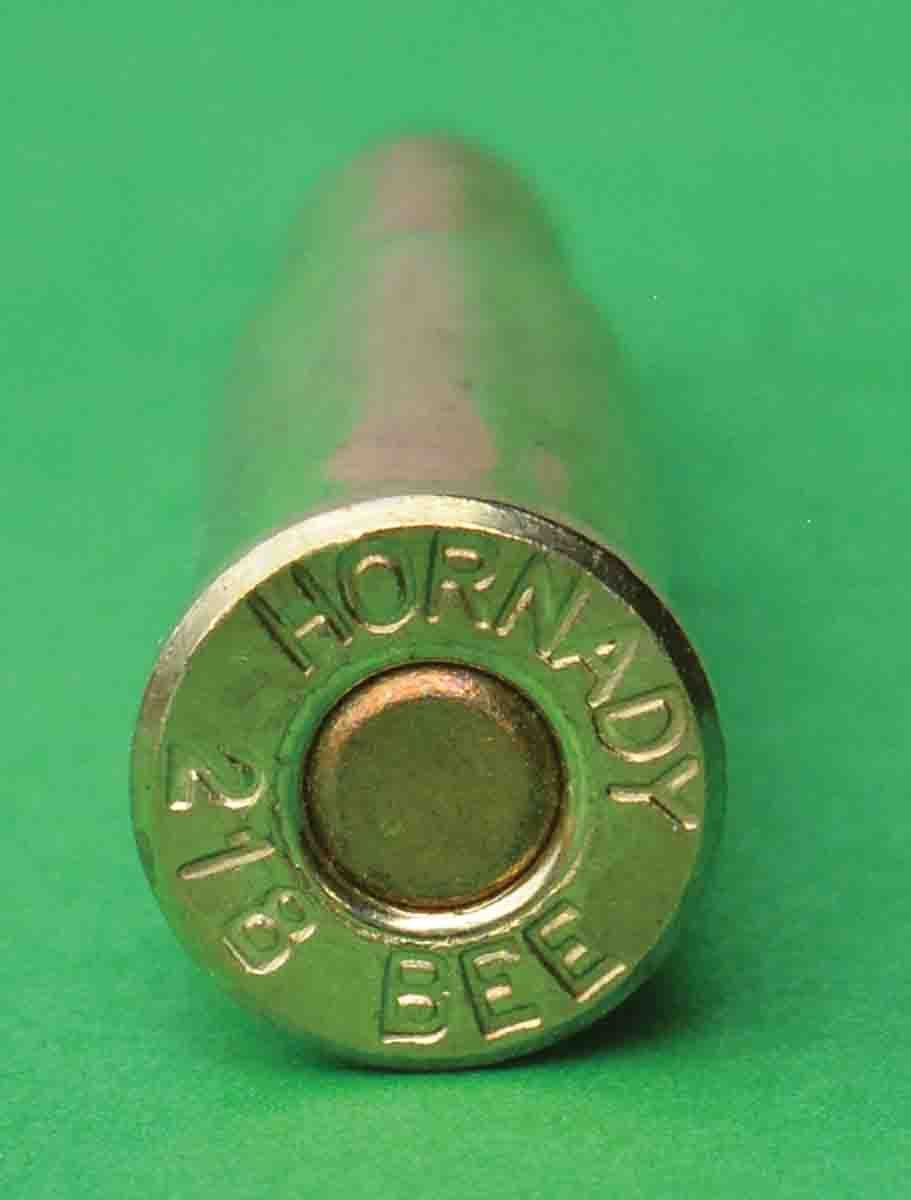

“HORNADY .218 BEE” headstamp.

The standard barrel twist rate for the .218 is 1:16 inches. This twist works perfectly for 35-, 40-, 45- and 46-grain bullet weights that are typically pushed to around 2,800 to 3,100 fps. While I was able to get respectable accuracy at 100 yards from 50- and 53-grain weight spitzer bullets, initial testing at further distances indicated that they may not be properly stabilized. In my experience, the 45- and 46-grain weight bullets are still a great blend of velocity and bullet weight, although select loads with 35- and 40-grain spitzer bullets offer excellent performance in bolt-action rifles.

For those that shoot bolt-action or single-shot rifles, spitzer profile bullets offer a higher ballistic coefficient to help extend effective range. As a reminder, these bullets should never be used in lever-action rifles with tubular magazines. The 35-grain Hornady V-MAX and the 40-grain Nosler Ballistic Tip each gave good accuracy and can be pushed to over 3,000 fps. While Sporting Arms and Ammunition Manufacturers’ Institute (SAAMI) specifications list maximum overall cartridge length at 1.680 inches, when handloading for select bolt-action and single-shot rifles, bullets can be seated out to longer overall lengths. Sometimes, but not always, this can result in improved accuracy. Regardless, experimenting will usually help handloaders tailor loads to maximize performance for a given rifle. With the exception of the 53-grain Hornady V-MAX bullet, all bullets were seated within the SAAMI overall cartridge length specifications.

The .218 Bee (center) offers a performance the modern .223 Remington (right) easily outperforms it.

For use in all rifles, especially lever actions with tubular magazines, bullets featuring a flat point should be selected to prevent possible cartridge detonation in the magazine tube. Currently, Hornady offers its 45-grain Bee HP with a flat point and Speer offers a 46-grain FNSP, again, designed specifically for the .218. Both worked splendidly in the Winchester Model 43 and the Marlin Model 1894CL rifles.

When developing handload data in bolt-action rifles (rather than lever-action rifles) spitzer and semi-spitzer bullets can be used in the .218 Bee.

While crimping bullets is not necessary when they are used in bolt-action and single-shot rifles, a crimp is necessary when loading for lever-action rifles. Nonetheless, a crimp was applied to all handloads, which was applied using a Lee Factory Crimp die. This worked especially well when loading spitzer bullets that are void of a crimp cannelure.

There is a broad selection of suitable powders for handloading the .218. The proper burn rate usually falls roughly between Alliant 2400 and Hodgdon H-4198. Both extruded and spherical powders work very well. However, if powder charges are to be thrown, spherical powders such as Hodgdon H-110, Accurate No. 9, 1680, or fine granule extruded versions such as Alliant 2400 will be preferred. The .218 has a very small powder capacity and even small variances in powder charge weights will translate into higher extreme spreads than is desirable. A top-notch powder measure will play an important role in producing quality ammunition. The Redding Comp 10X Pistol powder measure is designed to precisely throw powder charges that range from 1 to 25 grains and was a valuable tool in preparing ammunition herein.

Brian used RCBS dies and CCI BR-4 primers to develop “Pet Loads” data for the .218 Bee.

Alliant 2400 powder proved to be very consistent and accurate with several bullets, however, when getting close to maximum charge weights, pressures can raise quickly, so caution should be exercised. Another notable powder included Hodgdon H-110 (which is the exact same powder as Winchester 296 and data can be fully interchanged). It easily duplicated factory load performance and produced a rather predictable pressure curve as loads approached maximum. I especially appreciate the above two powders, as they can be thrown with accuracy. Traditionally popular extruded powders for the .218 include IMR-4227, IMR-4198, Hodgdon H-4198 and Alliant Reloder 7; however, to take full advantage of their performance it is generally best to weigh each charge. A modern extruded powder that gave notable performance included Vihtavuori N-120 that was very consistent, accurate and offered higher velocities than factory loads.

Winchester and Hornady offer .218 Bee factory loads.

The Bee, as it is affectionately known, offers efficiency, accuracy and a performance level that is useful for considerable varmint work. It has been chambered for some interesting rifles, but it seems most useful and appealing to this shooter when it is chambered in handy leveraction rifles. Good handloads offer low extreme spreads that often fall below 20 fps and sometimes less than 10 fps, while a good rifle will be capable of sub ¾-inch groups and sometimes below ½-inch. My rifles are not going anywhere, so you will need to find your own!

Brian used a Winchester Model 43 chambered in .218 Bee to develop “Pet Loads” data.

Modern and traditional powders offer excellent performance in the .218 Bee.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)